Many have heard the history of the Russo-Japanese War, that led to the surprising defeat of a powerhouse nation like European Russia by the small Asian nation of Japan. But, history has failed to give credit where it is due, namely to the Japanese Naval Commander-in-Chief, Tōgō Heihachirō. He led the Japanese Navy to success throughout this conflict, with his demonstration of leadership capabilities, strategy, and aggressive fighting style.

Tōgō Heihachirō was a naval officer and son of a samurai of the Kagoshima Clan. After the Meiji Restoration, he went to Great Britain to study the British Navy. After returning and showing his competence in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, he was made captain of the Naval Division. Right before the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, he became Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet.1

At a young age, Heihachirō left for London, where he received English language training and instruction in European customs and decorum. Togo proved to be a gifted student and even graduated second in his class. He continued to impress not only his peers but his instructors with his determination and will during drills. When he returned home to Japan, he was immediately met with the conflicts he had missed while living abroad. He fought during the Franco-Chinese War, Sino-Japanese War, and soon to be Russo-Japanese War. As the war was seen on the horizon, he was made Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, making him the nation’s foremost naval leader.2

This conflict had been brewing for quite some time between Russia and Japan. One of the underlying causes of this dispute was the exploitation of China. Japan had defeated China in the Sino-Japanese War and because of this, it gained possession of Formosa and the Liaotung Peninsula. European countries, however, were not quick to recognize this claim from an Asian country. France, Germany, and Russia intervened to force Japan to renounce its claims on the Liaotung Peninsula, and Russia began to stake its own claims in the same region. Russia had already begun to expand into Manchuria (northeastern China) in order to extend its Trans-Siberian Railroad. After telling Japan that their claims to the Liaotung were invalid, Russia herself went in and secured it. Through this process, they were also able to acquire Port Arthur, a major resource. The Russians were able to do this by using bribery and sheer will of the force. Russia was then able to expand its presence into Manchuria and Liaotung.3

Meanwhile, Japan grew frustrated, enlarging her armed forces, and forging a defensive alliance with Great Britain. It was clear that Japan was preparing itself for a war to avenge the insult that Russia had clearly handed to them, and to regain the dominant position that they had already won in China.

The situation became even more intense when Czar Nicolas II of Russia began to show interest in expanding into Korea. This was aimed right at the heart of Japan, which had a long history of imperialism in Korea. Once Japan learned of this, they became convinced that diplomacy alone would not be able to solve this conflict and keep Russians out of Korea.4 This led to an inevitable conflict between Japan and Russia that Admiral Heihachiro was about to initiate.

The Japanese strategy militarily was to hit fast, hard, and first, with armies landing on the Liaotung Peninsula. Their success on land was due to moving swiftly; they had already passed into Manchuria and secured their hold there before the Russians could do anything to sufficiently block them. But, this was all based on the efforts on the sea; failure of the navy would force Japan to withdraw further down the Korean peninsula, which they did not want. This would have allowed the Russians additional time to block the advance toward Manchuria. Failure to maintain sea control would threaten the communications and supply of the Japanese forces. Therefore, the responsibility for success or failure landed firmly on the shoulders of Admiral Togo and his fleet.5

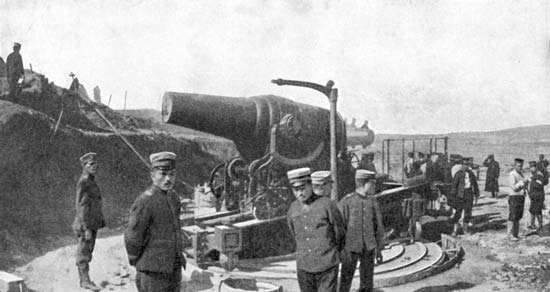

While Togo was serving as the naval cadet during his time in England, he adopted the style of Lord Horatio Nelson as his inspiration. These elements can be seen in the naval war with Russia, specifically during the preemptive torpedo attack at Port Arthur. Togo’s motto in the face of war was often led by the idea that he must ensure the destruction of his enemy in order to minimize the risk of his own forces. As an island nation, Japan needed to establish and maintain control of the sea to protect and transport troops. Togo was also under the restriction of only having to fight the war with the ships he had on hand. There was an added risk of losing the small fleet Japan possessed. The advantage was that Japan’s six battleships and six armored cruisers of Togo’s battle line were faster than Russia’s seven battleships and four armored cruisers.6 Japan also had a considerable advantage in weapon technology, and further, a superior enhanced navy, with better morale and training than Russia. The Russian navy was filled with morose faces led by officers with no real military training, experience, or leadership qualities, other than family connections.

Togo began his naval campaign by sending a cruiser to cover the landing of the army’s advance parties. News of this never reached the Russians because of the cutting of the telegraph cable, thus cutting off communication between Russian forces. This left Port Arthur’s defenses ill-prepared for Togo’s surprise attack, which damaged some of the Russian fleet. This also mentally stalled the soldiers of Russia, who had never expected an aggressive, straight-forward attack. Togo took advantage of this and established his fleet to become a ghostly presence, with continuous bombardment and patrolling of the port. When the Russian squadron attempted to flee from the port, the two forces met. Togo was able to showcase the might of the Japanese fleet, and the Russians quickly reversed back.7

Although things did not go perfectly, and Admiral Togo didn’t execute the plan as smoothly as he desired, he was able to learn and adapt. He learned from his early mistakes and corrected them. One of the earlier weaknesses that he understood and began to improve on was the low-level skills and inadequacy of the destroyer fleet.8 Togo’s strategy succeeded in keeping the Russian’s in such a demoralized state that Port Arthur was surrendered to the Japanese largely by default.9

Heihachirō was a strong, decisive leader who took risks in order to ensure success, and this strategy paid off. The Russian navy was the opposite, in that it was unwilling to take any risk whatsoever. By allowing uncontrolled Japanese deployment and supply, the strategy also aided in the success of the Japanese armies. As author T. J. Betts put it, “From the Russian point of view, delay [was] most advantageous.”10 This sped up the capture of the port and the loss of the fleet’s sanctuary. Moreover, the lack of active strategy from the Russians only added to the dissolution of the morale within the Russian crews, and, simultaneously, boosted Japanese morale.11 The Japanese Army and Navy coordinated well together, and in the end, achieved their military objectives. After trial and error, Admiral Togo learned from the early mistakes made and corrected them. He had noticed the weaknesses of the Russian fleet and adjusted his strategy appropriately.12

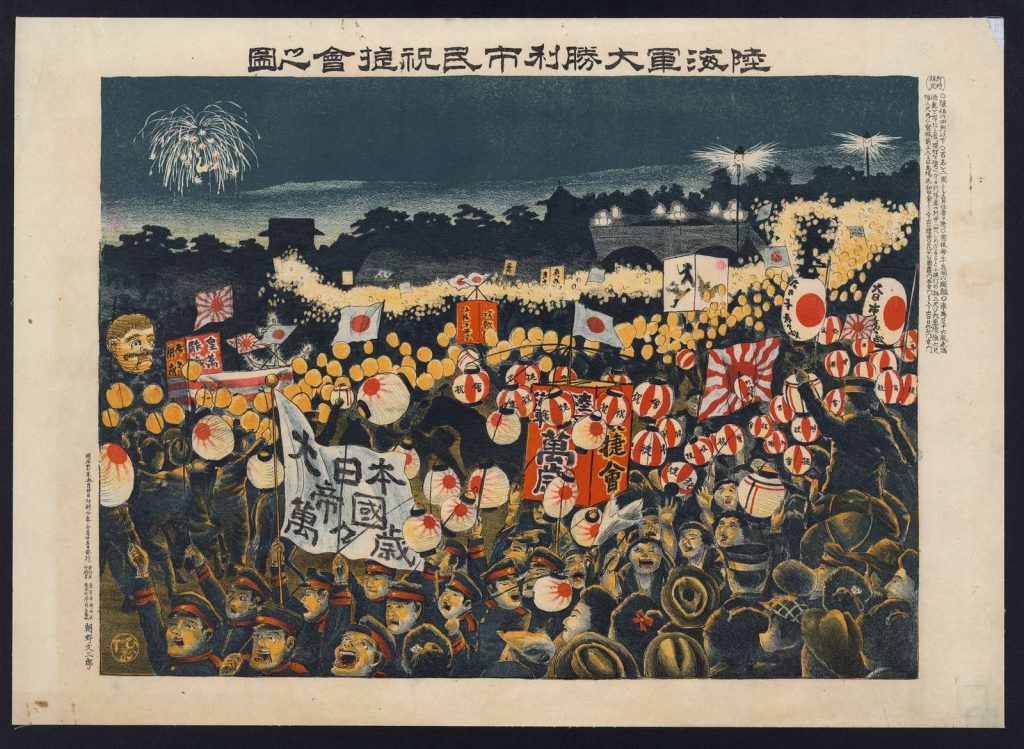

The Battle of Mukden was the last battle fought in the Russo-Japanese War, and once again was led by the great and trusted, Admiral Togo. The end result was a victory for Japan, but not without severe casualties. The Russian Baltic Fleet, which had been long delayed due to poor sea conditions, ultimately encountered Admiral Togo’s fleet at the Tsushima Straits in May 1905. The Russian naval force did not stand a chance and was destroyed without a single loss of the Japanese fleet.13

The success starting at Port Arthur, made possible by Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, set the tone for the way the rest of this war would play out. It took only a year, from the siege of Port Arthur in February 1904 to the negotiations in September 1905, for the Russo-Japanese War to end.14 This war was one of the few that have been fought between countries that were seen as modern industrial powers that were caused by the pressures of imperialism and colonial exploitation. Both sides did not want to budge when the war had finally come to an end. Russia believed that she was not truly defeated, while the Japanese saw seeking peace as a perceived weakness. Japan, realizing it could no longer sustain a war militarily, politically, or financially, asked the American President Theodore Roosevelt to mediate peace. The peace treaty was signed in September of 1905 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.15

This was significant to Asian countries at the time because it was the first time in modern history that an Asian country had defeated a major power in Europe. This caused a shift in the balance of power during the first decade of the twentieth century. This became a global moment where the level of authority and structures began to be questioned in regards to the imperialist world.16 This historical moment of a Japanese victory over Russia was not taken lightly. Many researchers began to look at the significance of this war. This victory for Japan transformed the way many viewed Western civilization. It started an evaluation of the international order when it came to the non-Western world. Japan and its military were cheered on by Western media, and this led to great popularity in the Western part of the world. This was due to the underdog idea that many Americans had when it came to the Russo-Japanese War. Americans had been observing the war and began to both respect and find fascination in the way the Japanese military behaved. President Roosevelt’s attitude at the time was also in favor of the Japanese.17

This war symbolized a truly global movement, as a moment that would have a transformative impact for years to come. It moved anticolonial nationals to become more assertive and confident, strengthened the constitutional movement, and negated many views of European power holders.18

In conclusion, the Russo-Japanese War was a short, yet brutal war that tested the leadership and skills of both sides. Fortunately for Japan, they were better equipped in this circumstance. They had efficient commanders and prepared soldiers. With the help and leadership skills of Admiral Togo and his men, Japan was able to begin the war on a successful note that allowed them to set the pace for the rest of the war. Although Admiral Togo is not often recognized or credited, without his keen skills and insightful direction, Japan could have lost the war from the start.

- “Togo, Heihachiro | Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures,” Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures (website), accessed October 24, 2021, https://www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/e/datas/141.html. ↵

- “Togo, Heihachiro | Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures,” Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures (website), accessed October 24, 2021, https://www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/e/datas/141.html. ↵

- Ronald Andidora, “Admiral Togo: An Adaptable Strategist,” Naval War College Review 44, no. 2 (1991): 52. ↵

- Ronald Andidora, “Admiral Togo: An Adaptable Strategist,” Naval War College Review 44, no. 2 (1991): 53. ↵

- Ronald Andidora, “Admiral Togo: An Adaptable Strategist,” Naval War College Review 44, no. 2 (1991): 53. ↵

- Ronald Andidora, “Admiral Togo: An Adaptable Strategist,” Naval War College Review 44, no. 2 (1991): 54. ↵

- Yoji Koda, “THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR: Primary Causes of Japanese Success,” Naval War College Review 58, no. 2 (2005): 30. ↵

- Yoji Koda, “THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR: Primary Causes of Japanese Success,” Naval War College Review 58, no. 2 (2005): 29. ↵

- Ronald Andidora, “Admiral Togo: An Adaptable Strategist,” Naval War College Review 44, no. 2 (1991): 56. ↵

- T. J. Betts, “The Strategy of Another Russo-Japanese War,” Foreign Affairs 12, no. 4 (1934): 593, https://doi.org/10.2307/20030620. ↵

- Ronald Andidora, “Admiral Togo: An Adaptable Strategist,” Naval War College Review 44, no. 2 (1991): 56. ↵

- Yoji Koda, “THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR: Primary Causes of Japanese Success,” Naval War College Review 58, no. 2 (2005): 29. ↵

- Joel E. Hamby, “Striking the Balance: Strategy and Force in the Russo-Japanese War,” Armed Forces & Society 30, no. 3 (2004): 351. ↵

- Joel E. Hamby, “Striking the Balance: Strategy and Force in the Russo-Japanese War,” Armed Forces & Society 30, no. 3 (2004): 325. ↵

- Joel E. Hamby, “Striking the Balance: Strategy and Force in the Russo-Japanese War,” Armed Forces & Society 30, no. 3 (2004): 351. ↵

- Cemil Aydin, “The Global Moment of the Russo-Japanese War: The Awakening of the East/Equality with the West (1905–1912),” in The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia, Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought (Columbia University Press, 2007), 72. ↵

- Rotem Kowner, “Becoming and Honorary Civilized Nation: Remaking Japan’s Military Image during the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905,” The Historian 64, no. 1 (2001): 20, 37. ↵

- Cemil Aydin, “The Global Moment of the Russo-Japanese War: The Awakening of the East/Equality with the West (1905–1912),” in The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia, Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought (Columbia University Press, 2007), 72. ↵

10 comments

Mark Gallegos

I knew of the Russo-Japanese war and how Russia’s loss was seen as extremely humiliating due to how other European nations viewed Asian countries. However, I didn’t know what steps Japan took to claim victory. This article was very informative and well-written.

Samuel Vega

I enjoyed your selection and discussion of Admiral Togo and his role during the Russian-Japanese War. Your article covered an in-depth view of Admiral Togo’s background and how his training prepared him for prepare for the famous war. You showed how Admiral Togo deserves more credit for his “keen skill and insightful direction.” I was not aware of how this victory changed Western civilization’s view of Japan and how the media cheered Japan’s success.

Daniel Diaz

I had heard of Japan fighting Russia before but I had no idea it was the son of a samurai who had led that particular war. I suppose it was his efforts that gave Japan the boost in confidence that led to them committing atrocities during the second world war.

Rafael Macedo

This post does a fantastic job of summarizing the events. Tg Heihachir’s honorable acts were unknown to me, especially given the fact that he had studied in London and been taught the western style of naval warfare. It’s fascinating to consider that this defeat predicted the Russian army’s eventual failures in World War I to some extent

Phylisha Liscano

This was a well written article. I had very little knowledge of the subject before reading but I enjoyed getting the chance to read more about it. Taking a look I can tell lots of research was put into your article and you provided lots of information. Overall great article and an excellent topic. Good job, and congratulations for being nominated.

Christopher Metta Bexar

I had an interest in this article seeing as I had heard about the Japanese Navy in connection with the Sino-Japanese War as well as the Second World War.

I think it explains for me in part how Japan went from a nation in the shadow of the Chinese empires to a world class potential military predator.

I had heard after winning this war, so to speak, that Japan had went into empire building, attempting to conquer most of eastern Asia. We know that most of their military might in the Second World War came from the efficiency of their naval fleet.

Christopher Hohman

Nice article. I have heard of the Russo-Japanese War and the importance it had in shifting the power balance between Russia and Japan. It is also interesting that Togo was educated in European schools. I have read that the Japanese navy borrowed heavily from the British Royal Navy in terms of technology and strategy. I did not know that Togo was inspired by the tactics of Lord Horatio Nelson. This further demonstrates Japan’s use of European naval strategy. The Japanese navy established itself as a serious and modern navy from the Russo-Japanese War onwards, and I cannot help but feel that much of the skill and preparation carried over into the Second World War.

Santos Mencio

The Russ-Japanese War is one of my favorite conflicts in history to read about, and this article does an excellent job covering the events that unfolded. It’s interesting to think that this defeat foreshadowed to some extent the Russian army’s future failings in world war I. Being handily defeated by what could be considered as a second-rate military power should have given them more pause than it did. Instead, they fervently denied the defeat and ignored any possible lessons that could have been learned from the conflict.

Trenton Boudreaux

A very well written article on an underappreciated yet vastly important event in history. Had Japan lost the war with Russia, it’s likely that it would have never been able to become the economic powerhouse we know today. It’s surprising just how shattering of a worldview the Japanese victory was, which couldn’t have happened without the efforts of Admiral Togo.

Jourdan Carrera

This is a well written article which covers a subject that I did not know much about until now. The brave actions carried out by Tōgō Heihachirō was one that I did not know about, especially the fact that he had trained in London and was taught the western form of Naval warfare. I especially liked the fact that the author included the background thought done by the Japanese against the Russians, as up until now I did not know that there was that much thought put into it.