In the summer of 1861, the air was thick and tensions were strong. The whole of the United States seemed to hold its breath as it stood at the brink of a chasm from which there could be no return. The American Civil War had finally erupted, fueled by decades of perceived injustices, inequalities, and divisions that could no longer be resolved through treaties or compromises. As both the Union and Confederate armies prepared for the impending battle, soldiers began to fervently write back home to their loved ones, exposing their deepest fears and secrets to find some sense of stability among the uncertain conditions brought on by the war. Sullivan Ballou, a Union officer, wrote one such letter to his wife, Sarah Ballou. While other letters expressed similar sentiments, Ballou’s letter profoundly and earnestly expressed his love of country and love of his home.

Sullivan Ballou’s letter offers important insight into the shifting and uncertain times of the Civil War, providing a deeper understanding of his personal emotions, as well as the broader socio-political context of the War. By delving into the messages within this letter, it is possible to gain a new perspective on the driving forces that cultivated a time of confusion and chaos and find new meaning in what love, patriotism, and duty meant. By understanding the true meaning of what these meant to people like Sullivan Ballou, we may be able to connect with the figures of the past.

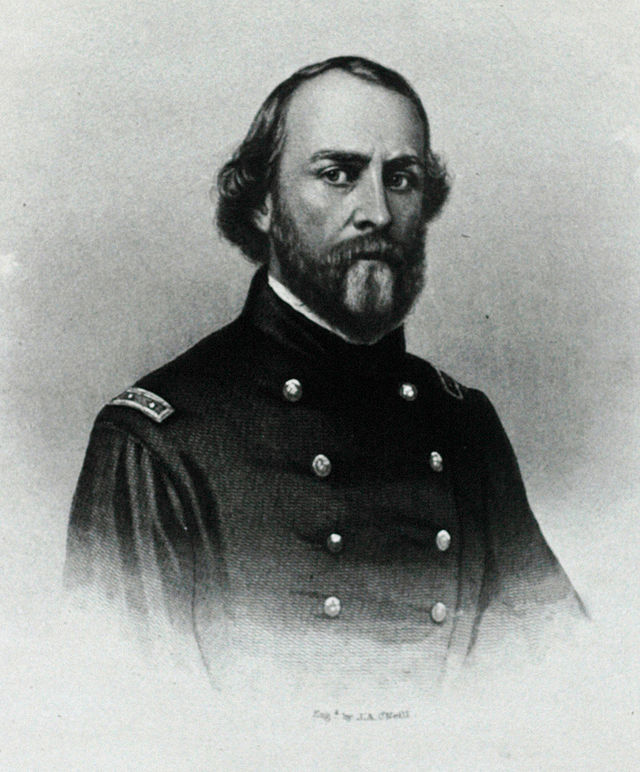

Despite the patriotic ideals detailed in the letter, Sullivan was not originally involved in the army, though he was still a man of honor. Prior to the Civil War, Ballou had been a lawyer who was serving in the Rhode Island legislature. Ballou even campaigned for Abraham Lincoln in 1860. However, on June 11, 1861, he was commissioned as a major in the 2nd Rhode Island Volunteers to serve in the Union army. The next month, and just one week before the Battle of Bull Run on July 14, 1861, he wrote a farewell letter to his wife Sarah from Camp Clark in Washington D.C. In the letter, Ballou begins by telling Sarah that the regiment would be mobilizing in a few days and he had a strong inclination to write to her. Throughout the course of the letter, Ballou describes how he feels the need to defend what he believes is right, going so far as to say that he is willing to die for this cause:

“If it is necessary that I should fall on the battlefield for my country, I am ready. I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in, the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American civilization now leans upon the triumph of the government, and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution, and I am willing, perfectly willing to lay down all my joys in this life to help maintain this government, and to pay that debt.”1

This intense feeling of patriotism is again reiterated in the lines: “A pure love of my country, and of the principles I have often advocated before the people, and ‘the name of honor, that I love more than I fear death,’ have called upon me, and I have obeyed.”2

However, despite his willingness to lay down his life for the causes that he so strongly believes in, he confides to Sarah that he has an ongoing internal struggle between serving his family and serving his country. His struggle is highlighted in lines such as:

“But, my dear wife, when I know that, with my own joys, I lay down nearly all of yours, and replace them in this life with cares and sorrows… is it weak or dishonorable, while the banner of my purpose floats calmly and proudly in the breeze, that my unbounded love for you, my darling wife and children, should struggle in fierce, though useless, contest with my love of country.”1

This internal struggle is further emphasized when Sullivan declares, “Sarah, my love for you is deathless. It seems to bind me with mighty cables, that nothing but Omnipotence can break; and yet, my love of country comes over me like a strong wind, and bears me irresistibly on with all those chains, to the battlefield…”4

Despite Sullivan repeatedly stating how his love of country overpowers his love of family, it is still evident that he cares deeply for his family and wishes that he did not have to choose between the two. His love for his family is seen in one of the most powerful segments of the letter, where Sullivan writes: “… but something whispers to me perhaps it is the wafted prayer of my little Edgar that I shall return to my loved ones unharmed. If I do not my dear Sarah never forget how much I loved you nor that when my last breath escapes me on the battlefield, it will whisper your name… But Oh Sarah! If the dead can come back to this earth and flit unseen around those they love I shall always be with you in the brightest day and the darkest night…”5

Unfortunately, Sullivan was injured during the Battle of Bull Run, when a six-pound cannon shot shattered his leg, and he then died of his wounds on July 28, 1861. On the surface level, Sullivan Ballou’s letter seems to be nothing more than correspondence between a soldier and his family. However, this letter offers insight into the social and political conditions surrounding the Civil War. Therefore, it is important to look into the surrounding context of the letter in order to gain a fuller sense of what Sullivan is trying to convey and what lessons we can take from this letter.6

The year prior to the letter’s creation, 1860, saw the election of Abraham Lincoln as president. This set off the secession of Southern states from the Union. The new Lincoln administration was forced to decide whether to let the Union dissolve or rather make war on the Southern states. Immediately upon becoming president, Lincoln declared that since the Union was older than the Constitution, no state could leave it. As a result of this declaration, acts of force or violence to support secession were seen as insurrection. Additionally, he declared that the government would continue to occupy federal property in the seceded states, which was his response to the conflict brewing over Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor.7

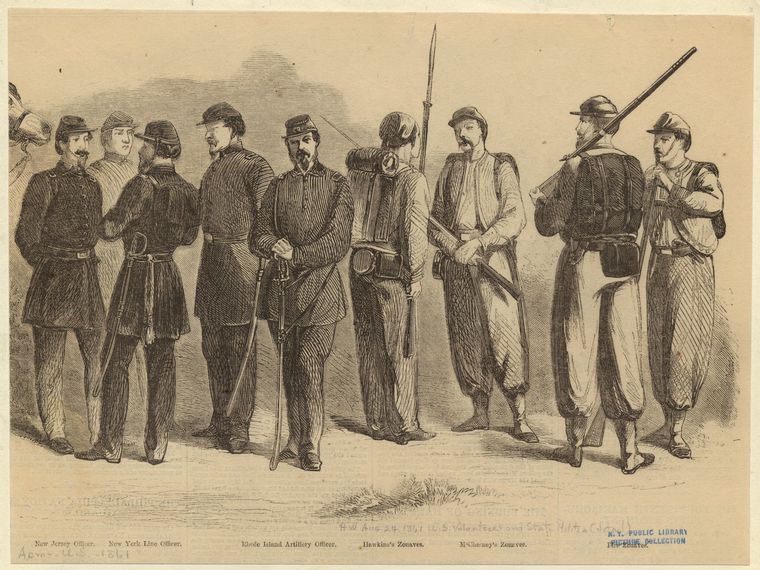

As one Southern state after another declared its secession, Lincoln spoke of American liberty as “a sentiment embodied in the Declaration of Independence,” and began to mobilize the North.8 On May 3, 1861, Lincoln called for an increase of 23,000 troops in the regular army, despite knowing that the majority of the fighting would have to be done by volunteers in state militias, since the Union, much like the Confederacy, had to raise its army from scratch. As the war proceeded, the Union struggled to attract enough volunteers, and Congress was forced to pass a national draft law, which greatly increased volunteer enlistments.7

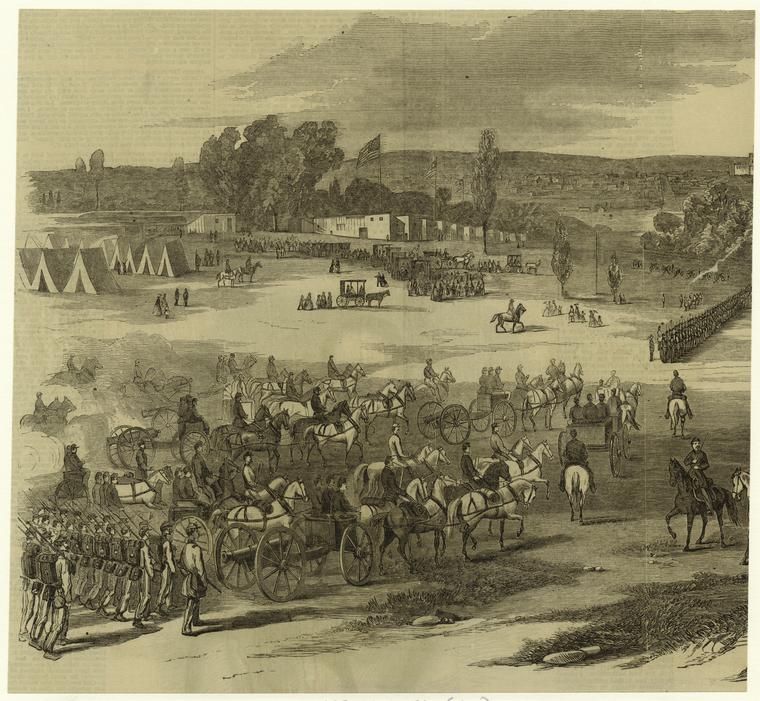

The Battle of Bull Run was the first major battle fought between the Union and the Confederacy in northern Virginia, with the Union army being led by General Irvin McDowell, while the slightly smaller Confederate army was led by General P. G. T. Beauregard. In mid-July, McDowell marched his troops towards Manassas as Beauregard moved his troops behind Bull Run and called for reinforcements, which reached him the day before the battle. On July 21, the battle commenced with the Union initially pushing back the Confederate forces. Just before the Confederate forces could be overcome, they stopped the Union’s last strong assault and began a relentless counterattack, causing the exhausted Union troops to panic and retreat. At this point, McDowell had lost any and all control over his men and was forced to retreat back to Washington D.C. The battle dealt a severe blow to Union morale and to Lincoln’s trust in his officers. Furthermore, this battle disproved the hope that the war would be a short one.10

The political conditions of the war also reflect the social beliefs of the period. It was common for soldiers and civilians to report their hopes and dreams to one another, which helped them overcome barriers of time and space. Most of the time, these dreams centered around the home front, which allowed soldiers to find emotional comfort and psychological healing in a time of great turmoil since thoughts of home evoked a sense of belonging and stability. Moreover, dreams of home allowed soldiers to believe that they were fighting so that their homes would remain safe and their children might sleep in peace.11 In a sense, dreams and letters both functioned in the same way, allowing soldiers to regain a sense of connection with their loved ones from afar. Through Sullivan’s letter, one is able to obtain further insight into the importance of letters and dreams during the Civil War. In Sullivan’s letter, we find these same motives and feelings. It is important to note the audience of the letter, Sarah. In writing to Sarah, Sullivan seeks to find solace and a solution to the dilemma he faces, since he views Sarah as a source of stability. By understanding this deeper level of the motivation behind the creation of the letter, we are able to begin to relate to the emotions that Sullivan and his family were going through. Within the letter, Sullivan expresses desperate despair, longing, and love, emotions that, at some point in life, we have all gone through.

It is also important to understand what “patriotism” meant during the Civil War. While there were many prevailing definitions and aspects of patriotism during this time period, especially depending on whether one was a part of the Union or the Confederacy, Sullivan had a very set definition and understanding of what patriotism meant to him. Sullivan’s idea of patriotism seems to align most closely with the idea that “no true patriot ‘can, in this crisis, stand aloof from the conflict.'”12 This ideal of Sullivan’s understanding of patriotism is reflected in the lines, “a pure love of my country, and of the principles I have often advocated before the people, and the name of honor, that I love more than I fear death,’ have called upon me, and I have obeyed.”13 Essentially Sullivan believed in staying true to the principles laid down in the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution and felt called to action in order to protect these principles and speak for what is right rather than sit passively by. Again, this sentiment is reiterated when Sullivan states, “I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in, the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter.”14 What stands out about Sullivan’s perception of patriotism is he placed full faith in the government and in the cause for which he was fighting. While others did volunteer, they did so primarily out of pride or wanting to show how courageous they truly were. Others opposed having to fight in the war entirely, as seen in the draft riots prior to the start of the war. Yet Sullivan sets all of his own needs aside, as well as his pride and vanity for himself, and instead fights out of love and the hope that his children might have the chance for a better future. In short, Sullivan’s patriotism meant the complete and total giving over of self to a noble cause.

Even though the letter is humble and simple in nature, there is much that we can learn from it. In Sullivan’s letter, one can find the rawest form of human emotion, an intense longing and a sense of deep heartbreak. Through Sullivan’s letter, we gain a true and comprehensive understanding of the intimate ties between a soldier and his loved ones, as well as the immense sacrifice and patriotism that so many soldiers exhibited. The thoughts and feelings discussed within this letter are an invitation for us to consider what love, patriotism, and suffering mean for us in our time. What is so worthy that someone would be so willing to lay down everything that they hold near and dear to their heart? Sullivan’s letter serves to remind us to step back and contemplate the stories of the individuals who have gone before us, and recognize that they were once alive just as we are. Therefore, let us remember the lessons and the lives of people like Sullivan Ballou, people who fought, loved, and hoped just as we still do.

First and foremost, I want to thank Dr. Whitener. I honestly do not think this article would have been possible without his help. With his guidance I have been able to create a new research genre that I hope other scholars will pursue. He truly helped me bring my ideas to life, allowing me to proudly display something that I am passionate about. I would also like to thank my RSC tutor, Franchesca Tinacba, who helped guide me in the early stages of my project proposal and helped me work through the necessary edits to my proposal. One last person I would like to thank is Anacely Murphy, one of the Blume Library research librarians here. Without her help, I am unsure that I would have found the proper sources that were key to providing the framework and foundations of the analysis conducted on Sullivan Ballou’s letter. Overall, I cannot stress enough how grateful I am to each and every person I worked with; without them, I am unsure that I would have been able to produce this article on my own.

- Sullivan Ballou to Sarah Ballou, July 14, 1861, in The Civil War: The First Year told by Those Who Lived It, ed. Brooks D. Simpson et. al. (New York: Library of America, 2011), 452. ↵

- Sullivan Ballou to Sarah Ballou, July 14, 1861, in The Civil War: The First Year told by Those Who Lived It, ed. Brooks D. Simpson, et. al. (New York: Library of America, 2011), 451-453. ↵

- Sullivan Ballou to Sarah Ballou, July 14, 1861, in The Civil War: The First Year told by Those Who Lived It, ed. Brooks D. Simpson et. al. (New York: Library of America, 2011), 452. ↵

- Sullivan Ballou to Sarah Ballou, July 14, 1861, in The Civil War: The First Year told by Those Who Lived It, ed. Brooks Simpson, et. al. (New York: Library of America, 2011), 451-453. ↵

- Sullivan Ballou to Sarah Ballou, July 14, 1861, in Civil War: The First Year told by Those Who Lived It, ed. Brooks D. Simpson et. al. (New York: Library of America, 2011), 452. ↵

- Sullivan Ballou to Sarah Ballou, July 14, 1861, in Civil War: The First Year told by Those Who Lived It, ed. Brooks Simpson, et. al. (New York: Library of America, 2011), 451-453. ↵

- Alan Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past, 15th edition (New York, NY: McGraw Hill, 2014), 365-366. ↵

- Alan Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past, 15th edition (New York, NY: McGraw Hill, 2014), 366. ↵

- Alan Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past, 15th edition (New York, NY: McGraw Hill, 2014), 365-366. ↵

- Alan Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past, 15th edition (New York, NY: McGraw Hill, 2014), 387-388. ↵

- Johnathon W. White et. al., Household War: How Americans Lived and Fought the Civil War (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2020), 77-78. ↵

- J. Matthew Gallman, Defining Duty in the Civil War: Personal Choice, Popular Culture, and the Union Home Front (University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 130. ↵

- Sullivan Ballou to Sarah Ballou, July 14, 1861, in The Civil War: The First Year told by Those Who Lived It, ed. Brooks D. Simpson et. al. (New York: Library of America, 2011), 152. ↵

- Sullivan Ballou to Sarah Ballou, July 14, 1861, in The Civil War: The First Year told by Those Who Lived It, ed. Brooks D. Simpson et. al. (New York: Library of America 2011), 151. ↵

10 comments

Linda Aguilar

This article is interesting and gives insight into the daily struggles of men who love to serve our country but at the cost of their families. The love letters are beautifully written from the perspective of a man who is a patriot and affection for his country supersedes his love for his family. This is a touching love letter to his wife that their love would be the last thing he thinks of upon his death.

Azariel Del Carmen

This is an interesting topic in regards to life during the Civil War through someone that I have never heard of from K-12 or history class here at St. Mary’s. Life in the Civil War was rather harsh for both Confederates and Union soldiers and it was typically common at the time for soldiers to write letters to their families before a battle knowing that they may or may not see the next tomorrow. This article does a decent job in talking about a perspective of the Civil War in regards to those who fought for the greater good of the US itself.

Andy Jordan

That was a beautiful story and deeply moving. It speaks to our world and its troubles today as well. Good analysis of the conflicting emotions felt and very personal decisions. well done!

Linda Hoffman

Analysis is hard work. You successfully examined the internal struggle of a Union officer leaving his wife and family to exercise his duty as a citizen to support the Civil War effort. You made good use of citations that provided compassionate, contextual, relevance to his struggles. Yes, there is a lot such analysis can tell us today. Congratulation on your essay. I hope this achievement might lead you to more writing, and even a book one day.

Michelle Fuentes

Excellent work! It was very well written!

Mary Z Vale

Congratulations! So beautifully written. I am sure that you will accomplish all your dreams!!????❤️

Alan Becker

Very well written. Excellent documented references. Insightful and keen to highlight the larger meaning behind the words in this letter. I thoroughly enjoyed it and learned!!

Andrew Morales

Very well written and interesting perspective on a crucial period of our American history. I hadn’t considered that patriotism had varied motivations but now realize that the term patriotism is a loaded word. This understanding translates to our current state of political affairs where one’s view on what is patriotic may differ. Great article.

Kristen Landry

Excellent work!

Sandy Morales

Really captures the essence of internal human struggles that uncannily are a current dynamic in present day World events.