It was a cold, quiet night, and for Robert Smalls, that could either be life changing or life ending. Smalls gathered his crew and steered the Planter away from the dock. Confederate soldiers were everywhere they turned, and they had only a small gap to succeed. No one knew what was about to happen that day, yet Smalls’ crew still believed in him.1

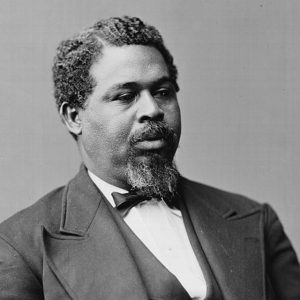

It was April 5, 1839 when Robert Smalls was born a slave in Beaufort, South Carolina.2 His young life was very protected under the arms of his mother. She never wanted him to have to face this life of cruelty. However, that didn’t mean she didn’t want him to see what it was like to be a slave. After long days in the fields, Robert’s mother would take him to see how the other slaves were being treated. They were owned by Mr. Mckee, who was a very bad man and always mistreated his slaves. Around the age of twelve, he was sent to Charleston to work and to make money for his slave master. He knew he had to work hard and follow the rules so that he would not be sold. At the end of the day, his master was a bad man, but by working for him, he had the opportunity to stay close to his mother. Smalls worked many jobs in Charleston, from lamp lighting to working at a hotel. There, at the hotel, he met Hannah Jones. And in 1856, Robert and Hannah were married, and shortly after that, they had two children.3 Now having a family began to change Smalls’ mindset. He knew how difficult it was to be a slave and how hard it was when he was a kid. This made him start thinking about saving money and getting a better paying job. Soon after, he got a job as a longshoreman, a sailmaker, and any odd job that dealt with the water and boats. He was introduced to the cotton carrying ship industry, where he learned all kinds of skills, including what it took to be a pilot for these ships. However, blacks were not allowed to be pilots. He still made the effort to become one.

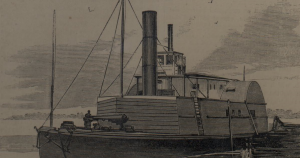

In 1861, the Civil War broke out, and while Smalls was secretly on the North side, because African Americans where free there, he had to work for the Confederate Navy. As the war grew, Robert was made a wheelman on a gunboat called the Planter. Since Robert had some time working with boats and the sea, the white commanders of the Planter began trusting him to steer the ship in and out of the harbor. During this time, Robert and his fellow slave co-workers took notes of the specific skills that the white commanders had. The war started to get worse and the price to buy his freedom and his family’s freedom skyrocketed up. He had to think of a new way to gain freedom. Charleston at the time was heavily guarded and it was risky to try and escape by land. This gave him the idea of escaping by water because the Nothern Fleet was anchored just 7 miles away.4

The idea of escaping began to grow to the point where he could not stop thinking about it and the great things it would bring to his family. He knew he couldn’t succeed by himself, yet he wasn’t alone. The Planter had another six slaves working on it as well. Robert discussed his plans with his crew and gladly they were persuaded to join him. The only request from them was that they be able to take their wives and children as well.5 The plan was on, but they also had to think about what would happen to them if they failed. They came to agreement that if they were at risk of getting caught at sea, they should blow up the ship and all aboard rather than allow themselves to be captured and sent back to being slaves with a bad punishment waiting for them. However, what if it did work? How would they be able to pull this off? Smalls knew the distance from the harbor to the Union side. He learned when the white crew would return and when they would usually go on break. Smalls was a knowledgeable man, which helped him memorize the hand signals used when steering past other Confederate ships. The rest of the crew had qualities that would also help the escape. After a while, they knew that the best time to escape was at night.6

On May 12, 1862, the Planter had just returned from a job. It was a usual thing, and Smalls knew that. The Planter was full of ammunition and weapons, ready to be delivered the next day. As the white crew finished up and completed their duties, they left the ship to attend a ball. Robert and his crew knew that it was the perfect time and the right day, and that they would not get a second shot. It was around 3 am on May 13, 1862. Robert and the crew sprang into action.7 They made sure all their wives and children were accounted for. Once that was done, they began to get the boat ready. They fired up the boiler and pulled up the Confederate flag. Months of planning and waiting began to feel worth it. Time was tight, because they had to leave before sun up. Robert put on his captain’s straw hat and started to steer the ship away from the dock towards Johnsons. Once out, they were spotted by a fellow sentry. Thankfully, Robert put good attention of his captain’s motions and signals when steering the ship, because as they got near the Union side, one last Confederate boat was passing by. As they passed by, Smalls and his crew hid the women and children and blew the horn as a normal Confederate ship would. Yet they were still scared. They passed the enemy near Fort Sumter, but in a short while the Confederate boat figured out that the Planter had been hijacked. Smalls was too far for them to get shot down or captured, and they continued their voyage to freedom. Once safe and at a good distance, they brought down the Confederate flag and swapped for a white flag that signified that they were coming in peace to surrender the Planter to the Union Navy. They reached the Union side by Cummins point, which for Smalls was a big thing. Years of wanting to be free and leave a life of slavery had become a reality.8

Smalls turned over the Planter, which was filled with weapons and ammunition. But for the Union, they gained something bigger than physical objects. They gained detailed knowledge of what the Confederates were planning. Smalls was rewarded and a new life was about to begin for him and his family. He spent the rest of the war working for the Union Armed forces and even served as pilot of the Planter during the war. He joined the free black delegates of 1864 and became a spokesperson for all African Americans.9 He advocated for African American equality, education, and even the economic opportunities they could get. Smalls knew that he wanted to be free and have a better life, so he decided to make it a reality no matter what the cost was.

- Louise Meriwether, The Freedom Ship of Robert Smalls, Young Palmetto Books (Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2018), 17. ↵

- Lisa Perry, “Robert Smalls,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, May 1, 2022). ↵

- Bruce G. Terrell, Gordon P. Watts Jr, and Timothy J. Runyan, “The Search for Planter, the Ship That Escaped Charleston and Carried Robert Smalls to Destiny,” ed. National Marine Sanctuary Program (U.S.), Maritime Heritage Program series ; No. 1, (2014):11, https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/11743. ↵

- Louise Meriwether, The Freedom Ship of Robert Smalls, Young Palmetto Books (Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2018), 15, 16. ↵

- Beverly C. Tomek, “SMALLS, ROBERT (1839-1915) American naval officer and politician,” Encyclopedia of Free Blacks and People of Color in the Americas, by Stewart R. King. Facts On File, 2012. ↵

- Edward A. Miller, “Escape of the Planter and War Service,” in Gullah Statesman, Robert Smalls from Slavery to Congress, 1839-1915 (University of South Carolina Press, 1995), 1-2. ↵

- Louise Meriwether, The Freedom Ship of Robert Smalls, Young Palmetto Books (Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2018), 22. ↵

- Edward A. Miller, “Escape of the Planter and War Service,” in Gullah Statesman, Robert Smalls from Slavery to Congress, 1839-1915 (University of South Carolina Press, 1995), 3. ↵

- Beverly C. Tomek, “SMALLS, ROBERT (1839-1915) American naval officer and politician,” Encyclopedia of Free Blacks and People of Color in the Americas, by Stewart R. King. Facts On File, 2012. ↵

4 comments

Jacob Salinas

I enjoyed reading and learning about Robert Smalls, an enslaved person during the civil war who made a daring escape. In my opinion, Robert Smalls showed tremendous bravery and courage by escaping his cruel owner. After his escape, Robert Smalls helped the Union in different ways. He gave them intel on the Confederacy and also was a pilot for the Union during the Civil War. Robert Smalls advocated for African American rights in education and economic opportunities.

Kristen Leary

What an article! I have never heard of Robert Smalls before, so it was surely an interesting read. I liked the imagery you gave at the beginning to set the scene since it was a different time and place. Slave to freedom stories are always an interesting read, and I would be interested to see what he did after reaching freedom.

Griffin Palmer

I found it very interesting to learn about Robert Smalls and his escape from slavery by sea. It shows that Robert Smalls was just seeking the opportunity of living the life of a simple man like every other slave and cared deeply for his family. However, he would be given the opportunity to escape the imprisonment of slavery for himself and his family by gathering a ship that would allow them to escape with the knowledge he had of ship handling. It was definitely one of the most slave stories I’ve heard.

Hailey Koch

Smalls was born into slavery and didn’t know any other way of life. He was a hard-working man that made sure he did his best every day at his job so he was able to stay close to his mother. When he had kids of his own he started seeing everything from a different perspective. This is the only life he knew, but he didn’t want that for his kids. He knew he had to do something and it’s crazy how he risked it all to become free. He did what he had to do no matter the outcome. No one knew if his plan would fail or succeed, but he did it anyway with a slight chance of success. Since they were successful they will be able to give their children the best lives and they won’t have to live the lives their parents did.