1938—A modern artist by the name of Piet Mondrian has left Paris to escape a paranoia that he had been developing, despite France being a safe zone for artists at the time. As a modern artist, Mondrian felt that he was threatened by the Nazis for the type of art he was making, and that maybe Paris, being so close to Nazi Germany, was too unsafe for him, at least in his mind. The reason for his developing paranoia about the Nazis emerged when the Nazi regime held their “Degenerate Art Exhibit” in 1937.

In this Exhibit, the Nazis showcased 740 art pieces by modern artists for the sole purpose of ridiculing and mocking their art. The modern art under attack included art from the styles of impressionism, cubism, expressionism, Dada, and Bauhaus.1 Not only were Mondrian’s pieces showcased as exhibits of “degenerate art,” but so were many other prominent artist’s pieces displayed, such as the work of Vincent Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Wassily Kandinsky, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Otto Dix, and Paul Klee.2 The art that they created was denounced by the Nazis as “barbarism of representation,” “decadent of culture,” “nature as seen by sick minds,” and “madness becomes method.” From the Nazi point of view, modern art was nothing more than the promotion of degeneracy and idiocy, something that they claimed was absolutely disgusting and offensive, and must be avoided and destroyed. Many modern artists were much affected by these pronouncements, so much so that it took a physical and mental toll on many of them. Some artists in Germany were put in concentration camps, and some artists even committed suicide because they couldn’t handle the harsh treatment they had to endure. That was the fate of the famous expressionist painter of Die Bruecke group in Germany, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. After hearing these stories about how horribly modern artists were being treated in Germany, and what the Nazis were saying about modern art and doing to modern artists, Mondrian became worried, even paranoid, about the Nazis, just from the fact that they were aware of who he was and where he was. From this, Mondrian developed a mentality that he was “endangered” and had to “flee” from Paris, despite the fact that Paris was free from Nazi rule in 1938. And so Piet Mondrian left for London, or “fled from Paris” as his paranoia led him to see it.3

But above all, Mondrian also yearned for a nurturing and supporting art community that understood his art and appreciated it for its merits. Born and raised in Amsterdam, Mondrian had exposure to the arts at an early age. By the time he was twenty-two, Mondrian was accepted to Amsterdam’s Academy for Fine Arts, which helped him to establish a reputation as an acclaimed landscape painter. In 1912, Mondrian arrived in Paris, where he had been able to freely develop his art style by experimenting with the styles of impressionism and cubism. Then in 1914, WWI broke out, which led him to resettle in an artists’ colony in the Netherlands, where he would continue to experiment with these art styles. In 1917, while living in Laren, Mondrian met an artist named Theo van Doesburg, and together, they founded the De Stijil (The Way) art style.4

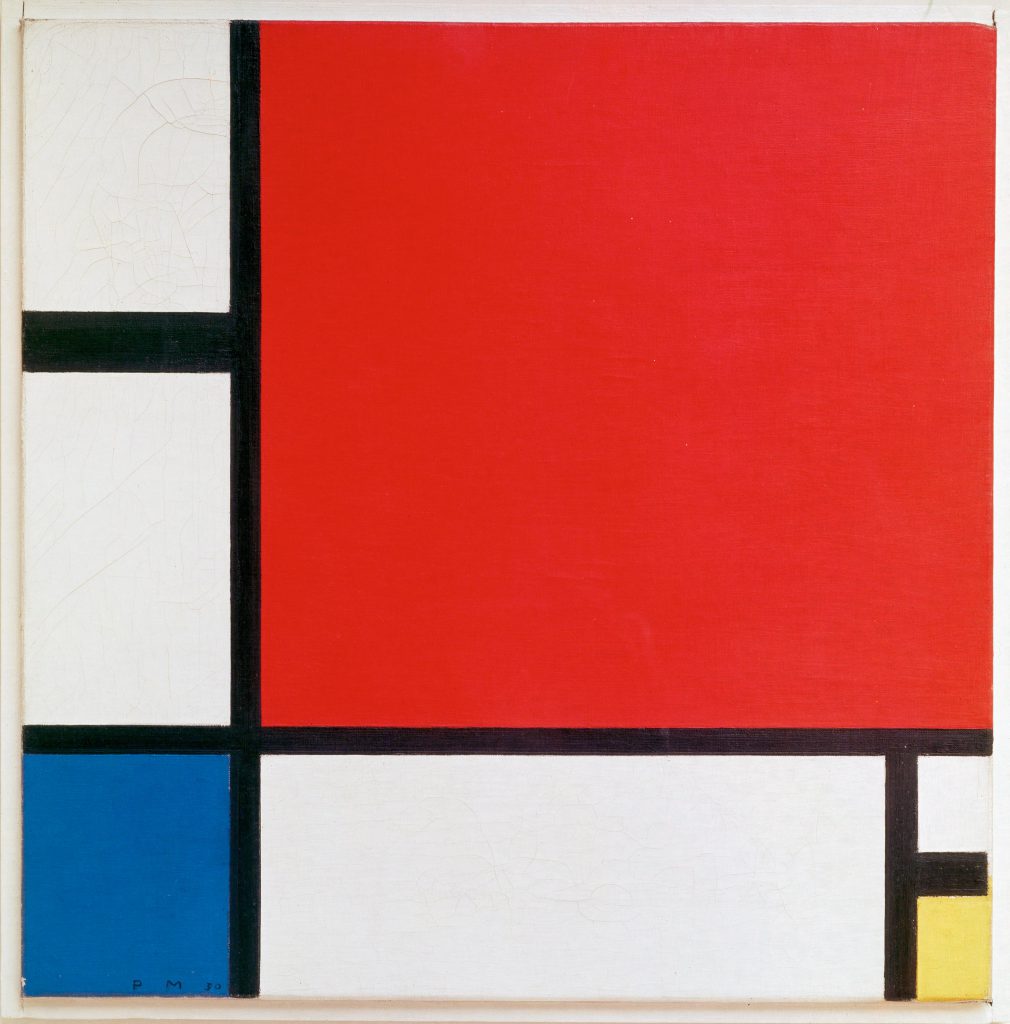

Mondrian coined the term Neo-Plasticism to help define De Stijil as geometrical abstract paintings limited to primary colors as well as the colors black, grey, and white. In 1919, Mondrian returned to Paris from Laren to develop his De Stijil art style, where he promoted his artistic ideas to the art community of Paris. Mondrian remained in Paris from 1919 to 1938, when he left for London. During his stay in Paris, Mondrian was finding great success and recognition in his art career. He was even able to be successful without a nurturing art community that might actively engage with him. Mondrian essentially had nothing but his own artistic ideas to build upon on his own. However, once the Nazis came to power, the amount of progress Mondrian had been making with De Stijil was put in jeopardy. Despite living in a Paris that had not yet been conquered by Nazi Germany, Mondrian still felt the hand of Nazism. His work as an artist had been targeted and labeled as something degenerate and lacking of any artistic skill or merit. Mondrian’s lack of an art community had immediately become a disadvantage, as he felt that no one would support him and his career. This made Mondrian realize that the only way he could get back on his feet, so that he could create the type of art he wanted, not the type of art Hitler and the Nazis wanted, would be to find a community of supportive and nurturing artists.5

In 1938, Mondrian came to London to escape Nazi attitudes towards modern art. Initially in early 1938, Mondrian didn’t want to leave Paris. However, when Mondrian became aware that his pieces were showcased in the Degenerate Art Exhibit, he realized that not only would his art career decline, but more importantly, his life would be in great danger. This predicament was the exact same situation many other modern artists were in: flee Europe, or stay in Europe and fear for their lives. In truth, Mondrian made the decision to leave Paris for New York, where his work was already held in high regard. However, a British friend of Mondrian had persuaded him to go to London instead, so he could join up with other European artists that were similarly “on the run” from the advancing Nazi regime. Mondrian was indeed welcomed by this group of artists in London, called The Circle. But unfortunately, this was not the type of art community that Mondrian was searching for and hoping to join. Yes, these artists were supportive of him, but they offered him nothing of inspiration, nor suggestions that would help him improve and develop his art. It is as if they just let him do his art on his own with no artistic communication between Mondrian and the group, which helped contribute to Mondrian’s lack of artistic development. Mondrian did in fact enjoy himself while he was in London, mainly because he enjoyed its jazz clubs and cinema. Despite his personal enjoyment, when considering his artistic endeavors, London was distracting, unfruitful, and generally extremely unproductive. Mondrian made zero developments to his art style, and he only completed a few of his Paris pieces. He didn’t start any new pieces.

Then in September 1940, Mondrian’s stay in London came to a close when the London Blitz began, that is, the Nazi bombing of London during the Battle of Britain. As horrible as it may sound, the London Blitz may have actually been beneficial to him, as it broke him away from these distractions and made him realize that he needed a safer place to work on his art with an art community that would back him up. Later in the month, Mondrian arrived in New York after a two-year delay.6

Upon arriving in New York in late 1940, he was immediately welcomed by the art community, including the heavily influential art collector and critic, Peggy Guggenheim.7 It should also be noted that even while in Europe, Mondrian had received considerable praise from the New York art world, being compared to and regarded as highly as other Dutch artists, including Rembrandt and Van Gogh. So it’s no wonder that he was welcomed by New York’s art community after building quite the reputation. More importantly, now that Mondrian had found his supportive community, he immediately began new art projects, while also experimenting and improving upon his art style, something he had not done in years. Some even say that the amount of experimentation Mondrian did in New York was the same amount he had done during the early days of his career. During his stay in New York, his art form began to change. He adopted the influence of the liveliness of New York City and even the city’s layout. Mondrian had also discarded his use of black lines and chose to use primary colored lines to form a rhythmic blend of horizontal and vertical lines. These new developments can be reflected in his piece, “Broadway Boogie Woogie.” Mondrian also interacted with the people in New York’s art world, much to his benefit, and he even participated in numerous art shows and exhibits, this time not the ridiculing and insulting kind, but rather the kind that celebrated and uplifted his art. Additionally, Mondrian also found various opportunities to sell his art works. Not only did Mondrian work on canvas , but he also worked on designing his entire art studio in the style of De Stijil. Upon walking through Mondrian’s art studio, prominent artist Willem de Kooning said that the studio was “like walking around in one of Mondrian’s paintings.”8 Essentially, what New York did for him was give him a breath of new life for his art career and give him new success and inspiration, thanks in part to the fact that he found and was accepted by a nurturing and supporting art community.9

Despite four years of newfound success, Mondrian unfortunately died of pneumonia in 1944. Closely after his death, photographer Fernand Fonssagrives described a sensation he had felt while inside Mondrian’s studio. The sensation was an overwhelming feeling of Mondrian’s vision and ideas that radiated from the studio itself. It was almost as if Mondrian’s presence or spirit had been present in the studio itself. This statement solidifies the fact that New York’s art community contributed to a resurgence of inspiration and creativity in his art career.10

Even after death, Mondrian is immortalized by the people that utilize and appreciate his art style and has become an artist held to a high esteem. His work is regularly showcased at some of the world’s most famous museums, including but not limited to the Museum of Modern Art, The MET, and the Guggenheim Museum. Furthermore, his acclaim is solidified by the fact that after his death, his work has sold for tens of millions of dollars, with “Victory Boogie Woogie” selling for $40 million.11 Additionally, many aspects of Mondrian’s De Stijil is present in many aspects of modern-day designing practices, which include the design of logos. Interestingly, Mondrian’s writings on De Stijil has translated to principles correlating with asymmetry and horizontal/vertical rhythm in modern architecture, chiefly in terms of design.12

- Authors and Artists for Young Adults, 2006, s.v “Degenerate Art Exhibit” by John Merriman and Jay Winter. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2019, s.v. “Nazi Germany Hosts the Degenerate Art Exhibition,” by Robert Brown. ↵

- Authors and Artists for Young Adults, 2006, s.v “Degenerate Art Exhibit” by John Merriman and Jay Winter. ↵

- Authors and Artists for Young Adults, 2005, s.v. “Piet Mondrian” by Authors and Artists for Young Adults. ↵

- Piet Mondrian, Piet Mondrian : the studios : Amsterdam, Laren, Paris, London, New York (London and New York: Thames and Hudson, 2015), 232-234. ↵

- Piet Mondrian, Piet Mondrian : the studios : Amsterdam, Laren, Paris, London, New York (London and New York: Thames and Hudson, 2015), 232-234. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, 2019, s.v. “Piet Mondrian,” by Hans Jaffe. ↵

- Piet Mondrian, Piet Mondrian : the studios : Amsterdam, Laren, Paris, London, New York (London and New York: Thames and Hudson, 2015), 232-234. ↵

- Yve-Alain Bois, and Amy Reiter-McIntosh, “Piet Mondrian, ‘New York City,'” Critical Inquiry 14, no., 2 (1988): 244-247. ↵

- Piet Mondrian, Piet Mondrian : the studios : Amsterdam, Laren, Paris, London, New York (London and New York: Thames and Hudson, 2015), 232-234. ↵

- Nancy J. Troy, The Afterlife of Piet Mondrian (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 9-10. ↵

- Yve-Alain Bois. “Mondrian and the Theory of Architecture,” Assemblage, no., 4 (1987): 104. ↵

34 comments

Sara Guerrero

I remember in art class in middle school doing a painting that looked like Mondrians and I never learned why we were panting how we were until I read this article. I have read of the Nazi’s taking paintins for their greediness, but I never knew theyr would mock othe artist like Pablo Picasso. I understand why Mondrian would feel persecuted and why he had to move and it’s great to see the opportunities he got in America.

Estefanie Santiago Roman

Initially I was very surprised to read about the Nazis holding a show to make fun of artists, this is something that I hadn’t heard before. It is quite interesting to see that the Nazis would make fun of modern art, seen as it is one of the most popular and fast growing style of art in past couple of years. As to Piet Mondrian, I do recognize some of his pieces and I remember seeing one of his pieces on display when I visited the national art gallery in Washington D.C.

David Castaneda Picon

I have seen some of the art work of Piet Mondrian before, and I have always liked his style. Although I have heard about this artist before, I have never read about the story of his life and the challenges he faced and I think this article did a great job telling the story of Piet Mondrian. It must have been very difficult for Piet to leave his country because of his art. I don’t think it was a surprise that many people did not accept his artwork at that time because it was clearly something new for the spectators.

Berenice Alvarado

This article is really informative. I love the way that the writer provides background to understand Mondrian’s life. I don’t know much about Piet Mondrian but when I read this article I felt sad. Sad that he had to leave the place where he started his work. In a way it was a good thing because when he got to the U.S. he found the purpose he was seeking for. But sad that the reason he left was because he was scared to express his feeling through art. And the main reason because the thought of modern art didn’t fascinate the Nazi and he was scared to be killed. I found this article interesting.

Janet Dizinno

Thank you for a beautifully written and informative piece on one of my favorite artists. (Admittedly, I have many “favorites.”) It is heartbreaking to think that such lovely works could lead to destruction and ridicule. I look forward to reading more work by you.

Sebastian Azcui

I really did not have idea about Piet Mondrian’s works of art and that he was a famous artist. Piet lived a crazy life and during a period of many tragic events. All of these experiences helped him live this life and helped him in his art career as he could draw these events and visualize them. One of his greatest arts is Paris during the Nazi regime. One hard moment that Piet had to pass through is to leave his country and become an exile. Imagine being exiled just for painting.

Courtney Pena

I remember seeing some of the artwork on this article in my art class in high school. I remember recreating our own version of it but I was never taught about the history behind it. This article does a great job at doing so. It is unfortunate that he got kicked out of his own country for doing art. At least today, his art is loved and known by many people today.

Briana Montes

Overall, very we’ll written article. I enjoyed learning about Piet Mondrian and his history. I liked how one of the arts was Paris during the Nazis rule in Germany.It was really heartbreaking to read how much damage the Nazis did to everyone. I have always been a big fan of art and I find these articles very interesting. I didn’t know anything about Piet Mondrian before reading this article but I feel like I learned a lot.

Dr. Pierucci

What a great story and artist to highlight! Thoroughly enjoyed the Grey Tree artwork and the inspiration evident within the Rietveld Schröder House.

Cassandra Sanchez

It is really heartbreaking to see how much damage the Nazis did to everyone in this time period and how much paranoia was created and how it changed everyone’s lives. I was only briefly aware of how the art community was affected so I found it interesting to see how it was from a single man’s perspective. Piet Mondrian created great artwork and it was really interesting to see how in his journey to safety he experienced setbacks in Paris where his career didn’t move forward or backwards but eventually him being pushed out and to New York helped him for the better.