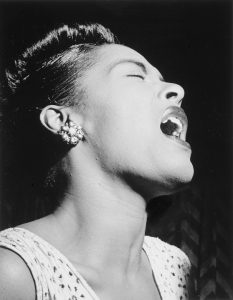

It is yet another lively evening in the 1939 New York club scene. Within Cafe Society, the only integrated nightclub in Manhattan, live music and vibrant chatter are expected normalcy. This January night, however, the gayety was interrupted by sudden darkness and silence. All lights within the club vanished as one struck the stage exposing Billie Holiday, who had just finished yet another splendid performance. Her next song, however, mandated absolute attention. The atmosphere weighed heavy with a discomfiting stillness as servers stood motionless and the audience was left in perplexed paralyzation.1

Piano keys broke the silence, and Billie’s voice, raw and sporadic, grasped the attention of the audience members, whose discomfort had only just begun. Although Holiday’s voice had its way of tugging at the ears of her listeners, the lyrics had contested their souls. These lyrics were unlike any that they were likely to have heard. They articulated a story familiar to some and foreign to others. The piece eradicated the distance between its listeners and the tragic deaths at the hands of racism. “Strange Fruit” tensed the muscles and welled tears behind the eyes of each listener, as the verses unfolded the graphic sorrows of the lynchings within the United States.2

Within the year 1939, the same year that “Strange Fruit” made its appearance, campaigning for antilynching policies emerged. Lynchings had increased rampantly in the years following the Civil War. White mobs would assemble and murder black men and, at times, women with inconceivable barbarity, “often in a carnival-like atmosphere.”3 It is reported that approximately 3,436 lynchings transpired between the years 1882 and 1950. The song “Strange Fruit” illustrated in detail the horrendous nature of these murders with one event in particular.4

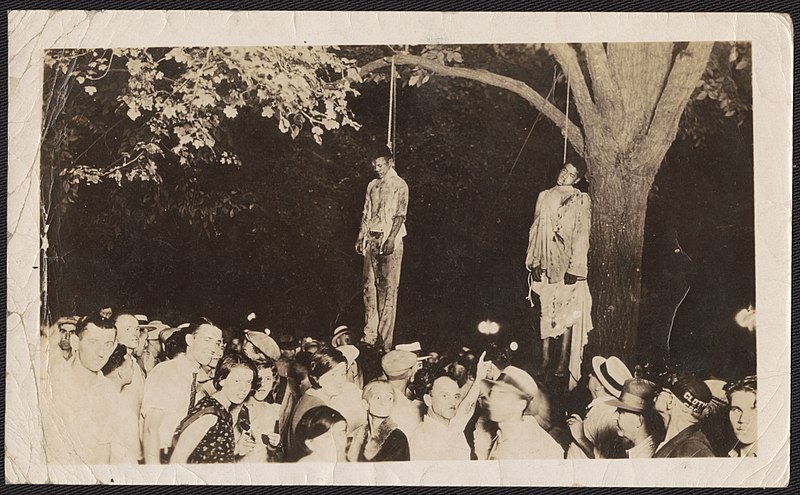

In Marion, Indiana, Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith were severely beaten and lynched on August 7, 1930. A photograph exhibiting this tragedy circulated rapidly throughout the United States.5 The disturbing image made its way to Abel Meeropol, a teacher and writer based in New York. He was haunted by the scene of the torn and bloody spectacles hanging from a tree. Beneath these souls were the unapologetic white men and women, proud of their accomplished work. Days thereafter, Meeropol composed a poem expressing the atrocity that he had glimpsed in this photo, titled, “Bitter Fruit:”6

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,/Blood on the leaves, and blood at the root,/Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze,/Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South,/The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,/ Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh,/And the sudden smell of burning flesh!

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,/For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck/For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop,/Here is a strange and bitter crop.7

“Bitter Fruit” was published under Meeropol’s pseudonym “Lewis Allen,” as he was a closeted Communist.8 The New York teacher was the first to publicize the poem in 1937, and in the two years following, it debuted in the New Masses, a magazine associated with the American Communist Party.9 Meeropol eventually arranged the poem to music, as he did with most of his poetry. Though his wife was first to begin singing “Strange Fruit,” Meeropol began to search for an artist who could reach masses of listeners.10

As Abel Meeropol set out looking for this someone, he was led to Cafe Society, where Holiday made her most frequent earlier appearances. He ushered her towards the piano and played the song for her. According to Meeropol, after delivering this grave ballad, her response was simply, “What does ‘pastoral’ mean?”11 This response of indifference was similar to that of the owner of Cafe Society, Barney Josephson, to whom Holiday said, “You wants me to sing it, I sings it.”12

Similar to Holiday’s reception of the song, the first audiences did not know how to react to the graphic message of this song either. After pouring herself into the song’s premiere at Cafe Society that January night in 1939, the room was flooded with a stale silence. Holiday reported, “there wasn’t even a patter of applause when I finished. Then a lone person began to clap nervously. Then suddenly everyone was clapping.”13 It soon became a routine piece concluding Holiday’s performances. Josephson, owner of Cafe Society, strictly directed the performance, instructing all waiters, cashiers, bartenders, and busboys to remain completely stationary during its performance. The room would dim, and Holiday would release the cries of the lynchings, and immediately she would exit the stage once she had finished.14 And although Holiday appeared apathetic when first introduced to the song, her performances of it conveyed otherwise. Her use of diction and consistent vibrato paired powerfully with her rich and distinctive voice. It was a mixture assorted to narrate an emphatic story portraying the traumas that Black Americans faced.15

The song’s popularity expanded as it became a vessel offering a voice to a social danger that African-Americans were forced to suffer silently. Not only did the song serve its purpose of speaking for the Black community, but it also brought lynching to the attention of the whites they were surrounded with. “It implicated its audience in a shared guilt for the violence done to black men and women,” explains John Carvalho, a music philosopher and author.16 Billie Holiday and “Strange Fruit” became significant instruments magnifying the atrocities targeting African-Americans. The song intended to reach anyone who would listen and prompt them to examine the society they took part of. “‘Strange Fruit’ was an unforgiving and uncompromising look at lynching, the crop harvested by a segregated society that encouraged racial violence,” commented Paul Gelpi, Jr., a journalist writing of a murder case and trial in Louisiana, which proved a suspected black man innocent. W. C. Williams escaped the death penalty with his innocence, but was lynched by a white mob shortly after he was released.17

As the song increased in fame, Billie Holiday sought to have it recorded, to disperse the message farther than she could simply from appearances in nightclubs. However, the song had a concerning backlash that often targeted Holiday herself. Her contracted recording label, Columbia Records, declined the production of the gruesome verses as it became increasingly controversial. Keeping “Strange Fruit” as her finale, audience members had been known to act out with hostility. Many walked out of the performance, some had screamed or muttered slurs while she sang, and others waited until she left the stage to confront her. A white woman had once followed Holiday into the restroom, tearing Billie’s dress, claiming her song had ruined her “night of fun.”18 When traveling the country, she at times had to stop her performance and leave town because of the enraged backlash. Perhaps just as detrimental as those who voiced their disdain for the song were the white men and women who had accepted its message half-heartedly. One of the intended demographics were the white people who had distanced themselves from the lynchings that endangered Black Americans. Regardless, “‘Strange Fruit became a means for white people to use a black woman’s body to absolve their guilt for ‘civilizing’ crimes of racism…” as Carvalho explained.19 Rather than participate in the movement to construct policies criminalizing lynching, most white audiences felt they had serviced their Black neighbors by listening to their take on the traumas they endure.

Billie Holiday finally recorded “Strange Fruit” under Commodore Records, although they doubted that it was significant enough to stand alone. Commodore hired a well-known band to play along with Holiday while also producing another song on Side B of the record. “Strange Fruit” and “Fine and Mellow” became hits and the records sold rapidly. However, Holiday began to perform the song less and less throughout the 1940s as the abuse she weighed from the audience’s disapproval along with her personal life became too heavy to bear. Billie Holiday had a strenuous history of mistreatment from men, and of drug and alcohol abuse. She had been arrested countless times for the possession and use of narcotics, and eventually was “barred” by the New York City police from performing anywhere that alcohol was served.20 The visits and performances at nightclubs, Holiday’s usual scene, would no longer support her. “Strange Fruit” exclusively made appearances when she felt she was struggling to restrain her emotions, and her life bore heavy. It became a separate vessel for Holiday’s sour heartaches channeling hatred and hostility towards her audience through the gruesome lyrics and her violent voice.21

As Billie Holiday’s drug use worsened leading to her death in 1959, “Strange Fruit” persisted to be the anthem of the antilynching movement. It has also become an iconic composition from Holiday’s numerous sensations. Renditions of the song have kept the message alive to the present day. African-American artists such as Josh White, Nina Simone, Abbey Lincoln, and hundreds of others have harbored the ballad through the Civil Rights Movement and many later protests against racism.22 Carvalho adds, “It acquired wider and wider audiences on whom it had the searing effect of imposing silence where there was noise, of reenacting the violence and death that silenced so many voices in the name of preserving a ‘gallant’ way of life.”23 “Strange Fruit” will continue to teach a narrative of the tragic lynching era and the cries of fear, pain, and anguish that African-Americans bore, although no longer silently, in a manner that no textbook ever could.

- John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 113. ↵

- Zoe Trodd, “‘Strange Fruit,’” in Encyclopedia of African American History, ed. Leslie M. Alexander and Walter C. Rucker, vol. 3 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2010), 1036–37. ↵

- David Margolick, “Performance as a Force for Change: The Case of Billie Holiday and ‘Strange Fruit,’” Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature 11, no. 1 (1999): 19, doi:10.2307/27670205. 94. ↵

- David Margolick, “Performance as a Force for Change: The Case of Billie Holiday and ‘Strange Fruit,’” Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature 11, no. 1 (1999): 19, doi:10.2307/27670205. 95. ↵

- Zoe Trodd, “‘Strange Fruit,’” in Encyclopedia of African American History, ed. Leslie M. Alexander and Walter C. Rucker, vol. 3 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2010), 1036–37. ↵

- John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 111. ↵

- David Margolick, “Performance as a Force for Change: The Case of Billie Holiday and ‘Strange Fruit,’” Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature 11, no. 1 (1999): 19, doi:10.2307/27670205. 95 ↵

- David Margolick, “Performance as a Force for Change: The Case of Billie Holiday and ‘Strange Fruit,’” Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature 11, no. 1 (1999): 19, doi:10.2307/27670205. 111. ↵

- Zoe Trodd, “‘Strange Fruit,’” in Encyclopedia of African American History, ed. Leslie M. Alexander and Walter C. Rucker, vol. 3 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2010), 1036–37. ↵

- John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 112. ↵

- Zoe Trodd, “‘Strange Fruit,’” in Encyclopedia of African American History, ed. Leslie M. Alexander and Walter C. Rucker, vol. 3 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2010), 1036–37. ↵

- John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 112. ↵

- John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 112. ↵

- John M. Carvalho “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 113. ↵

- John M. Carvalho “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 112. ↵

- John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 113. ↵

- Paul D. Gelpi Jr., “Strange Fruit: Race and Murder in Small Town Louisiana,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 52 (2011): 80. ↵

- John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 115. ↵

- John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 115. ↵

- “Billie Holiday,” in Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed., vol. 7 (Detroit, MI: Gale, 2004), 452–53. ↵

- John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 116. ↵

- Zoe Trodd, “‘Strange Fruit,’” in Encyclopedia of African American History, ed. Leslie M. Alexander and Walter C. Rucker, vol. 3 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2010), 1036–37. ↵

- John M. Carvalho, “‘Strange Fruit’: Music between Violence and Death,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71, no. 1 (2013): 111–19, https://www.jstor.org. 114. ↵

18 comments

Marie Peterson

This article is a great look at the impact of music as a vessel to help protest and speak out about injustice. It shows how important music was in making people understand injustice in a different way. However, how it still did not make as much of a difference as some might think and caused more injustice. Great job on the article!

Joshua Marroquin

Hi Cecilia! First, I want to say that this was an amazing article and very informative. Also, congratulations on the nomination. This piece is amazing, since it describes in such great the detail the impact this one song had on the nation and the people. However, it is outrageous since this beautiful song has such a terrible backstory around it.

Courtney Mcclellan

This is a very well written article. I first heard this song in my sociology class and finding this article was really helpful for me. It helped me understand the sonf more and why it was so impactful at the time. The image is very impactful because it shows the disregard that white people had for what they were doing because of their separation in the image.

Robert Bohm

What a fine article, so well written and insightful! Your ability to evoke both the pain and triumph in Holiday’s singing of “Strange Fruit” shows you have a talent for probing how art, society and mass culture intermix, sometimes generating the most unexpected kinds of power. Anyway, I’ll end now. I just wanted to say: Congratulations, I admire your talent!

Analyssa Garcia

Hi Cecilia,

Congratulations on your nomination! I really liked this reading. I find it really interesting still to this day, that I had not learned about the lynching of Mexican Americans until my second semester of college. I know the era which you talk about is specifically around the lynching of African Americans, but I was reminded of this history for almost all people of color, it truly is sad. The song strange fruit is also very powerful. I think you did an amazing job with this. Congratulations again!

Sophia Phelan

I truly enjoyed your article and its many layers. The intersectionality of race, music, and society’s relationship to the topic is so prominent in this story. This article is sad and real, and I hope everyone takes away the sorrow and pain your story included, but also the importance of using your voice and platform to take a stand.

Grace Malacara

Congratulations on your nomination! It is well-deserved; this piece is really well-written and describes the narrative of a profoundly moving song. The visuals you utilized, while distressing, were powerful and important since this was not a nice or easy subject. You did an excellent job of conveying the story of this song, its significance, and its ramifications for the anti-lynching struggle. Thank you for presenting this story in such a dignified and graceful manner.

Jesslyn Schumann

Hi Cecilia! First off congratulations on the nomination! I had heard of this song prior to the reading because we had studied it in middle school. What I didn’t realize is that this song was a poem prior to it being a song. I also didn’t realize how much of an impact this one song had on the nation. It is a truly beautiful song though it holds a terrible meaning. Good luck with the awards!

Phylisha Liscano

Hello Cecilia, congratulations on the nomination for best in American studies. This was a very interesting and well written article and I enjoyed getting the chance to read. I can tell lots of research was done and you did an excellent job at being very descriptive. A great yet chilling topic. Overall excellent job and great article.

Chris Ricondo

Congratulations on your nomination as well as your well-written article. I knew I had to read an article about this song after learning about it in class. I had no clue how powerful a song might be in anti-lynching campaigns. The poem demonstrated that African Americans will no longer be silent.