The year was 1914. Mexican rebels, with the help of the United States, were just able to successfully overthrow the corrupt political regime of Victoriano Huerta, bringing an end to the Mexican revolution. The era of bloodshed and battles and destruction that had plagued the country had finally come to an end, and Mexico could finally lay to rest an important chapter in its history and work to move forward. However, this victory did not bring peace to the country. Instead, even more blood would plunge the country into a new wave of violence. The end of the revolution left the country’s political climate in utter chaos, as various groups had differing interests in the future of the nation. These factions brought civil war and destruction across the entire country, adding to the already existing carnage left by the revolution. With Mexico’s political future up for grabs, two prominent revolutionary leaders fought for control in a rivalry that would end in a catastrophic attack on the United States.

One of these leaders was Pancho Villa, a notorious bandit turned folk hero, thanks to his military skills and daring battle strategies that led to multiple major victories during the revolution.1 The other prominent leader was Venustiano Carranza, a well-educated individual with a renowned career in politics. He served in Coahuila’s political scene and was even elected governor during the Madero presidency. Carranza became an unexpected leader in the second phase of the revolution. He was the most powerful elected official in Mexico to condemn Victoriano Huerta and declare war on his government. When Pancho Villa heard Carranza’s call for action, he became deeply interested in joining Carranza’s revolution. However, there was a slight problem; Pancho Villa had been exiled from Mexico after being imprisoned under the Madero Presidency.

Carranza’s revolution had legitimacy thanks to his political power, but it lacked military expertise, which is why his advisors sought the help of Pancho Villa. They gave him $1,000 to plan his return to Chihuahua. Once there, he would be tasked with creating a new revolutionary army for Carranza. Villa now had his opportunity to join the revolution and from that point on, Carranza and Villa proved to be crucial to the Mexican revolution. Becoming allies, however, was not as strong as it initially appeared. From the beginning of their alliance, Villa distrusted Carranza and his abilities to be the proper leader of the revolution. Pancho Villa would even refuse to recognize Carranza’s authority over the territories he captured under his leadership. Carranza shared a similar sentiment towards Villa. He saw Villa as incapable of being a true political leader for Mexico, and as a potential threat to his presidential goals. Villa, on the other hand, had an exceptionally large and loyal following, thanks to his charismatic nature.2 Once the Revolution ended, Villa and Carranza turned into rivals, and President Woodrow Wilson added even more tension between the two as he had to decide on whose government the United States would choose to recognize. Villa had support from the United States in the preliminary stages of the revolution, but due to several battlefield losses, President Wilson ended up recognizing Carranza’s government. When Villa first heard the news regarding President Wilson’s decision, his reaction was bland. He was much more interested in figuring out a way to bypass a weapons embargo that President Wilson placed, which made it nearly impossible for him to gather much-needed weapons from the United States. He figured that the best way to get over this hurdle would be to invade the border city of Sonora. He believed that this invasion would eventually allow him to control the whole state of Chihuahua, in turn diminishing the weapons embargo effects. This plan, however, completely backfired on Villa. Carranza, with the help of the U.S., was able to deploy reinforcements to the army in Sonora. These reinforcements nearly wiped out Villa’s army, this was an enormous loss for Villa. It angered him and caused his entire outlook on the U.S. to change.3

Villa felt that the United States had betrayed him. He would eventually conclude that Carranza’s recognition would spell out disaster for Mexico’s newfound independence by making it submissive to the United States. Out of anger, fear, and frustration, Villa set out to violently provoke the United States in hopes it would cause the country to enter a war with Carranza.4 Villa began to assemble his men and tried to also gather reinforcements by writing to his close friend and ally Emiliano Zapata. In his letter, Villa stated his hope that Zapata and his cavalry would join him in the north to punish the U.S. and finally be able to bring improvement to Mexico. Zapata, however, did not accompany Villa on his crusade. He viewed the idea of sending his men through vast enemy territory as highly risky. He also wished to not take his men out of their home state of Morelos. Villa disregarded this and continued to move forward with his plan. He and his men brought chaos everywhere they traveled.5 On January 10, 1916, just outside of Santa Ysabel, a horrible catastrophe took place. A group of Villa’s men, led by one of his most trusted lieutenants, Pablo Lopez, hijacked a train filled with American passengers. They stole all their possessions, including the food they carried, and after pillaging, they forced them outside the train, made them strip, and executed almost all of them. One man, Thomas Holmes, was able to escape; in total, eighteen Americans were executed. This tragic event failed to get Villa the desired outcome he wanted. The Americans were not provoked enough to come down to Mexico, so he began recruiting in small villages to continue the plan. Villa gathered more troops, increasing his army to about 250 men. With his new manpower, he began to attack small and impoverished Texan towns. After several attacks, Villa continued to recruit more men, and by the end of February 1916, he had about 500 soldiers. Villa then set his eyes on a new target. He no longer attacked small towns. Instead, he set out for a large border town in New Mexico called Columbus.6

On March 9, 1916, exceedingly early in the morning, Villa decided to attack the town of Columbus. This would mark the first major attack on U.S. soil since the War of 1812. Villa gathered his troops and discreetly rode to the outskirts of the town while its citizens were sound asleep. He ordered his men to split up into two groups of 250 to enter the town. Once his men successfully entered, they made their presence known by screaming “Viva Villa, Viva Mexico, and Muerte a los gringos,” as recalled by several witnesses of the horrific attack.7 Luckily for the townspeople, Columbus was home to Camp Furlong and had military members on hand the night of the attack. Lieutenant John P. Lucas, the commander of the machine gun group, was able to act quickly and gather his men. They began to fire at Villa’s men using their machine guns, successfully gunning some of them down. But Villa’s men were relentless and they were spread all over the town creating chaos. They burned down a hotel where they executed several townspeople, ransacked homes, and looted several stores. After a couple of hours of nonstop lighting, Villa’s men with all the loot they stole began to race to the border after the town’s soldiers began to successfully push them back. Villas witnessed this attack from the outskirts of the town where he stayed with his reserve. Major Frank Tompkins saw Villa’s men retreating and with the permission of Colonel Slocum, he was able to gather some men and chase after Villa and his troops. In his pursuit, while blindsided by the event that had just occurred, Tompkins crossed the U.S. border into Mexico without permission from either side. Once he realized this, he sent one of his men back to Columbus to gather instructions from the Colonel on how to continue. The man came back with instructions for Tompkins to pursue, using his own judgment. So, with these instructions, he pursued, hoping for justice, but Villa would not go down so easily. He was able to set up three counterattacks that would wound Thompkins and several of his company’s horses. These counterattacks caused Thompkins to come to the realization that he and his men were too deep into Mexico and did not have the necessary number of resources to pursue Villa any further, prompting him to head back into the United States.8

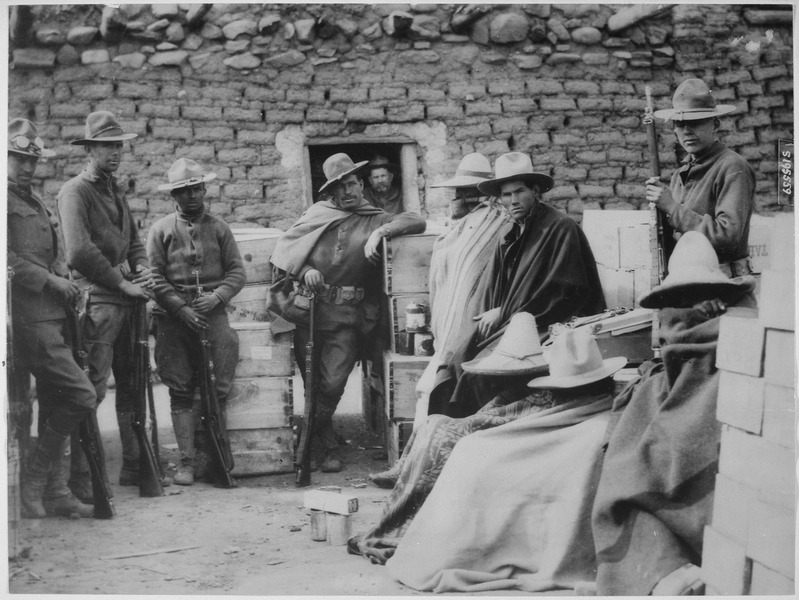

The raid was a bloodbath for both parties involved. Villa lost approximately 67 of his men, while the town of Columbus lost 18 of its residents, and 10 of those casualties were regular citizens. This raid, coupled with the previous attacks on U.S. soil, led President Wilson to become engulfed with rage toward Villa. Too much American blood had been shed, so to put a stop to the madness, President Wilson ordered a punitive expedition in which he would send 5,000 U.S. soldiers into Mexico to follow Villa and either capture him or kill him for his crimes.9 During this time, the U.S. military was small, only consisting of 108,399 soldiers. So sending 5,000 troops was a big deal. On March 15, 1916, just six days after the Columbus attack, the expedition led by General John J. Pershing crossed into Mexico. Tensions between Mexico and the United States were high, and it did not help that Carranza was against the idea of U.S. troops being stationed in Mexico. Carranza’s refusal made it difficult for the expedition to properly function. The search for Villa was proving to be challenging, as it seemed impossible to gather proper intelligence regarding Villa’s location, as locals refused to help due to their strong anti-American sentiment and the fact that nobody really knew his true location. Villa kept it very well hidden. At times, most of his own officers would not even know his true location.

On March 27, 1916, Villa was shot in the leg after delivering a speech about the U.S. invasion that Carranza had allowed to come into Mexico. His men quickly took Villa into hiding. The punitive expedition was unknowingly hot on Villa’s trail. They had just entered the town of Guerrero, and Villa was just outside of this town on the move. The expedition ran into several of Villas’s men in this town, causing a fight to break out. It ended with thirty of Villa’s men dead, but this was the closest the expedition had come to ever catching Villa. After some time, Carranza’s men began to fully refuse to help the United States. Pershing interpreted this action as them working with Villa and his men, leading to several conflicts between the two groups. After ten months of the expedition, President Wilson decided to end the expedition and bring his men back home after several failures to capture Villa. The expedition was not a total loss, as Villa was left in a weakened state and would unlikely ever attack the U.S. again.10 In the early 1920s, Villa once again regained some of his power, thanks to his relentless nature. He now had a plan to attack Carranza once again and take over Ciudad Juarez. Ultimately this, like many decisions in his life, backfired on Villa. He was not able to take over the city, marking the end of his guerilla leadership ways. He was able to secure a presidential pardon from Carranza and decided to retire and live the rest of his life in a hacienda near Chihuahua. This plan was cut short as he was executed shortly after.11

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2023 , s.v. “Pancho Villa,” by Judith R. Johnson. ↵

- Alejandro Quintana, Pancho Villa a Bibliography (Santa Barbara: Greenwood, 2012), 39-69. ↵

- Friedrich Katz, “Pancho Villa and the Attack on Columbus, New Mexico,” The American Historical Review 83, no. 1 (1978): 101-115. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2023 , s.v. “U.S Invasion of Mexico,” by John Powell. ↵

- James W. Hurst, Pancho Villa and Black Jack Pershing: The Punitive Expedition in Mexico (Westport: Connecticut, Praeger Publishers, 2008), 5-11. ↵

- Jeff Guinn, War on the Border : Villa, Pershing, the Texas Rangers, and an American Invasion (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021), 25. ↵

- Thomas Boghardt, “Chasing Ghosts in Mexico: The Columbus Raid of 1916 and the Politicization of U.S. Intelligence during World War I,” Army History, no. 89 (2013): 7. ↵

- Gary Glynn, “Attack on Columbus,” Army History 35, no. 5 (2000): 60-62. ↵

- ABA Journal, 2020 , s.v. “March 9, 1916: Pancho Villa’s Battle of Columbus,” by Allen Pusey. ↵

- Julie I. Prieto, Mexican Expedition, 1916-1917 (Executive Agency Publications, 2016), 33-67. ↵

- Friedrich Katz, The Life and Times of Pancho Villa (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), 400. ↵

9 comments

Fernando Milian

It is sad to see that after all the fighting, Villa’s efforts to lead did not end well for him. His life seemed to be full of battles, not just against others but also for his own leadership and beliefs. His story is definitely a dramatic example of how power struggles and politics can lead to serious conflicts and personal downfalls.

Sebastian Hernandez-Soihit

Great work! very well written account of Pancho Villa’s work and especially important in this fiesta season in which we are invited to have fun, but also think about what is means to live in Southwest United States and the historical implications that the current borders have.

Leaya Valdez

Hello Leonardo! Great work with the storytelling of the history of Pancho villa, i have never fully heard about Villa but seeing how courageous he was about going against the U.S. and how the U.S was trying to fight against him and his army.very interesting to learn about the boarder and just how the people in the villages were so supportive of his movement and idea. Great job!

Walter Goodwin

I really like the article, I think Pancho Villa’s mindset and his ambition to gain power is particularly interesting. His initial alliance with Carranza despite his distrust of him, to me shows how he wanted to use him to gain power for himself. Villa’s feeling betrayed at the United States and hoping to goad them into attacking Carranza shows how vindictive, vengeful and brutal he was towards people he felt were his enemies.

Vianna Villarreal

Such a great way to inform on Mexican history. Pancho Villa played a major rule in challenging U.S. rule which was impactful to the Mexican mindset till this day. There are so many Americans who neglect the fact that Texas and numerous parts of the United States was originally part of Mexico which we took. It is unfortunate to see that countless of people like Pancho Villa are villains in American history which in reality they are the heroes of their people and their ancestors.

Quinten Mero

Great job! Pancho Villa’s tale is one of excitement and great intrigue and you have certainly done it justice with your article. It was interesting to learn about Pancho Villa’s influence in the region and the legacy he left behind. I didn’t know that the U.S. went after Pancho Villa past the U.S.-Mexican border both with the following of Pancho Villa’s raiding party from Columbus and en masse with General Pershing’s punitive expedition. I found that very interesting.

Jonathan Flores

This article was very well written, and the storytelling aspect of the article remained interesting an engaging the whole time. In addition, I really appreciate how I was able to learn more about the famous figure of Pancho Villa. As a Mexican American, it was nice to hear more about a figure in our culture that is often referenced. All in all, the article was done well and was greatly informative on an interesting topic.

Ana Barrientos

Hi Leonardo! First I liked the way you told Pancho Villa story, and the images that you used. It flowed well with the story. Pancho Villa is definitely a very famous figure in Mexican history, I remember learning a little bit about him when I was little because at one point he was the governor of Chihuahua and I often heard his name because I was born in Chihuahua. Even though I knew his name I never knew the whole story and I love how informative your article was.

lramirez46

A very well-written article about the infamous Pancho Villa. I like the way you described how he had started to escalate tensions with the U.S. due to his emotion of betrayal since President Woodrow didn’t recognize Villa’s government. You do a good job of describing the way Villa would attack border cities and how locals would refuse to help the United States and could not properly locate Villa.