For many people, the familiar concepts of preservation, endangerment, and extinction call to mind environmental movements that aim to protect living organisms in the natural world. Now more than ever, similar movements are growing in relevance for the protection of nonbiological – yet no less animate – organisms: languages. Languages continuously adapt in response to cultural context, allowing speakers and signers to effectively articulate and communicate their lived experiences. For example, most speakers of Standard American English today would find the Old English spoken a thousand years ago incomprehensible. Lexical borrowing, the transmission of vocabulary from one language to another, commonly occurs in multilingual societies. The development of hybrid languages and dialects also adds to linguistic diversity. Linguistic evolution is a natural and enriching occurrence for speech communities. Biological metaphors become especially apt when discussing threats to a language’s vitality. Languages can become endangered and, if not studied for preservation, undergo extinction. However, unlike biological organisms, an extinct language can be resurrected.

The loss of languages has lasting impacts on those who speak and study them. In his book On the Death and Life of Languages, the French linguist Claude Hagège advocated for the preservation of language by arguing that “human languages are one of the most elevated manifestations of…cultures”(4). The Chicana scholar Gloria Anzaldúa further associated language and personal identity by claiming that harm done to her language is harm done to her: “ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity – I am my language” (59). The life and death of language is not a linear process. Because languages are so deeply influenced by the culture, politics, and history of their speech communities, there is no universal formula that can be applied to predict or quantify linguistic extinction. Languages can undergo gradual shifts, slowly fading out of common use. They can also be quickly and violently suppressed. Consequently, the practice of reviving an extinct or endangered language relies heavily on an understanding of the factors causing that language’s decay. In order to effectively combat language extinction, linguists must pursue preservation of the language’s aspects (such as literature, grammar, and phonetics) as well as revitalization efforts that make documented materials and learning opportunities accessible to speech communities.

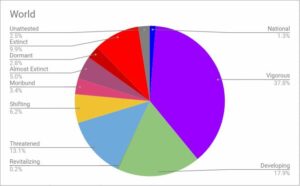

The linguist Wolfgang Dressler, referencing the 2010 UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, judged 43% of the world’s languages to be endangered (120). More recently, in October 2018, the language learning platform Glossika released a Language Vitality Report, putting the rate of endangerment into perspective. It recorded that out of 8,248 languages worldwide (considering dialects and unattested languages), there were 4,670 healthy languages, 2,265 languages in various states of decline, and 806 extinct languages (Campbell 14). Australia exhibited the most pronounced decline, with 131 Aboriginal languages under threat and 180 extinct; the majority of these extinct languages come from the Pama-Nyungan language family (Campbell 94-95). In 2003, UNESCO established a severity scale to categorize and discuss endangered languages. Safe languages, spoken with fluency at all generational levels and steadily transmitted from older to younger speakers, are not included in the Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Vulnerable languages are the native language of most speech community members but are confined to private social spheres such as the home rather than public social spheres. 1 An example from the United States is Choctaw (Moseley 9). Parents and older generations still speak definitely endangered languages but these languages are no longer taught as first languages to children; as children grow up speaking the dominant language, the family may communicate through code-switching. 2 Mohawk is a definitely endangered language from the Northern United States and Southern Canada (Moseley 9). Severely endangered languages are only spoken by generations older than the parents; the parent generation may understand the language but cannot speak it, while the children neither speak nor understand it. 3 Tenharim is a severely endangered language from Brazil (Moseley 19). Critically endangered languages are spoken occasionally by generations older than grandparents, and communities of fully fluent speakers are scarce. 4 Nihali, spoken in India, is critically endangered (Moseley 47). When a language is declared extinct, there are no longer any known native speakers or remembered. 5 Ngarla, a Western Australian language, is considered extinct (Moseley 57). This endangerment scale is flexible, as severely threatened or even extinct languages can potentially transition to a stage of greater security.

Specific terminology is essential in this discourse. The biological metaphor of life and death is often helpful to describe a language’s status. Still, the phrase “dead language” can cause confusion. Latin is a commonly cited example of a dead language. It is “dead” because it is no longer spoken conversationally or used in circles of business or commerce, but it is not threatened. It is comfortably established as a subject of academic value and prestige. Extinct languages have no native speakers, scholars, or resources for learning. Similar to the scale of language endangerment, it is helpful to consider the fluency of a threatened language as a spectrum. Linguists reference speakers’ typology to discuss fluency variations within a speech community. This typology comprises native fluent speakers, semi-speakers, terminal speakers, and rememberers (Grinevald 64). Native fluent speakers use the endangered language as their first language; they may be monolingual or bilingual with a leaning towards their first language (Grinevald 64). Semi-speakers are bilingual, with varying proficiency levels in the endangered language; they may speak a nontraditional form of the endangered language, influenced by the other languages they speak (Grinevald 65). Terminal speakers speak and understand only partial elements of the endangered language (Grinevald 65). Rememberers are those who can no longer speak the endangered language but may possess some knowledge of it (Grinevald 65).

Various social, political, economic, historical, and cultural factors threaten languages and dialects. Sometimes, languages slowly decline, with a dominant language overtaking a minority language. This is known as language shift (Dressler 121). Wolfgang Dressler developed a causal chain to evaluate the general sociological factors influencing language shift. The most widespread systemic linguistic influence originates on the socio-political level, especially in the form of national language policies affecting education, nationalism, and imperialism (Dressler 121). The language of a colonized people is often suppressed by the colonizing force, alienating the speakers from their culture and ensuring assimilation to the dominant language. The socio-economic level impacts language shift due to a more significant potential for geographic mobility (Dressler 122). The socio-cultural level concerns the general cultural attitude towards the language. Racism is a major disparaging factor that delegitimizes a language and its speakers. Lack of representation in the media also leads to a perceived lack of prestige (Dressler 122). The socio-psychological level describes a speaker’s attitude toward their language (Dressler 122). A semi-speaker or terminal speaker may struggle to identify with their language and lack conviction in the practicality of retaining it. On a linguistic level, an endangered language no longer widely used is perceived as less functional (Dressler 122). There are fewer incentives to learn it and greater pressures to shift to the dominant language. Disparities may arise between older fluent speakers and younger semi-speakers who speak different versions of the same language. Dressler recognizes that a definite indicator of language decay is the break in intergenerational transmission of the minority language (122). In this way, language decay can occur in a matter of generations. Oral linguistic traditions and pronunciation standards are lost as older speakers cease to teach younger speakers.

Dressler’s causal chain pertains to gradual language endangerment through language shift. However, one of the most devastating forms of language extinction is the loss of the speakers themselves. Threats to speakers’ physical well-being are a threat to their cultural and linguistic well-being as well. Such threats include displacement, natural disaster, famine, disease, colonization and exploitation, war, and ethnic cleansing or genocide (Crystal 70-76). A notable example of this can be seen in the history of the United States’ colonization of Hawai’i. In the 100 years following initial Western contact in 1778, 94% of the Hawaiian population was lost to “venereal diseases, tuberculosis, influenza,” and other respiratory infections (Warner 70). The U.S. established further control over the Hawaiian government, land ownership, and customs to withhold political power and cultural agency from the Hawaiian people (Warner 70). In addition to these physical threats, the U.S. government outright banned the use of the Hawaiian language in schools in 1896; this suppression of language and culture was often enforced with corporal punishment and public humiliation (Warner 70-71). As of 2010, Hawaiian is still considered a critically endangered language (Moseley 58).

Despite this bleak prognosis, there is hope for endangered and extinct languages through language revitalization efforts. Revitalization is a broad term for preserving, legitimizing, and educating threatened languages. Leanne Hinton, a linguist specializing in the revival of Native American languages, defines the goal of language revitalization as “the development of programs that result in re-establishing a language which has ceased being the language of communication in the speech community and bringing it back into full use in all walks of life” (Fitzgerald e2). Language revivalists assume the daunting task of checking and reversing mortality. Given the urgency caused by the decrease in fluent speakers and the prospect of irretrievably lost knowledge, the primary concern of linguists has traditionally been preservation. The basis of this approach is a descriptive model that functions to catalog the structures and systems of a language and explain how the language works as an independent entity. This includes data on grammatical characteristics such as phonology (the pattern of sounds in the spoken language), morphology (the structure of individual words), vocabulary, and writing system. A significant objective in descriptive linguistics is to assemble a “trilogy” consisting of a dictionary, a grammar, and a collection of literature written in the language of interest (Himmelmann 345). Many contemporary linguistics view descriptive linguistics as an outdated and incomplete model of preservation. It can foster an “a-social conceptualization of language,” as researchers may “tap the linguistic knowledge of one or two speakers” rather than making more comprehensive observations of the speech community as a whole (Himmelmann 341). The German linguist Nikolaus Himmelmann proposed “multifunctional long-term documentation” to integrate and augment description (345). Linguists practicing documentation approach language as a system of “behavior and knowledge…of the linguistic practices in a given speech community” rather than “an economical set of abstract units and rules” (Himmelmann 346). The trilogy and other aspects of descriptive linguistics are retained. Still, they must be “multifunctional” – available and comprehensible for linguists, researchers in other fields, non-linguist policymakers, and the speech community (Himmelmann 346). Documentation and other forms of preservation are important steps in the revitalization process, but if linguists stop here, they are left with a language that is “fossilized” rather than resurrected.

Ultimately, the soul of a language is the speakers themselves. David Crystal criticizes academics who view speech communities as mere data mines. This behavior is as “unacceptable” as it would be if “doctors collected medical data without caring what happened subsequently to the patients” (145). Amassing a database of information on the endangered language is an essential milestone for revitalization. Still, the main focus is establishing opportunities for the speech community to reclaim its language. One significant barrier to this lies in the competing interests of linguists and speech communities. Documented language information is often written in linguistic jargon intended for an academic audience or in a dominant language (such as English) that excludes speakers of a minority language. Speech communities may not be given access to information databases once assembled. Colleen Fitzgerald, addressing the lack of quality control for documentation, developed a list of standards for assessing the integrity of documentation archives. The most vital standard is accessibility.

The internet is often a valuable tool for archiving written information and video and audio recordings of pronunciation. Documented information needs to be stored in a stable repository, providing “long-term curation” and unrestricted access to both the corpus of work and the metadata (Fitzgerald e5). Secondly, the archived data must be of high quality. One way to achieve Himmelmann’s standard of multifunctional documentation is to provide annotations and contextual information explaining the data to non-linguistic, as well as information on the research methodology used to gather data (Fitzgerald e5). Audio and video files can accompany time-aligned transcriptions (Fitzgerald e5). Finally, the quantity of data improves the database’s efficacy. Fitzgerald suggests researchers involve speakers with diverse fluency ranges (from native fluent speakers to rememberers), from diverse generational, regional, and gender backgrounds, or from multiple language dialects (Fitzgerald e5). It is also valuable to include texts from a range of genres (Fitzgerald e5).

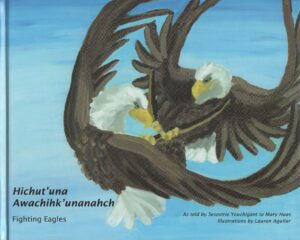

The work of making dying tongues speak again is formidable even theoretically. Still, current programs successfully integrate linguistic and social contexts, empower speakers, and provide a model for progress. The Tunica Language Project, established in August 2010, is a collaborative revitalization program between the Linguistics Department of Tulane University and the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana (“Tunica Language Project”). The Tunica language died on December 6, 1948 along with its last native semi-speaker, Sesostrie Youchigant (“The Tunica Language”). The only information left to work with was documentation from the three previous researchers who strove to preserve the language: Albert Gatschet, John Swanton, and Mary Haas (“The Tunica Language”). Using these materials, participants work to create an updated orthography (system of spelling) and pronunciation to restore the language to common use. They have developed a dictionary and descriptive grammar, which undergo continual updates. Tulane University makes these resources available by offering summer intensive courses and disseminating digital resources for learning Tunica, including recordings of pronunciation guides (“Tunica Language Project”). The Tunica-Biloxi tribe has hosted children’s summer language camps at the Louisiana reservation, teaching the basics of Tunica: “greetings, numbers, colors, basic verbs”, and songs (“Summer Language Camp”). Program participants encourage the publication of Tunica literature, including children’s books and prayers. The positive progress of the Tunica Language Project hinges on the accessibility of language learning resources and opportunities for speech community and researcher collaboration.

The United Nations General Assembly has appointed 2022-2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous Languages (“Indigenous Languages Decade”). This is a step forward in validating the preservation and revitalization of endangered indigenous languages, and it encourages the collaboration of interdisciplinary researchers and other stakeholders. The IDIL’s ambitions are broken down into ten distinct themes, including the integration of Indigenous languages in education, the promotion of public services in Indigenous languages, the promotion of digital empowerment for Indigenous languages, and the fostering of economic opportunities for Indigenous speech communities (“Global Action Plan”). Readers interested in further information are encouraged to consult the United Nations General Assembly Global Action Plan. During the IDIL, even individuals without a formal linguistics background can support the preservation and revitalization of languages. Those interested in providing resources for their own languages, organizing communities, or learning more about Indigenous languages can register with UNESCO to get involved. Endangered languages are invaluable and resilient, like those who speak, write, and sign them. The cooperation of speech communities, researchers, and informed individuals today ensures that endangered languages worldwide have a future.

Works Cited

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books, 1987, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/anzaldua-borderlands-la-frontera/mode/2up.

Campbell, Michael. “Glossika Language Vitality Report 2018”. Glossika, 5 Nov. 2018, https://d310pm6npapqqb.cloudfront.net/free-download/Glossika%20Language%20Vitality%20Report%202018.pdf

Crystal, David. Language Death. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Dressler, Wolfgang U. “Independent, Dependent and Interdependent Variables in Language Decay and Language Death.” European Review, vol. 26, no. 1, 2018, pp. 120-129. ProQuest, https://blume.stmarytx.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/independent-dependent-interdependent-variables/docview/2557397642/se-2, doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798717000370.

Fitzgerald, Colleen M. “A Framework for Language Revitalization and Documentation.” Language, vol. 97 no. 1, 2021, p. e1-e11. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2021.0006.

“Global Action Plan of the International Decade of Indigenous Languages”. UNESCO, 16 Jan. 2024, https://www.unesco.org/en/decades/indigenous-languages/about/action-plan.

Grinevald, Colette. “Speakers and Documentation of Endangered Languages.” Language Documentation and Description, vol. 1, 2003, pp. 52-72. Language Documentation and Description. https://doi.org/10.25894/ldd306.

Hagège, Claude, and Jody Gladding. On the Death and Life of Languages, Yale University Press, 2009, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1npgk7.4.

Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. “Reproduction and Preservation of Linguistic Knowledge: Linguistics’ Response to Language Endangerment.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 37, 2008, pp. 337–50. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20622629.

“Indigenous Languages Decade (2022-2032).” UNESCO. https://www.unesco.org/en/decades/indigenous-languages.

Moseley, Christopher and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. 3rd ed., UNESCO, 2010. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187026.

“Summer Language Camp”. Tunica Language Project: A Collaboration of the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana and Tulane University. https://tunica.wp.tulane.edu/our-projects/summer-language-camp/

“The Tunica Language”. Tunica Language Project: A Collaboration of the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana and Tulane University. https://tunica.wp.tulane.edu/about/about-the-tunica-language/

“Tunica Language Project”. Tunica Language Project: A Collaboration of the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana and Tulane University. https://tunica.wp.tulane.edu/about/about-the-tunica-language-project/

Warner, Sam L. No’eau. “‘Kuleana’: The Right, Responsibility, and Authority of Indigenous Peoples to Speak and Make Decisions for Themselves in Language and Cultural Revitalization.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 1, 1999, pp. 68–93. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3195982.

- Moseley, Christopher and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. 3rd ed., UNESCO, 2010. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187026. ↵

- Moseley, Christopher and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. 3rd ed., UNESCO, 2010. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187026. ↵

- Moseley, Christopher and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. 3rd ed., UNESCO, 2010. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187026. ↵

- Moseley, Christopher and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. 3rd ed., UNESCO, 2010. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187026. ↵

- Moseley, Christopher and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. 3rd ed., UNESCO, 2010. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187026. ↵

4 comments

djorn1

Mary, Finally read your article, so well done and informative. I had to get an email connection from the University center to read it. Bro. Dix spent several hours making that happen. Hope you stay interested in keeping languages alive. Bro. Del

Silvia Benavides

This article was very informative. I enjoyed the mention of Gloria Anzaldua and the charts provided. Awesome work!

Mariana Chamorro

Mary, your publication on endangered languages is fantastic! You explain why languages are so important to cultures and individuals, showing how they shape identities and communities. Your detailed look at why languages become endangered, and the efforts to save them is fantastic. Keep up the great work!

Rhys Williams

I found your exploration of language loss and preservation deeply engaging. The quote from Claude Hagège, “human languages are one of the most elevated manifestations of…cultures,” underscores the profound connection between language and culture, emphasizing the importance of preserving linguistic diversity. Similarly, Gloria Anzaldúa’s assertion that “ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity – I am my language” poignantly highlights the intimate link between language and personal identity. Your discussion eloquently illustrates the complexities of language extinction, emphasizing the need for multifaceted preservation and revitalization efforts to combat its effects effectively.