At a quiet New York cemetery in 1959, a handful of people stand around a fresh grave as a casket is lowered. Any passerby seeing the small somber ceremony might assume that the body belonged to a person of little significance. In fact, this casket carries the body of a man who is responsible for one of the largest shifts in international law in human history. Without his efforts, it is likely that the gravest crime mankind has ever committed and continues to commit would still be a crime without a name.

By the end of World War II, the Nazi regime had orchestrated the murder of over 17 million civilians in concentration camps throughout Europe. 1 Despite these egregious atrocities, no one at the time referred to the Holocaust as an act of genocide, not because it was not an appropriate descriptor, but because Raphael Lemkin had not yet coined the word and defined the crime for the world. The outcome of his personal crusade to encode ‘Genocide’ in an internationally recognized and binding Convention to which the US would sign on became his legacy (the US signed on decades after his passing).

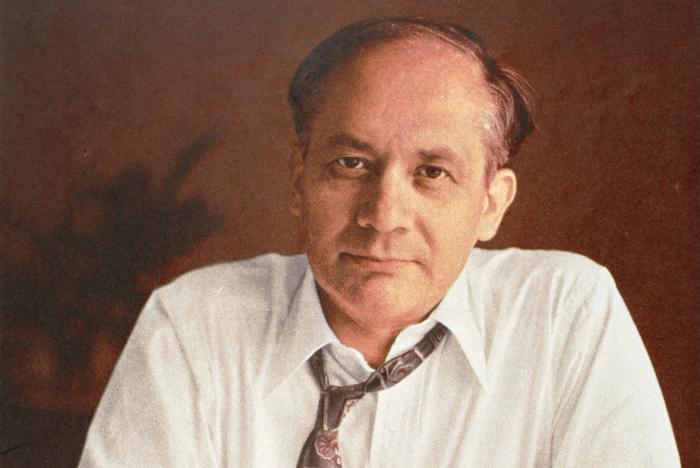

Lemkin was born to a Polish-Jewish family in 1900 in a small village called Bezwodne in what was then The Russian Empire. Home schooled by his mother, he proved to be a brilliant scholar. By the time he received his undergraduate degree from Jan Kazimierz University he had learned over 14 languages and showed strong aptitude and interest in international law. After a career as a prosecutor in Poland, he was forced to flee to Sweden to evade capture by the Nazi forces in 1939. However 49 of his relatives were tortured and/or killed, drops in the ocean of inhumanity that was the Holocaust. 2

After fleeing the Nazi invasion, Lemkin eventually made his way to the United States. There he became a prolific professor, lecturing at the law school at Duke University in 1941 and the School of Military Government at the University of Virginia in 1942. He also served as an adviser to the United States War Department specializing in international law. 3

The world first became aware of Lemkin’s concept of genocide after the publication of what would arguably be his most important work, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, in 1944. Primarily a legal analysis of the behavior of Nazi Germany in occupied territories during World War 2, the book also contained a full definition of the crime Lemkin dubbed “genocide.” 4 After this publication, Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to getting the international community to acknowledge genocide as a crime under international law.

Lemkin drafted a resolution for a treaty which would officially ban genocide under international law. He then took his resolution on the road, presenting it to any nation which would hear him, hoping to garner enough support to endorse a convention on the subject. After years of lobbying the international community, The United States UN delegation agreed to present Lemkin’s resolution to the General Assembly. Dubbed “The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” the resolution was adopted on December 9th, 1948. It would be another 3 years before enough countries signed on the the convention to make it enforceable. Much to Lemkin’s dismay, The United States was not one of the first 20 signatories. 5

Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to lobbying those nations which had not yet signed onto the convention, with the United States being his primary target. He invested every moment of his time and every cent of his modest wealth to landing that particular white whale. He eventually died of a heart attack, impoverished, unemployed, and underappreciated, in 1959. His funeral was a small affair, reportedly only attended by 7 people. 6 Yet, today, the is no Law School, no class that teaches Human Rights, nor any conversation of World War II and any of the subsequent Genocides that does not mention his name. More importantly, the Convention provided some tools to prevent or punish such cases.

The greater legacy of his life’s work would not be realized until several decades after Lemkin’s death. The United States would eventually sign the Genocide Convention, but not until 1988. The international community would eventually convict a man of the crime Lemkin coined, but not until the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 1998 which found Jean-Paul Akayesu guilty of the Rwandan genocide. Three years after that, Radislav Krstic was similarly convicted for the murder of 8,000 Bosnian Muslims in Yugoslavia. 7 Though he died nearly 40 years too early to see the fruits of his labor truly flourish, we can hope that his soul finds solace in the fact that, thanks to him, these heinous actions have a name and are viewed the world over as being among the worst crimes humanity has ever known. Eradicating the crime of genocide still eludes us but at least accountability is now more widespread around the world. 8

- Donald Niewyk and Francis R. Nicosia, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University, 2000), 43. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- Rafael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress, (Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Department of International Law, 1944) pg. 79. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Jay Winter, “Prophet Without Honors” The Chronicle, June 3, 2013, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Raphael-Lemkin-a-Prophet/139515 . ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- United Nations, “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” United Nations Treaty Collection, 78:1, 1021 (9 December 1948), New York: United Nations, 1951, 278-311. ↵

196 comments

ramaya2

This article is well researched and very engaging. The article examines Raphael Lemkin’s role in defining genocide as an international crime as well as outlining potential repercussions to African security. It dives into the legal, human, political, and historical impacts of genocide prevention that further emphasize Africa’s experience with widespread atrocities. Lemkin’s work helped create the foundation for international legal mechanisms like the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) that helped influence legal responses to conflicts in Darfur, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and South Sudan. It also discusses the political challenges of imposing genocide conventions, selective international intervention, and the struggle for historical recognition of African genocides. The only critique I may provide is that it could strengthen its focus on African security by expanding on regional case studies to build greater historical context.

Carollann Serafin

This article was really well researched and insightful and I enjoyed hearing the work of Dr. Lemkin learning about the Genocide convention that took place and we did not learn about it up until 40 years alter after it’s occurrence. This history changes international relations and although we did not get to see his work put all in we can tell that the large amount of research he did made a difference in the world. I am glad I got to learn more about this topic by reading this article and by far has been my favorite.

Lashanna Hill

Finding out that an individual who was able to avoid being captured by Nazis by fleeing to Sweden and ended up being the one capable of getting the holocaust recognized as a form of genocide, was very interesting. Especially with the ongoing conflict between Palestine and Isreal that started around the same time in 1948 and The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was drawn by the General Assembly (GA). Crazy how history just keeps repeating itself.

setter

Hi Matthew – thank you so much for detailing the work of Raphael Lemkin in your article. I became familiar with his work in the book A Problem From Hell by Samantha Power, which details the 20th century problem of genocide and dedicates significant time to the work and contributions of Lemkin. As you noted, he is featured heavily in our academic studies of genocide and international law. But he isn’t known colloquially and most people outside of that field wouldn’t know his name, even though they would know the word “genocide.”

mortiz39

This article highlights the immense impact of Raphael Lemkin’s work on international law and genocide prevention. It’s compelling to learn how his advocacy laid the foundation for accountability in cases like Rwanda and Bosnia. Including a discussion of how genocide shapes African security and the global response would enhance the article’s depth.

ejuarez8

I believe a more thorough examination of Lemkin’s struggles to get the Genocide Convention adopted will enhance the piece. Even though his lobbying is well-documented, the reader may better understand why his efforts took so long to succeed if they included more information about the political climate of the day, such as opposition from powerful nations. Lemkin’s work would also be more relevant to current international relations if a brief explanation of how his legacy informs current genocide prevention initiatives was included.

adelao4

Wow! What an amazing article. As someone deeply interested in International Law, I believe Mr. Lemkin is a pivotal figure in this field. He was a visionary researcher who helped the world recognize the horrors his people endured and the potential for similar atrocities to occur in the future. His work led to the identification of what he called ‘a crime without a name.’ It’s unfortunate that he didn’t live to see the full impact of his life’s work, but I’m confident that he found justice in the recognition of past, present, and future genocides.

enorwood

It’s interesting to learn that Lemkin and the term he coined were not fully appreciated in his lifetime. Although I wasn’t aware of his extension battle to get the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crimes of Genocide, I was aware of the foundation in his name – The Lemkin Institute for Genocide Prevention and Human Security. It’s also surprising to learn that the US was so hesitant to sign on when it pushed for the Nuremberg trials. It’s good to see that Lemkin’s legacy and impact was eventually recognized.

Nicholas Quintero

I think this article has done an excellent job at not just just establishing the fact that Raphael Lemkin was a very accomplished and intelligent man, but that his effort on genocide was his life’s work. Establishing that Lemkin continued his effort on having genocide be recognized even after the UN had enough signatures to adopt the resolution, such as his effort with the United States. Lemkin passing away impoverished and underappreciated but was never deterred from his efforts was portrayed and told wonderfully in this article, especially with the ending about his efforts finally paid off, years later.

cravagnani1

Hello Matthew. I loved how you provided a detailed overview of Lemkin’s life and his work. I believe this allows us to understand better the significance of his work. It is unfortunate that he did not get to see the whole picture of his work, but like you mentioned he changed the history of international relations. His persistence and dedication to his work are inspiring as if he found his purpose on this earth. I enjoyed reading your work and getting to know more about the origin of the world Genocide, which for some of us who are not in law school goes unnoticed.