Imagine you are walking through your town, practically oblivious to the drama that is quickly unfolding, only to look up at Gallows Hill to see a supposed witch hanging from a tree. This could be enough to put someone into shock, but for the townspeople of Salem in 1692, this was about to become their new normal. The supposed witch that was hanging from the tree was Bridget Bishop, the first person to be hanged in Salem for witchcraft on June 10, 1692, but she would definitely not be the last.1

Before all of these accusations occurred, most townspeople in Salem lived somewhat average lives. Martha and Giles Corey were husband and wife who had a pretty decent life up until their accusations. Martha Corey was a member of their local Puritan church and actively attended church. Giles was Martha’s second husband after Henry Rich, with whom she had her second child, Thomas Rich. Her firstborn was an illegitimate mixed-race son who was raised by John Clifford of Salem until adulthood. Martha married Giles Corey on April 27, 1690, after her late husband, Henry Rich, had died sometime between 1684 and 1690.2 Giles definitely had a more complicated backstory than his third wife, Martha. Giles moved from Salem Town to Salem Village in 1659 with his first wife and the mother of his first four children, Margaret. Shortly after this move, Margaret died and Giles married Mary Bright in 1664. After twenty years of marriage to Giles and one child, Mary passed away in 1684. In 1690, Giles and Martha were married. Although Giles had been a well-respected farmer, there was an incident with Giles that led to his ultimate demise during the Salem Witch Trials. In 1676, Giles beat Jacob Goodale, his farmhand, to death with a stick. He was only charged a fine for this incident, but many believed that he paid a bribe for his freedom, which only led him to be more suspicious during the Salem Witch Trials.3

Essential to putting this story together is how the accusations against all of these women and men started. The accusations started after Reverend Samuel Parris moved into Salem Village in 1689 to be their first ordained minister for their church. In January of 1692, Elizabeth Parris, Reverend Parris’ daughter, and Abigail Williams, his niece, began behaving strangely. After an examination by their physician, their condition was blamed on witchcraft. Not too long after, Ann Putnam Jr., Mary Walcott, Elizabeth Hubbard, Mary Warren, and Mercy Lewis, who were all friends of Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams, started showing similar behavior. On February 29, 1692, these girls accused Tituba, Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborne as the women who bewitched them into this behavior.4

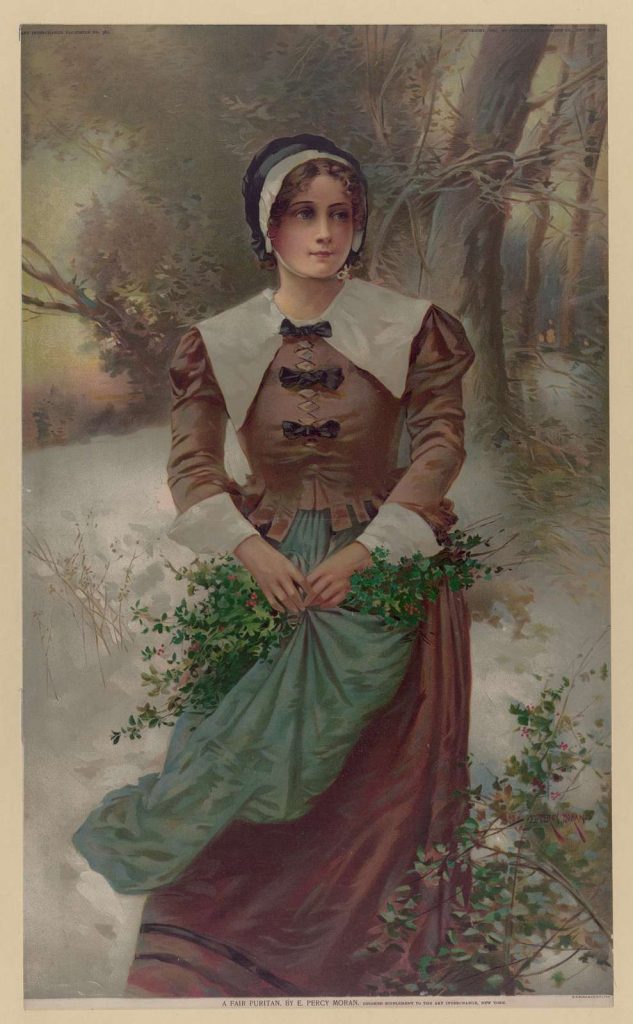

During the Salem Witch Trials era, most townspeople led very plain lives. Almost all had wooden houses that included a chimney in every room, and a kitchen with pottery and iron cooking utensils from their local blacksmith.5 The average man wore a puffy, long sleeve linen shirt with cuffs and a collar, a long coat, britches, stockings, leather shoes, and a broad-brimmed hat. The average woman wore undergarments, petticoats, long stockings, leather-heeled shoes, an outer skirt, a bodice, and a house cap.6 In this era, Puritans believed that it was important to create a domestic environment where the man was the “high priest” of the family. The wife played a supporting role who was in charge of the children, servants, domestic work, and all household activities.7 Many of these families living in Salem Village owned farms and made a living from their agricultural activity. Because of this, the majority of the families in Salem Village were very large and had their children do chores that would help them agriculturally.8 The church was a huge part of the lives of the Puritans of the era and attending the preaching on the “Sabbath Day” was crucial to their daily lives. Since attending Church and worshipping God were such important parts of their lives, even the mere thought of witches and the devil being in Salem was terrifying to them.9

Although the outbreak of accusations did not start in Salem, the Salem Witch Trials were much different than many earlier witch accusations in Puritan New England. The first execution of a witch was of Alice Young in 1647, forty-five years before the first accusations in Salem started. What made the Salem Witch Trials so renown compared to other executions for witchcraft, was the large scale of executions. Out of the one-hundred accusations before the Salem Witch Trials, there were only sixty trials and sixteen executions. The Salem Witch Trials alone had over two-hundred accused, jailed, and tried. Out of all of those, five died in jail waiting for a trial, nineteen were executed, and one person was pressed to death. This made the Salem Witch Trials known as one of the most unjust, vicious, and paranoid times in all of American history.10

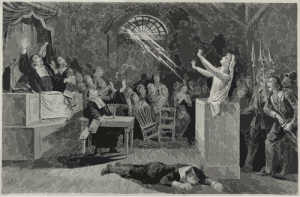

The majority of the women that were accused were unable to defend themselves, especially during their trials. During this time, a lawyer was not required to be assigned to the defendant, and the courts allowed “spectral” evidence to be admissible testimony. Spectral evidence is a type of eyewitness testimony where the witness sees the accused person’s spirit appear to the witness in a dream while the accused person’s body was at another place.11 Many of the accused women were middle-aged, usually widowed, with few to no children. They usually had no social status and were considered to be suspicious simply because they were not fulfilling normal female social roles. Some of the women who were accused had just come to own land and property on their own, which further challenged gender norms of their Puritan society. Since most of the women who were accused had no capable men to protect them from the accusations, they were seen as easy targets to win over their land or rid them from their town. This meant that many of the women never stood a chance against the tensions that they created over defying gender norms, so many of them were thought to be guilty of something even before the beginning of their trials.12

Martha Cory was accused of witchcraft on March 12, 1692 by Ann Putman Jr., who claimed that Martha’s spirit attacked her. This accusation came after Giles and Martha were attending some of the first examinations of Tituba, Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborne. Martha expressed her suspicions of the legitimacy of the claims and this caused tensions between her and the afflicted girls because they did not like anyone questioning their claims. Then, when Giles tried to watch another witch examination in town, Martha tried to convince Giles not to attend, going as far as to hide his horse saddle. This led to suspicions of Martha being a witch and the accusation from Ann Putman Jr., who was one of the afflicted girls who was accusing many women of witchcraft. This led to suspicions of Martha being a witch and the accusation from Ann Putman Jr., who was one of the afflicted girls who was accusing many women of witchcraft. After Ann’s accusation of Martha being a witch, many in town became worried because Martha held a high social status in the village and was a respected member of the church. Her being accused led to a widespread fear that now anyone could be accused of witchcraft, since Martha was seen as a respectable woman, unlike those who had been accused before her. Before filing an official claim against Martha, Edward Putman and Ezekiel Cheever decided to personally investigate the situation. They first went to Ann Putman Jr., to ask what Martha Corey had been wearing when she attacked her. Ann Putman Jr. claimed that during the attack, Martha’s spirit had temporarily blinded her, so that she could not see what Martha was wearing. Although Ann offered no proof, Edward and Ezekiel decided to go to Martha’s home. When they arrived, Martha said that she knew exactly what they were coming for. Then, to her demise, she asked if Ann told them what clothes she had on. Immediately, it was presumed that she had come to this knowledge of them asking Ann what Martha was wearing only by supernatural means.13

A warrant for Martha’s arrest was issued late in the day on Saturday, March 19. Due to it being late, there was not enough time in the day to act upon the warrant to arrest her and warrants couldn’t be fulfilled on Sundays, so she stood her ground and went to church on Sunday. But on Monday, March 21, Martha was taken to the courthouse to be examined for witchcraft by Judge Hawthorne. He asked her many questions about how she knew that Edward and Ezekiel came to ask her about being a witch and if Ann had told them what clothes she was wearing, which she knew because Giles had told her that during other examinations, they had asked the afflicted girls what the attacker was wearing to prove themselves in court. Judge Hawthorne also asked Martha why she tried to stop Giles from attending examinations, but like many other trials, they wouldn’t believe a word and she stood no chance. Any time she tried to answer a question, Hawthorne accused her of lying. When she made any movements, the afflicted girls had fits like they were being tortured by her. Hawthorne tried to convince Martha to admit guilt over practicing witchcraft, which would have kept her alive, but she refused. Although she maintained claims of innocence and being a gospel woman until the end of the examination, Martha was still charged with two counts of witchcraft against Mercy Lewis and Elizabeth Hubbard. After the examination, she was sent to jail in Salem to await her trial. Later, Martha was moved to a jail in Boston due to overcrowding from the large numbers of accusations in Salem.14

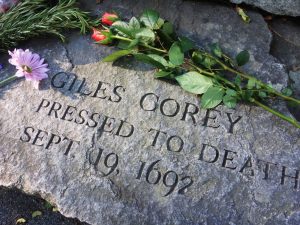

After Martha’s examination, on March 24, Giles Corey committed the biggest act of betrayal and testified against his wife, saying that their ox and cat suddenly became sick out of the blue. He also claimed that Martha would kneel in front of the fire and pray, but he never heard her praying. He also didn’t help his wife by admitting that he told her about the court asking the afflicted girls what their attacker was wearing when she claimed that he told her about this during his attendance at other examinations. But his cooperation with the court ceased on April 18, when an arrest warrant was issued against him. Many of the afflicted girls, like Mary Walcott, Ann Putman Jr., Abigail Williams, Elizabeth Hubbard, and Mercy Lewis all accused Giles of using witchcraft against them. During his examination, he was repeatedly accused of lying by Judge Hawthorne and Judge Corwin, proving that he didn’t stand a chance against the court, just like his wife. They also tied his hands together to prevent him from practicing witchcraft and every time they untied one of his hands, the afflicted girls would have fits, just like when Martha tried to move during her examination.15 After his examination, Giles was officially charged with witchcraft on September 16. He pled not guilty and refused to submit himself to the court for a jury trial. He was silent during his trial, which brought it to a standstill. Since he was unwilling to cooperate with the court, he was sentenced to undergo the torture of “pressing.”16

On September 17, 1692, Giles Corey was taken to an empty field near Salem jail, undressed, put on his back, and tied to the ground. Then, wooden beams were placed across his chest and heavy stones were placed on top of the beams. On September 19, 1692, after Sheriff Corwin complied with Giles’ request for more weight, the weight of the stones crushed his rib cage and he died. Many believe that Giles died instead of admitting guilt because he knew he was going to be executed one way or another. In light of this, not admitting guilt allowed him to pass all of his estates down to his children.17 Although Martha was arrested in March, her official trial was delayed by the court numerous times because they knew it would take a great deal of evidence to convict her, since she was a woman of high status. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what happened; many witnesses testified against Martha, building a solid enough case to convict her. On September 8, 1692, Martha Corey was found guilty of witchcraft and was sentenced to death. On September 22, 1692, Martha was brought to Gallows Hill with seven other convicted witches and was hanged.18

The Salem Witch Trials came to an end on October 29, after Cotton Mather, a minister of high esteem, urged the court to no longer use spectral evidence as proof of one’s guilt. Eventually, all the accused were pardoned from jail by May 1693, but that wouldn’t make up for all of the lives that had been lost.19 On October 11, 1711, Martha, Giles, and 20 others had their names cleared and their heirs received 21 pounds in financial compensation. Martha’s son, Thomas, 50 pounds on June 29, 1723, as restitution for his mother and step-fathers death. Although their guilty verdicts had been cleared in 1711, it took exactly 300 years after Martha and Giles’ deaths in 1692 before their excommunication from the church was lifted in 1992. The Salem Witch Trials are studied thoroughly today due to the mystery around the motives behind the afflicted girls accusing anyone and everyone. Although there are many theories about why it happened, it doesn’t take away from the fact that it was a time where neighbors turned their backs upon one another. Although it was eventually stopped, and everything seemed back to normal, for those who had lost their innocent loved ones, it would never be the same.20

- K. David Goss, The Salem Witch Trials: A Reference Guide: A Reference Guide (Westport, Conn: Greenwood, 2008), 85-86. ↵

- Rebecca Brooks, “The Witchcraft Trial of Martha Corey,” History of Massachusetts (blog), August 31, 2015, https://historyofmassachusetts.org/martha-corey/. ↵

- Rebecca Brooks, “The Witchcraft Trial of Giles Corey,” History of Massachusetts (blog), October 12, 2011, https://historyofmassachusetts.org/the-curse-of-giles-corey/. ↵

- Joshua Mark, “Salem Witch Trials,” World History Encyclopedia, April 13, 2021, https://www.worldhistory.org/Salem_Witch_Trials/. ↵

- K. David Goss, Daily Life during the Salem Witch Trials, The Greenwood Press Daily Life through History Series (Greenwood, 2012), 51-55. ↵

- K. David Goss, Daily Life during the Salem Witch Trials, The Greenwood Press Daily Life through History Series (Greenwood, 2012), 57-62. ↵

- K. David Goss, Daily Life during the Salem Witch Trials, The Greenwood Press Daily Life through History Series (Greenwood, 2012), 62. ↵

- K. David Goss, Daily Life during the Salem Witch Trials, The Greenwood Press Daily Life through History Series (Greenwood, 2012), 69-70. ↵

- K. David Goss, Daily Life during the Salem Witch Trials, The Greenwood Press Daily Life through History Series (Greenwood, 2012), 109-112. ↵

- K. David Goss, Daily Life during the Salem Witch Trials, The Greenwood Press Daily Life through History Series (Greenwood, 2012), 41. ↵

- “Spectral Evidence,” Salem Witch Museum, February 15, 2013, https://salemwitchmuseum.com/2013/02/15/spectral-evidence/. ↵

- Alan Brinkley, American History, 15th ed., vol. 1: to 1865 (2 Penn Plaza, New York, NY 10121: McGraw Hill Education, 2015), 86-87. ↵

- Rebecca Brooks, “The Witchcraft Trial of Martha Corey,” History of Massachusetts (blog), August 31, 2015, https://historyofmassachusetts.org/martha-corey/. ↵

- Rebecca Brooks, “The Witchcraft Trial of Martha Corey,” History of Massachusetts (blog), August 31, 2015, https://historyofmassachusetts.org/martha-corey/. ↵

- Rebecca Brooks, “The Witchcraft Trial of Giles Corey,” History of Massachusetts (blog), October 12, 2011, https://historyofmassachusetts.org/the-curse-of-giles-corey/. ↵

- K. David Goss, The Salem Witch Trials: A Reference Guide: A Reference Guide (Westport, Conn: Greenwood, 2008) 89. ↵

- K. David Goss, The Salem Witch Trials: A Reference Guide: A Reference Guide (Westport, Conn: Greenwood, 2008) 89. ↵

- K. David Goss, The Salem Witch Trials: A Reference Guide: A Reference Guide (Westport, Conn: Greenwood, 2008), 90. ↵

- Smithsonian Magazine, “A Brief History of the Salem Witch Trials,” Smithsonian Magazine, accessed October 29, 2021, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/a-brief-history-of-the-salem-witch-trials-175162489/. ↵

- K. David Goss, The Salem Witch Trials: A Reference Guide: A Reference Guide (Westport, Conn: Greenwood, 2008) 90. ↵

52 comments

Ki' Asya Jackson

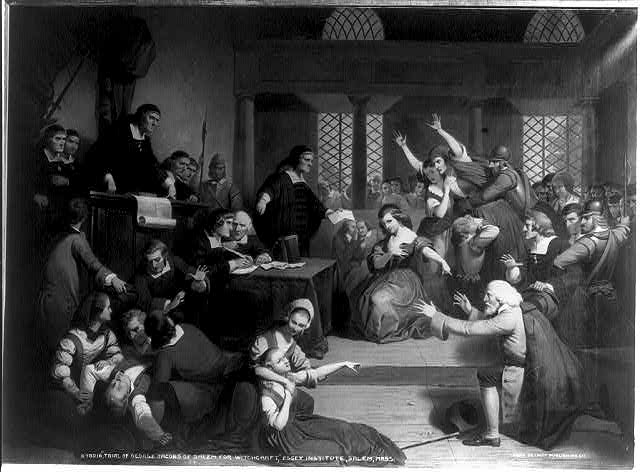

I enjoyed how the author used diction to create an image of what the new norm in Salem looked like. I also enjoyed the background information given so that later in the article, it can be understood what led to the witch trials. One more thing I enjoyed in this article was the placement of the selected images since they add to the story of what Salem Village went through and how it was remembered. It was very informative for those who may want to start looking into the Salem Witch Trials.

Matthew Gallardo

The story of the Salem witch trials just becomes more and more insane the more I learn about it. I had no idea one of the accused had their own Husband testify against them. The fact that this just kind of became normal for people to be accused of witchcraft is also saddening. I’m glad however to know that someone eventually stepped in and convinced the court to stop going off of spectral evidence.

Gisselle Baltazar-Salinas

This article really had me thinking and reflecting a lot on our history and the mistakes that were made. It is sad to think that there was nothing done or said to the families that lost sisters, mothers, friends or grand mothers to fear. Although this was not mentioned in the article, the way they conducted the trails was rigged against all the women. For instance, they would determine if you were a witch if you could swim. Either way you’d parish so not really a fair trail there. Really a sad part of our history and crazy to think how little it is recognized and talked about.

Carlos Hinojosa

This was a very good article and I think conveyed what the author was trying to tell very well. I remember watching a documentary about drugs and the scientists can to the conclusion that bad bread infected with a fungus that caused the Salem crisis because the fungus makes you hallucinate. So, I thought that was interesting.

Charles Lares

As someone who’s very interested in the topic of the Salem Witch Trials, I was thrilled to have read your article. The in-depth information that you put into your article had broaden my knowledge of these important men and women who were accused during the trials. I specifically liked how you explained how fast things can change in such a short time especially for the young women in Salem. After reading your article, it’s clear that the accused women of witchcraft were people of low status or those who weren’t married that made them vulnerable to accusations and execution. It’s crazy to see how an accusation could cause such damage to happen to a person. The trials were unjustified and unnecessary due to the lack of evidentiary support used in court.

Madison Goza

I greatly enjoyed reading your article about the Salem Witch Trials! I really liked that in your introduction you speak to the reader directly to imagine themselves coming across the sentencing of an accused witch. It immediately caught my attention and made me want to read more. I also appreciate the time you spent to describe and explain what life was like during this time; it helps to put in context these horrible tragedies. Great article!

McKayla Rodriguez

This article was so interesting! The Salem Witch Trials have always been something I’ve been wanting to learn more about. It was so intriguing to have a glimpse in the history of witches in Salem and New England. Many women, who could’ve been innocently accused were blamed for witchcraft with no support system, and so many lives were lost through cruel deaths, which were unfortunate.

Alonso Rodriguez

Witch hunts were commonplace at the time. In Europe, the Inquisition tried to eliminate them en masse, but there were members of the institution who were not driven by ecstasy and madness, but had common sense, claiming that there was always a lack of evidence, or that the first witnesses of paranormal events were always children, who tend to have an inordinate imagination. Very interesting this article, because not everybody knows about this subject.

Isaac Fellows

Wow. What a moment in time this was, for real. To think that actual people were spurred into such mania is crazy to think about. It was especially shocking to read about Giles Corey getting crushed to death– like the people of Salem meant no joke. I enjoyed this article, as despite Salem being such well known event in today’s culture (especially since it appears in so many forms of media nowadays), I knew very little about what actually happened. This was a well done article!

Isaac Fellows

Also that title was uncalled for, haha.

Andrea Moreno

This article did a great job explaining the events of one of the most famous events in American history. Seeing how the trials disproportionately affected women due to the patriarchal imbalance was just as upsetting as it was eye-opening. The events of the trials can get caught up in conspiracy theory and speculation but it is important to remember the lives lost due to the false accusations.