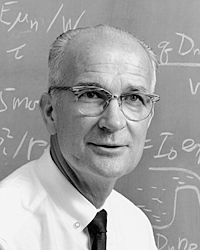

It was March 6, 1900. San Francisco, California was the central hub for racism and discrimination for many Asian individuals. On that fateful day in March, 41-year-old Wing Chung Ging was found dead in the Globe Hotel cellar located in Chinatown.1 Upon inspection of the crime scene, there were no splatters of blood, stab wounds, bullet wounds, or even a single scratch. This killer was not human. Many suspected he died of typhoid or of a sexually transmitted disease. However, when his body was taken to be prepared for a proper resting place, Chinese physicians became worried when there was bacteria detected in the corpse. To be on the safe side, they then decided to bring Ging’s body to a more experienced physician, Wilfred Kellogg, who was starting to find signs of a lethal plague on his own. A panicked Kellogg turned to someone he knew could best help with this alarming concern. Dr. Joseph Kinyoun, one of the men who ran the National Hygienic Laboratory, was transferred to take down this disease that was killing people.2 This man would run trials and would attempt to prove that this plague had arrived to terrorize the citizens of San Francisco. Unfortunately, this would be a task that would not be an easy feat.

Kellogg arrived at Kinyoun’s lab with the swollen lymph nodes that came from the infected body. To determine whether or not this Chinese man carried the dreaded plague, the bacteriologists took the samples and infected a guinea pig, a rat, and a monkey. As their test subjects were slowly being inoculated, Kinyoun and Kellogg alerted the City Board of Health that Bubonic plague may have struck the city of San Francisco. Naturally, this caused panic to erupt among the board members, who soon decided to lock down the Chinatown section of the city.3

While doctors and scientists were trying to figure out how to combat this outbreak, news sources began their input on the matter. Without any knowledge of the disease, in less than 48-hours after the body was found in the cellar, headlines started to appear. The San Francisco Call published an article with the title, “Plague Fake is Part of a Plot Plunder;” the San Francisco Chronicle joined in by arguing that “individuals were so lost to all sense of humanity as for personal ends to bring upon the community the horrors of a plague scare;” and even the Bulletin accused the health board of being desperate for money. There was one individual who attempted to speak up for the board and correct the extreme allegations being thrown around by explaining to one of the newspaper editors that the plague truly existed. However, the man was shut down and called a liar, which allowed journalists to continue their criticism and accusations against the Board of Health.4

The tension between the business corporations and health officials intensified. Soon, only sixty hours after that fateful day, the demand to lift the quarantine increased significantly even though health officials knew this disease would spread rapidly if they were to lift the lockdown. The test subjects back in Kinyoun’s lab were still alive, which only made Kinyoun and Kellogg slowly start to worry, as results were not coming back soon enough. Time was of the essence for these doctors, as they were the ones who could help save the citizens of San Francisco. However, journalists had other plans. Rather than taking time to better understand how serious this disease was, they decided to side with businessmen and stress how this scaremongering would destroy the economy. News outlets continued to downplay the severity of this situation, spewing out headlines titled “Plague Fake Exploded” while arguing how these “lies” were creating “vast injury to business inflicted by unscrupulous treasury raiders.” Other editors simply stated that the plague “wasn’t as severe,” and continued to target the government of San Francisco for being an inconvenience to the police. Newspaper publishers thought it was inconvenient to lock down a whole town, since there was no such thing as the plague entering San Francisco.5

The snarky journalists would soon be proven wrong when the lab results finally came back. On March 12, Kinyoun noticed his animal test subjects were lying lifeless in their cells. Upon discovery, he realized that this was a bacteria known as Yersinia Pestis. This bacterium was known to be the main cause of the bubonic plague of the fourteenth century.6 This bacteria is passed down from a “rat flea,” to a rodent, then to a human. If humans were to come into close proximity with the infected rats, the flea will jump to the new host and spread the germs. The results that came out proved that the plague had made its presence known. In response to this crisis, Mayor Phelan decided to call in about one-hundred physicians to conduct house searches within Chinatown. Around this time, there were about 25,000 Chinese people living within the town.7

One of the volunteers, Dr. William G. Hay, discovered that these people were living in conditions that seemed almost inhabitable. The recruits had to make their way through a maze that contained rat holes. When taking a closer look, they noticed these holes were being connected by passageways that were created underground by the infected rodents. Dr. Hay documented in one of the houses that, “the rascals did not use the closet provided, but instead cut holes in the wooden sewer, and when the sewer was congested from flushing by rain or artificial means, the contents, of course, were discharged into the room, and more nasty yet, under the bunks in which they slept.” This fact alone was a huge reason as to why the disease was spreading throughout Chinatown. If the state of the rooms was not bad enough, the Chinese would also hide their ill and dead relatives around the house in order to avoid autopsies being performed on them. As the recruited physicians made their way around the house, the sick would be escorted from room to room while the dead would be positioned on a table in a way where it seemed as if they were sleeping or playing a game of dominoes.8

The terror of the media did not stop after the lab results came back. Newspapers still denied the fact that the plague made its arrival. Many business owners also started to become stressed out rather than worrying about the public’s health, because they were worried that millions of dollars their companies could be making would be in jeopardy due to these health board officials scaring the city. Later on, on May 16, Kinyoun sent a telegram to Surgeon General Walter Wyman alerting him that this plague had to “now be regarded as epidemic, as no connection can be traced between cases.”9

With the cases of plague increasing, Secretary of the Treasury Lyman J. Gage took time to talk to President William McKinley to ask if he could apply the strict quarantine law of 1890 on Chinatown. Once this law was in place, Asians would not be allowed to leave the state of California unless approved by one of Kinyoun’s recruited officers, in fear of spreading the virus.10 This did not sit well with the head merchants of Chinatown, who were also known as the Chinese Six Companies. However, they were not confident enough to come forward. Instead of keeping silent, one of the secretaries, who was well-known within the infected town, decided to take charge and fight in federal court for this lockdown to be lifted. He stated, “It is wrong to close an extensive section like Chinatown simply upon the suspicion that a man might have died of the plague.”11 The secretary continued to argue that the Marine Hospital Service regulations were not providing legal protection that was equal to Asian individuals. The ultimate decision after this hearing was to only quarantine the regions within Chinatown that had infected cases only; however, there would still be a border around the town that prohibited anyone from coming in or out.12

As the businessmen continued to point fingers at the Board of Health, Kinyoun began to take action alongside the Marine Hospital Service, by creating this experimental vaccine for the infected. They decided to utilize the Haffkine prophylactic vaccine, and attempted to ask the Chinese if they were willing to take the experimental immunization. At a health board meeting, the Chinese Six Companies came to an agreement with Kinyoun and reassured him that everyone in town would take the vaccine without any complications.13 When May 20 rolled around, no one came to the physicians to receive their inoculation. This confused Kinyoun because he was reassured that the townspeople would come.14

What Kinyoun did not know was that different physicians came to the town to warn the people that if they took the experimental serum, they would die. These physicians told the townspeople that they knew there would be negative effects, and with that, there were protests against the serum outside of the Chinese Six Companies building. The head merchants tried reassuring the protestors that there was nothing to fear, and to allow the physicians to inject the serum. The people cried out for the merchants to be the first to take the vaccination; however, they refused almost immediately. When Kinyoun and his team arrived to administer the vaccine, there was no one in sight who was willing to take the experimental immunization.13 To make matters worse, a rumor published by the western press went around that hitmen were being ordered to threaten people who attempted to promote or receive the dosage of serum. 16

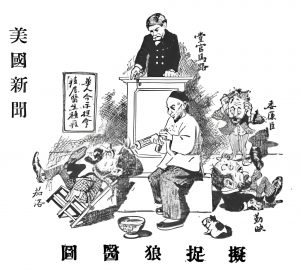

Kinyoun’s job did not get any easier as he continued to receive harsh slander and hatred due to being the head officer of this catastrophic event. The Chinese daily newspaper decided to put out a political cartoon that showed Kinyoun being injected in the head with the vaccine while the judge looked down at him with an approving look. Despite these newspaper articles, Kinyoun and his fellow health officials continued on by deciding to set up a detention camp for the infected Asian population. Before plans for this camp could be finalized, a judge decided to take a look. The judge chose to postpone this meeting to discuss the details later on, but for the time being, the health officials were instructed to remove the Chinese and put them in the camps. However, more alleged death threats were placed on the Chinese people who were willing to go to the detention camp. No matter what, it was either get killed or stay silent.17

As time passed on, Surgeon General Wyman was told by Kinyoun that he was being approached by different people who were willing to give him a large reward if he would utilize his position in this case to revoke the regulations being put in place. However, it was not only Kinyoun being offered these rewards, but many were trying to convinced the physicians to “prove” the plague did not exist in order to lift the lockdown. Many of the physicians, including Kinyoun, chose not to accept the bribes because they were still determined to put an end to this plague. Unfortunately, on June 15, Judge Morrow decided to lift the quarantine based on his ruling of there being racial discrimination and conditions that were “too drastic” to put in place due to an alleged disease. Morrow also went ahead to state that the plague simply did not exist by saying, “personally, the evidence in this case seems to be sufficient to establish the fact that the bubonic plague has not existed and does not now exist in San Francisco.” From here on out, the lockdown was discontinued, due to being “unreasonable, unjust, and oppressive.”17

The court hearings did not stop there. On June 16, Kinyoun was in court due to being charged with interfering with the lives of the Chinese community. Although he still violated his court order, on July 3, Kinyoun was found not guilty. Usually people celebrate not being sent to jail; however, this arrest destroyed the influence of the Marine Hospital Service and their mission to get rid of the plague. If this was not enough for the senior officer, many San Franciscan businesses and newspaper companies continued to threaten Kinyoun while offering bribes in order to change his findings of the situation.19

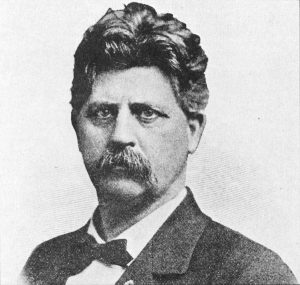

As the fall time of 1900 came around, newspaper editors did not budge as they still continued to ignore any upcoming news of the plague. There was one individual who shocked many medical professionals and health boards. The editor of the Pacific Medical Journal, Dr. Winslow Anderson, started to deny the plague existed. He decided to completely ditch his fellow colleagues and turn to the political side of this situation. Anderson then turned to the man who would soon turn Kinyoun’s life upside down, California Governor Henry Tifft Gage.20

Governor Gage was fully aware of this situation since May 31, 1900, when the secretary of state had asked Gage if he could take a look at the complaint regarding the quarantine happening in Chinatown. Once he arrived, Gage was not one to believe something like this could ever happen; however, he was ready to diffuse any rumor from being spread outside of San Francisco. While believing that there was no proof of the disease, he stated, “that the plague alleged to be here is either infection or contagious.” Gage then finally came to the conclusion that either none of this existed, or if there was evidence that it did, then this situation is “unreasonable and discriminatory.”21

By no surprise, on January 15, 1901, cases of the plague continued to rise in San Francisco. This did not stop Governor Gage from wanting to speak his mind to the California state legislature. “Could it have been possible that some dead body of a Chinaman had innocently, or otherwise, received a post mortem inoculation in a lymphatic region by someone possessing the imported plague bacilli, and that honest people were thereby deluded?” He continued to shame the Board of Health officials by calling them “plague fakers” that casted a shadow over the city of San Francisco and the entire state of California. Gage believed this was all caused by the “recklessness of certain city officials” who were led by Doctor Kinyoun.22

Gage’s expression of frustration continued as he asked the legislature if the importation of the plague bacilli or anything contaminated with the plague (which included all slides and cultures produced) without written authority from the State Board of Health be considered a life sentence to those found guilty. That was not the only suggestion he made. Gage decided to also recommend arresting people who published articles with different allegations and opinions involved in the existence of the plague (mainly targeted to those in the state of California) unless the State Board of Health had confirmed the facts. And to no one’s surprise, neither bills were passed.20 The legislature, who supported Gage’s words, decided to send a resolution to President McKinley on January 23 regarding the removal of Kinyoun. However, they felt that this punishment was “too mild,” so the legislature decided to add in the idea of hanging Kinyoun instead. 24

Kinyoun was heavily disheartened by this situation. “I did not know that a man occupying such a high position as the Governor of a State, could stoop so low as to lend himself to one of the lowest forms of persecution,” he wrote to his relatives. No matter what he did, he was painted as a fraud. As a last attempt to save his image, he sent a telegram to the surgeon general asking for help from this slander. Unfortunately, not even his own boss was willing to help.25 What is interesting about this predicament is how many politicians, businessmen, and citizens were not wanting to believe a highly accredited man. Despite all these great achievements of working with well-renowned scientists and discoveries of various bacterium, they were no match for the discrimination that covered Kinyoun’s image. 19

Eventually, President McKinley decided to step into the chaotic mess between the health officials and Governor Gage. If the situation were to worsen, the President was going to take matters into his own hands. The commission that dealt with the plague matters had sent Governor Gage the formal report in which it determined that the plague truly existed. In distress, Gage decided to hold a secret meeting to discuss how the state can cover up the plague completely. The meeting consisted of San Francisco Press and officials who were a part of the Southern Pacific Railroad; however, there were no doctors who attended. After taking time to deliberate, the men came to an agreement that no newspaper article in the city of San Francisco will mention or discuss the commission’s report that Gage received regarding the plague epidemic.27 They were to make it seem as if the plague was nonexistent.

Another crucial agreement that Gage pushed for was the extermination of Kinyoun in the city of San Francisco since he was the prime reason why the alleged plague was remaining existent. The game plan was for the editors and an attorney to make their way to Washington in order to stop the plague reports from being published to the Marine Hospitals Service’s Public Reports article. Not only were these men supposed to put a stop to the plague reports becoming published, but Gage also strongly wanted Kinyoun to be removed immediately.28

Unfortunately, the Secretary and the Surgeon General Wyman of the Marine Hospitals Service came to a final decision to not release the reports due to the increase in political pressure. This also led to the final moments of Kinyoun’s time in San Francisco. Washington officials who had agreed to not release the plague reports also agreed to Kinyoun’s departure from San Francisco.29 This is where it all ended for Dr. Joseph Kinyoun. The man who tried to push for the health of the public by warning them about the wretched plague.

If there is something that can be taken away from this mess of an event, it is that the health of the people comes first. There is no reason for non-medical professionals to step in and decide what the public should and should not hear if they themselves are not well-educated on the matters. What happened to Dr. Kinyoun and the bubonic plague was a prime example of how politics interfering in medicine can greatly impact public health in a negative way. Briberies, false information, and character defamation all led to the death of many people. This is not what medicine should be about. The main objective of a doctor in healthcare is to make their patient’s quality of life better than before they came to their appointment. Giving them the wrong information or spreading lies can lead to a creation of distrust within physicians which can further lead to a strained relationship between the doctor and patient. As unfortunate as this event was, time moves on and so does society.

- Myron J. Echenberg, Plague Ports: The Global Urban Impact of Bubonic Plague, 1894-1901 (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 213-214. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 113–114. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 114. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 116–117. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 118. ↵

- Marilyn Chase, The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco (New York: Random House, 2003), 31-46. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 115-119. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 119. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 121. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 122. ↵

- Charles McClain, “Of Medicine, Race, and American Law: The Bubonic Plague Outbreak of 1900,” Law & Social Inquiry 13, no. 3 (1988): 456. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 122–123. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 123. ↵

- Charles McClain, “Of Medicine, Race, and American Law: The Bubonic Plague Outbreak of 1900,” Law & Social Inquiry 13, no. 3 (1988): 473. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 123. ↵

- Charles McClain, “Of Medicine, Race, and American Law: The Bubonic Plague Outbreak of 1900,” Law & Social Inquiry 13, no. 3 (1988): 474. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 124. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 124. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 125. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 126. ↵

- Charles McClain, “Of Medicine, Race, and American Law: The Bubonic Plague Outbreak of 1900,” Law & Social Inquiry 13, no. 3 (1988): 500-501. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 127. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 126. ↵

- Marilyn Chase, The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco (New York: Random House, 2003): 80. ↵

- Marilyn Chase, The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco (New York: Random House, 2003): 80. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 125. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 128. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 128-129. ↵

- Philip A. Kalisch, “The Black Death in Chinatown: Plague and Politics in San Francisco 1900-1904,” Arizona and the West 14, no. 2 (1972): 129-130. ↵

15 comments

Michaell Alonzo

Hey Franchesca, congrats on the award for your writing. This post was so beautifully written and fascinating to read. This page has an astonishing quantity of specific information. It worries the potential spread of more illnesses and viruses. It’s also unsettling to think of how people will respond or attribute the outbreak to it. I believe that politics simply made everything worse and increased the level of public worry beyond what was necessary. I really adored the pictures you chose, which perfectly complemented the narrative you were presenting. I really appreciated how well-organized you were; it made the reading interesting for me.

Olivia Lauer

Congrats on your nomination! All of the information you put is all new for me. I had no idea that all happened in the world. It’s crazy that the non-medical people thought they knew more the the professionals and the doctors. When you said, “What happened to Dr. Kinyoun and the bubonic plague was a prime example of how politics interfering in medicine can greatly impact public health in a negative way. Briberies, false information, and character defamation all led to the death of many people.” I think it’s true because people put politics into almost everything.

Azeneth Lozano

The article was well-written and was an even more informational topic. However, this is the first time I heard of such dramatic events that lead up to the Bubonic Plague and all of the parties involved. It was proven in this article that the government tends to interfere sometimes with the health board and wants things to go smoothly, at least financially. In addition to learning more about the topic, the layout of the article was well constructed! I enjoyed reading the use of metaphors and the short sentences that made me read between the lines. Especially, the last paragraph! Congratulations on your nomination and your well-deserved award!

Lauren Deleon

What a well-written and topical article! Congrats on your award! I had never heard of this story before so it was interesting to see how turn-of-the-century events eerily mirror the much more recent response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In both instances, the San Fransico plague of 1900 and 2020’s covid outbreak, I find the media’s response to be particularly disturbing. Journalists jumping on the opportunity to discredit medical professionals is dangerous, and as this article shows sometimes even deadly.

Jose Luis Gamez, III

I enjoyed reading your article Franchesca. It was interesting to find out about this plague that spread quickly and killed many in the 1900s. This reminded me of the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Congrats on your nomination!

Amanda Uribe

Congrats on your nomination! This article was very insightful into the information that we recieve that has a different agenda than the truth. Sadly, this repeats itself too often in our society today. It has been 122 years since this plague happened and we still see racism towards people in the Asian community as well as mass distrust of medical professionals. I hope in the future we can learn from San Fransico Plague and it’s effects.

Jocelyn Elias

Congratulations on your nomination. Your essay is very informative and I completely agree with the statement stated in your article. We saw this through the covid-19 pandemic where people would rather listen to their governors and people who have no medical background which in the end cost millions of lives people should listen to medical professionals rather than just Politicians. Very well-written article.

Shecid Sanchez

Congratulations on your award nomination! I have actually never heard about this, but let just say you did an astonishing job connecting both pandemics and the amount of details that you provided. Overall what an amazing article and once again congratulations on your nomination!

Alyssa Leos

First of all I want to say congratulations on your article being nominated for an award! It’s crazy how the media could really take something out of context creating a panic. We should always listen to the professionals. It’s scary how even after finding out the lab results, the media still didn’t believe the arrival of the plague. This article was very informative. Again congratulations on your nomination. Well deserved!

Guadalupe Altamira

Congratulation on your nomination! This article was very informative and enjoyable to read with all the good details. It concerns how many more diseases and viruses can spread. It’s also frightening how people will react or blame it for the start of it. The panic people go into is no match to anything else but to make things worse race has to be involved with something started by things that are not human. Loved this article!