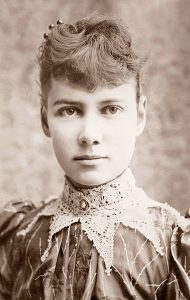

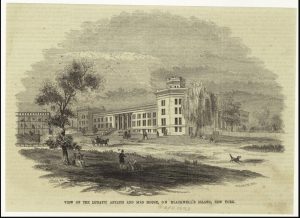

Nellie Bly was a 23-year-old groundbreaking investigative reporter. She went undercover in the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell Island. The paper she worked for had been receiving reports about the asylum, and Bly committed herself there to uncover the truth. She prepared herself by practicing how to appear mentally ill. Blackwell Island, notoriously known for its harsh conditions, loomed ominously in her mind. Despite the dangers, Bly was driven to expose the truth.1

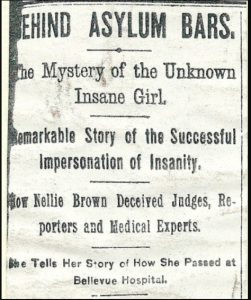

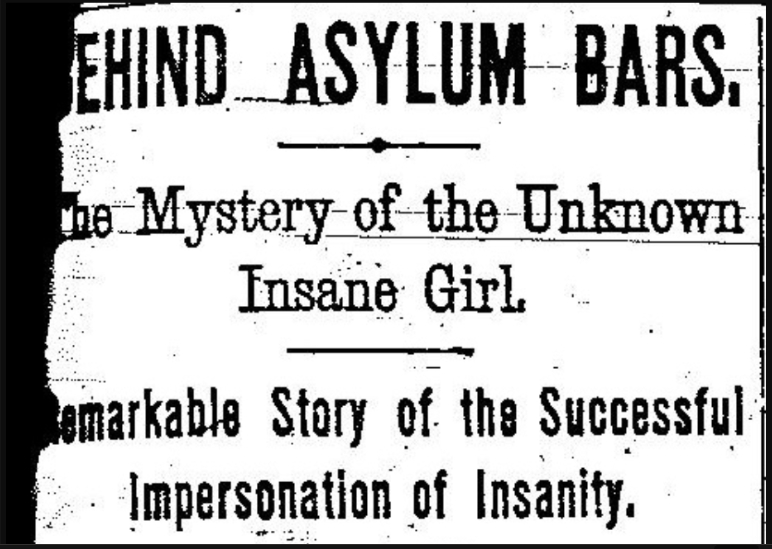

Bly convinced the New York World newspaper to allow her to go undercover at the asylum. She faked insanity by practicing in front of a mirror, widening her eyes and staring off into the distance. She studied how mentally ill patients behaved and mimicked those expressions in the mirror. Nellie arrived at a women’s boarding house for impoverished women and pretended to have amnesia while speaking incoherently. Her odd behavior alarmed the other residents, who reported her to the police. She was then examined to determine the extent of her supposed insanity. One doctor accused Bly of using drugs, which shocked her—but it worked. She was sent to Bellevue Hospital, where she spent several days.2

At Bellevue, Bly underwent several examinations and used the undercover name “Nellie Brown.” She was declared demented and in need of care. In a strange way, she felt a sense of accomplishment—she had successfully made it onto the boat bound for Blackwell Island. As she boarded with other women, one of them warned her, “Blackwell Island, an insane place, where you’ll never get out.”3

Once committed to the infamous asylum, Bly stopped pretending to be insane, but her behavior was still dismissed. The staff, already convinced of her condition, ignored her attempts to explain herself. She quickly realized that once a woman was labeled insane, it was nearly impossible to prove otherwise. The more she insisted on her sanity, the more she was seen as delusional. The institution stripped women of their autonomy and silenced their voices. During her time inside, Bly noticed that many other women were clearly not mentally ill, which further supported her belief that countless sane women were being unjustly institutionalized.4

While analyzing the institution, Bly witnessed horrific living conditions. Patients were forced to share freezing, dirty bathwater, ate spoiled food, and wore thin, tattered clothing. Rats roamed the halls. The nurses were cruel—they beat, mocked, and ignored the women, refusing to listen to their claims of sanity. Bly tried to speak up, but doing so only resulted in harsher treatment.5

Bly began to fear that she might never leave Blackwell’s. Even though she was undercover, she started to lose hope. Seeing so many sane women wrongly committed and brutally treated made her question her ability to escape. Still, she remained committed to uncovering the women’s stories inside the asylum.6

After ten days in the asylum, the New York World arranged for a lawyer to secure her release. This showed how easily someone with outside help could escape, while others remained trapped. Once freed, Bly wasted no time. She wrote a gripping exposé detailing the inhumane treatment and unbearable conditions she had witnessed. Her story quickly spread, sparking a wave of public outrage. The backlash forced New York authorities to launch an official investigation. What they uncovered confirmed Bly’s claims: the asylum was plagued by neglect, cruelty, and a desperate need for reform.7

In the end, Bly’s bravery paid off. Her exposé led to real change. The asylum received $1 million in additional funding, and conditions for the patients improved. More importantly, her story sent a powerful message—that one person, willing to speak up, could spark meaningful reform. Bly didn’t just report on the injustices—she lived them, felt them, and shared them with the world. Her legacy helped reshape mental health care and elevated investigative journalism to new heights. It served as a reminder that one bold voice can ignite lasting change.

- Adrienne Kennedy, “Nellie Bly,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, April 30, 2023), 1. ↵

- Nellie Bly, Ten Days in a Mad-House; or, Nellie Bly’s Experience on Blackwell’s Island. Feigning Insanity in order to reveal Asylum Horrors (New York: L. Munro, Publisher, 1887), 9. ↵

- Bly, Ten Days in a Mad-House, 48–50. ↵

- Tri Fritz, “World Articles (1887–1888) – Nellie Bly Online,” 25. ↵

- Bly, Ten Days in a Mad-House, 58–79. ↵

- Bly, Ten Days in a Mad-House, 79–87. ↵

- Fritz, “World Articles (1887–1888) – Nellie Bly Online,” 26. ↵

26 comments

Mara Kendall

What a remarkable read! I was captivated from the very beginning and didn’t want this story to end. You incredibly painted the scene for your audience. Before reading this story I was unaware of Nellie Bly’s bravery! Thank you Meadow for bringing awareness to her story, her heroism is inspirational.

Alejandro Rubio Chappell

Nellie Bly was only 23 when she made history as a fearless investigative journalist. To uncover the truth about the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell Island, she went undercover, risking everything. After practicing how to appear mentally ill, she was arrested and committed. Her first-hand account exposed horrifying abuse and neglect, leading to real reform and forever changing journalism and mental health care.

Lisa Solis

Truly outstanding work—your research paper was not only thorough and well-crafted, but the topic itself was incredibly intriguing and captured my attention from the very beginning. More importantly, your storytelling sent a powerful message: that one person, willing to speak up, can spark meaningful reform. Bly’s courage in living the story she told helped reshape mental health care and elevated investigative journalism to new heights. Your paper is a moving reminder that one bold voice can ignite lasting change. A well-deserved nomination—congratulations!

Zoe Lozano

Such a well written article! Very interesting.

Yolanda

I really enjoyed reading your story. Never even heard of this until I came across your paper. It was very informative and kept me wanting to know more about this brave lady and how she made a change. Great job Meadow, you did awesome and again thank you for making me aware!

Andrea

Very informative paper, shining light on the history of the injustice of mental health care. A great read!

IRENE

Very informative, congratulations Meadow 🎊

Kayla Ochoa

Shes did a great job.

Maricela A Mendoza

Such a great read, very well written and insightful. Wonderful job!

Benjamin Perez

Great work!

Very good read. Keep up the great work. It will all pay off at the end.