On Thursday, January 12, 1893, Queen Liliʻuokalani successfully lobbied the Hawaiian Legislature to vote out the current cabinet of ministers, allowing her to appoint new ministers who would assist her in establishing a new constitution for the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. It was a powerplay of the highest drama, with the future of the kingdom at stake. Liliʻuokalani had friends who shared her beliefs of a Hawaiʻi free of foreign control. Because of this, she created enemies who had very different plans for the future of Hawaiʻi. The future of Hawai’i now lay in the events that would unfold in the next few days. How did the Queen, and Hawai’i, get to this point? To fully understand, we must look back to the first domino to fall in this drama, to the date of Hawai’i’s independence in 1843.

Hawaiʻi was first recognized for its independence in 1843, with the United States, Italy, and Great Britain recognizing the islands. The Hawaiian Kingdom was led by the Kamehameha dynasty until 1874, when David Kālakaua, also known as the “Merrie Monarch,” took over as king of the Hawaiian Kingdom at a time of change in Hawaiʻi, with many foreign businessmen and sugarcane farmers coming to take land from the Hawaiians. Even though Kālakaua tried to fight against the foreigners, Hawaiʻi sugar planters’ desires to maintain access to profitable U.S. sugar markets converged with U.S. federal and military leaders’ interests in maintaining the Hawaiian Islands as a military outpost. The United States and Hawaiʻi entered into treaties allowing for the duty-free import of Hawaiian agricultural products. As a result, sugar plantations that had been near bankruptcy became lucrative. However, the businessmen located in Hawaiʻi wanted to have more control and power over the islands, especially over the trade system. This caused the United States to eventually demand control of Pearl Harbor in order for it to renew this treaty.1 The politician Lorrin A. Thurston, whose ancestors included some of Hawaii’s first missionaries, helped create a volunteer militia to defend the interests of the foreigners. On July 6, 1887, he stationed 150 uniformed militiamen with fixed bayonets near the palace while coercing the king to sign what became known as the “Bayonet Constitution.” This constitution allowed the king to keep the throne, but it made him share power with the legislature and his ministers. He had no role in amending the constitution, and he couldn’t fire members of the cabinet. King Kālakaua signed the Constitution under duress, showing his love for the Hawaiians, choosing their safety over the safety of the monarchy.2

After King Kālakaua died in 1891, his sister Liliʻuokalanai became Queen on January 29, 1891. One of her main objectives as Queen was to find a way to abolish the Bayonet Constitution. Liliʻuokalani had realized how the constitution heavily favored foreigners, and she wanted to fix it in order for Hawaiians and foreigners to have equal rights. She sought to abrogate the Bayonet Constitution, in part because she wanted to appoint her own cabinet ministers. So, after much planning, on January 12, 1893, Liliʻuokalani successfully lobbied the legislature to vote out the foreign-empowered cabinet, allowing her to appoint ministers who shared her way of thinking. On Saturday, January 14, she declared the legislative session closed, and then summoned her new cabinet to a meeting at the palace, expecting them to sign a new constitution. Coached by Lorrin Thurston, they refused, claiming—quite correctly—that she was asking them to disobey current law. She furiously argued with them, but in the end, was forced to admit she had overreached. She backed down, not wanting to give the foreign warships in the harbor any excuse to intervene.3

This meeting with Queen Liliʻuokalani and her cabinet led to the creation of the Committee of Safety. One of the main figures in the Committee of Safety was Lorrin A. Thurston. Thurston had been kicked out of the cabinet during Kālakauaʻs reign, but he still held political influence. He, along with the other thirteen members of the Committee of Safety, decided to denounce the queen on January 16, 1893, just a few blocks away from the palace, thanks to the help of John L. Stevens, who at the time was the U.S. Minister to Hawaiʻi. The Committee of Safety sent a letter to Minister Stevens, saying they were unable to protect themselves and needed help from the United States.4 After receiving this letter, John L. Stevens believed that the “Hawaiian pear was now fully ripe, and this was the golden hour for the United States to pluck it,” showing just how greedy John L. Steven and the businessmen were in wanting to take over Hawai’i. Following his orders, the USS Boston was dispatched to Hawaiʻi.5

When it landed in Honolulu Harbor, it dismounted 162 marines and sailors. They were ordered to protect U.S. assets around ʻIolani Palace. As historian Paul Rutz writes of the event, “Thurston worked through the night writing a justification for the overthrow, while other members of the Committee of Safety asked Sanford B. Dole, a justice on Hawaiʻi’s Supreme Court, to act as president,” a position which he accepted on the morning of January 17.6 Liliʻuokalani was made aware of their arrival, and had armed men estimated to be twice the size of the American troops to counter them. While Liliʻuokalani could have easily forced the marines to retreat, she thought of her people first and of Hawaiians’ recent past with “armed occupation.”7 She wanted to try and settle this in a peaceful manner, so as not to legitimize the overthrow attempt.8

On January 17, 1893, the Committee of Safety requested Liliʻuokalani to disarm her royal guards or face the threat of harm against her people. Queen Liliʻuokalani, fearful of the potential bloodshed that could occur between the Hawaiians and the Committee of Safety, yielded her authority. What was more important, however, was that Liliʻuokalani issued a statement saying that she would be giving authority to the United States government rather than the Provisional Government, with Lili’uokalani saying “I yield to the superior force of the United States of America, whose minister plenipotentiary, his excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the said Provisional Government,” which showed that Lili’uokalani did not believe that the Provisional Government was fit to rule over Hawai’i. This meant that Liliʻuokalani was not ceding Hawaiian sovereignty or independence to the Committee of Safety, but was handing over executive power to the United States until the overthrow was revoked.9 Because of this, Sanford B. Dole became President of the Provisional Government of Hawai’i, and Liliʻuokalani was placed under house arrest in Washington Place. The fate of Hawaiʻi was now in the hands of Grover Cleveland and his actions.

Grover Cleveland was the 22nd and the 24th president of the United States, and was in favor of letting Hawaiʻi remain an independent kingdom. This was in contrast to his predecessor Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd president. While Harrison was not viewed as an expansionist, some of his actions during his last couple of months in office made it seem as though he had an expansionist mindset. An example of this occurred in 1892. His secretaries James G. Blaine, Benjamin Tracy, and John L. Stevens had tried to convince him to annex Hawaiʻi with no success. This changed on January 28, 1893, when he heard about the Hawaiian overthrow. This caused him to write up a treaty of annexation on February 4, which he finished on February 15; he sent it to the Senate for confirmation. Harrison negotiated the treaty quickly, and was clearly on a path to empire. This confused many people, mostly due to the fact that Harrison was not viewed as an expansionist and was very cautious, who before writing the treaty would take steps to prepare public opinion for a change in the Hawaiian situation.10 Thankfully, Grover Cleveland withdrew the treaty, and instead sent James Blount to investigate the United States’ involvement in the Hawaiian Kingdom’s overthrow. Blount composed a report named after him in July of 1893, talking about the United States’ involvement during the events of the overthrow.

Blount found that the overthrow could not have succeeded without the actions of the United States military forces. He sent his report back to Grover Cleveland, who in November gave Liliʻuokalani a deal to pardon those who had overthrown her, allowing the United States to restore the monarchy. However, Lili’uokalani refused, saying that the Committee of Safety needed to be punished for their crimes. After seeing that there was no changing his mind, Lili’uokalani tried to accept the deal, but it was already sent to the Senate and the House of Representatives.11 Cleveland sent a letter to the Senate and the House of Representatives with evidence, such as the Blount Report and witness accounts describing the actions that took place during the overthrow. President Cleveland knew that since this was his second and last term in office, he had very little time to overturn the illegal occupation of Hawaiʻi. Cleveland on the same day also sent a letter to Liliʻuokalani, telling her it was up to Congress to decide.12

In 1894, after deliberating among themselves, the Senate submitted its report, which ended up pardoning everyone involved in the overthrow, except Liliʻuokalani. In May, a constitutional convention was held, allowing for the creation of the Republic of Hawaiʻi. In this meeting, Sanford B. Dole was appointed president of the Republic. On July 4, 1894, the Republic of Hawaiʻi was established, officially putting an end to the monarchy’s rule and to the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi itself.13 During Doles’s time as president, his main goal was to secure annexation. After several rebellions, he was able to accomplish his goal.14

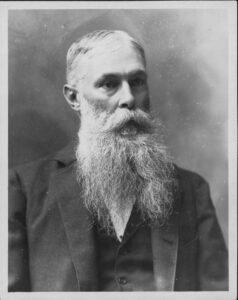

In 1895, during Doleʻs presidency, an act of defiance took place in which many Hawaiian loyalists staged a rebellion against the Republic of Hawaiʻi in an attempt to restore the monarchy’s power. This was led by Robert William Wilcox, who had previously led small rebellions from 1888-1892.15

Wilcox was a politician and lawyer, who was very pro-Hawaiian and wanted the best for his country. He fought for the interest of the Hawaiʻi people, even going against King Kālakaua when he was forced to sign the Bayonet Constitution in 1887, loosening his control of the kingdom as a whole. Wilcox saw that these actions didn’t benefit Hawaiʻi, believing at that time that Liliʻuokalani was the better leader. Wilcox started his rebellion on January 7, 1895, where he, along with 100 Native Hawaiians marched through the streets to ʻIolani Palace. However, President Dole declared martial law, forcing the loyalists to surrender. This led to the arrest of 192 Native Hawaiians, in which two members of the royal family who were in the immediate line of succession to the crown were arrested, Prince Jonah Kūhio and Prince David Kawānakoa.16 During this rebellion, Liliʻuokalani was also arrested because of her suspected involvement in starting the rebellion. She was put on trial and found guilty despite a lack of evidence, and was sentenced to five years of hard labor and a fine.17

Sanford B. Dole ended up changing Lili’uokalani’s sentence to house arrest for nearly two years before finally pardoning her.18 While in prison, she wasn’t allowed to know what was happening outside the palace. But she secretively received letters and newspapers wrapped around flowers, disguising them to get them past her guards. She wrote many influential songs while imprisoned, such as “Aloha Oe”, “He Mele Lāhui Hawaiʻi” and “The Queenʻs Prayer.” Liliʻuokalani was forced to sign abdication papers while imprisoned, and stayed eight months in an apartment on the second floor of ʻIolani Palace before being moved to Washington Place until she was granted restricted movement throughout Oʻahu on February 6, 1896. Eight months following that, she was officially pardoned by the Republicʻs executive council.19

Upon her release in October of 1896, Liliʻuokalani quickly did whatever she could in an attempt to regain her crown. She ended up mortgaging her property, and with the money she raised, she used it to travel to the U.S. in January 1897 to gain support and to slow down the annexation of Hawaiʻi. While there, she explained the events that led up to the overthrow and the overthrow itself, along with a petition against the annexation. Over half of Hawaiʻis native population had signed the petition, called the Kūʻē petitions. Through this effort made by Liliʻuokalani, she stopped the ratification of the annexation treaty of 1897. While this was a tremendous task accomplished by the Hawaiians, their victory was short-lived. With the presidential term of Grover Cleveland ending, the new president, William McKinley, had taken office, with McKinley wanting to annex Hawaiʻi. On February 15, 1898, following the sinking of the USS Maine, the war between Spain and the United States was inevitable, causing Hawai’i and its coaling station to be vital in the war. The Senate approved the bill on July 4, with President McKinley signing it into law on July 7.20 Due to the fear of the Spanish and American War, Hawaiʻi was officially annexed to the United States by the Newlands Resolution. Liliʻuokalani returned in August 1898, much to the joy of both native and foreign Hawaiians, all whom showed their support upon her arrival.21 On August 12, 1898, Sanford B. Dole gave the sovereignty and public property of the Hawaiian Flags to United States Minister Harold M. Sewall.22

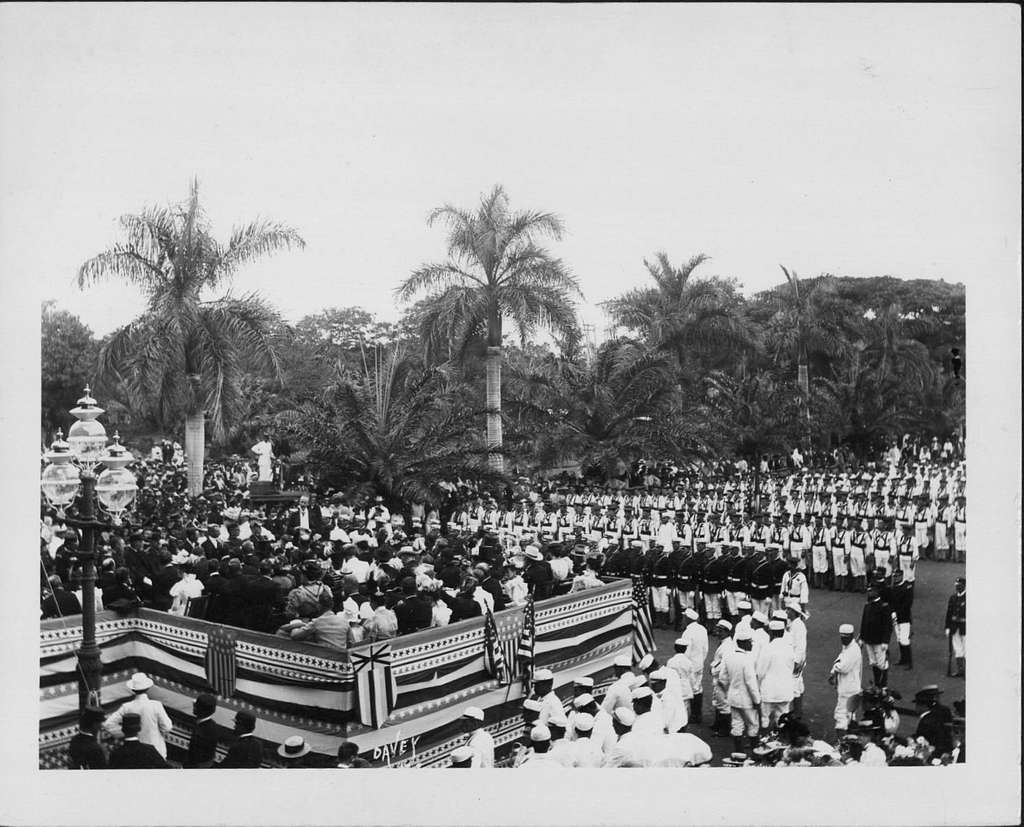

An annexation ceremony was held outside of ʻIolani Palace, where native Hawaiians in western suits and dresses offered up Christian prayers, read speeches in English, and stood alongside American troops. The former Royal Hawaiian Band played “Hawaiʻi Ponoʻi” and “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the United States Flag was raised above the palace and the Hawaiian Flag was taken down. Many Hawaiian players were seen crying, some even leaving the ceremony after abandoning their instruments.23 At Washington Place, Queen Liliʻuokalani and her extended family stayed, boycotting the event. Many Hawaiians followed in her footsteps, not wanting to see the Hawaiʻi they knew and loved being taken over by the United States. As this was seen as a celebration by the United States, Hawaiians thought of this as a mourning period for their kingdom and for what they had lost.24

After the annexation of Hawaiʻi, Liliʻuokalani ended up writing an autobiography before dying on November 11, 1917, in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. Despite being the last reigning monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Liliʻuokalani played an important role overall in Hawaiʻiʻs history. She was considered the first head Queen in the modern era of Hawaiʻi, and knew how important women’s roles were. She organized institutions for the improvement of health, welfare, and education, specifically for native Hawaiians. She was very well-spoken and an amazing composer, with many of her songs still being sung today. She learned how to be a ruler, caring about her country and her people. Unfortunately, due to the rise of immigrants and American views being pushed in Hawaiʻi, Liliʻuokalani had very little control over the destiny of the Hawaiian Kingdom. However, she still held on as long as she could, protecting both her country and her people in order for them to have a better life. She is considered an influential figure in Hawaiian history, and someone that many people continue to look up to.25

- Rachel Hatzipanagos, “Hawaiʻi’s Path to Statehood Started with an Overthrow,” Washingtonpost.Com, September 12, 2023, Gale In Context: College. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz, “Queen’s Ransom,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 66. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz, “Queen’s Ransom,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 67–68. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz, “Queen’s Ransom: How Hawaiʻi’s Indebted Last Queen Lost Her Throne to Sugar Barons and the American Rush to Empire,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 68. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz, “Queen’s Ransom: How Hawaiʻi’s Indebted Last Queen Lost Her Throne to Sugar Barons and the American Rush to Empire,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 68. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz, “Queen’s Ransom: How Hawaiʻi’s Indebted Last Queen Lost Her Throne to Sugar Barons and the American Rush to Empire,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 68. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz, “Queen’s Ransom: How Hawaiʻi’s Indebted Last Queen Lost Her Throne to Sugar Barons and the American Rush to Empire,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 68. ↵

- Elinor Langer, “Famous are the Flowers,” Nation 286, no. 16 (April 28, 2008): 17. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz, “Queen’s Ransom: How Hawaiʻi’s Indebted Last Queen Lost Her Throne to Sugar Barons and the American Rush to Empire,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 68. ↵

- George W. Baker, “Benjamin Harrison and Hawaiian Annexation: A Reinterpretation,” Pacific Historical Review 33, no. 3 (1964): 296, https://doi.org/10.2307/3636837. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz, “Queen’s Ransom: How Hawaiʻi’s Indebted Last Queen Lost Her Throne to Sugar Barons and the American Rush to Empire,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 68-69. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz, “Queen’s Ransom: How Hawaiʻi’s Indebted Last Queen Lost Her Throne to Sugar Barons and the American Rush to Empire,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 68-69. ↵

- “Sanford Ballard Dole,” Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition, March 1, 2021, 1–1. ↵

- “Sanford Ballard Dole.,” Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition, March 1, 2021, 1–1. ↵

- RALPH THOMAS KAM, “The First Attempt to Overthrow Liliʻuokalani,” Hawaiian Journal of History 55 (January 1, 2021): 41, https://doi.org/10.1353/hjh.2021.0001. ↵

- RALPH THOMAS KAM, “The First Attempt to Overthrow Liliʻuokalani,” Hawaiian Journal of History 55 (January 1, 2021): 64, https://doi.org/10.1353/hjh.2021.0001. ↵

- Eleanor B. Amico, “Liliʻuokalani,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, April 30, 2023), Research Starters. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz,“Queen’s Ransom: How Hawaiʻi’s Indebted Last Queen Lost Her Throne to Sugar Barons and the American Rush to Empire,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 69. ↵

- Lydia Kualapai, “The Queen Writes Back: Liliʻʻuokalani’s Hawaiʻi’s Story by Hawaiʻi’s Queen,” Studies in American Indian Literatures 17, no. 2 (2005): 42. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz, “Queen’s Ransom: How Hawaiʻi’s Indebted Last Queen Lost Her Throne to Sugar Barons and the American Rush to Empire,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 69. ↵

- Eleanor B. Amico, “Liliʻuokalani.,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, April 30, 2023), Research Starters. ↵

- James L. Haley, Captive Paradise: A History of Hawaiʻi (Macmillan, 2014). ↵

- Paul X. Rutz, “Queen’s Ransom: How Hawaiʻi’s Indebted Last Queen Lost Her Throne to Sugar Barons and the American Rush to Empire,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 69. ↵

- Paul X. Rutz,“Queen’s Ransom: How Hawaiʻi’s Indebted Last Queen Lost Her Throne to Sugar Barons and the American Rush to Empire,” Military History 34, no. 4 (November 1, 2017): 69. ↵

- Eleanor B. Amico, “Liliʻuokalani,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, April 30, 2023), Research Starters. ↵

2 comments

Mariana Chamorro

Liam, your publication about Queen Liliʻuokalani and the history of Hawaii is fascinating! I love how you bring to life the dramatic events and complex characters of that time with such clarity and detail. It’s clear that you put a lot of effort into researching and presenting this important story in an engaging way. Keep up the awesome work!

Cassandra Cardenas-Torres

I really liked your article it provides a. comprehensive and engaging account of the pivotal historical events leading to the annexation of Hawaii, focusing on the remarkable story of queen Liliuokalani. You skillfully unravels the the complex interplay of political, cultural, and diplomatic forces that shaped the destiny of the Hawaiian Kingdom, giving us readers a deep insight into the unwavering determination of the Hawaiian people in the face of foreign influence.