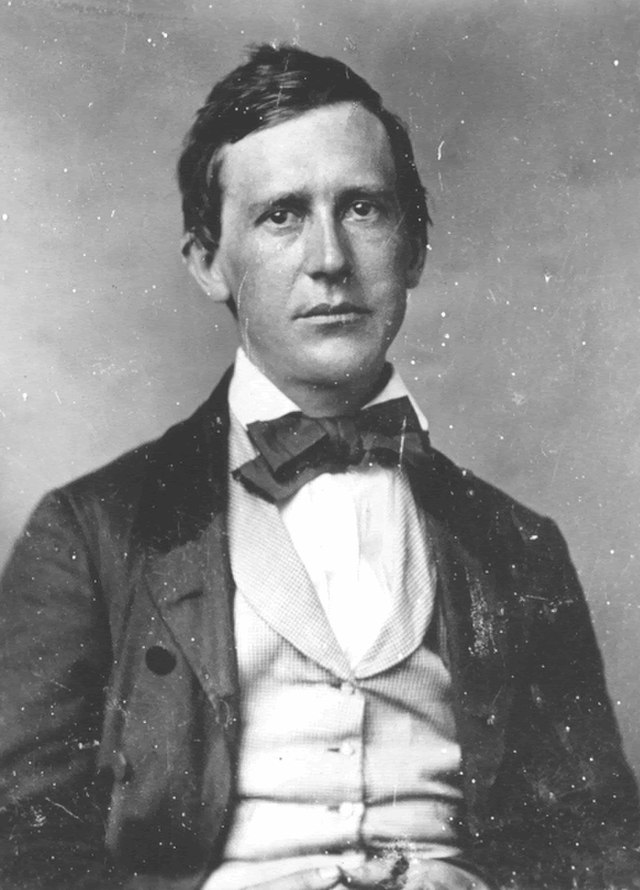

Cincinnati, Ohio: the new home of working musician Stephen Collins Foster. It had been a lifelong dream of his to make a living off of composing music, and now he was living that dream. He knew this would be his life ever since his first taste of success when he published his first song “Open Thy Lattice Love” as a teenager in 1844.1 Since then, he had been working writing minstrel songs depicting simple, foolish blacks. But there’s something different about this place, Cincinnati. There seemed to be words and phrases floating through the air that were new to the musician’s ears. Phrases whispered in the streets about slavery and abolition. Only they weren’t quite whispers, and they weren’t spoken by a mere few. The topic of slavery seemed to be on the lips of every Cincinnati citizen, and read about from every Cincinnati newspaper. What was this new movement opposing slavery?2

It is a strange new world for Stephen Foster, who had grown up in a time and place where slavery was normal and not an institution to be questioned. Slaves had always been obedient to their masters, and whites had always been superior to blacks; at least, that’s what he was raised to believe, having been born into a strongly Democratic family. He had never given the moral issues of slavery a second thought until he had inadvertently thrown himself into a city buzzing with talk on slavery. Slavery was never a thing to be discussed before; he had grown up with a household slave, after all. In fact, it was this very slave that used to take him to black church services, where he was first exposed to and inspired by the negro spirituals that he heard there.3 So slavery had a great impact on his taste and style of music, but for him, there was really nothing more to it. He probably never even connected the dots on the music sensibilities. Slaves were servants. Slaves were property. What more was to be said? Apparently a lot, and Foster was about to find out just how much the country was going to talk about slavery. Maybe even he would chime in, but his views and heart on the matter needed to be changed. Cincinnati was the first step to this happening.4

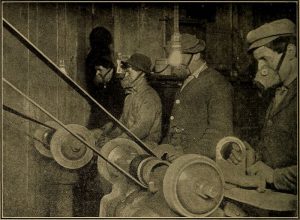

One day in particular, he walked along the wharf where black river workers spent the day unloading heavy cargo just to turn around with even more cargo to load the river boats with. He watched them as they worked on the steamboats and was impressed by their physical strength doing jobs that were available to them because they were deemed as undesirable and no one else wanted them. Mark Twain had once described them as “no pitiful handful of deckhands, firemen, and roustabouts, but a whole battalion of men.”5 Men. These were not just creatures of work, but fellow human beings. This was perhaps the first time, in his heart, Stephen Foster could see the black population as such. Those men working on the wharf had dreams and feelings just like white men. They had families. They had faith in God. These were all things Foster, as an individual, could relate to them with. On a more specific, personal level, both sang songs and attached meaning to music. He watched from a distance astounded by the sounds of their deep, full voices as they worked. He stood there observing how they interacted and worked. Yes, these were not just workers; they were men with individual feeling and soul.6

Recognizing the black man as a man for the first time opened Foster’s heart to seeing the person, but he would need to open up further if he was to attach himself to this so-called antislavery movement that was so popular in his city. This is where Charles Shiras entered his life, or rather, reenters his life. Foster had grown up with Charles Shiras, who was one of his closest friends and neighbor from boyhood. Shiras was known as a reformer and antislavery advocate. He owned his own newspaper, the Albatross, which featured his own poetry championing the oppressed, both black and white. Poetry really connected the two old friends, and the two spent countless long evenings writing and discussing slavery. Shiras clearly had strong beliefs on the subject, and heavily influenced Foster who was just like a sponge absorbing all these new ideas of abolition and the potential society that respected the lives and rights of all its citizens, no matter the race. It was this friendship and collaboration that marked a shift in Foster’s own songwriting. Minstrel songs were what he attributed his living to.7 Songs that were used in minstrel shows intended to entertain white audiences. These songs usually portrayed their black protagonists as simple-minded fools. It was what sold, and Foster had never had issues with it before. Now his worldview was changing, and so did the content of his songs. He found himself writing lyrics that urged listeners to sympathize with the humanity of the slave. These new songs sought the tears and sympathy of its white audiences to feel for the black protagonist.1

As his songs reflected a growing sentiment of sympathy, so did he personally grow more and more sympathetic toward the antislavery mission. Why, just a few blocks away from where he lived was the newly established Mission Church. Its three stories of brick protected the spirit and culture of African Americans, and maybe kept more than just their spirit alive. Rumor had it that the basement was a stop in the underground railroad, leading slaves to the safe clutches of freedom. On hot summer days the windows were propped open, allowing the voices of their African spirituals to be heard by all passing by. Foster often walked by, given its convenient proximity, taking in the lush sounds of the choirs of spirituals. Frederic Douglas described their slave songs saying that “the mere hearing of those songs would do more to express some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do.”9 He heard sounds that were reminiscent of his childhood when he would hear African spirituals from the church his family slave brought him, or the songs of day laborers working tirelessly. This was truly a strong people who had been dealt an unhappy hand. Foster now felt that slavery was “an intolerable burden under which the black race stumbled helplessly and hopelessly.” Certainly he had come a long way from writing songs that mocked the race.10

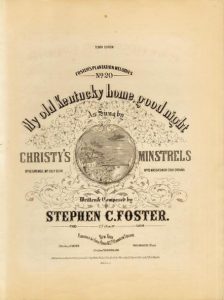

Stephen Foster had come a long way from growing up around the normal reality of slavery, to changing his style of lyric writing entirely, which had gained him a living as a musician. For years he had been living his lifelong dream: making a living as a professional musician. He found real success in contracted writing for Christy’s Minstrels, most of his songs taking place in the setting of the southern states of the United States.1 Funny enough, he had never actually seen the picturesque settings he wrote of in his songs. This he was going to change right away. He embarked on a trip with family members to see the south. Along each southern port, he saw something shocking. Out in the fields and on plantations he saw back-breaking work being done by the slaves. He had seen slavery in the north of course, but nothing could have prepared him for the terrible treatment and suffering he witnessed in the South. Men and women working in the fields, picking cotton from sunrise to sundown. This was not right. He had to do more, and he needed to find out more. So he turned to Harriett Beecher Stowe. Just a few months earlier, Harriett Beecher Stowe published to the public her novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. This antislavery novel was truly sweeping the nation; everyone was talking about it. Her characters moved Foster so much that upon returning home, he actually sat down to write a song based on it. He wrote one of his most famous and moving songs, “My Old Kentucky Home,” basing its characters on Stowe’s novel. Although his own manuscripts beheld original lyrics “Poor Uncle Tom, Good Night,” he opted to change them to make them more universally appealing.12 He crafted the theme of “My Old Kentucky Home” to be about the separation of loved ones, finding himself especially saddened by the separation the slave system caused families. His heart had gone through a significant change, and his song was his subtle contribution to the antislavery movement.13

Oh weep no more, my lady,

Oh weep no more today!

We will sing one song for the Old Kentucky Home,

for the Old Kentucky Home, far away.

Stephen Foster never openly committed to being in support of the antislavery movement. His family was strongly democrat and would have disapproved terribly. He probably would have lost a large portion of his southern audience in openly supporting the cause. Even so, his change of heart was reflected in his music. A composer who had for a long time made a living off of mocking the black population, was now subtly trying to change the way his audiences viewed them by writing sympathetic lyrics, urging their humanity to be seen. He couldn’t directly end slavery altogether, but just maybe his songs would reach the ears and hearts of a nation.14

- “Stephen Foster,” in The Faber Companion to 20th Century Popular Music, by Phil Hardy. 3rd ed. (Faber and Faber Ltd, 2001), https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/ffcpop/stephen_foster/0. ↵

- JoAnne O’Connell, The Life and Songs of Stephen Foster : A Revealing Portrait of the Forgotten Man Behind ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Beautiful Dreamer,’ and ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016), 149. ↵

- “Foster, Stephen (Collins),” in Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, 2017, https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/ebconcise/foster_stephen_collins/0 . ↵

- JoAnne O’Connell, The Life and Songs of Stephen Foster : A Revealing Portrait of the Forgotten Man Behind ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Beautiful Dreamer,’ and ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016), 103-116. ↵

- JoAnne O’Connell, The Life and Songs of Stephen Foster : A Revealing Portrait of the Forgotten Man Behind ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Beautiful Dreamer,’ and ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016), 106. ↵

- JoAnne O’Connell, The Life and Songs of Stephen Foster : A Revealing Portrait of the Forgotten Man Behind ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Beautiful Dreamer,’ and ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016), 103-108. ↵

- JoAnne O’Connell, The Life and Songs of Stephen Foster : A Revealing Portrait of the Forgotten Man Behind ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Beautiful Dreamer,’ and ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016), 149-150. ↵

- “Stephen Foster,” in The Faber Companion to 20th Century Popular Music, by Phil Hardy. 3rd ed. (Faber and Faber Ltd, 2001), https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/ffcpop/stephen_foster/0. ↵

- JoAnne O’Connell, The Life and Songs of Stephen Foster : A Revealing Portrait of the Forgotten Man Behind ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Beautiful Dreamer,’ and ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016), 152. ↵

- JoAnne O’Connell, The Life and Songs of Stephen Foster : A Revealing Portrait of the Forgotten Man Behind ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Beautiful Dreamer,’ and ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016), 149-170. ↵

- “Stephen Foster,” in The Faber Companion to 20th Century Popular Music, by Phil Hardy. 3rd ed. (Faber and Faber Ltd, 2001), https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/ffcpop/stephen_foster/0. ↵

- “My Old Kentucky Home (1898)—Edison Male Quartet (written by Stephen Foster),” in Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings, by Steve Sullivan (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2013), https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/rowmanpopular/my_old_kentucky_home_1898_edison_male_quartet_written_by_stephen_foster/0. ↵

- JoAnne O’Connell, The Life and Songs of Stephen Foster : A Revealing Portrait of the Forgotten Man Behind ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Beautiful Dreamer,’ and ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016), 162. ↵

- JoAnne O’Connell, The Life and Songs of Stephen Foster : A Revealing Portrait of the Forgotten Man Behind ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Beautiful Dreamer,’ and ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016), 161. ↵

5 comments

Abbey Stiffler

Foster’s shift of attitude toward black slaves following a typical interaction with them intrigues me. Despite his family’s blatantly democratic heritage, he truly took it upon himself to educate himself about the existence of slavery and the antislavery cause. This article just shows how important and influential music can be. It shows how people can change their point of view and how you do not have to be stuck with te same views your family might have.

Gabriella Parra

This is an amazing story! It’s amazing that Stephen Foster’s opinions changed so drastically over the course of his life. At first, he was probably only doing what was traditional and profitable by writing minstrel songs. Later, he really took it upon himself to educate himself on the institution of slavery and the abolition movement despite his family’s stark democrat roots.

Karly West

I think this article perfectly illustrates the way that media and specifically music can affect public opinion. Foster is a great example of this. Undoing years of racism are hard work, usually, these views are backed by years and years of generational views. It’s amazing that communication and understanding are all it took to see that were all the same. Beautiful story, good job!

Danielle Rangel

This article is an amazing way to demonstrate how music can change and portray people’s perspectives. I think it is interesting how Foster changes his perspective of black slaves after a normal encounter with them. I believe music is a form of communication that allows deeper meaning than words or sentences alone could ever have! Through this article and Foster’s experience, the importance of music and perspectives is demonstrated in the story of Stephen Collins Foster and through his music.

Danielle Sanchez

This article was very well written and insightful. This article really touches base not only on racism but how it is possible for people to change their perception. The article states how Stephen Foster was raised with the ideology that slavery was normal and that people of color were simply property of the white man. Learning that these people are more than mere laborers they share the same beliefs as their masters have.