“For it matters not how small the beginning may seem to be: what is once well done is done forever” – Henry David Thoreau 1

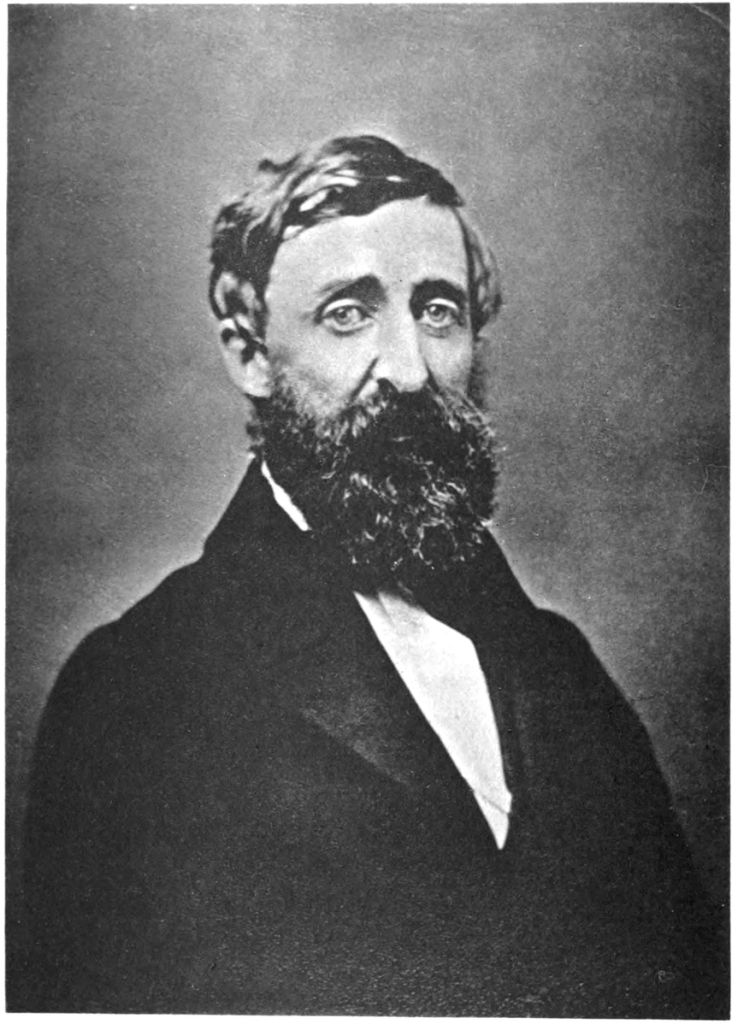

This ideology and Henry David Thoreau’s actions that would lead to it, were hardly what he may have thought would change people’s minds in 1849. Yet his ideas would later spark revolutions that would change the entire world. Born in humble beginnings, it seemed that Henry David Thoreau had been fighting for justice of the people all his life. Henry’s vocation to act and rise up to the podium to speak out against the injustices was something destined. Like the makings of a great hero of an untold story, Henry’s legacy was only beginning and the future he would help create would be a far cry from that of a simple man living in the wilderness of the 1840’s.2

Henry David Thoreau never set out to be a hero, a leader, or even a figure worth remembering. That was saved for his friends, like Ralph Waldo Emerson, who weaved tales of greatness with pen, ink, paper, and words. No, Henry was simply an intellectual and a writer who craved equality and justice for all, not only for those who could afford their freedoms and luxuries, such as a vote, but for all souls who set foot on soil and called themselves human. He was only a man who would sit quietly in a log cabin, a home he had built with simple tools, his hands, and grit – while he sat and thought about the land around him and what it meant to be part of an ever-changing world.3

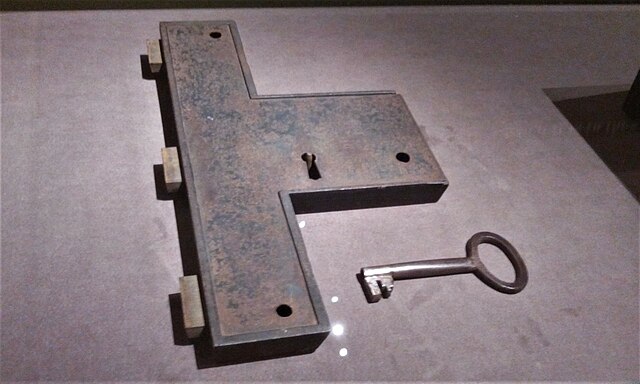

One could only dream about the ideas he came up with on this modest piece of land; however, never would anyone think that a simple disagreement would spark an idea of revolution…one hundred years in the making with its echoes leaving their voices crying for change. It was on this ordinary late July day in 1846 that Henry was arrested for tax delinquency. To Henry’s surprise, he was informed that the property had six years of poll taxes that were unpaid and it was now Henry’s responsibility to pay them. However, Henry knew that the tax money went to causes such as the Mexican-American War and slavery: two causes he felt were not only unjust but unfair as the money would only line the pockets of owners and the politicians with undeserved wealth. It was money that had no business being used in blood and tears; certainty not being used in any way of interest towards the American people and not in ways that would soothe Henry’s conscious. So, Henry did what any radical, extremist fanatic would do: he refused to pay his taxes.4

It wasn’t that a man like Henry wouldn’t know the consequences of such actions – by refusing to pay, thus breaking the law, he would be arrested, which he knew, and he was. Swiftly. No, he took the punishment without fuss, without violence, and without a dramatic fight that one would see in headlines in tomorrow’s newspapers. No, he was taken to spend a night in jail. Calm, if frustrated, he spent only one night before he was released the very next morning to the aunt who paid his dues.5

He had made it clear: no tax money should be paid that would support causes he was vehemently against. His aunt had paid no mind to this, as she had paid the very taxes that would gain Henry’s freedom, and that tax money would yet go towards supporting the system that kept millions enslaved.6

It wasn’t as if they didn’t have the money. Henry could have paid it whenever he wished, but that wasn’t his point. Could the average American, indeed as Henry was an American and a proud one at that, be so easily swayed by a dollar? How could the ones in power be expected to change society towards the good of the many against those who could afford to sway the populace? Or perhaps something much more frightening…if change were possible, how would someone get the people to care, especially about their own interests and conscious minds and souls?7

That is the question that left him subdued and listless; however, it was his good luck that he had a cabin and a pond and the essentials to live, so he could think.

And he did. For almost two years he pondered this question and like many great thinkers of his time and beyond…he wrote his ideas down. Letter after letter he would write until the nonsensical letters formed iron-clad sentences that transformed into fiery speeches that his voice carried across lecture halls starting in the winter of 1848.8

No longer would he remain silent and keep these ideas to himself. What good are ideas if they cannot be spread, used, and transformed? Why even then speak of the injustice? Henry would speak about his night in the Concord jail – the very jail he was taken to when he was arrested originally.9

From each lecture, Henry spoke of ideals and what it meant to have them, and what it meant to protect them. They were ideals that would stay with a person long after the consequences had been settled and debts paid. This concept was something that Henry was most familiar with.10

Why even as a young man teaching at the Concord Public School, he was there barely a term before he quit because of the practice of corporal punishment. Even Henry would not harm a student and go against his ideals that a person is not responsible for the evils of man, but that didn’t mean one had to act on it.11

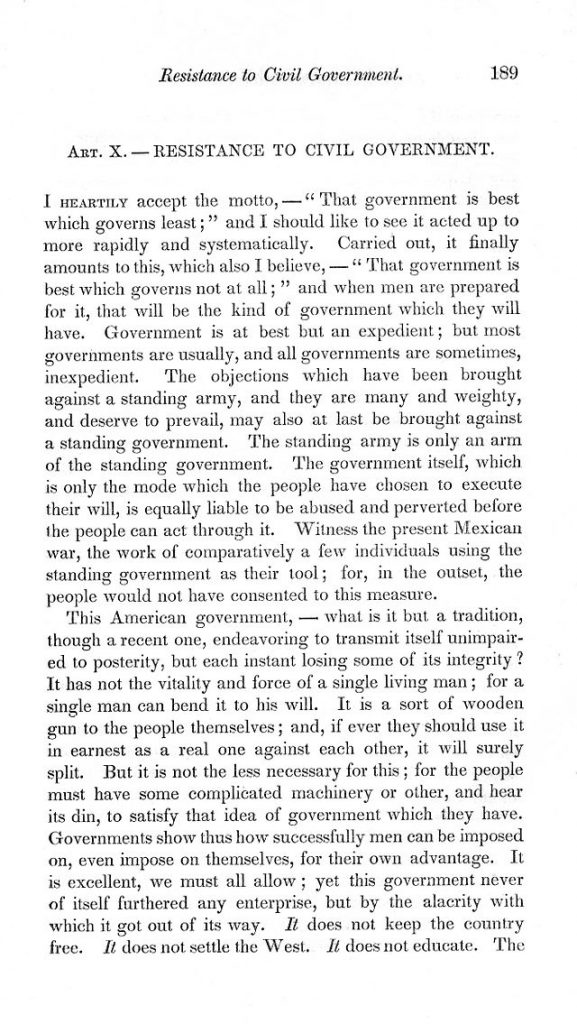

That is the idea and core of what resistance is, after all. This was a major point in his lecture series as he began speaking. Once word had spread, his speeches had risen in popularity as more and more people wanted to hear him speak. With the popularity of his speeches, they were revised to be “Resistance to Civil Government” – a series of essays on ideas that Henry had fought for and ideas that every person has a right to live by. Because the government of a land has the power to make laws, that didn’t mean the people of the land had to follow these laws, especially if the laws went against the people themselves.12

If a law is unjust and upheld by just people, what then? What does that say about that system of government? If a law is challenged by those it was meant to guide and protect, and if the people are struck down instead by the unjust words written by lawmakers, what does that say? In Henry’s words, “I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward. It is not desirable to cultivate a respect for the law, so much as for the right. The only obligation which I have a right to assume is to do at any time what I think right.”13

In other words, if a law is unjust then wouldn’t the just thing to do be to break it? To bring about change and improve what is unjust, one must realize what may be broken. This was a radical idea in 1849 and still a radical idea in 1944 when a freshman student at Morehouse College by the name Martin Luther King Jr first read about it in “Civil Disobedience” and posthumously renamed “Resistance to Civil Government.”14

“Resistance to Civil Government,” | Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The ideas written by Henry David Thoreau became a foundation for the Civil Rights Movement, where the later-named Dr. King would protest the unjust laws of the land by marching peacefully or encouraging those to sit quietly and steadfastly.15

It was a cornerstone idea to protest civilly, without fuss and without violence, and without dramatic fights that would make headlines and be in tomorrow’s news. Although in some cases fights did happen and sometimes it was unavoidable, the main idea was to show the injustice and lead by example, to show and prove to people that you have a right to make your voice heard in a situation where you are being asked to compromise your very being for the sake of the law.16

Just as Henry more than a hundred years previously had sat steadfastly in a jail cell to protest those unjust laws, Dr. King took up Henry’s example by peacefully protesting an oppressive government in a fight for a dream where all could be free.17

Henry David Thoreau never set out to be a hero or a leader or a radical. It was never the intention to garner titles of such notoriety or awe and in some cases… suspicion and fear. Henry David Thoreau, for all intents and purposes, was someone just like you and me. He was a person with ideals, someone who wanted to see the betterment of society and the people living in it. Henry David Thoreau set out to try to make that happen in whatever way he could. In his case, it was with words, and ink and paper…and he went on to spin grand tales of freedom, justice, beauty, and equality. That, in his words, would be the marching of footsteps on streets, of calls for justice in screams and whispers, of people fighting for the same ideas for years to come. From 1848 to 1944 to 2024…the ideas have never left us. They have evolved and changed and improved…for what good are ideas if they do not transcend time?18

- “Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience: Resistance to Civil Government (Auckland, NEW ZEALAND: Floating Press, 2009), 19. ↵

- Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience: Resistance to Civil Government (Auckland, NEW ZEALAND: Floating Press, 2009), 5. ↵

- Joel Myerson, The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau, The Cambridge Collection (The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1995), 45. ↵

- Joel Myerson, The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau, The Cambridge Collection (The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1995), 195. ↵

- Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience: Resistance to Civil Government (Auckland, NEW ZEALAND: Floating Press, 2009), 56. ↵

- Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience: Resistance to Civil Government (Auckland, NEW ZEALAND: Floating Press, 2009), 8. ↵

- Joel Myerson, The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau, The Cambridge Collection (The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1995), 195. ↵

- Joel Myerson, The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau, The Cambridge Collection (The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1995), xvi. ↵

- Joel Myerson, The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau, The Cambridge Collection (The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1995), 2. ↵

- Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience: Resistance to Civil Government (Auckland, NEW ZEALAND: Floating Press, 2009). ↵

- Joel Myerson, The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau, The Cambridge Collection (The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1995), 6. ↵

- Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience: Resistance to Civil Government (Auckland, NEW ZEALAND: Floating Press, 2009), 8. ↵

- Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience: Resistance to Civil Government (Auckland, NEW ZEALAND: Floating Press, 2009), 6. ↵

- “Civil Disobedience and the Legacy of Martin Luther King Jr.,” Westmont College, accessed November 5, 2024, https://www.westmont.edu/. ↵

- “Civil Disobedience and the Legacy of Martin Luther King Jr.,” Westmont College, accessed November 5, 2024, https://www.westmont.edu/. ↵

- “Investigating the Meaning and Application of Civil Disobedience Through Thoreau, Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.,” The Nonviolence Project, March 16, 2024, https://thenonviolenceproject.wisc.edu/2024/03/16/investigating-the-meaning-and-application-of-civil-disobedience-through-thoreau-gandhi-and-martin-luther-king-jr/. ↵

- U. S. Mission Korea, “Martin Luther King, Jr. : I Have a Dream Speech (1963),” U.S. Embassy & Consulate in the Republic of Korea, February 20, 2017, https://kr.usembassy.gov/martin-luther-king-jr-dream-speech-1963/. ↵

- Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience: Resistance to Civil Government (Auckland, NEW ZEALAND: Floating Press, 2009), 39. ↵

3 comments

Kaitlyn Villanueva

This was truly so amazing! I find it hard to sometimes stay focused when learning about history but I actually found this so interesting and I loved learning about this protest and how it turned into something greater. This was very well said and really makes you think about how powerful someones voice can be.

Natalia De la garza

This infographic is excellent! It vividly illustrates Henry David Thoreau’s journey from humble beginnings to becoming a pivotal figure in advocating for justice and equality.

Danielle Villanueva

I really enjoyed learning about how Thoreau’s small protest against unfair taxes turned into something much bigger. The article explained how his ideas about standing up peacefully against injustice helped inspire the Civil Rights Movement. I’m curious how Thoreau would feel knowing his writing influenced such important changes in society decades later. What other movements might have been shaped by his philosophy?