In the autumn of 1868, with the first whispers of winter in the air, Louisa May Alcott sat at her writing desk built by her father, deep in thought, with the weight of financial strain pressed on her shoulders—a familiar burden in her family. Determined to ease the pressure, Louisa used the talent that had always been her refuge—her writing. But this time, she felt it was different; it was not another simple piece created to earn money. She felt the need to tell a story from her heart, one that had been quietly growing inside her for years. As she began to write, memories of her own childhood rushed back, vivid and alive. She thought of her sisters; she knew deep inside that they would be an important part of her book, and she would portray them with vivid personalities.1

But her peace was short-lived. A new challenge arrived with a letter from her publisher: they wanted her to write a novel for girls. It was a genre she had little interest in, but one that could sell.2 Louisa, who preferred bold, adventurous tales, now faced a task that felt uninspiring. The writing process was far from smooth. Each day, exhaustion gripped her more tightly, and her health began to falter. Long hours hunched over her desk left her with splitting headaches, and the constant pressure from her publisher to move faster added to her fatigue. But she did not give up; she decided to pour her true self into one character—the spirited and independent Jo March.3

Louisa’s childhood had not been an easy one, filled with financial hardship and the constant worry of making ends meet. But it had also been filled with moments of great joy, moments of closeness with her sisters that had shaped who she was. As she poured these memories onto the page, she felt as though she were reliving those days, capturing the innocence and the struggles of her youth. She remembered the laughter and the tears, the struggles and the joys she had shared with her sisters—Anna, Elizabeth, and Abigail. Their bond had been strong, forged through years of hardship and love. Each sister had her own unique personality, and together they had weathered the ups and downs of life in their close-knit family. Louisa knew that these memories, these experiences, would become the heart of her new story. This book was not just about creating characters or telling a story—it was about preserving the essence of her family and the lessons they had learned together. She was writing from her heart, and in doing so, she was giving voice to something that had been buried within her for years.4 Louisa drew deep inspiration from her sisters and was committed to portraying them with the authenticity and depth they deserved. In the characters of Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy, she brought their distinct personalities to life. Meg, the caring eldest; Jo, the fiery and independent writer; Beth, the tender-hearted; and Amy, the driven artist—each character embodied aspects of Louisa’s own life and the close relationships she treasured with her sisters. As she continued writing, the story expanded beyond mere memories, growing into something much more profound and significant.

For Louisa May Alcott, the Civil War was an important period in her life. During the war, she had a plethora of experiences as a nurse. She was exposed to the brutal reality of war, leaving her a memory of who she was before the war. As she witnessed the suffering and the devastation, she decided to write a lighthearted domestic novel. The war just did not leave her emotional and physical scars; it left her with a growing sense of independence and a determination to change societal norms of that time. In her character Jo, Louisa found herself believing that Jo was going to be the voice to express herself and her beliefs. It was a way to challenge the expectations that had been forced on her as a woman and a writer.5 America in the nineteenth century was a society full of prejudice, where women were often dismissed and could not even vote; their work as writers was considered less serious compared to that of males. Louisa was one of the many women who were minimized just for her gender.6 Her publisher, Thomas Niles, persisted in asking Louisa May Alcott to write her book for young girls, reminding her that the market for children’s literature was growing, and they needed to capitalize on that trend.7 While she was writing about Jo and her story, something inside her changed; she no longer felt that she was writing for a profit; she was writing because she liked it. It was a way to express her frustrations and her abundant ambitions. With the story of the March family, she put her own voice, her frustrations, and her hopes. It became more than just a domestic tale. As the months progressed, she sank into the familiar creative vortex; she often forgot to eat or sleep.8

As she finished the final chapters, she felt an odd sense of satisfaction. She had poured her heart into this book, and though she still doubted its success, it had become an outlet for her emotions, her struggles, and her deepest desires. She did not just write a novel that, in the future, would become a classic; she wrote a book that people would cherish.9

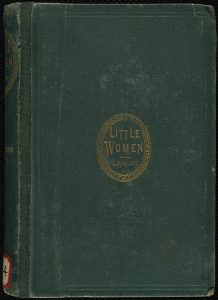

When Little Women was finally published in September 1868, after months of physical and emotional toil, Louisa braced herself for disappointment. She had grown used to rejection and knew all too well the sting of failure. Louisa May Alcott prepared herself for the worst. Having faced rejection and failure numerous times throughout her career, she knew how precarious the literary world could be.10 Her earlier works, while moderately successful, had not brought her the recognition or financial stability she desperately needed. But to her astonishment, the book became an immediate success. Letters flooded in from readers—particularly young girls—who saw themselves in the March sisters, who connected with their struggles and triumphs. Jo, in particular, struck a chord with readers who admired her independence and courage. The story resonated far beyond what Louisa had ever imagined. For the first time, these young girls felt represented in literature in a way that celebrated their daily lives, emotions, and dreams.11

With the success of Little Women, Louisa’s financial worries began to ease. The book sold rapidly, providing her with the stability she had so desperately needed. For the first time, she wasn’t writing simply to keep her family out of poverty—she was writing from a place of creative freedom. This shift marked a significant turning point for Louisa. No longer was she bound to the exhausting grind of churning out stories simply to make ends meet. Instead, she could focus on writing with passion, pouring her creative energy into projects that truly mattered to her. The overwhelming success of Little Women not only secured her financial future but also validated her talent in a way that perhaps she hadn’t fully believed possible. Her story, once doubted by her publisher, had resonated with readers across the country, particularly with young girls, who connected with the March sisters and their relatable struggles and triumphs. Her publisher, who had initially been hesitant about the project and unsure of its appeal, was now eager to capitalize on its momentum. With the book’s astonishing popularity, they quickly encouraged Louisa to continue the story, suggesting that she write a sequel, which she did in 1869, releasing Little Women, Part Two to equal success.12

In the end, Louisa May Alcott had defied the prejudices of her time and, in doing so, had written herself into literary history. Louisa May Alcott’s novel, Little Women, serves as a source of inspiration, particularly through the characters of the March sisters. They demonstrate a pathway to challenge societal expectations. Previous generations have also derived comfort and inspiration from this narrative, largely due to Jo March—a character who defied the traditional roles of women in her society. Alcott, perhaps unwittingly, crafted a tale that resonates with the hearts of countless individuals across generations.13

- Harriet Reisen, Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2009), 214-216. ↵

- Madeleine B. Stern, Louisa May Alcott (Boston: Little, Brown, 1950), 169. ↵

- Susan Cheever, Louisa May Alcott (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 251. ↵

- Harriet Reisen, Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2009), 214-216. ↵

- Martha Saxton, Louisa May Alcott: A Modern Biography, 162. ↵

- Susan Cheever, Louisa May Alcott (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 126. ↵

- Susan Cheever, Louisa May Alcott (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 259. ↵

- Susan Cheever, Louisa May Alcott (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 266. ↵

- Yona Zeldis McDonough, Louisa: The Life of Louisa May Alcott, illustrated by Bethanne Andersen (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2009), 32. ↵

- Harriet Reisen, Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2009), 248. ↵

- Reisen, Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women, 252. ↵

- Harriet Reisen, Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind Little Women (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2009), 252-255. ↵

- Martha Saxton, Louisa May Alcott: A Modern Biography, 163. ↵

4 comments

Amrie Cortez

I have always loved this book! I didn’t know the March sisters were based off of Alcotts real sisters, that must have made the book more personal to Louisa! It’s such a interesting detail that made Alcott feel a deeper connection while writing. It must have been tough for her not knowing if the book was going to be successful.

Natalia De la garza

This infographic is excellent! It vividly portrays Louisa May Alcott’s journey in writing Little Women, highlighting how her personal experiences and family relationships influenced the novel.

Alysia Cano

Louisa May Alcott’s *Little Women* not only became a literary sensation but also served as a powerful reflection of her own struggles and aspirations, particularly through the character of Jo March, who defied societal expectations of women. By channeling her personal experiences and frustrations into the March sisters, Alcott created a timeless story that continues to inspire generations, especially young women, to challenge traditional roles and embrace their individuality.

Danielle Villanueva

I found this article about Louisa May Alcott’s journey to writing “Little Women” really inspiring. It was fascinating to learn how she wrote a book based on her own family experiences and challenged the expectations for women writers of her time. I wonder how difficult it must have been to write a book while struggling financially and facing societal challenges.