At the age of sixteen, Joan believed she was called for a divine mission and embarked on a journey from her French hometown of Domremy to Vaucouleurs in May 1428. Her sole purpose was to fulfill the divine mission for which she was anointed. Joan said that she heard, saw, and touched three godly voices every day. These voices were Saints Catherine and Margaret, and the archangel Michael.1 She would have an encounter with these voices in the woods and also when she was in church. These spirits would come to Joan when the church bells in her village would ring, and when they ceased their tolling, she found herself unable to hear the divine voices and would then approach the church warden, and request a more frequent ringing of the bells. The godly whispers given to Joan were instructions to rescue France from the clutches of its English enemies, and in turn, Dauphin Charles would be made France’s rightful king. After these instructions were given to her, the life she once knew would cease to exist. Joan pledged her life to this mission and cut her hair short like that of a man. Joan began to train and dress like a knight, and her training evolved from donning armor to mastering the skills of horseback riding and swordsmanship. Before embarking on her journey, the godly voices gave Joan a powerful gift of belief within herself to complete this mission.2

Joan arrived in Vaucouleurs and informed the captain of the garrison of her divine mission. She recounted her visions to him. In disbelief, the captain of the garrison turned her away.3 Despite being rejected, Joan returned to Vaucouleurs in January 1429. Joan reaffirmed her mission to the captain of the garrison. Impressed by her determination and unwavering devotion, the captain agreed to grant her passage to Chinon.

She was dressed in men’s clothing and was accompanied by a group of six soldiers when she reached Charles. After eleven days of travel, Joan arrived in February of 1429.4 She went at once to the castle where Charles was staying. But Charles didn’t know whether or not to receive her. He sought counsel but was given conflicting advice. Two days passed before he granted Joan an audience, and he hid himself among his courtiers to test Joan. But she quickly detected him and informed him of her godly mission. She pleaded her case and told Charles that he had been encachié et debouté à tort (unjustly chased) from his kingdom, and that she was sent to help him regain possession of it.5 She told him that she wished to go to battle against the English and that she would have him crowned as King at Reims. Joan’s mission was a sign of unheard wonders, which was greeted by ridicule and suspicion.

Dauphin Charles ordered for Joan to be interrogated by theologians at Poitiers. She would be held there for three weeks where she would be questioned by those theologians who were allied to the cause of Dauphin Charles. This stage of the investigation was meant to lead to a decisive decision. It was there that the churchmen, no longer permitted the luxury of reserving judgment, had to approve or disapprove Joan’s mission.6 Here she endured a series of trials, which would entail ceaseless questioning by these theologians. These trials of questions were unnecessary to her religious way of thinking. They simply were a distraction that kept her from fulfilling what she already knew was God’s true command.5 Joan told the theologians that she could not prove her mission at Poitiers but the godly whispers directed her to go to the city of Orléans. In the report from the theologians at Poitiers, they advised Charles to make use of Joan due to the dire situation of Orléans, which had been under siege for months by the English. From here, she would return to Chinon where Charles furnished Joan with a household of several men, military equipment, and a squire.8 She would also be accompanied by her two brothers Pierre and Jacquemin.

Joan and her army set out for Orléans on April 27, 1429. The city itself had been besieged since October 12, 1428.9 The city was surrounded by a ring of English soldiers. Two days later, Joan and La Hire, a French commander, entered with supplies to aid the troops.10 It was here that Joan was told that battle action would need to be postponed until further reinforcements could be brought in. Joan’s army was significantly outnumbered compared to that of her enemy.

On the night of May 4, Joan suddenly sprang up from her sleep with a spirit of inspiration.11 With this spirit, Joan formulated the idea that she must go and attack the English immediately. Joan then armed herself and scurried to an English fort located east of the city of Orléans .12 She then discovered an engagement that was already in motion at this location. Then she arrived and awoke the French, and in turn overtook the English fort.

On the morning of May 6, Joan crossed to the south bank of the river and advanced toward another fort.13 The English immediately evacuated in order to defend a stronger position that was being attacked nearby. In turn, this gave Joan and La Hire an opportunity to attack the English and take their fort by storm. On the morning of May 7, the French advanced against the fort of Les Tourelles.3 Joan was hit by an arrow during the encounter, but despite this setback, she quickly tended her wounds and returned to the battle. Joan demonstrated bravery like no other.

The French commanders maintained the attack until the English capitulated. Joan’s visions were coming to pass. She was leading the French to victory against the English.11 The English were seen retreating from the battlefield. The victory took place on a Sunday and Joan refused to allow any further pursuit.

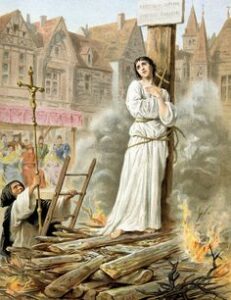

Later that month, Dauphin Charles would be crowned King Charles VII of France. Joan of Arc knelt at his feet in gratitude for the opportunity given to her. Joan was later captured in May 1430 and sold to the English, who tried her for heresy.3 During Joan’s trial, she was accused of having the ability to communicate with saints, which they claimed was a power sourced by the devil.17 Due to her wearing men’s clothing, Joan’s judges accused her of being a whore and blamed her for the loss of bravery in their English troops. Joan’s sexuality was then questioned while on trial. The judges debated over whether or not she was even a woman.17 The maid of Orléans was found guilty of being a witch and a heretic. On May 30, 1431, the French heroine Joan of Arc was burned at the stake at Rouen in France. Even after her death, Joan’s body would be shown to the crowd to partake in the debate of her sexuality. Was she a male or a female?

Joan of Arc was magnetic in many different ways. Her visions led her to dominate a masculine-powered region.19 In this region she served as a general directing troops, outlining military strategies, directing troops, and proposing diplomatic solutions.

- Anne Llewellyn Barstow, “Joan of Arc and Female Mysticism,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 1, no. 2 (1985): 33. ↵

- Anne Llewellyn Barstow, “Joan of Arc and Female Mysticism,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 1, no. 2 (1985): 29-30. ↵

- Yvonne Lanhers and Malcolm G.A. Vale, “Joan of Arc: Biography, Death, Accomplishments, & Facts,” Britannica Online, accessed September 20, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Joan-of-Arc ↵

- Yvonne Lanhers and Malcolm G.A. Vale, “Joan of Arc: Biography, Death, Accomplishments, & Facts,” Britannica Online, accessed September 20, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Joan-of-Arc ↵

- Deborah A Fraioli, Joan of Arc : The Early Debate (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Boydell Press, 2000), 5. ↵

- Deborah A Fraioli, Joan of Arc : The Early Debate (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Boydell Press, 2000), 43. ↵

- Deborah A Fraioli, Joan of Arc : The Early Debate (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Boydell Press, 2000), 5. ↵

- Stewart Paul, “Joan of Arc : A History / Helen Castor.,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, September 1, 2022. ↵

- Yvonne Lanhers and Malcolm G.A. Vale, “Joan of Arc: Biography, Death, Accomplishments, & Facts,” Britannica Online, accessed September 20, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Joan-of-Arc ↵

- Stewart Paul, “Joan of Arc : A History,” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, September 1, 2022. ↵

- Stewart Paul, “Joan of Arc : A History,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, September 1, 2022. ↵

- Yvonne Lanhers and Malcolm G.A. Vale, “Joan of Arc: Biography, Death, Accomplishments, & Facts,” Britannica Online, accessed September 20, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Joan-of-Arc ↵

- Yvonne Lanhers and Malcolm G.A. Vale, “Joan of Arc: Biography, Death, Accomplishments, & Facts,” Britannica Online, accessed September 20, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Joan-of-Arc ↵

- Yvonne Lanhers and Malcolm G.A. Vale, “Joan of Arc: Biography, Death, Accomplishments, & Facts,” Britannica Online, accessed September 20, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Joan-of-Arc ↵

- Stewart Paul, “Joan of Arc : A History,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, September 1, 2022. ↵

- Yvonne Lanhers and Malcolm G.A. Vale, “Joan of Arc: Biography, Death, Accomplishments, & Facts,” Britannica Online, accessed September 20, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Joan-of-Arc ↵

- Anne Llewellyn Barstow, “Joan of Arc and Female Mysticism,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 1, no. 2 (1985): 42. ↵

- Anne Llewellyn Barstow, “Joan of Arc and Female Mysticism,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 1, no. 2 (1985): 42. ↵

- Anne Llewellyn Barstow, “Joan of Arc and Female Mysticism,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 1, no. 2 (1985): 30. ↵