Alexander the Great was known to be stubborn and very persistent. After all, you don’t get to be “great” by giving up easily. Following a victorious battle over a Persian army led by King Darius, Alexander was determined to defeat their navy next. He wanted to cut off their access to the Mediterranean Sea to stop their trading and ensure that they couldn’t get stronger. This was an important step if he wanted to take over Persia. Tyre was an incredibly affluent and powerful port city, which is why it was important for Alexander to conquer.1 However, Tyre’s strength proved to be a challenge. There was a history of failed attacks against Tyre, but that didn’t stop Alexander the Great. He made it his mission to crush this formidable city even though he had no ships himself. The lengths he was willing to go through show just how “great” he was. This battle against Tyre forever changed the course of history, and even a little geography.

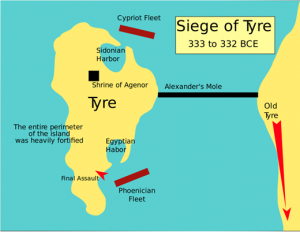

To begin his siege, Alexander first had to go through Byblos and Sidon before reaching the tall and mighty Tyre. He took over Byblos and Sidon easily, as they surrendered right away and would listen to Alexander’s command. This is because they did not have the means to defeat his army.2 The city of Tyre had two territories to its name, one on the shore called Old Tyre, and the other an island located in the Mediterranean Sea called New Tyre. The people of Tyre heard that Alexander was coming their way, and they decided neutrality was their safest option. If King Darius could defeat Alexander the Great, they would be rewarded for remaining loyal to Persia. They believed Persia’s navy and growing army could stop the Macedonians.3 If Alexander the Great took over Persia, their navy was strong enough to stop him from invading New Tyre. Therefore, they gave Alexander a gold crown and other valuable items to show him that they were not a threat to him. Alexander thought this meant they would surrender like the other cities before. However, when he asked to make an offering in one of their temples, New Tyre said they would not let any Persians or Macedonians inside their walls in order to remain neutral. When this news got back to Alexander, he was enraged.4 He gathered all of his men and gave a speech to explain why they needed Tyre on their side. Alexander’s biggest concern was that Persia could go through Tyre and attack his army from behind while he travelled to Egypt. He inspired his men and made them all ready to besiege Tyre.5

He started by taking over the mainland, Old Tyre, without any difficulty. The next step was to defeat the island New Tyre, which was known to have one of the best navies in the world. Alexander knew he couldn’t defeat them without a fleet, so he came up with a plan to connect the island and the mainland, so he could use his army. New Tyre was separated by a channel about 18 feet deep and half a mile wide.6 Alexander planned to build a mole using wood and old stones cemented together by mud. The Macedonians worked efficiently under the direction and praise of Alexander, and they made rapid progress. When he got to the width he wanted, he built two 50-foot towers on the mole. These towers were made out of skin and prepared hides that made them hard to catch on fire, and they protected the workers from getting shot by arrows.

They also would reign down arrows on the Tyrian ships making it hard to reach the mole and fight back. The Tyrians were caught off guard by this, but they had a plan to bring down those towers. Their idea was to put dry sticks and other very flammable objects on a ship, light it on fire, and push it towards the mole. They attached long wooden arms to the mast, so there would be a great reach for the flame to go. They waited for the wind to push the ship in the direction of the mole so it could sail towards it. Two men rode on the ship and lit it on fire just before diving away into the sea for safety. The fire grew rapidly, even too fast for Alexander’s men to put out.7 Alexander lost many men because of this and all the machinery that was on the mole. This made Alexander realize that Tyre couldn’t be taken by the mainland alone. Any man in this situation would think that Alexander should have just taken the treaty, abandoned the siege, and headed to Egypt. However, he was no mere man; he was Alexander the Great, and he was more determined than ever. He longed to humble Tyre and show that they could be defeated. The less likely victory seemed achievable the more Alexander forced it to happen; he was going to end up on top.8

King Darius sent ambassadors to reason with Alexander; they offered money, possession of territories along the Euphrates River, and his daughter’s hand in marriage. Alexander met with his council and discussed the offer from King Darius. One of Alexander’s generals, Parmenion, said that if he were Alexander, he would take the offer and retire from the brutality of war. Alexander agreed that if he was Parmenion he would take the safe way out, but he chose a different option. Instead, he wrote back to King Darius that he would not do him the favor of giving up so easily. Alexander did not need the money and could conquer the whole territory rather than settling for a portion. He also wrote that if he wanted to marry King Darius’ daughter, he wouldn’t need permission from him.9

Alexander knew that he couldn’t siege Tyre only on foot, so he left for Sidon to gain naval power. There he received 80 Sidonian triremes and 120 ships from the people of Cyprus who also feared Alexander’s strength and wanted his pardon for supporting Persia.10 By the end of his journey, he had gained 250 ships, given to him by allies. While Alexander’s fleet was forming, his mole was being reconstructed and machines were being built. He also received 4,000 Greeks hired for him by a recruiter. Alexander wanted to defeat Tyre’s fleet first and then surround the city forcing it to surrender.11

After seeing Tyrians ruthlessly killing and throwing Macedonians corpses into the sea, Alexander’s army became thirsty for revenge. Alexander had two fleets to attack Tyre from both harbors, the Cypriots to the North and the Phoenicians to the South. Tyrians attempted to block the ships from getting close to their walls by placing rocks in the way. While the Macedonians were trying to move the rocks, Tyrians cut their anchors, sending their ships adrift. Alexander combatted this by using chains instead of cables to prevent them from being cut. However, Tyrians had been observing Cyprus ships and knew when their ships were going to be unguarded. While the crew was getting nourishment, Tyrians took this opportunity to sink enemy ships, and chase the others to shore where they were cut down. When Alexander returned, he noticed what was happening and ordered some Phoenician ships to remain in the south to block the harbor while the other ships moved to the north end of the island to commence a counterattack. Although the Tyrians were warned, it was too late. Alexander was already there before they could escape. This led Tyre to lose ships and their control of the sea as their ships were trapped in their own harbor. This allowed the Macedonians to clear the stones and reach the walls of Tyre; but penetrating it wouldn’t be easy. After a lot of work, they ended up piercing the south side wall, but a storm forced them to retreat due to the high waves and flooding. That gave time for Tyre to repair the cracked wall. A couple days later, the weather conditions were much more suitable for another attempt. So, Alexander stationed ships all around Tyre to overwhelm their defenses. The part of the wall that Alexander was planning to take down finally fell and the shield bearers front lined into Tyre. The army took over both towers and climbed the citadel to invade the city. At the same time, both harbors were breached. Tyre was being attacked on all sides with nowhere for them to go. Eight-thousand Tyrians died and thirty-thousand were sold into slavery.12

It is said that Alexander celebrated by giving an offering in the temple that he was denied from accessing in the beginning. He even displayed the machine that broke through Tyre’s wall in the temple just to show them. Alexander the Great brought down the walls of Tyre. The ones that were said to be impenetrable, were taken out in only a year’s time. Countries feared the overwhelming strength coming from the Macedonian warlord. He spent a little time in Tyre before leaving to conquer the rest of Persia.13 To this day, modern Tyre is now a peninsula because of the mole he built back then.

- Jehan Wauquelin, “The Siege of Tyre,” in The Medieval Romance of Alexander: The Deeds and Conquests of Alexander the Great, ed. Nigel Bryant (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2012), 57. ↵

- E.J. Chinnock, The Anabasis of Alexander or, The History of the Wars and Conquests of Alexander the Great (London: The Selwood Printing Works, 1884), 115, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/46976/46976-h/46976-h.htm#Page_115. ↵

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History: Volume V, Loeb Classical Library ed. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950), 464. ↵

- Jehan Wauquelin, “The Siege of Tyre,” in The Medieval Romance of Alexander: The Deeds and Conquests of Alexander the Great, ed. Nigel Bryant (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2012), 57-62. ↵

- Flora Kimmich, G. W. Bowersock, and A. B. Bosworth, “Johann Gustav Droysen: History of Alexander the Great,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 102, no. 3 (2012): 169. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24395532?seq=27#metadata_info_tab_contents. ↵

- Flora Kimmich, G. W. Bowersock, and A. B. Bosworth, “Johann Gustav Droysen: History of Alexander the Great,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 102, no. 3 (2012): 170. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24395532?seq=27#metadata_info_tab_contents. ↵

- E.J. Chinnock, The Anabasis of Alexander or, The History of the Wars and Conquests of Alexander the Great (London: The Selwood Printing Works, 1884), 123, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/46976/46976-h/46976-h.htm#Page_123. ↵

- Flora Kimmich, G. W. Bowersock, and A. B. Bosworth, “Johann Gustav Droysen: History of Alexander the Great,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 102, no. 3 (2012): 171, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24395532?seq=27#metadata_info_tab_contents. ↵

- Flora Kimmich, G. W. Bowersock, and A. B. Bosworth, “Johann Gustav Droysen: History of Alexander the Great,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 102, no. 3 (2012): 171. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24395532?seq=27#metadata_info_tab_contents. ↵

- E.J. Chinnock, The Anabasis of Alexander or, The History of the Wars and Conquests of Alexander the Great (London: The Selwood Printing Works, 1884), 125, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/46976/46976-h/46976-h.htm#Page_125. ↵

- Flora Kimmich, G. W. Bowersock, and A. B. Bosworth, “Johann Gustav Droysen: History of Alexander the Great,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 102, no. 3 (2012): 172. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24395532?seq=27#metadata_info_tab_contents. ↵

- Flora Kimmich, G. W. Bowersock, and A. B. Bosworth, “Johann Gustav Droysen: History of Alexander the Great,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 102, no. 3 (2012): 173-176. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24395532?seq=27#metadata_info_tab_contents. ↵

- Flora Kimmich, G. W. Bowersock, and A. B. Bosworth, “Johann Gustav Droysen: History of Alexander the Great,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 102, no. 3 (2012): 177-178, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24395532?seq=27#metadata_info_tab_contents. ↵

2 comments

cici

Whoa that’s cool he changed geography? That is one persistent dude.

Lisa Zemanski

Very well written and what an amazing history lesson. It kept my attention!! Great Job