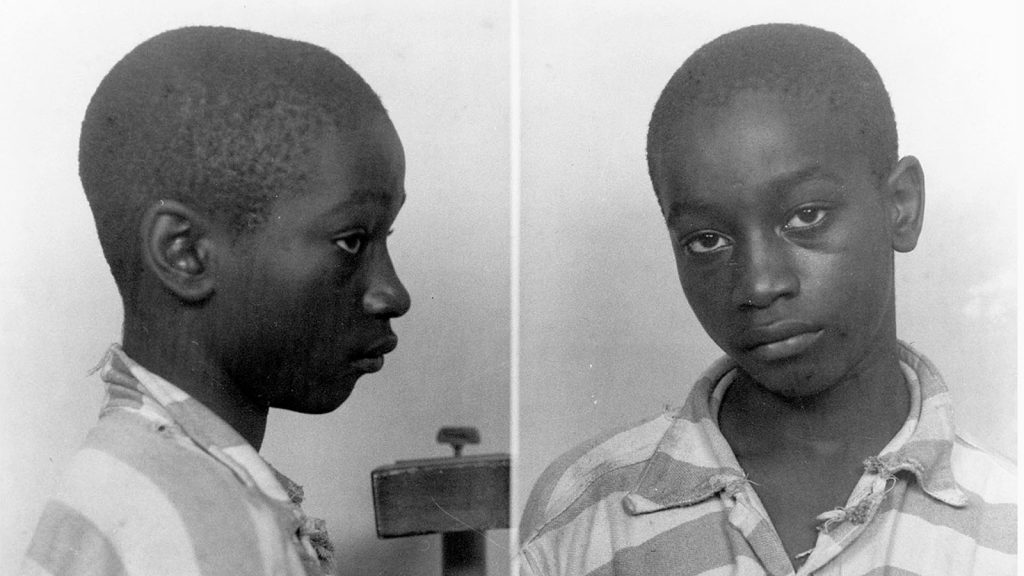

June 16, 1944 was execution day at the Central Correctional Institution in Columbia, and next on the docket to confront the electrical chair was George Stinney, a 14-year-old African American boy from Acolu, South Carolina. George weighed merely 95 pounds and stood at only 5” 1′ at the time he was strapped to an electric chair too big for his physique.1 Due to George’s small physique, extra holes needed to be punched into the chair’s leather bindings before the bindings could fit onto George’s limbs. This extra step bought George a couple extra minutes of life before he faced the electric chair.2 What was 14-year-old George Stinney thinking about right before execution? Surely not that he would soon become the youngest person executed in the 20th century.3

On March 24, 1944, tragedy and injustice came strolling into the small segregated lumber mill town of Alcolu, South Carolina. Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 7, were walking with their bike when they came across Aime Stinney Ruffner and George Stinney. The girls asked Aime and George whether or not they knew where they could find Maypops. Aime and George responded with a “no” and the girls went on their way. The night of March 24, Betty and Mary were reported missing after both girls failed to return home. The morning after, Betty June Binnicker and Mary Emma Thames were found dead in a ditch with their bikes laying on top of them. Police arrived at the Stinney household and arrested George, a 14-year-old African American boy, for the murders on Betty June Binnicker and Mary Emma Thames.4 Unfortunately, at the time police arrested George, the 1966 Supreme Court ruling on Miranda v. Arizona, which requires law enforcement officials to advise suspects of their rights, had not been ruled yet.5 After the police arrested and interrogated George without any access to his parents nor to an attorney, George confessed to the murders of Betty Binnicker and Mary Thame.6 George Stinney was not the only party impacted as a result of the murders, the Stinney family was persecuted by the rest of the town due the accusation against George. George Stinney Sr. was fired from work and the entire family was forced to permanently leave Acolu and move to Pinewood where the grandmother resided. Aime Stinney Ruffner stated, “We had no choice, the crowd came and they said they were going to get us.”7

The judge presiding over the case appointed Charles Plowden, 31-year-old local lawyer and aspiring politician, to represent George Stinney during the trial. On April 24, 1944, residents of Alcolu packed the local courthouse hoping justice would be served swiftly. A jury composed of 12 white men would be destined to determine George Stinney’s fate.8 Plowden failed to motion for a change of venue, which is a motion to change the location of a trial to overcome local prejudice. Stinney could have had a less partial jury in a different location. The prosecution’s case relied on the testimony of two police officers giving an account of Stinney’s confession he made during his interrogation. According to the police, Stinney confessed to having followed Betty Binnicker and Mary Thames after initially making contact with the girls, then unsuccessfully attempted to rape Betty, and then proceeded to beat both Betty and Mary with a railroad spike that had been laying around. The prosecution presented Stinney’s birth certificate as the last piece of evidence. The prosecution presented the birth certificate to make the case that Stinney was born on October 21, 1921, making him 14 years of age, which was traditionally the accepted age of criminal responsibility at the time.9 Plowden failed to cross-examine the prosecution’s witnesses, call forth any witness that could have corroborated with Stinney’s alibi, question the circumstances under which the police obtained the confession, nor to point out the lack of physical evidence, nor to point out the impracticality of a 14-year-old boy weighing 95 pounds and standing at 5 feet and 1 inch of physically being able to murder two girls, and finally failed to file an appeal. Plowden’s only defense comprised of the defendant being too young to be held responsible for the crimes he committed. Stinney’s trial, that would determine whether he lived or died, lasted a total of 3 hours. The judge sentenced the jury to deliberation, and 10 minutes later the jury comprised of 12 white men, found 14 year old George Stinney guilty of the murders of Betty June Binnicker and Mary Emma Thames. The judge sentenced George Stinney to death by electrocution. On June 16, 1944, the 2,400 volts of electricity passing through George Stinney rendered his body lifeless.10

70 years after the execution of George Stinney, Stinney’s three remaining siblings are seeking justice of their own with the help of a group of lawyers and civil rights advocates determined to exonerate Stinney. Stinney’s prosecution combined unconstitutional errors with serious misconduct. The team of attorneys argued in the Sumter County Courthouse that Stinney’s verdict was solely based on a coerced confession, therefore, the verdict should be thrown out.11 Due to new testimony, Stinney’s family, along with the team of attorneys, are hoping Judge Carmen T. Mullen, of the Fourteenth Circuit Court in South Carolina, rules in their favor. Despite most of the evidence, including Stinney’s confession and the transcript of the trial disappeared, Mullen heard new testimony from Stinney’s brothers and sisters, a witness from the search party, a child forensic psychiatrist, and a statement from Wilford Hunter, Stinney’s former cellmate.12 Frankie Bailey Dyches, the niece of one of the victims, stated, “He (George Stinney) was tried, found guilty by the laws of 1944, which are completely different now—it can’t be compared— and I think that it needs to be left as is.”13 Circuit Judge Carmen Mullen makes an important distinction in the Stinney case by stating that her task is not deciding whether Stinney is guilty or innocent, but rather to decide whether or not Stinney received a fair trial. On December 10, 2014, Circuit Judge Carmen Mullen vacated George Stinney’s conviction. Mullen ruled that Stinney’s confession was likely coerced and therefore inadmissible, “due to the power differential between his position as a 14-year-old black male apprehended and questioned by white, uniformed law enforcement in a small, segregated mill town in South Carolina.”14

George Stinney was tried, convicted of murdering two young White girls, and sentenced to death by electrocution, all in a single afternoon. The story of George Stinney showcases the irreversible actions that occur in a flawed criminal justice system that implements the death penalty primarily against minorities. The court system failed to provide George Stinney with a fair and impartial trial in 1944. As a result, George Stinney paid the ultimate price, death. 70 years after the death of Stinney, the Fourteenth Circuit Court in South Carolina ruled justly by vacating Stinney’s conviction. That moment on June 16, 1944 when 2,400 volts of electricity passed through Stinney’s body, it rendered him lifeless. The death of George Stinney sealed his fate in history as the youngest person executed in the 20th century. The finality of the death penalty by definition continues to risk the loss of innocents’ lives.

Warning: the video linked below is a very realistic, violent, and disturbing set of images of what the suffering and execution must have felt to young George Stinney Jr.

- Elaine Aradillas, Jill Smolowe, Howard Breuer, Michelle Boudin, “A Family’s Quest for Justice Wrongfully Executed,”(People, March, 2014), 73. ↵

- Charles Kelly, “Next Stop, Eternity,” (Life Rich Publishing, April 27, 2016), …. ↵

- Jesse Wegman, “A Boy’s Execution, 70 Years Later,” (New York: New York Times, June, 2014), 8. ↵

- Elaine Aradillas, Jill Smolowe, Howard Breuer, Michelle Boudin, “A Family’s Quest for Justice Wrongfully Executed,”(People, March, 2014), 75. ↵

- Miranda v. Arizona, 384 US 436 (1966). ↵

- Elaine Aradillas, Jill Smolowe, Howard Breuer, Michelle Boudin, “A Family’s Quest for Justice Wrongfully Executed,”(People, March, 2014), 75. ↵

- Elaine Aradillas, Jill Smolowe, Howard Breuer, Michelle Boudin, “A Family’s Quest for Justice Wrongfully Executed,”(People, March, 2014), 74. ↵

- Mark Kantrowitz, “The Killing of George Stinney Jr.,”(Rhode Island: Rhode Island Lawyers Weekly, 2018). ↵

- David Bruck, “Executing Teen Killers Again,” (The Washington Post, September 15, 1985). ↵

- Mark Kantrowitz, “The Killing of George Stinney Jr.,”(Rhode Island: Rhode Island Lawyers Weekly, 2018). ↵

- Jesse Wegman, “George Stinney was Executed at 14,” (New York: New York Times, January 12, 2015), 9. ↵

- Lindsey Beaver, “It took 10 minutes to convict 14-year-old George Stinney Jr. It took 70 years after his execution to exonerate him,” (The Washington Post, December 18, 2014). ↵

- Jesse Wegman, “George Stinney was Executed at 14,” (New York: New York Times, January 12, 2015), 8. ↵

- Brad Knickerbocker, “Executed at Age 14, George Stinney Exonerated 70 Years Later,”(Christian Science Monitor, December, 2014). ↵

97 comments

Amanda Uribe

It truly is sad that an innocent boy was executed for something he didn’t do. I had never even heard about this case. This really does show the injustice in our court systems and our racial prejudice. It was heartbreaking to think about a 14 year old boy getting the death penalty. The court system really failed George. I hope more people learn his story and are able to educate others on this story.

Gabriel Lopez

That’s horrible how they gave him that harsh of a punishment when he’s that young, let alone accusing him of something he didn’t do. It just shows how bad discrimination was back then, and on top of that, he most likely confessed to the murders of the two girls out of pressure. I can’t imagine what his family had to mourn through until they were finally able to speak up 70 years later.

Nicole Ortiz

I had known before about this story but it was not one that was commonly talked about. When i was reading this article, all i could think about was the case of the Central Park Five, in which 5 young black boys were accused of raping a women and who were also coerced into confessing to a crime they didn’t commit in hopes of being able to be set free. Watching the video that’s included in this article just frustrated me even more because there are so many people being accused of crimes that they never committed but sadly, racism still exists and is used as a justification for those accusations.

Nicholas Robitille

This is truly a blight on American History. It truly goes to show just how bad court system practices and how bad racial prejudices were back then. I realize that this is one of many alike injustices commited in these times, but I hope it is one of the last injustices that are commited on this scale. May we never have a time as trying and turbulent.

Lilia Seijas

This is not a story commonly known by most people. However, it is definitely not uncommon for young teenagers to be sentenced for crimes they did not commit. I found this case to be similar to the central park five cases in New York City. Although they were not sentenced to death, they did spend plenty of their lives in jail for a crime they did not commit. This article shines a great light on how easily our justice system can be bias and unjust to many and does not take into consideration all of the factors in every case.

Amanda Quiroz

That is so wrong. I hate thinking about the fact that people could be (and still can be) so ignorant as to put a fourteen year old black boy in front of a jury that looks down on minorities. It didn’t just impact him. It impacted his family. They had to leave because people were going to run them out. That’s just sad.

Isabella Torres

It is absurd how George Stinney Jr.’s prosecution was so unconstitutional and so full of blatant errors, especially because he was only fourteen years old. Although it wasn’t known for sure whether or not he was innocent, it is absolutely horrible how segregation, racism, and lack of a fair and impartial trial affected Stinney in the end. Personally, I do not agree with the implementation of the death penalty, and the fact that it was used in tis case with such little evidence makes me sick to my stomach. This article was very well done and gave a lot of interesting information that I wasn’t aware of before.

Shea Slusser

I realize laws of that time period were very unjustified and wrong due to the discrimination of the United States. Before knowing of the final verdict in this case, the fact that a 14 year old black boy was being tried by 12 white men in a society who strongly looks down upon minorities, is in its unlawful. George should have been given a more time before the trial and the final verdict of electrification. Its sicking to think this nation, not even a century ago, put a 14 year old boy in a electric chair. We should be thankful for the rights we have today, because we obviously were not in the right mind set during this time.

Carly Jimenez

I believe a story like this deserves to be told. It is so unfortunate that these sort of things happen to completely innocent people especially a child who was forced into saying something that he did not do. The fact that there were 12 white men as the jurors meant that no matter what was said they were going to say that George was guilty, and so they did. Racism in those days was at it’s highest and to see that they had no evidence that it was him that did it is just unjust. It is upsetting to see that it took 70 years to find out that boy was not guilty when it should have been back in 1944. This was a great Article I really enjoyed reading it. Great work.

Sebastian Portilla

This makes me feel sick. How ignorant and insensible people were back then. Its extremely sad for the ones who lost their lives at this time and for People who continue to lose their lives to this day. George shouldn’t have the rights that everyone is given and law enforcement shouldn’t have been so intimidating to a 14 year old. One day the world will change. We still have careless people in charge but for the mean time we will continue to fight for what’s right.