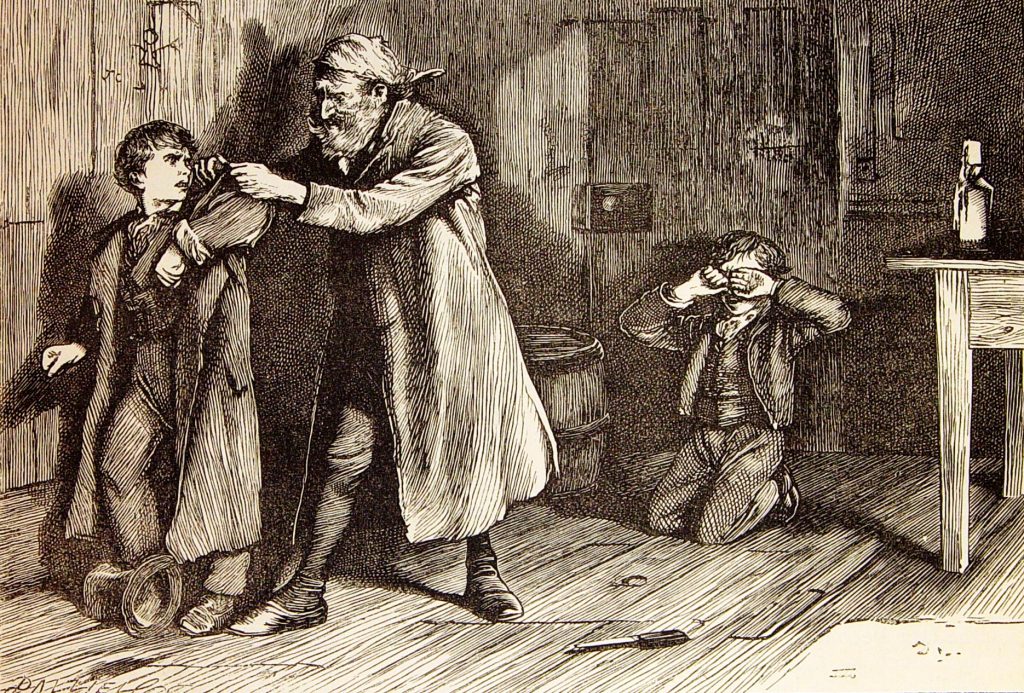

Long days filled with long hours filled with over-exhaustion, minimal pay, and no food. These were the standard conditions in industrialized work factories. These commonplace injustices were memorialized in the classic book Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens. The haunting line remembered generations after it was written, “please sir, I want some more” 1. The heart wrenching story of an orphan indebted to miserable workhouse conditions captured the public’s attention. With a wry cherubic protagonist, the industrialized world had no choice but to turn its eyes and hearts to the inhumanity permeating its industries.

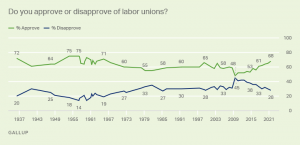

Oliver Twist bridged the gap between the latent public and labor union sympathies. Similarly, 250 articles on the topic of labor unions were published in the New York Times alone, between the years of 1934 to 1957. That is nearly eleven articles a year from one newspaper. According to the Pew Research Center labor unions maintained an average approval rating of 71.5 between the years of 1937 and 1955 2.

This is important because Diane E. Schmidt in her systematic content analysis “Public Opinion and Media Coverage of Labor Unions” found that mass media coverage “influences public opinion by controlling what people know about an activity.” She directly ties her finding to the public’s approval of labor unions and the media’s coverage of the topic 3.

This theoretical relationship matters tangibly when discussing policy. Without the sympathetic media coverage in the late 1800’s to mid 1900’s the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (NLRA) would not have passed. The NLRA changed the face of unionization by legally giving workers the right to bargain collectively about wages, hours, and conditions 4. The fight for labor union rights exemplifies the impact the media has on influencing legislation. Without the massive amounts of coverage and support labor unions received, the NLRA would not have been implemented.

For those who are disenfranchised, the media is perhaps the single most effective tool. By using mass communication to implicitly or explicitly endorse or stranglehold causes, media becomes the weapon that shapes our culture. Because of media support, movements like labor union rights, women’s suffrage, and protection of women in the workplace have grown into policy changes.

The discussion of women’s rights has always wafted through our culture and policies. Legislators have made laws regulating women and their bodies, discriminating against women in social, public, and private spheres, and continuing to maintain the idea that there are integral differences in men and women’s performance, personalities, and abilities. Women have been ignored in the legislative process in two contrasting ways: 1) a denial of existence/citizenship and thus laws are not meant to be applied to them or 2) disenfranchisement and denial of autonomy based on lesser intellectual capacity. Many remember Anita Hill, one of the first women to openly testify about sex and gender harassment in the workplace. But many do not vividly remember the arduous, pre-existing fight for gender equality in the workplace as well as we remember this single televised event.

The first codification equalizing men and women could have been in 1868 when the 14th and 15th Amendments were added to the Constitution. But with the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendment to the Constitution, explicit exclusion of gender was also added. In Minor V. Happersett (1875), Virginia Minor argued under the Privileges or Immunities clause, which states “the citizens of each State shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States,” that women were entitled to suffrage. However, the Supreme Court ruled in a unanimous opinion penned by Chief Justice Morrison Waite that the term “citizen” was synonymous to “inhabitant” and men and women were inherently different types of citizens, thus Minor was not being restricted of her rights because she was already an enfranchised woman 5. In this decision Waite distinguished that a man and woman were entitled to different liberties based on their gender.

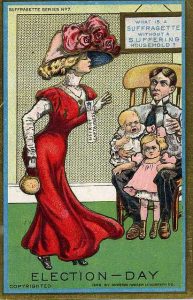

Similarly, the rhetoric surrounding the women’s suffrage movement focused on what women were intended to provide to society as women, not people. The anti-suffrage movement argued that women wouldn’t have time to stay updated on politics or even vote because they would be too busy with their children and the household. These ideas pervaded newspapers, presenting themselves in articles and cartoons.

The National Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage (NAOWS) was a heavy developer of these messages. Susan E. Marshall analyzes NAOWS’ media impact on the suffrage movement in her ideological content analysis “In Defense of Separate Spheres: Class and Status Politics in the Antisuffrage Movement.” Marshall pulls from The Women’s Protest NAOWS’ monthly publication which had a national audience. Marshall states “rhetoric reflects movement ideology and, by articulating individual orientations to social issues” it explains and shapes cultural understanding. Marshall finds that 57% of publications opposed to women’s suffrage relied on the theme that the mobilization of women would lead to the detriment of American society. Through identifying the concerns propagated in media, Marshall highlights the fear of individual female liberty being raised above the working family unit. Women’s suffrage was seen as an attack on American society and gender roles. The messaging of NAOWS cultivated the fears that still drive the derisiveness between men and women’s rights 6. This negative portrayal of the suffragette movement created a stain that was hard-pressed to be removed. The American public reacted by fighting against the 19th amendment until 1920. In fact, the messaging of NAOWS was so powerful that adversaries of the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s echoed the same arguments.

One of the next monumental addendums to the Constitution was the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (CRA). This act “prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin” according to the official legal definition. The CRA was fueled by the increasing cultural awareness through media of the Civil Rights Movement. Through mass communication the Civil Rights Movement gathered both sympathizers and adversaries. Their message was shared nationally on tv, radio, and newspapers and because of this, a legislative policy called the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. Added last minute were the protections on sex-based discrimination. It is debated whether this was a sincere attempt at protecting women in the workforce or if it was an attempt to tank the CRA 7. With an unknown motive it is difficult to look at the CRA’s sex-based protections as sincere. Still, despite the legal protection of women against discrimination there was a lack of enforcement, unification, and supervision to ensure that women were treated equally. In response President Lyndon B. Johnson strengthened the CRA with executive orders directed at government contractors. He ordered equal opportunity of employment and established the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs. This noble attempt at lessening discrimination in the government workforce was ill-fated as cultural dissonance heightened and more and more the public became polarized on the topic of race and sex discrimination during the late 60’s. The policy supported the idea of equality in the workforce, but on the small scale, day to day, women struggled to be hired much less treated or paid the same.

By 1990 the feminist movement had been working through the ranks of politics for over a hundred and fifty years and still the discrimination of women continued. Thus, the Civil Rights Act of 1990 was conceived. The CRA of 1990 specifically discussed the unlawful discrimination in the workforce on the basis of sex. This bill can be used to target sex and gender harassment in private, state, and federal sectors. This bill would allow women the ability to sue against a larger power when mistreated on the basis of sex. This power was blocked previously by the burden of proof and narrow scenarios recognized within legislation as being illegal 8.

This anti-discriminatory policy passed through the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate before being egregiously vetoed by then-president George H.W. Bush. And in taking a moment to evaluate this situation, Bush was able to veto this bill without major backlash because workplace sex and gender harassment policy was not an interest generator for the media. Bush quietly pushed the CRA of 1990 out the door because he could. There wasn’t a single story to unite America, there was no face to attach to the movement. Without mass media involvement the push for sex-based anti-discriminatory policy came to a standstill.

Anita Hill became that face. The galvanizing figure of Anita Hill set fire to the discussion of workplace sex and gender harassment. She publicly testified in 1991 during the Senate confirmation hearing of Clarence Thomas as a U.S. Supreme Court nominee. Clarence Thomas had previously been her supervisor in the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Committee (EEOC). As Professor Anita Hill calmly described the horrifying and uncomfortable situations, we watched her story unfold on live television in the familiar way women know. Workplace sex and gender harassment didn’t just appear, but all of a sudden it was visible. Visible in the way truth is. Visible in the way you can reach out and touch it. Anita Hill, on our television, was visible. Women had been suffering silently, alone because that was expected and socially acceptable. Our society perpetuated systemic sex and gender harassment in the workplace and until Professor Hill’s testimony, many women did not know what they were experiencing was illegal. The normalization of workplace sex and gender harassment had simply been a part of working for many women, and especially those who did not know it was actionable 9.

Anita Hill was a paragon of what it means to be alone, sitting in front of an all-white, all-male committee. And yet, Anita Hill testified because she knew she wasn’t the only woman to experience sex and gender harassment. In a New York Times interview Professor Anita Hill gave in 2019 she said that she believes “to measure progress, [is] not just about in my lifetime, but to measure progress through the lifetime of women, to realize that we have moved forward, but also to take the long view in looking forward to thinking about what we can do for the next generation” 10. Anita Hill is so much more than her testimony. But her testimony gave so much to us, to women who needed a voice.

According to Gallup, 86% of Americans watched “at least some part” of the hearings and 77% of Americans followed the news coverage of the committee hearings 11. Hill’s testimony reached hundreds of thousands of Americans. The live and recorded news coverage as well as interviews brought sex and gender harassment into public light. It became a public conversation through the media.

The next month the Civil Rights Act of 1991 was passed. Similar to the CRA of 1990 it was an addendum to the previous CRA of 1964. This act expanded a woman’s rights to sue and collect compensation and punitive damages for sex and gender discrimination or harassment. This Act sought to rectify situations that are often wrought with power dynamics and unequal footing. It also included what is called the “reasonable woman” standard, a guideline of determining what constitutes sexual harassment from the view of a reasonable woman 12.

The CRA of 1991 was a direct result of Anita Hill’s groundbreaking testimony. Because in front of the entire nation, Anita Hill united the public’s attention.

A good summary of the problems with the legislation to protect women in the workforce, “the bill has a good heart, but the solution that it proposes is inadequate to repair these salient problems” 13. Without a strong, adequate solution women cannot hope to live and work equally. Anita Hill’s testimony was the provocation that captured the media’s attention, but we did not do enough with the momentum. And without mass media attention surrounding an adjacent topic, we may never have comprehensive codified protection for women.

The public pays attention to what the media depicts. Our radios, TVs, newspapers, and social media tools are all gateways to information. All separate avenues that lead to different places. Policy change happens when the entire airport of media has the same layover. When there is a national focus on an issue there is a greater probability of legislative change. The media’s portrayal of a topic is integral in the public’s understanding of situations, and it necessarily informs the way we react. Without a sympathetic media, a cause is doomed to struggle tumultuously until a brilliant lens captures the iconic face we associate with a movement. As with the discussion of Industrial Labor Unions, the Women’s Suffrage movement, and Anita Hill, the way society responds to the demands of marginalized communities is biased and informed by our exposure through media. And without the media we would all be left asking, “please sir, I want some more” 14 while waiting for change.

- Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist (Bentley’s Miscellany Book), 1838 ↵

- Gallup, Labor Unions (Pew Research), 2021 ↵

- Diane E. Schmidt, Public Opinion and Media Coverage of Labor Unions (Labor of Journal Research), 1993 ↵

- William Domhoff, The Rise and Fall of Labor Unions in the U.S. (Who Rules America), 2012 ↵

- Steven A. Shull, American Civil Rights Policy from Truman to Clinton: The Role of Presidential Leadership (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharp Inc.), 1999 ↵

- Susan E. Marshall, In Defense of Separate Spheres: Class and Status Politics in the Antisuffrage Movement (University of Texas at Austin), 2001 ↵

- Juliet R. Aiken, Elizabeth D. Salmon, and Paul J. Hanges, The Origins and Legacy of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Journal of Business and Psychology), 2013 ↵

- 101st Congress, S.2104 Civil Rights Act of 1990 (Labor and Human Resources), 1989-1990 ↵

- Kimberle W. Crenshaw, We Still Have Not Learned from Anita Hill’s Testimony (University of California), 2019 ↵

- Anita Hill, How History Changed Anita Hill (New York Times), 2019 ↵

- Megan Brenan, Gallup Vault: Anita Hill’s Charges Against Clarence Thomas (Gallup), 2018 ↵

- K L Kirn, Reasonable Woman Standard in Sexual Harassment Cases (Illinois Bar Journal), 1993 ↵

- William R. Corbett, Intolerable Asymmetry and Uncertainty: Congress Should Right the Wrongs of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 (Oklahoma Law Review), 2021 ↵

- Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist (Bentley’s Miscellany Book), 1838 ↵

5 comments

Cassidy Colotla

I love the way this was written! It gives so much information. As a feminist I think it’s so important to learn about issues highlighted here such in this article. It’s really sad how labor used to be for people, but I’m glad we have come a long way and are continuing to improve. You did a great job of writing this in a strong yet sensitive matter. Good luck with your nomination!

Paula Ferradas Hiraoka

Hello Sophia,

First of all, congratulations on your nomination and getting your article published!

Very insightful! This article was pretty well-written and it’s a highlight of the sex and gender harassment plus the several inequalities respecting woman in the workforce. It’s also so impressive how influential and vital media can be in the regulations.

Overall, amazing work and good luck!

Anissa Navarro

This article was so well written and truly highlighted the sex and gender harassment as well as inequality with woman in the workforce. It also mentioned the multiple sources of media society has and how we can use those to help instigate change instead of just being bystadners.

Elisa Fronapfel

Well written and a valuable assessment of the work done to create an equitable platform for women in our society.

Amanda Swan

Very insightful! So fascinating to see how influential and vital media can be in industrial policy regulations. Great work!