Dolly is no doubt one of the most well-known sheep in the entire world. She has flipped the whole science world on its head and made scientists question the boundaries that they had never dared to try and pass. Her birth brought about a new era in the world of science, and with it many challenges and further discoveries. In the early 1900s, the idea of cloning was barely even a thought. Scientists had experimented with the cloning of younger animals, where they had experienced limited success, but they had set a new goal in which to learn how to clone an adult mammal. This task was seen as somewhat fantastical and hopelessly out of reach with the technologies of the time, if even possible at all. Several attempts had been made, and small discoveries slowly began to trickle into the scientific world, but it wasn’t until 1935 that one man’s crazy ideas got some serious recognition.

Hans Spemann, a German experimental embryologist, worked for years to develop what he came to coin “The Organizer Effect.” In his many experiments with the epidermis, eyeballs, and embryos of amphibians, he came to discover that a cell extracted from one animal and injected into the cell of another can influence the way that the recipient animal develops. Spemann tested his theory on a simple tadpole, and his result was, of course, another tadpole, but with an astounding two heads! He described this concept of one cell influencing the growth of another as induction. Spemann’s theory of induction was groundbreaking and led scientists to ponder whether or not extracting the nucleus from the cells would have the same result. This nuclear transfer is used in the current cloning process, and without Spemann’s foundational ideas, it would have been difficult for scientists to progress as quickly as they have been. The cell in which the new cell is introduced is what is know as “the organizer” because it is able to restructure the information that was already in the cell in the first place. After long hours of extensive research in Germany, and the onlooking pressure from fellow scientists, Spemann’s work finally got the attention it deserved. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1935 for his discoveries, and his work became very influential in his field of study.1

For a little over fifty years, the cloning scene laid low. There were no more major advancements like those of Spemann in the early 1900s. That is, until biologist Keith Campbell and embryologist Ian Wilmut came along. In 1996, the two scientists began their work at the Roslin Institute in Scotland, where they based their research and lab procedures on the Nobel Prize winning ideas of Hans Spemann, and his induction and cloning mammal research.2

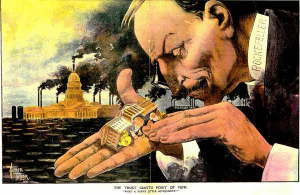

As cloning research began to increase, many scientists, and others, began raising ethical concerns about where this research was heading. Scientists began to predict where the industry could go in the future and the effect that it could have not only on animals, but on humans as well. While cloning did seem promising at its early stages, scientists could not help but think of human cloning in the future and the major ethical concerns that would come along with it. The public’s ideas generally weren’t derived from a more positive view. In their minds, they saw “Designer Babies,” and imagined how the wealthy would soon be able to manipulate the gene structure of an embryo to produce a smarter, better-looking, more-talented child. As a result, the existing gap between the rich and the poor would become even more dramatic.3 Not only that, but it wasn’t long ago that the public witnessed the destructive tests and extensive research that went into cloning animals along with the countless failed attempts that resulted in mutations or death of the offspring. In the cloning of humans, scientists expected to see comparable results of mutation and death.4

Major figures in the 2000s voiced concerns on both sides of the cloning debate. Former First Lady, Nancy Reagan, was among the smaller group that was able to see the potential benefits that cloning offered the world, specifically in that cloning could help in the curing of currently terminal diseases. She said, “Science has presented us with a hope called stem cell research, which may provide our scientists with many answers that for so long have been beyond our grasp. I just don’t see how we can turn our backs on this.”5 On the other hand, President George W. Bush voiced the opposing view that had concerns about cloning and its uses. He addressed the issue saying, “Make no mistake, that a cluster of cells is the same way you and I… started our lives. One goes with a heavy heart if we use these [embryonic cells]… because we are dealing with the seeds of the next generation…I believe all human cloning is wrong, and both forms of cloning ought to be banned.”6 President Bush was concerned about the manipulation of the genetic code and the way that it could change the coming generation. The bold statements and opinions from political figures such as these had a major impact on the views of the general public, but the overwhelming disapproval of cloning made it even more difficult for scientists to develop an effective process.

While this broad disapproval of cloning clouded the efforts of scientists interested in researching cloning, Campbell and Wilmut continued their research in order to achieve their goal of cloning an adult animal. They employed a newly developed process called Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT), in which they extracted the nucleus of a single somatic cell, or an adult cell of an animal, from the animal they want to clone, and then inject it into the unfertilized egg of another cell with the nucleus removed. In 1997, the two scientists began the SCNT process with a cell from an adult female sheep. After a few days, they implanted the cell into another female sheep, hoping that the cell would be accepted in her system and that a birth from it would be successful. Without knowing whether or not they would be successful, and with 276 failures behind them, the chances looked slim, but they decided to give it a try and hope for the best.7

As can be expected, the world’s view of cloning was not more accepting as the experimentation continued. Many felt that something had to be done to stop these experiments from becoming accepted. One of the newest developments in the cloning world was chimeras, or organisms consisting of more than one set of genes. Chimeras are animals that have been experimented on and now contain some human DNA in their systems. One of the main reasons for this process is to test whether or not human diseases can be effectively cured or improved with experimental treatment options before they are released to the public for use. In this way, scientists are creating animals and changing them to have more human characteristics. A past member of the President’s Council on Bioethics, Alfonso Gomez-Lobo, commented on chimeras saying that they, “violate the sanctity of human life by mixing humans with animals,” and that, “What is essentially human is really debased.”8

In 2009, San Brownback and Mary Landrieu, two senators, attempted to introduce a law that would completely stop the chimera testing processes all together. The supporting views of the public against chimeras gave the two a strong backing, and they hoped to bring about a drastic change. To stop what they deemed an immoral practice, they decided to create and propose a law to Congress that would prohibit all further testing similar to those of the chimeras. Although they had support, their law was never passed, but they are hopeful that it will be reconsidered at some point in the future.9

With the continuing turmoil, Wilmut and Campbell waited anxiously to see if their SCNT test on the female sheep would turn out to be a success. Everything seemed to be against them, but luckily enough, science was on their side. On July 5, 1996, their troubles were turned into triumph with the birth of a new baby sheep. Named after famous country singer Dolly Parton, Dolly the Sheep became the first mammal ever to be cloned from the cell of an adult animal.10 While the cloning was effective, the scientists were hesitant to share their results, in fear that Dolly’s life would be cut short due to some unforeseen problem in her production. Because of this, they waited almost an entire year, until, February 22, 1997, to announce the results of their tests. After the announcement, the news spread quickly. Dolly was featured in the Times and Science magazines, and she earned a sort of recognition that made her known all around the world.11

While many people emphasize the negative results of cloning, there are potential benefits as well. Scientists have suggested, for example, that the organs of pigs are compatible to those of human beings. This means that their organs could be harvested for therapeutic use in humans.12 Another area in which scientists have continued their research is in that of gene therapy, in which they use stem cells to control diseases like Parkinson’s and diabetes. While cloning doesn’t cure the disease, it can help to control it in both current and future generations.13 Along with the possibility of saving people’s lives, cloning can also help to save an entire species of animals. By taking the genes and DNA from an endangered species, scientists can have the species live on forever. Also, being that the cloning process doesn’t require a male and a female, it is more reliable in the case that one of the two dies out.14 In light of all of this research, most people see only a fine line between the scientific and religious obligations that come along with the cloning process. While cloning may be able to help cure diseases and save lives, it can also be manipulated and result in the destruction of life through the many experimental tests that are required for success.

Incredibly, Dolly the Sheep lived to be almost six and a half years with a reputation like no other. During this time, she broke the boundaries of what scientists had known and had come to expect, and she set the limit high for all those scientists to follow in the future. As Dolly became older, so did her frame and her health and she began to deteriorate. She developed arthritis and a form of lung cancer, and, in the end, she had to be put down. Even though she’s gone now, Dolly will continue to be remembered and her impact will always be felt forever around the world.

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, “Hans Spemann.” ↵

- Anna Marie Eleanor Ross, Scientific Thought: In Context (Detroit: Gale, 2009), 527. ↵

- Tina Kafka, Cloning (Detroit: Lucent Books, 2008), 78. ↵

- Barbara Wexler, Genetics and Genetic Engineering (Detroit: Gale, 2014), 135. ↵

- Carla Mooney, Bioethics (Detroit: Lucent Books, 2009), 81. ↵

- Carla Mooney, Bioethics (Detroit: Lucent Books, 2009), 88; Melissa Abramovitz, Stem Cells (Detroit: Lucent Books, 2012), 75. ↵

- Biotechnology: Changing Life Through Science, 2007, s.v. “Animal Cloning.” ↵

- Melissa Abramovitz, Stem Cells (Detroit: Lucent Books, 2012), 72-73, 75. ↵

- Melissa Abramovitz, Stem Cells (Detroit: Lucent Books, 2012), 76. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Science, Technology, and Ethics, 2005, s.v. “Human Cloning,” by Glenn McGee. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Communication, 2010, s.v. “Cloning,” by Rödder, Simone. ↵

- Richard Gray, Roger Dobson, and Kenneth Travis LaPensee, Biotechnology: In Context (Detroit: Gale, 2012), 247. ↵

- Kate Sampsell, History Behind the Headlines: The Origins of Conflicts Worldwide (Detroit: Gale, 2003), 78. ↵

- Environmental Encyclopedia, 2011, s.v. “Cloning,” by Ken R. Wells. ↵

77 comments

Greyson Addicott

What a very strange subject to read about! I can still fondly remember the time that our class was taught about Dolly the sheep. To my dismay, the subject of cloning seems to be relatively silent upon the world stage. I suspect that the silence over the subject is anything but natural, and is instead a result of the competition certain firms experience when dealing with the matter, or, alternatively, the silence arises from a specific federal or legalistic restriction, much like the Manhattan Project of old. The morality of the absence of news over cloning is unquestionably something to be debated, but it is nevertheless a pity that scientific talks about induction have, for the most part, been absent.

Lyzette Flores

Many scientists at first are always looked as crazy or crazy for their ideas. I am glad that Hans Spemann continued on with his discovery because that influenced other scientists to further on with the discovery. Every day there are new things being shown and brought into this world. As the article stated, everybody has different opinions on cloning. Some say it will cause negative outcomes but honestly, I feel as it will bring more positive outcomes.

Enrique Segovia

Great article! I had previously heard of Dolly the sheep many times before, but I consider this article did a great job in explaining in detail the process and the obstacles faced to clone an animal. It is truly impressive how far science has gone, taking into account that just by taking cells, we can now clone mammals. However, as marvelous as this may be, I think it also poses a new risk that humans have to be careful with. This article made me ponder about the distinct challenges that cloning mammals might bring in the future.

Mariana Valadez

I had never heard about Dolly the Sheep before. It is very interesting to see this science experiments, but it makes me have a lot of ethical questions. I don’t believe cloning could be good in humans. This article was very well written overall. It left me a bit confused about the whole scientific side of it. Very Good article!

Christopher Vasquez

Dolly the sheep, as well as the organizer effect, makes me wonder what the ethical guidelines regarding cloning are. Having two heads, especially as depicted by the dog picture above, and no father but three mothers make me think that we are heading down a slippery slope. I do think that the concept of cloning is interesting, but, in practice, it appears that it may decrease the quality of life of individuals. If the idea ever comes to humans, I think that there will most definitely be ethical questions that need to be answered. Thank you for this article!

Christopher Hohman

Nice article. I had heard of Dolly the sheep before. What an incredible thing those scientist accomplished. She really was a step an interesting direction. I understand however that many people are opposed to it on religious grounds. That is really interesting because there are many scientist including the late Stephen Hawking who are opposed to it as well. Hawking, in his last book, warned us that cloning could lead to genetic manipulation. I think that we are still ages away from being able to clone humans, but I am unsure if we should.