At a quiet New York cemetery in 1959, a handful of people stand around a fresh grave as a casket is lowered. Any passerby seeing the small somber ceremony might assume that the body belonged to a person of little significance. In fact, this casket carries the body of a man who is responsible for one of the largest shifts in international law in human history. Without his efforts, it is likely that the gravest crime mankind has ever committed and continues to commit would still be a crime without a name.

By the end of World War II, the Nazi regime had orchestrated the murder of over 17 million civilians in concentration camps throughout Europe. 1 Despite these egregious atrocities, no one at the time referred to the Holocaust as an act of genocide, not because it was not an appropriate descriptor, but because Raphael Lemkin had not yet coined the word and defined the crime for the world. The outcome of his personal crusade to encode ‘Genocide’ in an internationally recognized and binding Convention to which the US would sign on became his legacy (the US signed on decades after his passing).

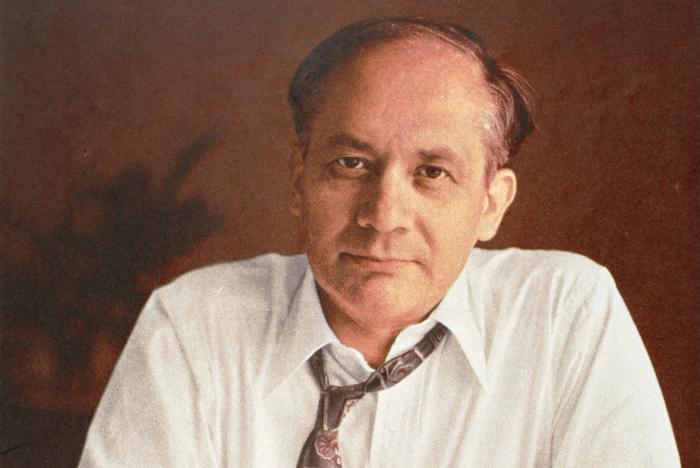

Lemkin was born to a Polish-Jewish family in 1900 in a small village called Bezwodne in what was then The Russian Empire. Home schooled by his mother, he proved to be a brilliant scholar. By the time he received his undergraduate degree from Jan Kazimierz University he had learned over 14 languages and showed strong aptitude and interest in international law. After a career as a prosecutor in Poland, he was forced to flee to Sweden to evade capture by the Nazi forces in 1939. However 49 of his relatives were tortured and/or killed, drops in the ocean of inhumanity that was the Holocaust. 2

After fleeing the Nazi invasion, Lemkin eventually made his way to the United States. There he became a prolific professor, lecturing at the law school at Duke University in 1941 and the School of Military Government at the University of Virginia in 1942. He also served as an adviser to the United States War Department specializing in international law. 3

The world first became aware of Lemkin’s concept of genocide after the publication of what would arguably be his most important work, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, in 1944. Primarily a legal analysis of the behavior of Nazi Germany in occupied territories during World War 2, the book also contained a full definition of the crime Lemkin dubbed “genocide.” 4 After this publication, Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to getting the international community to acknowledge genocide as a crime under international law.

Lemkin drafted a resolution for a treaty which would officially ban genocide under international law. He then took his resolution on the road, presenting it to any nation which would hear him, hoping to garner enough support to endorse a convention on the subject. After years of lobbying the international community, The United States UN delegation agreed to present Lemkin’s resolution to the General Assembly. Dubbed “The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” the resolution was adopted on December 9th, 1948. It would be another 3 years before enough countries signed on the the convention to make it enforceable. Much to Lemkin’s dismay, The United States was not one of the first 20 signatories. 5

Lemkin dedicated the rest of his life to lobbying those nations which had not yet signed onto the convention, with the United States being his primary target. He invested every moment of his time and every cent of his modest wealth to landing that particular white whale. He eventually died of a heart attack, impoverished, unemployed, and underappreciated, in 1959. His funeral was a small affair, reportedly only attended by 7 people. 6 Yet, today, the is no Law School, no class that teaches Human Rights, nor any conversation of World War II and any of the subsequent Genocides that does not mention his name. More importantly, the Convention provided some tools to prevent or punish such cases.

The greater legacy of his life’s work would not be realized until several decades after Lemkin’s death. The United States would eventually sign the Genocide Convention, but not until 1988. The international community would eventually convict a man of the crime Lemkin coined, but not until the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 1998 which found Jean-Paul Akayesu guilty of the Rwandan genocide. Three years after that, Radislav Krstic was similarly convicted for the murder of 8,000 Bosnian Muslims in Yugoslavia. 7 Though he died nearly 40 years too early to see the fruits of his labor truly flourish, we can hope that his soul finds solace in the fact that, thanks to him, these heinous actions have a name and are viewed the world over as being among the worst crimes humanity has ever known. Eradicating the crime of genocide still eludes us but at least accountability is now more widespread around the world. 8

- Donald Niewyk and Francis R. Nicosia, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University, 2000), 43. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- Rafael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress, (Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Department of International Law, 1944) pg. 79. ↵

- Raphael Lemkin and Donna-Lee Frieze, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). ↵

- Jay Winter, “Prophet Without Honors” The Chronicle, June 3, 2013, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Raphael-Lemkin-a-Prophet/139515 . ↵

- Robert Bliwise, “The Man Who Criminalized Genocide,” Duke Magazine, November 14, 2013, http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/article/man-who-criminalized-genocide . ↵

- United Nations, “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” United Nations Treaty Collection, 78:1, 1021 (9 December 1948), New York: United Nations, 1951, 278-311. ↵

196 comments

Carlos Alonzo

I was thoroughly impressed and appreciate the information presented and the story-telling method used to convey the concepts and ideas attributed to Raphael Lemkin’s legacy. It’s remarkable how the word “genocide” was coined by Lemkin and overall, it’s tragic how the events led to the creation of the word. Prior to the article, I was not aware that the word was coined by someone specific.

Jonathan Flores

This article is very good but very unique in its own respect. That is to say, genocide is one of the most deplorable aspects of mankind and human history ever, yet the article takes a cautious approach to the defining of that very topic. In other words, the article takes an unprecedented stance on the issue of genocide by provided a more robust and analytical description of the person who coined its term, and provides great information on the topic. This is particularly useful to me as in many cases the issue of genocide is extremely difficult to read about, yet this article presents its subject matter in a much more digestible way. As a result, I must comment on how the tone of article does a masterful job at encapsulating the seriousness of the topic while giving information about the topic that generally speaking, most people haven’t thought about before. Therefore, good job.

Vianna Villarreal

This infographic is perfect when trying to express the unfair and unjust acts of the United States Government in their history. Numerous Native Americans, Colored Americans, Latino American, etc. have faced injustice. Being obligated to serve a country that does not fully want to accept you or allow you to be considered an American. Lemkin did the exact thing any latino with power would have done.

Mikayla Trejo

Thank you for sharing the origins of the word “genocide” and Lemkin’s story. This information is interesting, and its crucial to keep history in our discourse as scholars. Especially traumatic history such as this. Overall, this passage was informational and relevant.

Alexis Silva

This article does an amazing job at emphasizing Raphael Lemkin’s significance by highlighting how he coined the term “genocide,” and his impact on the Crime of genocide. Lemkin contributed to international law and the understanding of crimes against humanity. Prior to reading this article I had no knowledge of him, but now I have caught an interest and will be doing more research. I appreciate how this article introduced an important individual who positively impacted society.

Linda Aguilar

I truly enjoyed reading about how Raphael Lemkin education started at home with his mother and finished with a background in International Law. His United Nations ID, gravestone and photo of Lemkin at The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 1948 were excellent visual aids in his story. The timeline and flow of the article was detailed and informative.

ldena

This such a well made reading, while I obviously have heard many things about the tragedies of World War II I feel as if there is always so much more left to learn and Lemkin’s story is definitely one of those things. While his story is bittersweet, I believe that everyone should still be so proud of what this man did. He fought so long for something so big yet not many people could see it. Im glad that now it is something that has made a big change to international law and I hope his work continues to live on. Other than that this was a great story on a great person, it was very engaging and powerful, a great read.

dolivaresvasqu

Great Piece on Lemkin someone who is undoubtedly an important piece of history for the political science community. An important concept given a name that shaped the international perception of the idea of eliminating certain ethnic groups, thanks to his work we can now identify this as an act against humanity and very immoral. Now that this issue is internationally recognized it will give other nations permission to intervene in global affairs that affect the populous of another nation for the better as well as possibly prevent further genocides and punish perpetrators.

aramon11

Matthew, confronting such a tough subject with the grace that you did was great. Your opening paragraph describing the small funeral was a great hook into the rest of your story. Though Mr. Lemkin did not live to see his work fulfilled, I’m glad it finally was utilized. His hard work to define such a crime against humanity deserves to be remembered. This story brought light to a man’s life with and connected it with a word that I thought was as old as time.

esaucedomoreno

This article provides better pictures when it came to explaining what was being talked about. I found it really interesting when I learned about Raphael Lemkin, a scholar who dedicated his life to ensure that the community realized that genocide was considered as a crime in the context of international law. This article provided with more citations which technically means that it’s more of a trustworthy piece of work.