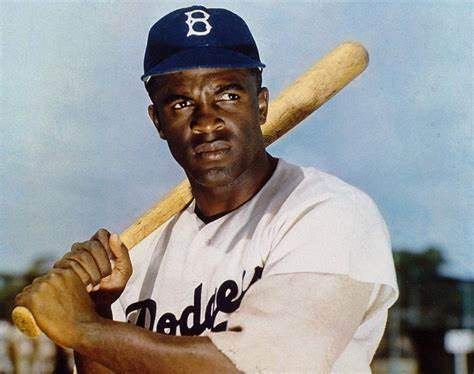

On April 15, 1947, a young man stepped into the batter’s box in his first at bat in a major league game, destined to become one of the most famous yet unlikely civil rights leaders in American history.1

In 1947, the United States, victorious in World War II, still enforced Jim Crow laws. Bigotry ran rampant in insidious and often subtle ways. Major League Baseball (the MLB) began the year segregated, as it had been since the beginning of the twentieth century.2 Still, in some areas outside the South, racism was less prevalent and “in your face.” There, people of all races were beginning to be aware of racial inequities.3

Ten years before Rosa Parks, there was Jackie Robinson. A second lieutenant in the US Army, he refused an order to take a seat at the back of a military bus. For doing so, Jackie faced a court martial, but was subsequently acquitted.4 This was no ordinary year in the life of a man who would go on to become a baseball and civil rights icon.

Branch Rickey, part-owner and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, shook up the MLB world by bringing into the organization the first black player of the twentieth century, Jack (Jackie) Roosevelt Robinson. Jackie Robinson had been a very good (but arguably not the best) player in the Negro leagues when Rickey offered him the job.5

Having been primarily raised in California and educated at UCLA, Jackie was not exposed to the racism and bigotry of the Jim Crow laws of the South, and neither had his new bride, Rachel, who was also raised in California. They never imagined how their lives and the world was about to change because of his unlikely partnership with Branch Rickey. Jackie and Rachel had not been exposed to such treatment, and it was a “tremendous difference” from their prior lives.6

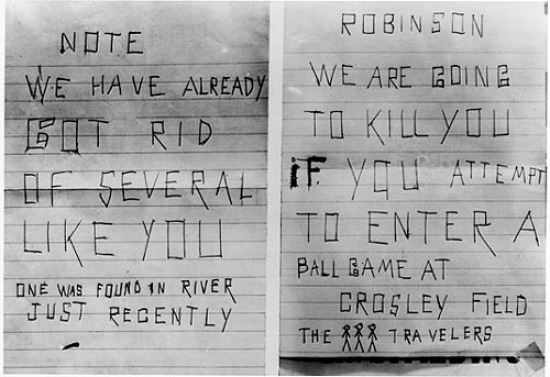

Jackie and Rickey sought to withstand the coming verbal, and sometimes physical, abuse without fighting back, yet without appearing to be weak.7 What would be required of the chosen player would be to play on the starting lineup in order to be a very visible reminder that Major League Baseball was about to change in a big way. The integration of the MLB had to be an apparent, current, on-going event, and not just an abstract concept of the first black player being on the team just sitting in the dugout. The primary focus of both Rickey and Robinson had to be that Jackie be successful on the field. He then must endure the onslaught of racial slurs, bigotry, and dangerous threats to himself and to his family while gaining respect on the baseball diamond.8 For all of these reasons, Jackie Robinson was the choice over all the rest and so began what became a year that would live on in the history of the game of baseball and in no small way, the civil rights movement of the country.

On their way to that first spring training, in Florida, deep in the Jim Crow South, Jackie and Rachel were bumped from two different plane flights for no other reason than for their color.9 “We had to get to that Daytona Beach April 1st. We didn’t have time to be arrested or anything. So we complied and got off, and we decided to take a bus the rest of the way.”10 When they boarded the bus, they were forced to the back. They complied because getting arrested and not meeting their deadline was not an option.11 They made due in horrific conditions, and made their way, the best they could, to spring training.

Once Jackie began playing, he encountered locked gates at ballparks, because the other teams and the communities in the South would not allow “mixed” games with a black player.12 The Sheriff in Stamford, Florida came onto the field and led Jackie away by force, because he was black. The Sheriff was sent there to arrest Robinson if he did not comply. He complied, based on his agreement with Mr. Rickey to not be confrontational.13 Jackie mastered the skill of not being argumentative, yet not appearing to be subservient either. In other words, he complied with dignity and grace.14 This was his lasting legacy, and exactly what he and Mr. Rickey agreed to at the start of the journey.

Rachel recounts how, during those spring training days in the South, the stands were filled with many Black fans who came to see Jackie play. However, the Black fans were not allowed to come through the gates and the turnstiles as the White folks were; they were required to humiliate themselves by stooping to enter through a hole in the outfield fence.15 “When the black section filled up, they had to sit on the field, on the ground.” If a ball came that way, they had to “scramble like animals” to get out of the way of the ball.16 Despite the degradation, the Black fans at the time dressed up in their finest clothes, coats, and hats to attend the ball games.17

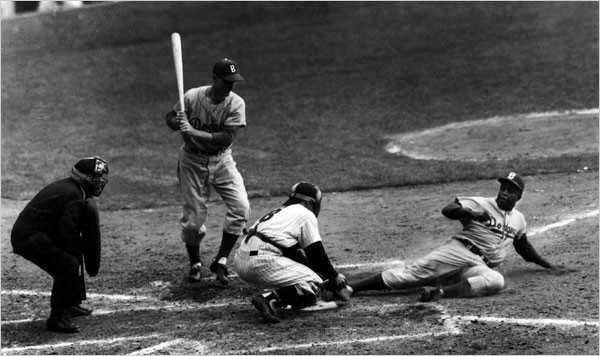

Jackie’s on-field struggles started right off the bat, when he entered a hitting slump that lasted for weeks.18 While this may be a normal adjustment for most players who jump into the MLB from the minor leagues, Rickey’s and Robinson’s plan could not withstand such a slump for long. With everything else that was going on, Jackie had to learn a new fielding position, first base.19 He had been a short-stop in the Negro leagues, and played second base with the minor league Montreal team the year before. The reason this was not possible was the Brooklyn Dodgers of 1947 future Hall of Famer Pee Wee Reese played short-stop, and veteran Ed Stanky played second base, neither of whom was expendable on the Dodgers roster.20 Needing Jackie in the lineup for his batting and base-stealing prowess, Rickey decided that Jackie could learn to play first base, a very different position with a very different skill set. These were some of the many hurdles Jackie had to overcome during that first year in the MLB, both on- and off-field.

As far as the other teams were concerned, Robinson suffered verbal abuse and threats of boycotts (especially from the Manager of the Philadelphia Phillies, Ben Chapman.) When the Dodgers traveled to Philadelphia for their first series with the Phillies in 1947, Chapman called Jackie every foul name he could think of and encouraged his players to do the same. Jackie took it with dignity and grace, and did not acknowledge them.26 Chapman, when asked about the incidents, said that he was only treating Jackie like he treated every other rookie in the league, calling them various degrading names and throwing insults at every opportunity. He said: “We will treat Robinson the same as we do Hank Greenberg of the Pirates, Clint Hartung of the Giants, Joe Garagiola of the Cardinals, Connie Ryan of the Braves, or any other man who is likely to step to the plate and beat us,” and “There is not a man who has come to the big leagues since baseball has been played who has not been ridden.”27 Chapman’s past made these seemingly fair comments ring hollow.

There were instances of violence committed against Jackie on the field by other players. For example, Enos Slaughter, a very experienced player, who was well respected in the league, spiked Jackie at first base late in the season. This was seen as intentional by Slaughter, since it could have been avoided, but also out of character for him as a seasoned veteran of the game. He denied intent to harm Jackie, and no action was taken against him.28 Jackie led the team in “hit by pitch” in 1947. (He was very aggressive in the batters box, standing very close to the plate; however, many pitchers who wanted to show their feelings about the first black player made their feelings known with the high inside pitch.)29 Some players went out of their way to avoid contact with Jackie out of fear of being labeled a bigot or racist. Other players avoided talking to him, out of fear they would be labeled a supporter of integration.30 At that time, the MLB was populated by a very large percentage of players from southern states, and the ones who were not took on the mannerisms, attitudes, and behavior of the southern players. This culture was pervasive in the MLB at the time.31

Some teams threatened to forfeit games against the Dodgers rather than play a “mixed” game with a black player. Rickey, with the backing of the new MLB commissioner, Happy Chandler, said he would gladly take the win, to benefit his team.32 From the 1920’s to 1944 the MLB commissioner was a staunch segregationist, Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis, who likely would not have backed Rickey in his plan with Jackie. Chandler had a much different view and stated his policy was: “If they [black people] can fight and die on Okinawa, Guadalcanal, (and) in the South Pacific, then they can play ball in America.”33 The other teams relented and played. This was the environment into which Jackie Robinson was thrown in 1947.

Then, something miraculous began to happen. Subtle changes began to take shape. Jackie’s hitting slump ended, and he began to hit well. His base stealing slump also ended, and he began to steal bases as before, and at a record pace. His fielding got better, and his teammates, and ultimately other players on other teams, began to respect Jackie for the way he played the game, his quality batting, base running, and aggressiveness.34 The league began to notice that Jackie had withstood all of the abuse, both verbal and physical, without complaint and with dignity and grace. He was not a victim, he was a quality player. Jackie’s batting average, base stealing totals, and other measurable statistics on the field, steadily began to improve and showed his abilities.

Fans noticed and appreciated his talent on the field, and his grace under fire during that first year. During one trip to another city for a game, white fans mobbed Jackie for his autograph, so that he had to have police escort him back to his hotel. Sportswriter Sam Martin said, “it was probably the only day in history that a black man ran from a white mob with love instead of lynching on its mind.”35 White kids were imitating Jackie’s aggressive style of play, and people noticed that too. Toward the end of the season, when the Philadelphia Phillies visited Brooklyn to play another series against the Dodgers, their manager, Ben Chapman, who was so ugly and racist with his insults toward Robinson during their first meeting, sought to make amends, and they met on the field and shook hands in an effort to show there were no hard feelings. For the media, they jointly posed for a picture with a bat.36 The message was that Jackie was part of the MLB and he was there to stay.

The culminating event of Jackie’s acceptance into the MLB, as the first black player, but also as a quality first year player, was the award Rookie of the Year from the MLB.37 This was his crowning achievement to integrate the MLB at long last. The Dodgers ended up in the World Series that year, but lost to the juggernaut New York Yankees, with players as iconic as Yogi Berra and Joe Dimaggio.

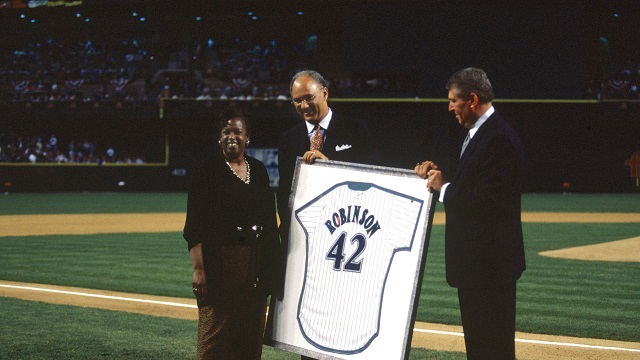

In 1962, Jackie Robinson was inducted into the MLB Hall of Fame on the first ballot.38 Jackie’s number, 42, is the only number to ever be retired by every MLB team. Every year, on April 15, all players in Major League Baseball don jerseys with the number 42 emblazoned on them, all in honor of Jackie and his extraordinary first year in the MLB.39 His example of courage, grace, and dignity during that 1947 year in Baseball, the year Branch Rickey took a chance on a young, black player from the Negro League by the name of Jackie Robinson, forever ending the segregation of Major League Baseball and emblazoned his path as one of a most unlikely civil rights hero.

Jackie Robinson’s first year in Major League Baseball, with the Brooklyn Dodgers, was anything but ordinary.40 The transition from minor league play to major league play would have been difficult enough for anyone. But Jackie faced the unique trial of having to deal with vile, ugly, devastating personal and racial attacks from other teams’ managers and players, the fans watching from the stands, the restaurants and hotels his team visited on the road, and his own teammates. This made the situation almost intolerable. Through it all, he stood strong. Not only did he succeed in the MLB, but he was awarded the Rookie of the Year honor that year. It was not a normal year in the life of a baseball player.41

“The year 1947 has already gone down in baseball history as the year in which Jim Crow was sent packing by professional baseball.”42

- Courtney Smith, Jackie Robinson: A Life in American History (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2021), 113. ↵

- Thomas Zeiler, Jackie Robinson and Race in America (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2014, 5-11. ↵

- Visionary Project, Rachel Robinson: Playing Ball: North and South, 0:17, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Lj_fOIO-NQ, accessed March 30, 2023. ↵

- Courtney Smith, Jackie Robinson: A Life in American History (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2021), 20. ↵

- Jules Tygiel, John Thorn, and John Thorn, “Jackie Robinson’s Signing: The Real Story,” in SABR 50 at 50, ed. John Thorn et al., The Society for American Baseball Research’s Fifty Most Essential Contributions to the Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 162-171. ↵

- Visionary Project, Rachel Robinson: Playing Ball: North and South, 0:19, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Lj_fOIO-NQ, accessed March 30, 2023. ↵

- Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 483. ↵

- Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 55-61. ↵

- Visionary Project, Rachel Robinson: Playing Ball: North and South, 1:45, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Lj_fOIO-NQ, accessed March 30, 2023. ↵

- Visionary Project, Rachel Robinson: Playing Ball: North and South, 3:35, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Lj_fOIO-NQ, accessed March 30, 2023. ↵

- Visionary Project, Rachel Robinson: Playing Ball: North and South, 4:01, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Lj_fOIO-NQ, accessed March 30, 2023. ↵

- Visionary Project, Rachel Robinson: Playing Ball: North and South, 5:02, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Lj_fOIO-NQ, accessed March 30, 2023. ↵

- Visionary Project, Rachel Robinson: Playing Ball: North and South, 5:12, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Lj_fOIO-NQ, accessed March 30, 2023. ↵

- Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 55-61. ↵

- Visionary Project, Rachel Robinson: Playing Ball: North and South, 6:14, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Lj_fOIO-NQ, accessed March 30, 2023. ↵

- Visionary Project, Rachel Robinson: Playing Ball: North and South, 6:53, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Lj_fOIO-NQ, accessed March 30, 2023. ↵

- Visionary Project, Rachel Robinson: Playing Ball: North and South, 6:37, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Lj_fOIO-NQ, accessed March 30, 2023. ↵

- Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 84. ↵

- Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 81. ↵

- Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 67. ↵

- Thomas W. Zeiler, Jackie Robinson and Race in America ( New York: Times Books, 2007), 10. ↵

- Jonathan Eig, Opening Day, The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York City: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007), 199-200. ↵

- Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 81-83. ↵

- Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 673-674. ↵

- Jonathan Eig, Opening Day, The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York City: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007), 190-191. ↵

- Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 84-88. ↵

- Jonathan Eig, Opening Day, The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York City: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007), 151. ↵

- Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 95. ↵

- Jonathan Eig, Opening Day, The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York City: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007), 325, 415. ↵

- Jonathan Eig, Opening Day, The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York City: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007), 202. ↵

- Jonathan Eig, Opening Day, The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York City: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007), 19. ↵

- Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 692-693. ↵

- Happy Chandler, AZQuotes.com, Wind and Fly LTD, 2023, https://www.azquotes.com/quote/1050635, accessed April 12, 2023. ↵

- Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 77-78. ↵

- Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: Putnam, 1972), 78. ↵

- Jonathan Eig, Opening Day, The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York City: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007), 202-203. ↵

- Courtney Smith, Jackie Robinson: A Life in American History (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2021), 148. ↵

- Jonathan Eig, Opening Day, The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York City: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007), 496. ↵

- Thomas Zeiler, Jackie Robinson and Race in America (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2014, 147. ↵

- Jonathan Eig, Opening Day, The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York City: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007), 14. ↵

- Jonathan Eig, Opening Day, The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York City: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007), 14. ↵

- Thomas Zeiler, Jackie Robinson and Race in America (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2014, 99, quoting Henry Foner, “Mah Nishtanah” in Jackie Robinson: Race, Sports, and the American Dream, ed. Joseph Dorinson and Joram Warmund (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E.Sharpe, 1998), 70-71. ↵

75 comments

Gabriella Parra

Jared! You picked such a good topic for an article, and it was very informative. I

Karly West

It is amazing how his life changed because of baseball. The criticism seemed never to faze him, and he won Rookie of the Year because of it. He was inspiring and an amazing role model to the black community and everyone who has faced adversity to keep going. Great article!

Tad York

Great job on your article about Jackie Robinson. I never realized just how much he had to deal with while playing baseball during the years of segregation. I couldn’t have imagined being in his shoes. Thank you for reminding us of just how great he was.

Hunter Stiles

Congrats on the publication of your article!This Jackie Robinson article captivated me from the moment I started reading it. In a really compelling style, Mr. Sherer’s piece conveyed a fantastic narrative. It portrays not just the heroic man’s narrative, but also the era, society, and environment in which it occurred.As events develop, the author draws you into the narrative and spins a tale of Jackie and his family’s heartbreak and victory. The significance of those occasions and the ways in which baseball and America would later be altered are then demonstrated as he leads you through the other side. amazing read.

Guiliana Devora

This was an amazing article and the author did a phenomenal job at telling it. I think that Jackie Robinson was a courageous athlete and not many people could do what he did at his time. For him to be able to do all that he did was incredible and I agree with the author about Jackie Robinson being anything but ordinary.

Jacob Adams

I did not know that Jackie Robinson had grown up in Cali and didn’t experience the racism of the Jim Crow laws. He must have felt very confused when he started being treated this way. Since the league had such a racist culture I wonder why Jackie Robinson even wanted to be in the MLB. Why didn’t he just go back to California? The pictures in this article were great, they were relevant and there were many well cited sources.

Alanna Hernandez

Jackie Robinson is shown more as the token black athlete, which gives his name fame but dehumanizes the rest of his life experiences. This article thankfully gives full context of his life like him being a lieutenant or not having been legally discriminated against as those in the South. congrats on getting such a cool article published this semester.

Luke Rodriguez

This was a fantastic article, and I really enjoyed reading this. I found that the store was very clear to understand. Jackie Robinson was a really well-known baseball player being the first African American to play baseball in an all-white league, and you really showed the horrible things that he went through and the achievements that he had accomplished that made him become a legend.

Marissa Rendon

Excellent article! Congratulations on your nomination for an award! Jackie Robinson was one of the best in tha game. Not only was he the best but he was very respectful. Jackie Robinson experienced many death threats and was thrown in the dirt throughout his career but he remained humble, and ignored the negativity. I really enjoyed the images you used !

Madison Magaro

Jackie Robinson is a name that will always be remembered when it comes to baseball. This article was very well written and provided great information about Robinson. Even though he has treated horribly, he still went out there and made a name for himself. He was a very brave baseball player and this article did a great job at capturing the tough times that he went through.