In the 1980’s, America was a storm of confusion, grief, and pain for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ) community. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) spread rapidly through the gay community as the decade progressed. A lack of knowledge on the disease and the large number of cases in the gay population factored into the inaccurate name of AIDS as a “gay cancer” or “gay disease.”1 Despite the pain within the community, one man sought to make a statement for the grief of all those affected by AIDS.

America needed a way to collectively recognize and grieve for the epidemic sweeping the nation. Cleve Jones, during a candlelight march in 1985, had a vision of a memorial quilt, which would change the nation’s viewpoint on AIDS. The candlelight vigil was for Harvey Milk, the first elected openly gay official, and the mayor of San Francisco George Mascone, who were both assassinated in November 1978. Jones, a gay activist who had worked with both men, lived in San Francisco during this time.2 Friends and familiar faces from the Castro district, a prominent gay community within San Francisco, slowly disappeared day after day for Jones. He remarked in frustration to a friend, “If this was just a graveyard with a thousand corpses lying in the sun, then people would look at it and they would understand, and if they were human beings they’d have to respond.”3 On the night of the vigil, Jones asked those in attendance to write down the names of those who had died due to AIDS. Names written on poster boards were then posted on the San Francisco Federal Building next to each other in a patchwork fashion with different interpretations of Jones’ instructions. When Jones stood in front of the numerous names, recognizing some and learning others, he was reminded of a patchwork quilt.4

AIDS is a disorder caused by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a RNA retrovirus that inserts itself into the DNA of hosts. HIV invades CD4+ immune cells, referred to as T-helper cells, by binding to the CD4 molecules on the surface of the cell and inserting its genome into the host cell. The virus requires the host cell’s internal mechanisms to reproduce and destroys the cell during this process over a period of time. “Helper” is an apt name for CD4+ cells, as they play an important role in both innate and adaptive immunity by initiating and aiding immune responses, and account for 75% of all T cells in the body. Normal levels of T-helper cells range from 500 to 1,200 cells per microliter. Diagnosis parameters for AIDS includes having less than 200 T-helper cells per microliter in serum. A diagnosis can also be made if a patient has one or more AIDS-defining illnesses. AIDS-defining illnesses are often caused by opportunistic pathogens, microorganisms that typically do not cause disease but can cause disease when immunity is weakened. An example of an AIDS-defining illness is a skin cancer unique to AIDS patients, Kaposi’s sarcoma. The virus does not aim to kill the host because it is dependent on the host to reproduce, but by damaging the immune system, other diseases can kill the host. Most deaths of AIDS patients is due to an AIDS-defining or related illness rather than HIV itself. Due to AIDS being a co-morbidity, the discovery of the virus and its pathogenesis took longer. HIV is transmitted sexually, through blood transfusions, by mothers during birth, and the use of contaminated needles.5

Friends dismissed Jones’ vision of a memorial quilt and his dream to demonstrate it on the National Mall in Washington D.C. during the National March for Lesbians and Gays. It was simply too morbid to display the names of dead friends. He would never be able to find enough support to make a quilt as grand and macabre as he wanted. However, Jones was determined. After carrying the image of the candlelight quilt in his mind for a year and a half, Jones and his friend Joseph Durant made panels for forty men they knew. Ghastly, they made each panel of the quilt 3ft by 6ft, the size of a typical coffin. With enough panels, the quilt would represent a mass grave of those lost to AIDS. The collection of victims would have to catch the attention of the nation. Jones could not show the “pile of rotting corpses,” but he could lay out the panels on the ground and show the space each person would take up if they were still alive. Alas, Jones was having a hard time spreading the word of the quilt to get more panels for display. The forty panel quilt the two men made was displayed on the front window of the San Francisco Neiman Marcus store during a pride march in the summer of 1987 to gain attention. Jones wanted to get eyes on it from across the nation and even displayed the quilt for the Pope when he visited Mission Dolores in San Francisco. Displaying the quilt for the Pope made some within the gay community upset, but Jones saw it as a positive acknowledgement and a breakthrough to communities outside of the Castro district.6 Being all-inclusive was a major goal for the quilt. AIDS does not discriminate between race, sex, class, sexuality, or age. The quilt would not either. It was not a symbol for only queer people by queer people, but a symbol of mourning for all those affected by AIDS. Quilts carry a traditional symbolism in America and helps to bring together different ideals of conservatism and liberalism. The quilt was not sewn with a political statement behind it, but with the collective grief against a disease not yet understood.7

The first report of AIDS in the U.S. was in 1981, the same year President Ronald Reagan took office. Reagan’s era as President of the United States is known for its conservatism and “moral majority.” Revival of religious fundamentalism during the 1980’s added to the flame that AIDS was a “gay disease” and punishment for sin. Political response was local and centered in areas with higher populations of LGBT+ communities, like the Castro district. Ronald Reagan was criticized for his response to the AIDS epidemic, or the lack thereof. The president first mentioned AIDS in 1987, six years after the first case was reported. Six years of little to no federal recognition or funding resulted in misinformation and a lack of understanding of the virus. In 1982, the CDC only had a budget of $1 million for research compared to $7 million for the less prevalent Legionnaire’s disease. Medical researchers from the CDC added to the growing stigma by using the term gay-related immune deficiency (GRID) before coining AIDS in 1982 due to the high incidence of cases among homosexual men. Public opinion followed these cues from the government and medical community as stigma against those with AIDS grew. Misconceptions of transmission resulted in the denial of service to homosexuals and the use of gloves when LGBT leaders were invited to the White House. Those with AIDS were blamed for contracting HIV because the known modes of transmission are the use of shared needles among drug abusers and homosexual sex. The concern of AIDS being a condition which could affect anyone was not in the public’s consciousness until heterosexual celebrities such as basketball player Earvin “Magic” Johnson contracted HIV.8 Those who developed AIDS during this time stayed silent about their diagnosis out of shame. Families would leave the cause of death out of obituaries and explanations. Within the gay community, funerals were frequent, if they were even allowed to attend by the family of the deceased. The grief piled on fast and many felt the time to mourn one friend was too soon overlapped by the grief for another.9

By the mid-1980’s it was becoming clear that AIDS did not only affect gay men. AIDS was a national crisis that would soon touch every house in the U.S and leave no one without grief. Jones wanted to include the whole nation, but his need for panels was unknown. The quilt was started in a small rented store front in the Castro district. How was Jones supposed to reach out to other communities, let alone the entire nation? Volunteer seamstresses and donations of supplies and sewing machines were all Jones had in mid-July and he wanted to have enough panels for an impact by October. How many panels would be enough? Will anyone outside of the Castro district care? The anxiety of the project slowly alleviated as more volunteers stopped at the shop, now dubbed the NAMES Project. The aim for inclusiveness was accomplished as both gay and straight people made panels. Friends and strangers made panels for those they knew and those they didn’t. Parents came with their children to help make panels for strangers in the community. Mothers made heart-breaking panels for their children who were dying. The most tragic panels were those made by individuals diagnosed with AIDS as they tried to complete their own panels before dying. Family members of those who died before finishing their panel would often bring in the incomplete panels or finish it themselves. The growth of the project was bittersweet as with each new panel there was another name recognized, someone who wasn’t able to finish their panel, or a stranger you never got to meet. Cleve Jones traveled across the nation to spread the news of the quilt in gay bars and was even able to earn publications in the New Yorker and People magazines. Jones worried that the statement wouldn’t be clear with the less than hundred quilts that had been made by the end of July. The immense amount of time and effort might be wasted if they could not make their statement: “Hey look at us! Look at who we have lost! Look who you have lost! Who America has lost!” Fortunately, a surprise came to those in the Castro district as an influx of panels appeared from across the nation. The bars Jones had visited, the publications, the word of mouth had worked. Panels were postmarked from Texas, New York, Montana, Virginia, everywhere. The influx of panels were sewn together into 24ft by 24ft quilt and volunteers prepared to display the massive quilt in October.10

Fortunately, the view of HIV and AIDS has changed since Jones made the quilt. It is no longer regarded as a “gay disease” or a punishment to those who contract it. Misinformation about transmission has decreased since education about the virus as a sexually transmitted pathogen was introduced into schools.11 Treatments that manage symptoms and opportunistic infections have effectively reduced the number of deaths attributed AIDS.12 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has also dramatically increased its resources and response for HIV and AIDS research compared to 1982. The CDC now has the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention (DHAP) which distributes reports about current statistics, treatments, demographics, prevention measures, and future actions for HIV/AIDS patients and the nation. Early administration of antiretrovirus medications aid those infected to suppress the effect of the virus, and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), also aids in HIV infection prevention. However, only 57% of those infected are actively being treated and only a fraction have successfully suppressed the virus. As of 2015, approximately 1.2 million Americans have HIV, but there has been a clear decline in HIV diagnosis. Current efforts for prevention include regular testing for those within high risk groups, PrEP, use of condoms, education, and funding for state programs. Diagnosis disparities between sexuality and ethnicity are a current concern as the diagnosis for Hispanic/Latino homosexual men has increased and African-American homosexual men report less active treatment.13

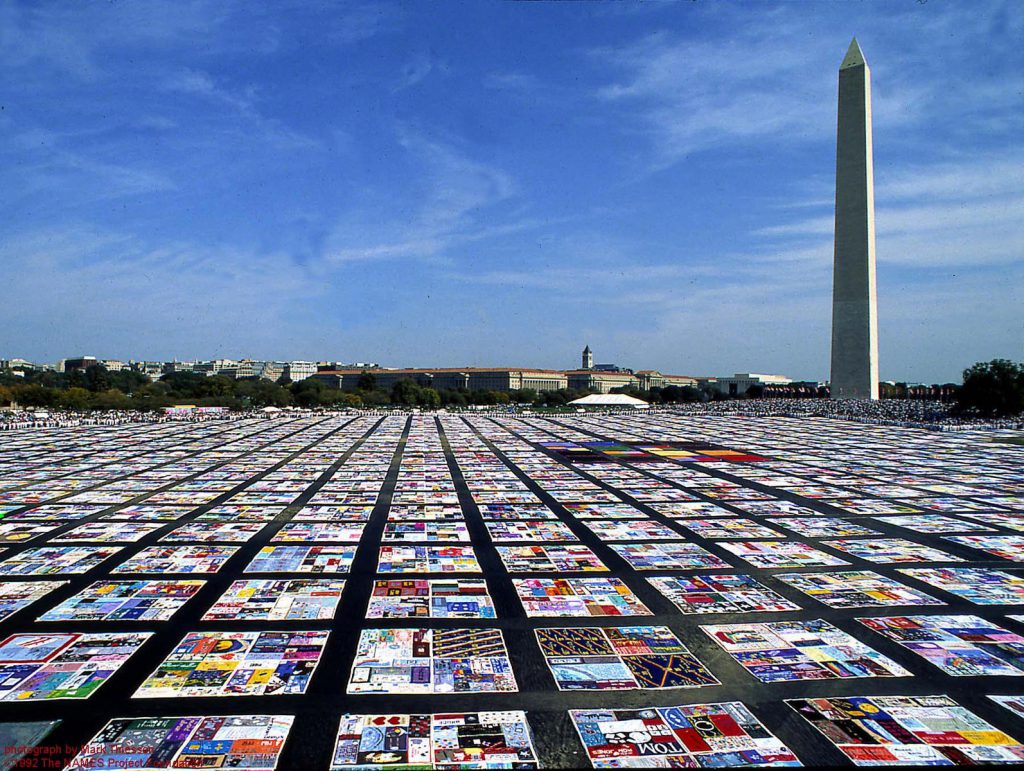

The day had finally come. October 11, 1987 was the first time the memorial quilt was displayed on the National Mall. Jones achieved the dream he had conceived two years earlier. 1,920 panels were displayed on the National Mall during the National March for Lesbian and Gay rights. 1,920 people from across the nation, from all walks of life died from a barely understood disease. 1,920 dead. Tens of thousands grieving them and a nation about to know each name on those 1,920 panels. The quilt was larger than a football field and was displayed on the ground, as Jones always intended.14 Jones spoke at the March about those who he had made panels for. Other speakers for the quilt included Whoopi Goldberg, Lily Tomlin, Harvey Fierstein, and Joseph Papp, who made a panel for his colleague and Tony award-winner choreographer Michael Bennett.15 Panels were decorated with variety and vitality as each represented different individuals. The patchwork demonstrated the widespread effect of AIDS, specific to no one group. Some panels contained narratives of a person’s life, while others were plain with only the name of the deceased. One panel showed the devastation AIDS had on the gay community with twelve candles with only three still burning and a dedication: “to 12 men I expected to grow old with, nine who have passed on and three who will join them soon.”16 The quilt was able to reach the hearts of Americans, those who saw the memorial quilt in person and those who saw it on television.

The workshop of volunteers in San Francisco experienced the profound effect of their hard work through new panels, poems, photographs, and letters. A mother sent a panel for her two sons and expressed her fear for her other gay sons. Another letter included the shame and grief of a woman who had hesitated to hug a dying friend. Other letters were attached to panels explaining that they didn’t personally know the victim of AIDS, but felt sad for those who died that no one acknowledged out of shame or prejudice.17 The quilt represented national mourning and was a surrogate graveyard for those who didn’t get proper funerals. The memorial quilt has been displayed several times since in various places, and returned to the National Mall in 1988, 1989, 1992, and 1996. The Quilt is now kept in the National AIDS Memorial grove. Panels are still being accepted and added to this day. AIDS is still taking lives. The Quilt will remain to celebrate those lost and heal those left behind.18 “The Quilt is the ultimate collage, one that is constantly being reformed, reinvented. Its center is wherever you find it; no one tells the viewer where to start, finish, or pay particular attention. Nor does it require of the viewer anything like an “appropriate” response.”19

- Jason Sheeler, “40 Years of Action and Advocacy The AIDS Quilt Marches Home,” People, April 20, 2020, http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=142644802&site=ehost-live&scope=site. ↵

- Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr, ed., Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Reference, 2007), 60-61. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2660300035/GVRL?u=txshracd2556&sid=GVRL&xid=b38379c5. ↵

- Charles E. Morris III, Remembering the AIDS Quilt (East Lansing, Mich: Michigan State University Press, 2011) xi- xxxiv, http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1035143&site=eds-live&scope=site. ↵

- Christopher Capozzola, Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender History in America, ed. Marc Stein (Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2004), 39-40, Gale eBooks, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3403600022/GVRL?u=txshracd2556&sid=GVRL&xid=89dea767. ↵

- Raymond A. Smith, Encyclopedia of AIDS : A Social, Political, Cultural, and Scientific Record of the HIV Epidemic (Chicago: Routledge, 1998.) http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=8928&site=ehost-live&scope=site. ↵

- Charles E. Morris III, Remembering the AIDS Quilt (East Lansing, Mich: Michigan State University Press, 2011) xi- xxxiv, http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1035143&site=eds-live&scope=site. ↵

- Christopher Capozzola, “A Very American Epidemic: Memory Politics and Identity Politics in the AIDS Memorial Quilt, 1985—1993,” Radical History Review, no. 82 (Winter): 91, http://blume.stmarytx.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=7247238&site=ehost-live&scope=site ↵

- Raymond A. Smith, Encyclopedia of AIDS : A Social, Political, Cultural, and Scientific Record of the HIV Epidemic (Chicago: Routledge, 1998.) http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=8928&site=ehost-live&scope=site. ↵

- Christopher Capozzola, “A Very American Epidemic: Memory Politics and Identity Politics in the AIDS Memorial Quilt, 1985—1993,” Radical History Review, no. 82 (Winter): 91, http://blume.stmarytx.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=7247238&site=ehost-live&scope=site ↵

- Charles E. Morris III, Remembering the AIDS Quilt (East Lansing, Mich: Michigan State University Press, 2011) xi- xxxiv, http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1035143&site=eds-live&scope=site. ↵

- Raymond A. Smith, Encyclopedia of AIDS : A Social, Political, Cultural, and Scientific Record of the HIV Epidemic (Chicago: Routledge, 1998.) http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=8928&site=ehost-live&scope=site. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “HIV/AIDS in the United States,” Atlanta, GA : Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 2008, http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat03837a&AN=SMU.b1481280&site=eds-live&scope=site. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention Annual Report 2015: Putting Prevention Advances to Work” Atlanta, GA : Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015, https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/cdc-hiv-2015-dhap-annual-report.pdf ↵

- Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr, ed., Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Reference, 2007), 60-61. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2660300035/GVRL?u=txshracd2556&sid=GVRL&xid=b38379c5. ↵

- Charles E. Morris III, Remembering the AIDS Quilt (East Lansing, Mich: Michigan State University Press, 2011) xi- xxxiv, http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1035143&site=eds-live&scope=site. ↵

- Peter S. Hawkins, “Naming Names: The Art of Memory and the NAMES Project AIDS Quilt,” Critical Inquiry 19, no. 4 (Summer 1993): 752, doi:10.1086/448696. ↵

- Charles E. Morris III, Remembering the AIDS Quilt (East Lansing, Mich: Michigan State University Press, 2011) xi- xxxiv, http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1035143&site=eds-live&scope=site. ↵

- Christopher Capozzola, Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender History in America, ed. Marc Stein (Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2004), 39-40, Gale eBooks, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3403600022/GVRL?u=txshracd2556&sid=GVRL&xid=89dea767. ↵

- Peter S. Hawkins, “Naming Names: The Art of Memory and the NAMES Project AIDS Quilt,” Critical Inquiry 19, no. 4 (Summer 1993): 752, doi:10.1086/448696. ↵

31 comments

Isabel Soto

To me, this article was fascinating to read it was well structured but before reading this article I had never heard of this memorial so it was so fascinating reading the information. One of the things I found very interesting was the AIDS quilt memorial it was such a beautiful way of honoring the victims of AIDS. Cleve Jones is such an inspiration I give it to him for not giving up and doing everything he could.

Hunter Stiles

First of all, congratulations on bringing awareness to such a serious and brave topic. I find reads like this so beneficial because they really don’t get recognized enough. I thought reading this was fantastic. Reading about this monument introduces me to new knowledge that I can take in because I myself had never heard of it. Speaking about AIDS might be tough for many people, but it has to be spoken in order for people to be more informed about the illness that is claiming the lives of many. The essay not only raises awareness about the AIDS epidemic, but also about the LGBTQ community, which was the target of discrimination because of its growing membership.

Well done.

Faith Chapman

I am a little embarrassed that I have never heard of this AIDS memorial quilt, especially since it seems this event is the reason why I was able to learn about HIV/AIDS as early as middle school. It is a shame that help from the government was provided so late by the Reagan government just because the people who appeared to be at risk didn’t align with the political agenda, but I’m glad that it eventually caved in instead of letting it continue for another 2 years.

Raul Colunga

Great article and educational as well about such a terrible disease. It is terrible that it gained such stigma that lead to so many deaths that could have been avoided. Sadly not only was it a major problem in the U.S., but also in Africa and continues to ravage the continent. Unfortunately there is not enough access to medical facilities to help people recover from this awful disease.

Ashley Perez

Michaela, I really enjoyed reading your article. The writing you displayed was both moving and educational. The LGBTQ community deserves the compassion and acceptance that it is slowly gaining in society. It is projects like these that are the most meaningful, and I am so grateful to have learned about it through this article.

Genesis Vera

This is such an important topic and the way the author presented it was perfect. This could have definitely been a more tear shedding story but I am glad the author ended the story with hope. The information provided was clear and to the point and captured the essence of this significant subject. Ending the article with the memorial picture was a great idea and finished the article properly.

Manuel Rodriguez

Michaela, thank your for sharing your findings with all of us! From what I can see, your informative article about the AIDS quilt is the very first time that many of us are hearing about this spectacular tribute. It brings awareness to not only the seriousness of the disease, but it brings a sense of remembrance to members of the LGBTQ community that lost their lives to discrimination and harsh rhetoric during the epidemic.

Leslie Godinez Parra

Hi Michaela,

very informative and well-written article. Like many others, I had never heard of the AIDS Quilt Memorial and appreciate you bringing awareness to the stigmas that still exist towards minorities such as the LGBTQ+ community. It is so sad to read about what others had to endure as a result of this already debilitating disease. I think it is really something admirable to honor those who have died and rather important to keep pushing forward towards equality.

Chloe Martinez

This article was interesting and successful in informing the audience about the AIDS epidemic in the 1980. It also was saddening to hear about the people who were committed to making the quilts that even people who were dying from AIDS wanted to finish their quilt before passing away. I haven’t heard about the quilt memorial before, so I’m grateful for learning about it now. It makes me reconsider how impactful crafts can be to a society.

Anapatricia Macias

This was a great article! I had never heard of this, and more of us should be aware of it. The AIDS Quilt Memorial is a beautiful way of honoring the victims of AIDS. I am glad that the attitude towards those in the LGBTQ+ community is changing, and that people are starting to value love and what it can bring. Cleve Jones’s commitment is truly inspiring. I admire him for not giving up and doing everything he could so this quilt could receive the attention it deserved.