Winner of the Fall 2019 StMU History Media Award for

Best Overall Undergraduate Research

“I have proved and believe that change is possible even after a long period of uncertainty, challenge, isolation, despondency, rejection, hopelessness, and anger,” said Jane.1 Jeanne “Jane” Mukuninwa was born in the village of Lulingu, in Shabunda Democratic Republic of Congo sometime in the 1990s.2 She lived in her village with her parents and was a little girl full of joy, innocence, and freedom. Before the civil war, she played with other children under the rain, went to the river and the farmlands, and ran through the streets with no fear. Jeanne and her family were safe and lived in peace. One of the few problems she experienced before the war was lack of education, and like many her age, she was not able to read or write.3 However, this problem was nothing compared to what was to come. At fourteen years old, her entire life was transformed by the horrors and darkness of the civil war.

The civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was and is a regional conflict that began in 1994 and officially ended in 2003, but political, social, and economic issues have been ongoing. This conflict began in an aftermath of the Rwandan genocide when the Ugandan and the Rwandan governments invaded the DRC in 1996 with the intention to terminate the refugee génocidaires that were living in eastern Congo. The outcomes of this war, referred to as the First Congo War, were that Uganda, Rwanda, and the Congolese opposition leader Laurent Désiré Kabila would overthrow the DRC dictatorship government of Mobutu Sese Seko. Nine African countries were involved in the Second Congo War and because of this, it is better known as The African World War. The Second Congo War lasted five years and was one of the deadliest international conflicts since World War II. This war was caused when the new government of the DRC feared that Uganda and Rwanda were going to take control of the mineral resources of the region, and asked them to leave Congo. Instead of leaving, these groups united forces with militia groups and caused harm to the civilians and killed the president of Congo at that time, Kabila (father). In 2002, two peace accords were signed by Congo, Uganda, and Rwanda.4 However, the domestic issue inside Congo was not finished. This was the cause of displacement, immigration, disease, and sexual violence throughout the country. Even though the DRC is the richest country in the world when talking about its mineral resources, it has become a place in which its people are among the poorest in the world. From 1993 to 2003, tens of thousands of people were killed, and numerous others raped and mutilated by both Congolese groups and foreign military forces.5 Approximately 200,000 women and girls were assaulted, with the north-eastern provinces of DRC being the most affected areas and girls ages ten to seventeen years old being the most vulnerable.6

When Jeanne was fourteen years old, she became an orphan due to her parents’ disappearance in the middle of the civil war conflicts, and their bodies were never found. They were presumably massacred during the fighting, and Jeanne never saw them again. As a consequence of this, she moved with her uncle from her mother’s side of the family and his family. Immersed in deep pain since the loss of her parents, she didn’t know that this was just the beginning of her suffering. Before the war, she did not know the meaning of the word “rape,” but soon after the rumors from other villages about it started to increase, fear came over her and other women. Shortly after she moved in with her uncle, the Hutu militia attacked her village. The family was inside the house when they heard some commotion outside and locked the door for security. Since the door was not strong, the militia broke it down and went inside the house. The Hutu militia stole everything that was in the house of value and made them walk and carry the things for days. If any person in the group complained about anything they were killed instantly.7 This day, the militia not only stole their belongings, but also brutally tortured her uncle by cutting off his hands, gouging out his eyes, cutting off his feet, cutting off his sex organs, and then just left him like that. He was still alive.8 After that, the militia kidnapped her aunt, cousin, and her. Jeanne Mukuninwa remembered clearly; that was the day of her first and last menstrual period. After that day, she understood clearly what the meaning of the word rape was.

“Rape is a weapon even more powerful than a bomb or a bullet. At least with a bullet, you die. But if you have been raped, you appear to the community like someone who is cursed. After rape, no one will talk to you; no man will see you. It’s a living death.”9 Sexual violations have a negative and destructive effect on families, affects people physically, psychologically, and increases the propagation of diseases among the population. In the DRC, rape is used as a war weapon and its victims struggle each day to have rehabilitation. Mass rape is a key weapon in this conflict since the different militia groups utilized it to silence the people, control communities, territories, and natural resources. Since the act of raping a woman terrifies her, humiliates husbands and fathers, and makes the family feel less and weak, it is used as a tool to coerce entire communities into silence. Also, in many of these communities, the women that are raped become rejected by men or even expelled from the community. Through silencing the community, the militia groups gain security, authority, and domination, and justice is made almost impossible. Studies confirm that sexual violation rates are higher in areas where there are mineral resources available. This means that through sexual violations, the community is weakened, and it is easier to control its natural resources. Other reasons why sexual violations are used as a tactic of war in the DRC are as spiritual rites, to humiliate, terminate pregnancies, increase food insecurity, express frustration and anger, and retaliate. Sexual violations are “cheaper than bullets, and more destructive in many cases.”10 In one attack in April 2018 committed by the Mai-Mai militia, at least sixty-six women, eleven girls, and two men were raped and gang-raped. Mass rape is a continuous menace to the DRC’s public health since approximately 1994. According to the United Nations’ Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), in 2018 there were 1,049 cases of conflict-related sexual violence against 605 women, 436 girls, 4 men and 4 boys.11 Sadly, these numbers can increase if governmental institutions do not do something to stop this.

When people were captured by the militia, if they were men, they were most likely trained to be porters, and if they were women like Jeanne, they were used to cook and as sex slaves. Any man could countlessly rape her, and sometimes she was even raped by rifles and sticks.12 Constantly, Jeanne and other girls were tied spread-eagle and gang-raped; consequently, Jeanne quickly became pregnant. Since her body was not prepared to receive the baby, a doctor, who had been kidnapped by the militia, opened her by cutting into her stomach without anesthesia or disinfected utensils, in order to save her life. After taking out the dead baby, parts of the baby’s body remained inside of Jeanne. Because of this, her uterus was decomposing and made her produce a foul smell that permeated through her mouth and genitals. Jeanne was no longer useful as a sex slave, and the militia threw her to the street, almost dead. Walking alone while almost dying, she managed to get to the Panzi Hospital, where Dr. Mukwege performed nine surgeries to save her life and her reproductive system. The Panzi Hospital is a foundation that earned global recognition as a treatment center for victims of sexual violence in conflict. Dr. Mukwege is the foundation’s director and a gynecologist who gained worldwide recognition and received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018.13

After surgeries and recovery, Jeanne returned to her village with hope; however, that hope was soon destroyed. The militia returned to her village and raped her again. She was left naked in the forest for days until she found her way back to the Panzi Hospital.14 People routinely came to see all the sexual violence victims at the hospital. Because of this, Jeanne, together with other women, “felt humiliated [when] being filmed and photographed like animals in a zoo.”15 However, one day a woman named Eve Ensler went to the hospital and asked the victims what she could do to help. Hopeless and without trust in the promises made by Eve Ensler, these women answered that they wanted a place where they could feel secure, heal, tell their stories and be empowered.16 These women, Jeanne included, wanted a place of refuge for their bodies and their souls. Actually, Jeanne was the one that spoke up for all the women in the group. This conversation with Eve Ensler changed everything in Jeanne’s life and birthed a place of restoration, the foundation, City of Joy.

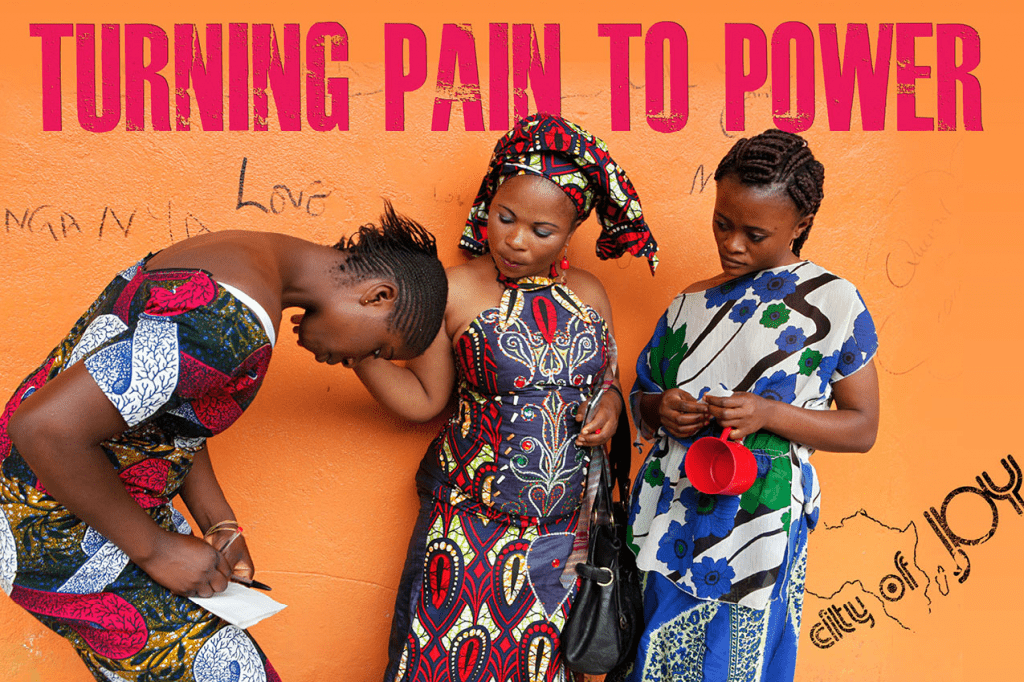

The sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo is a consequence of the economic disaster that began in 1996 and produced the Civil War. Tunataka nini?…Tunataka nyumba na amani. What do we want? We want a home and peace.17 Women were afraid of returning to their communities after what they experienced, so they asked for a home and peace. Founded in June 2011, the City of Joy in the Democratic Republic of Congo is a non-profit organization made, owned, and run by local Congolese people. The purpose of this organization is to empower and rehabilitate victims of sexual violence. The organization is located in Bukavu, Eastern DRC, and has aided over 1,200 women.18 Jane calls the City of Joy a place where joy, self-confidence, love, hope, and ferocity are regained after a period of trauma, isolation, despair, and uncertainty.19

Programs like the City of Joy are examples of non-governmental organizations that address public health issues where governments lack the ability to respond and act. Non-governmental programs like this one are mainly funded by donations from individuals and professionals like gynecologists and advocates against sexual violence. In the case of City of Joy, Dr. Denis Mukwege and Eve Ensler, an American feminist activist are primary donors. City of Joy works to improve public health within the DRC by providing education, psychological help, gynecologists, and self-defense training. This community is called the City of Joy because, according to Jeanne, “Women who come from their villages carry a burden of trauma and are unable to speak. Many believe they have lost hope and can’t do anything better. When they enter the City of Joy, they start breathing the air of joy because they are embraced. They smile for the first time after they have been assaulted and they find people who want them to feel at ease.”20 The City of Joy serves ninety survivors of gender violence from ages eighteen to thirty. For each six-month period, the City of Joy offers an intense program of education and training where women learn valuable life skills like agricultural knowledge, reading, writing, self-defense, and many more.21 The City of Joy believes women are not victims; rather, they are survivors, and each woman is valuable to her society no matter what they experienced. Women have the right to be treated with dignity and each woman is capable of activating their own recovery process.22 In 2016, City of Joy had the opportunity to create a Netflix documentary film called The City of Joy. This film told the story of the first class of graduates from the City of Joy in 2011.23

When Jeanne first came to the City of Joy, she felt happy and understood. There were people who cared about her. Before the City of Joy, she felt as she was the only woman that had experienced sexual violation; however, at the City of Joy, she heard other women’s testimonies and identified with them. Thanks to this, she understood that she was not alone and that each one of the sexual violence survivors had a unique story. Jeanne became a first-generation graduate from the City of Joy in December 2011. Though Jeanne experienced a very difficult time of torture and rape, after the rehabilitation program of the City of Joy, she was transformed into a totally new person. She transformed her “Pain to Power” like the lemma motto of the City of Joy says, and was able to become a leader to her community and to the City of Joy.24 The change in her life was so significant that she decided to change her name from Jeanne to Jane. She changed her name because of her transformation in the program. “Old Jeanne was full of self-pity, hatred, and suffering. New Jane is independent, young, and a leader.”25

The City of Joy taught Jane to count money, read, sew clothes, write, and even learn English. Presently, Jane works as a staff member at the City of Joy and was part of the 2016 Netflix documentary about the story of the City of Joy and its role in changing and empowering women’s lives. Jane has become an activist and leader for her Congolese community. She wrote two blogs about the V-DAY movement (to end violence against women) in Rise for Justice, which is an international movement that advocates for justice against sexual violence.26 Jane is an instrument of change, and an example and a voice to everyone who experienced the horrors of sexual violence. Being part of the program of the City of Joy allowed Jane to recover her self-love and self-acceptance; she understands that she is a beautiful human being and what she experienced with sexual violence does not change her essence. She declared in an interview with Art at Harvard University, “love has more power than medicine to heal people who have been traumatized and rejected by their communities.”27

- Jane Mukuninwa, “Congo Rising: Why am I Rising for Justice,” One Billion Rising (blog), January 17, 2014, https://www.onebillionrising.org/4467/rising-justice-jane-mukuninwa/. ↵

- Jeanne Mukuninwa, “Congo Rising: Why am I Rising for Justice,” One Billion Rising (blog), January 17, 2014, https://www.onebillionrising.org/4467/rising-justice-jane-mukuninwa/. ↵

- Lyneoyugi, “How Militia Rape me and Tore me Apart,” Lyneoyugi (blog), March 25, 2013, Lyneoyugi, https://lyneoyugi.wordpress.com/2013/03/25/how-militia-raped-and-tore-me-apart/ ↵

- “ About DRC: History of the Conflict,” Eastern Congo Initiative (website), http://www.easterncongo.org/about-drc/history-of-the-conflict ↵

- “DR Congo: UN Releases Most Extensive Report to Date on War Massacres, Rapes”, October 1, 2010, United Nations News (website), https://news.un.org/en/story/2010/10/354522-dr-congo-un-releases-most-extensive-report-date-war-massacres-rapes ↵

- UNFPA, “Secretary-General Calls Attention to Scourge of Sexual Violence in DRC”, March 1, 2009, United Nations Population Funds (website), https://www.unfpa.org/news/secretary-general-calls-attentionscourgesexual-violencedrc ↵

- Lyneoyugi, “How Militia Rape me and Tore me Apart,” Lyneoyugi (blog), March 25, 2013, Lyneoyugi, https://lyneoyugi.wordpress.com/2013/03/25/how-militia-raped-and-tore-me-apart/ ↵

- Nicholas Kristof, “The world Capital of Killing,” February 06, 2010, The New York Times (online), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/07/opinion/07kristof.html ↵

- Aryn Baker, “Survivors of Wartime Rape Are Refusing to Be Silenced,” March 21, 2016, Time Magazine (website), https://time.com/war-and-rape/?xid=homepage ↵

- Michelle Lent Hirsch and Lauren Wolfe, “Conflict Profile: Democratic Republic of Cong,” February 08, 2012, Women Media Center WMC (website), http://www.womensmediacenter.com/women-under-siege/conflicts/democratic-republicof-congo#reasons ↵

- Office of Special Representative of the Secretary- General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, “Democratic Republic of Congo”, March 29, 2019, United Nations, https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/countries/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/. ↵

- Lyneoyugi, “How Militia Rape me and Tore me Apart,” Lyneoyugi (blog), March 25, 2013, Lyneoyugi, https://lyneoyugi.wordpress.com/2013/03/25/how-militia-raped-and-tore-me-apart/ ↵

- Panzi Foundation, “Panzi Hospital: Panzi Today,” Panzi Hospital and Foundation (website), https://www.panzifoundation.org/panzi-hospital ↵

- Nicholas Kristof, “The world Capital of Killing,” February 06, 2010, The New York Times (online), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/07/opinion/07kristof.html ↵

- Jane Mukuninwa, “Congo Rising: Why am I Rising for Justice,” One Billion Rising (blog), January 17, 2014, https://www.onebillionrising.org/4467/rising-justice-jane-mukuninwa/. ↵

- Jeanne Mukuninwa, “Congo Rising: Why am I Rising for Justice,” One Billion Rising (blog), January 17, 2014, https://www.onebillionrising.org/4467/rising-justice-jane-mukuninwa/. ↵

- Jeanne Mukuninwa: Netlfix Documentary, “City of Joy”, November 11, 2016, https://www.netflix.com/uses/title/80203094 ↵

- “City of Joy,” Last Modified 2019, City of Joy (website), https://www.cityofjoycongo.org/splash/ ↵

- Aida Rocci, “Jane Mukuninwa Interviewed by Art at Harvard University,” December 2015, The City of Joy (website), https://cityofjoycongo.org/jane-mukuninwa-interviewed-by-art/ ↵

- Aida Rocci, “Jane Mukuninwa Interviewed by Art at Harvard University”, December 2015, The City of Joy (website), https://cityofjoycongo.org/jane-mukuninwa-interviewed-by-art/ ↵

- City of Joy, Last Modified 2019, https://www.cityofjoycongo.org/splash/ ↵

- City of Joy, “Program Philosophy: What Make it Different,” The City of Joy (website), Last Modified 2019, https://cityofjoycongo.org/about-city-of-joy/program-philosophy-makes-different/ ↵

- City of Joy, Last Modified 2019, https://www.cityofjoycongo.org/splash/ ↵

- City of Joy, Last Modified 2019, https://www.cityofjoycongo.org/splash/ ↵

- Aida Rocci, “Jane Mukuninwa Interviewed by Art at Harvard University,” December 2015, The City of Joy (website), https://cityofjoycongo.org/jane-mukuninwa-interviewed-by-art/ ↵

- Jane Mukuninwa, “Congo Rising: Why am I Rising for Justice,” One Billion Rising (blog), January 17, 2014, https://www.onebillionrising.org/4467/rising-justice-jane-mukuninwa/. ↵

- Aida Rocci, “Jane Mukuninwa Interviewed by Art at Harvard University,”, December 2015, The City of Joy (website), https://cityofjoycongo.org/jane-mukuninwa-interviewed-by-art/ ↵

58 comments

Julia Edwin-Jeyakumar

This was a well-written article. However even though it was really well written, it was hard to read. I’m Indian and there are people like this who just want to exert power. It is really sad to hear about these instances and hear about pure people and kids being taken away to a path that shouldn’t be on them. It is sad that our literature doesn’t mention these moments, and others just like these. I believe that people should be aware of.

Paul Garza

Amazing article about something that not many were aware of. kind of horrible that I’ve never heard of this situation in any type of class or article. It is scary to know that so many women were put through this. The story of Jane Mukuninwa is one of how she was able to overcome all these issues and become successful. I like that the article ends in a more light-hearted way instead of a dark place.

Abigale Carney

I really learned a lot from this article. I feel like the author explained many of the current issues that are not fully understood by many today. This article makes me want to find more ways to help these women and girls who suffer and survive this abuse. I appreciate you ending your article on a happier note because it encourages us to do more to help these women reach a point of healing and recovery as soon as possible.

Diamond Estrada

Wilzave!

Your article came out so great. I can’t believe how much women have had to suffer in the Democratic republic of Congo, it is sad to know that some people are living in such conditions. Jeans story is unfortunately a very sad one that needs to be told in order to spread awareness about such things happening in other countries. City of Joy is a result of that awareness in creating a change where we see fit. I’m so glad that now women have a place like this where they could go and feel safe and empowered at the same time.

Emmanuel Ewuzie

This was a well done article. It had a sweet ending. These atrocities are horrific and debilitating societies worldwide not only in the Congo. The mass rape reminded me of an event I learned about in my 10th grade World History class. The Rape of Nanking is reminiscent of these events as Japanese soldiers did the unimaginable in Nanking, China.

Dr Celine

What an amazing article you managed to write about one of the many issues that tugs at our hearts. You seemed to have found a perfect balance in describing enough details to fully understand the extent of the physical and sexual torture Jeanne survived but at the same time not make it so detailed that one would start feeling overwhelmed. The story arc ends in a place of joy and healing which does make the piece even more compelling. However, for the ten of thousands of women and girls sexually assaulted, only over a 1000 have found this heaven. This reminds us there is so much we can and should do to continue to protect and help heal the many survivors of violence. Outstanding job! As a Professor, I study and teach about African culture and politics and I realize few people understand the complexities of conflicts and the roots of violence. In this article, you integrated just enough details to remind us of the many complex levels of connections and implications. Bravo!

Raul Vallejo

Overcoming adversity and being independent when she needed to be the most seems to be traits that Jane Mukuninwa demonstrated. It is great that she was able to be as successful as she was, especially when she started off with pretty much nothing in such a war torn land. Great article to read!

Amanda Quiroz

Great article! I honestly, have not heard of the African World War so this article was a very interesting read for me. Jeanne is such a strong woman to have gone through so much and have lost her parents in the civil war. I can not imagine having my parent disappeared and having to face sexual violence on top of that.

Doan Mai

I really appreciate that you write an article about sexual violence. Even though it is hard to read this paper since the topic is so dark, it is still important to let the world know what women have to endure during the African World War. This issue also applied to women throughout the world since numerous raping cases happened during the Korean War, the Viet Nam War, and was considered as casualties of wars. Sexual violence is indeed the most potent weapon as it leaves the long-term effect on the victims’ lives.

Isabella Torres

Topics like these are very important to write about. Although they might be difficult to read because of the intense content, it is necessary to spread the word of what has happened in order to prevent it in the future. There aren’t words to describe how cruel it is for people to commit acts like these, and it is amazing how so many of these women have been able to come back and recover. Before reading this article, I wasn’t familiar with the second Congo war. This is a great article and it did a great job at conveying the subject.