Few of those who are passionate about history have dedicated as many years to a single project as Charlotte Kahl. Many find interest in a topic, and they research and write about it, and then they move on. I had the pleasure of interviewing a historian who breaks this mold. Charlotte Kahl has dedicated decades of her life to researching the Old Spanish Trail auto highway. From the time of its construction, the Old Spanish Trail organization kept records related to the highway’s construction, but it wasn’t until 2002 that an organization formed to research and conserve the auto route. That year, enthusiasts founded the Old Spanish Trail Centennial organization to preserve the history of the highway and organize a series of historical reenactments that would culminate in a grand motorcade across the Old Spanish Trail in 2029.1 Their efforts resulted in a number of emerging historians and conservationists joining in this preservation project. Of them, Charlotte Kahl emerged as the chosen candidate to lead the organization. Kahl’s determination, devotion and commitment to the Old Spanish Trail Centennial organization have helped recover histories lost for nearly a century.

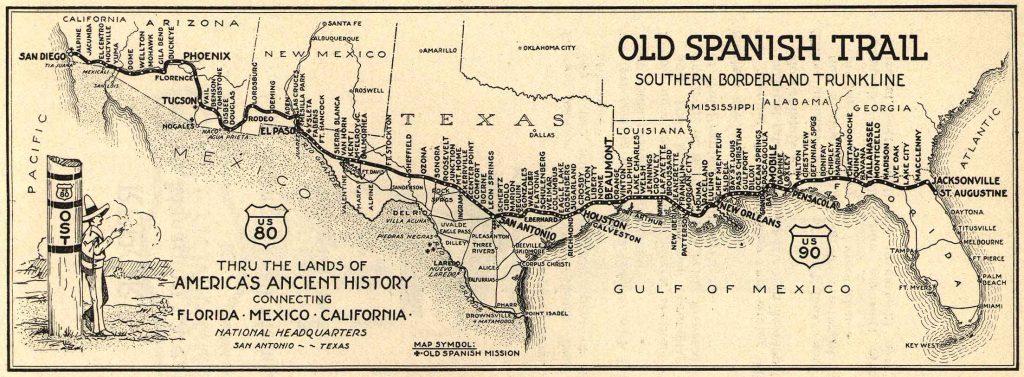

These histories Kahl uncovered are of the Old Spanish Trail, a highway constructed in the 1920s linking the Atlantic and Pacific seaboards of the United States. From St. Augustine, Florida to San Diego, California, the Old Spanish Trail was one of the first true interstate highways in the United States.2 Even more remarkable, the Old Spanish Trail was entirely financed by local governments and business owners. The highway connected six important cultural centers of the American south. The Old Spanish Trail aimed to bolster the tourism industry and foster growth in local businesses as people took the scenic route across the southern belt of the United States.3 Despite its lack of uniform construction materials, the Old Spanish Trail was considered at the time to be the fastest highway to travel on throughout the year. The efficiency of regionally financed roads developed interest throughout the early 1920s, as investors and local boosters saw the commercial potential of such a road passing through, rather than around, their towns.4

The original Old Spanish Trail organization grew quickly and received a great deal of support from local businesses and politicians, who were eager to profit from the collaborative project. Even before the highways were finished, the Old Spanish Trail organization distributed documents they called ‘Travel Logs” to build public interest in the highway. These travel logs provided valuable information for tourists about places they could expect to visit while traveling along this road. More practically, they served as a brilliant marketing tool for the highway, as businesses that likely received little exposure in the press could now potentially gain business from tourists passing through their area.5

Aside from the benefits to local businesses, President Calvin Coolidge and the United States War Department recognized the Old Spanish Trail as a national highway in 1923 due to its potential military benefits as “an essential element of United States defense.”6 General John Pershing placed the Old Spanish Trail on the United States Military Route Map in 1922, which ensured that the highway would receive the support necessary for its upkeep, at least for the time being. The Old Spanish Trail became the necessary link between military sites in the United States, in part because the Great Depression halted highway construction after 1929.7 The United States in the 1920s had no integrated highway system, and railways and poorly constructed, narrow roads were the primary means of transportation.8 Amidst such poor conditions, the Old Spanish Trail became a vital lifeline across the United States, a nation suffocated by economic depression.

In the 1950s, regionally financed superhighways that demanded tolls were standard. As a result, regionally operated highways such as the Old Spanish Trail were a novelty, as they were generally single or dual lane roads intended for both local and regional traffic that were free to drive on.9 The first official legislation that granted significant federal funding for highway construction in the United States was in 1954. At the time, Eisenhower preferred the expansion of the already burgeoning network of toll roads across the United States as a way to have road construction pay for itself. This critical importance to both the nation’s national security and as a precursor of modern highways has often been overlooked by historians who consider the 1950s as the critical years of highway development in the United States. In 1956, $27 billion was allotted to a new federal highway system. The United States’ government recognized that the toll-based superhighways limited the amount of traffic between disparate regions of the United States, and therefore the potential commercial benefits. Their idea was to construct a network of interstate highways that were accessible free of charge to the public, a quality that had made the Old Spanish Trail unique and valuable in the past. This in turn would promote internal commerce within the United States. The economic potential of the proposal was too alluring to overlook, and Congress shortly approve the proposed highway legislation. The bill committed that the federal government would cover 90% of the construction and maintenance costs of these roads.10 Congress raised taxes on certain goods vital for highway transportation such as tires and gasoline, and the construction of the federal highway systems began.

The Old Spanish Trail stands as example of an important precedent to this shift in highway policy. Whereas highways before the 1956 federal allotment were toll-based superhighways, the Old Spanish Trail was an open-access roadway. Though the highway was regionally operated, Pershing recognized the Old Spanish Trail’s value in terms of accessibility and as a conduit between military installations in the United States. In this way, the Old Spanish Trail was a regionally operated and federally recognized highway of critical importance to those who couldn’t afford to play highway tolls and was an asset to the United States’ military. The unique history of the highway makes it a valuable artifact of a transitional period of American history. And thus, it drew the attention of a hobbyist and emerging historian who would eventually become its greatest advocate — Charlotte Kahl.11

Kahl was born in Troy, Ohio. Her father created propellers for military aircraft during World War II, and her mother owned her own public relations firm. Kahl would discover later in her life that her parents’ professions and influences led her into historical studies decades later.

After finishing primary school, Kahl studied biology at the University of Dayton in Ohio. Kahl’s high school teachers heavily influenced her choice of major. Kahl had “a very dynamic biology teacher … and a very boring history teacher.” After two and a half years, Kahl left school to focus on raising her children. Her time at home and her conversations with her husband during this time developed a budding interest in genealogy, which led her into the field of history. Soon after developing this interest in genealogy and conducting research, Kahl began to travel along highways 80 and 90, the two modern highways that run along the Old Spanish Trail. During the course of Kahl’s travels, she built a relationship with Bexar County officials involved in conservation and began to travel across the Old Spanish Trail on a regular basis and gaining an intimate knowledge of the towns along the two highways.12

Kahl’s public relations skills and boundless energy were her greatest tools for conducting historical research. Kahl attributed these traits to her parents. After World War II, Kahl’s father translated his skills as a propeller mechanic to washing machines, and her mother taught her valuable social skills gained through years of running a public relations firm. Kahl found yet more support in her husband, who was also in public relations. From the time of Kahl’s first involvement with the Old Spanish Trail, her husband has collaborated with her on projects and proofread all of her press statements.13

A lack of formal education in the field of history has never limited Kahl. The enormous support network she has at her disposal is complimented by her energy to travel across the Old Spanish Trail throughout the year. Kahl possesses insatiable desire to learn about the stories of locals she encounters. On Kahl’s first journey across the Old Spanish Trail, she focused her efforts on gathering oral histories and photographs. Kahl reached out to the heirs of family owned businesses and homes, who often could share historical accounts of events that occurred on the Old Spanish Trail. Many also spoke of the dangers of gentrification in their area. Local governments threatened local businesses, homes and even bridges with demolition. Whereas local officials may consider an old rusty bridge unsightly and simply wish to “tear [it] down and build a new concrete one straight across,” Kahl has worked with residents in dozens of towns to persuade the local government to renovate rather than destroy these historic landmarks.14 As recognition for Kahl’s conservation efforts, the San Antonio Conservation Society awarded her the Historic Preservation Award for the Built Environment in 2006.15

As chairwoman for the Old Spanish Trail Centennial organization, Kahl’s efforts in conservation and outreach are made with a specific goal in mind. In 2029, after a decade of celebrations along the Old Spanish Trail, a massive motorcade is being planned to honor and publicize the highway. Kahl reached out to multiple conservation societies and historic societies. In the process, she forged valuable partnerships with the San Antonio Office of Historic Preservation, the American Volkssport Association and the San Antonio Transportation Museum. These connections are all vital to the success of the centennial celebration, as all focus on the conservation and beautification of the Old Spanish Trail route.16 Kahl’s projects on the Old Spanish Trail have been met mostly with success, and she has valuable advice for aspiring historians.

To Charlotte Kahl, the most important aspect for new professionals in the field of history is to ask questions. Kahl shared an analogy with me to illustrate her point. When she was a child, Kahl would stare out the window when she went on road trips with her parents. Today, as she travels across the country, she sees more eyes focused on phones than on the scenery. Kahl’s point is that without observation and interest, there is a lack of inquiry and therefore information. Interest alone isn’t enough. For those interested in history, for those who want to affect change, and for those who simply want to learn more, the path is the same. Charlotte Kahl’s mantra when being asked about this subject was simple. Kahl simply said to “get your boots on the ground.”17 It sounds simple enough, but historians today need to engage and collaborate with the community, not inform them from the isolation of an archive. Charlotte Kahl is what the modern historian needs to be in an era rich with collaborative opportunities and a revitalized interest in local history.

- “Old Spanish Trail Basic History,” OST100. Accessed May 6, 2019. http://www.oldspanishtrailcentennial.com/history/Old%20Spanish%20Trail%20Basic%20History.pdf. ↵

- “Three States Claim First Interstate Highway,” Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology, Accessed May 6, 2019. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/96summer/p96su18.cfm. ↵

- “Old Spanish Trail Basic History,” OST100. Accessed May 6, 2019. http://www.oldspanishtrailcentennial.com/history/Old%20Spanish%20Trail%20Basic%20History.pdf. ↵

- Patty Machelor, “The First Old Spanish Trail,” Arizona Daily Star, December 15, 2005. Accessed May 6, 2019, http://www.oldspanishtrailcentennial.com/articles/The%20first%20Old%20Spanish%20Trail.pdf. ↵

- “Travel Information, Page 2, Libirty, Dayon, Crosby, Houston,” OST100, accessed May 6, 2019, http://www.oldspanishtrailcentennial.com/travel_log/1923-1/TI-Page-2.jpg. ↵

- “Old Spanish Trail Basic History,” OST100. Accessed May 6, 2019. http://www.oldspanishtrailcentennial.com/history/Old%20Spanish%20Trail%20Basic%20History.pdf. ↵

- “Military Aspect of the Old Spanish Trail,” OST100. Accessed May 6, 2019, http://www.oldspanishtrailcentennial.com/history/MILITARY%20ASPECT%20OF%20THE%20OLD%20SPANISH%20TRAIL.pdf. ↵

- Elisheva Blas, “The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways: The Road To Success?” (Ramaz Upper School, New York City: 2010), 128-129. ↵

- Elisheva Blas, “The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways: The Road To Success?” (Ramaz Upper School, New York City: 2010), 126-129. ↵

- Gary T. Schwartz, “Urban Freeways and the Interstate System,” Southern California Law Review, (1976): 186. ↵

- “Military Aspect of the Old Spanish Trail,” OST100. Accessed May 6, 2019, http://www.oldspanishtrailcentennial.com/history/MILITARY%20ASPECT%20OF%20THE%20OLD%20SPANISH%20TRAIL.pdf. ↵

- Charlotte Kahl, “Charlotte Kahl and the Old Spanish Trail,” Interview by Gabriel Cohen and Scott Sleeter, March 11, 2019. ↵

- Charlotte Kahl, “Charlotte Kahl and the Old Spanish Trail,” Interview by Gabriel Cohen and Scott Sleeter, March 11, 2019. ↵

- Charlotte Kahl, “Charlotte Kahl and the Old Spanish Trail,” Interview by Gabriel Cohen and Scott Sleeter, March 11, 2019. ↵

- “Conservation Society Giving Two Special Honors This Year,” MySA.com, Accessed May 6, 2019, http://www.oldspanishtrailcentennial.com/articles/Conservation%20Society%20giving%20two%20special%20honors%20this%20year.pdf. ↵

- “Promote,” OST100, Accessed May 6, 2019, http://www.oldspanishtrailcentennial.com/articles.html. ↵

- Charlotte Kahl, “Charlotte Kahl and the Old Spanish Trail,” Interview by Gabriel Cohen and Scott Sleeter, March 11, 2019. ↵

4 comments

Malleigh Ebel

I found the interview information very interesting. Kahl was very proud of her accomplishments and one of my favorites was getting General John Pershing to put the Old Spanish Trail on the United States Military Route Map in 1922. Kahl’s ability to do so much without much formal education is inspiring, and her use of oral history across the communities along the Old Spanish Trail was truly amazing.

Sydney Hardeman

This was a very we’ll-written, interesting article. It is cool how Kahl’s story as a historian began with her parents’ past, and how she was very in touch with the things around her as she went along her journey. As mentioned at the end of the article, it is important to ask questions, which is exactly what she did. It was very difficult to discover new things without asking questions and forming relationships.

Kristina Tijerina

After reading this article, the best thing I learned was that we need to be more observant and ask more questions instead of attaching our eyes to our phones. Kahl uncovered different histories of the Old Spanish Trail, built relationships with Bexar county officials, and began traveling the Old Spanish Trail in order to gain more knowledge through observations. Now, the Old Spanish Trail Centennial ensures that preservation of the trail remains and organizes historical reenactments across the trail.

Victoria Davis

Once again it shows another successful lady from our paving the way for women to stand up and not fear intimidation from the world. She took pride in conserving and keeping the route beautified. It also really shows how highway construction was formed through the Old Spanish Trail. How important it was for military use back then and how the economic perspective was built.