“Through my presidential faculties, I have decided to take the following actions to accelerate the process of national reconstruction.” This was what all Peruvians heard that April 5 of 1992. That Sunday afternoon, the Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori gave his televised message to the nation to communicate his decision to dissolve the Peruvian Congress, effectively committing a “self-coup d’état.” The reason for this action was that the Congress was not in favor of most of the proposals of the President, and Peru was in the middle of a terrorist crisis. Alberto Fujimori decided that the actions he had to take were needed, and that he needed a legislative power that favored him in his fight to defeat the great menace that was attacking Peru: Shining Path.1

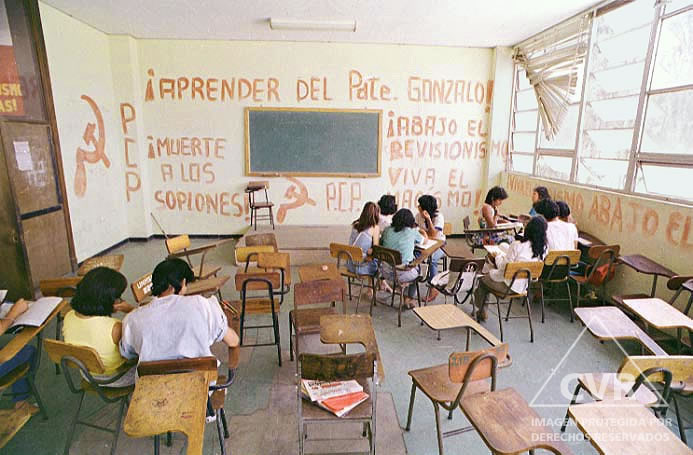

Shining Path, or Sendero Luminoso, was a terrorist organization that committed more than 30,000 homicides between 1980 and 2000 all over Peru. It self-identified as a Marxist-Leninist-Maoist organization, and it also adopted its founder, Abimael Guzman’s, ideology known as “Pensamiento Gonzalo,” or Gonzalo Thinking, a political position that is founded on authoritarianism, far-left ideas, and terrorism as the way to get to power. They did not believe in elections. In fact, their first major attack was the burning of eleven electoral amphorae in Ayacucho on May 17, 1980. Their mission was to indoctrinate rural areas, where they could not be stopped. They taught Marxist, Leninist, Maoist, and Pensamiento Gonzalo doctrines. Because of their Maoist nature, their vision of revolution was based on the peasants being the agents of revolution. Their founder, Abimael Guzman, was precisely that, a teacher in a public university located in the little town of Huamanga. He left this university in the mid 1970s to go underground and be Shining Path’s brain.2

As the years passed, Shining Path went from attacking little towns, forming an army of indoctrinated peasants, to attacking big cities in the late 1980s. Public universities, such as the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, important for being the oldest university in Latin America, were taken already by the indoctrination made by Shining Path, showing that their support in the capital had increased exponentially during those years. This ideological establishment helped them expand from the countryside to the cities.3

The decisions taken by President Fujimori, to advance stronger policies to fight terrorism and to dissolve the Congress, were supported by the general population. The people didn’t like the Congress anymore, due to the poor reputation politicians had, as they always fought for personal or party interests instead of looking for a united national reconstruction. These policies were demonstrated for one of the first times in the executions that took place in the Castro Castro jail. Thirty-five prisoners sentenced for terrorism and treason against the nation refused to be transferred to another jail, provoking a riot but being controlled by the prison forces. Events like these showed to all the population how severely Fujimori was going to fight terrorism in the following months.4

Shining Path did not like the decisions taken by President Fujimori to fight terrorism in a more rigorous way. They came to realize how close their end was. They knew that their time of glory was ending; thus they needed to risk it all. They launched their biggest attack, against the Banco de Crédito del Peru (Credit Bank of Peru) located in Miraflores. What would put them more in the spotlight than attacking a bank in one of the most exclusive residential zones of Peru? This is what they thought, not knowing that this attack would lead to nothing but their downfall. According to the testimony of Juanito Guillermo Orozco Barrientos, also known as “Franco,” Shining Path was to detonate a car bomb in the Miraflores district. Carlos Mora La Madrid and another terrorist identified as “Daniel” refined that target further by suggesting the Banco de Crédito del Peru (Credit Bank of Peru) located in Miraflores. July 16, 1992, was the date chosen to carry out the big attack. This would be Shining Path’s biggest attempt to instill the fear they loved to see on their victims. Tasks were distributed this way: “Nicolas,” “Arturo,” “Manuel,”and “Lucia” (identified as Cecilia Nuñez) were the ones in charge of a prior surveillance in the area to be attacked; “Percy,” “Antenor,” and “Rosa” were the ones who had to go and steal the vehicle that they would use for the attack.5

July 16 came. All the pre-attack tasks were completed by the terrorist comrades; all was ready to start the plan that Thursday morning. The plan started with an attack on four different police stations located in the Villa Maria del Triunfo district, a district located in the same city as Miraflores, but not too near. They also attacked a Banco Latino agency located in La Victoria, being also located in Lima, but not in a near district. Why was this? Why there? What the terrorists wanted was for the police officers to disperse all over Lima looking for them. That way they would have an easier attack. While this was happening, “Carlos,” “Lucia,” “Franco,” and “Antenor” mixed ammonium nitrate with petroleum, producing a lethal explosive that was later packed. Time was passing by and the final hours were closer and closer. At 4pm, a Datsun brand vehicle was conditioned with all the explosive material. This vehicle would transport “Arturo” and “Nicolas,” who were designated to carry a firearm and small explosives to distract the attention of the security personnel. Three hours passed, and at 7pm the second stolen vehicle entered the terrorist property. This vehicle was going to serve as a “security” car for the car bomb, and also as the transportation for the escape of the executors of the attack. “Percy” and “Miguel” were the ones designated to command this escape.6

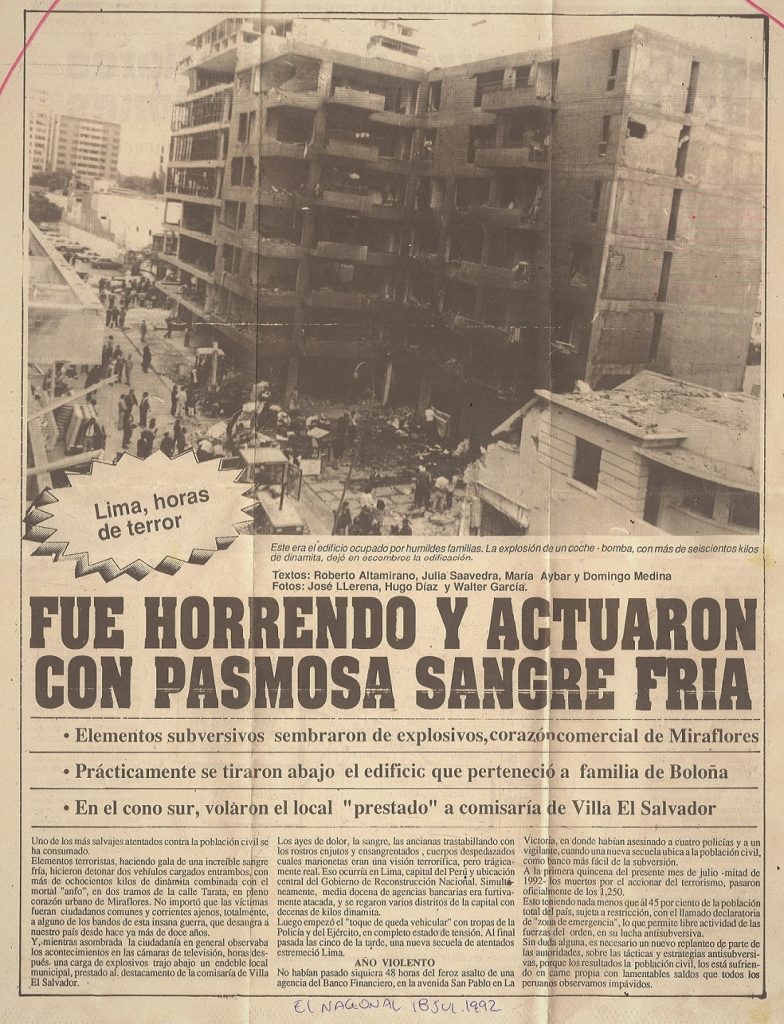

The moment had come; their ghoulish plan was going as designed; there was nothing else to wait for. At around 9pm, both vehicles left the house with one goal: to cause terror. When they arrived at the Banco de Crédito, located on the always-crowded Larco Avenue, the private security of the zone did not let them park on the planned place. They needed to make a quick change. They decided to enter Tarata Street instead. They approached it and when they were close enough, the driver of the vehicle that was charged with explosives slowed down the car, leaving it so it would go by its own to the residential buildings located in that street. At 9:20pm, the “bang” was heard all over Lima, caused by the red Datsun car that contained 400 kilograms of dynamite. Blood was all around, mothers were screaming looking for their sons and daughters, houses were falling apart, damaged by the impact; cars’ sirens that would soon turn into ambulances announcing their arrival to the place. Twenty-five people lost their lives that day because of the fiend attack. Five people disappeared and one-hundred-fifty-five were injured. Osvaldo Cava Arangoitia, who was present at the attack, said that when he tried to escape from his building, on the stairs all he could see was people crying with blood on their ears and nose. A particular victim was a twelve-yea-old little girl who lost her leg because of the expansive wave that the explosion produced. Everything in a 300 meter radius was affected, raising the material losses to US$3.1 million, making this attack one of the biggest attacks in Peruvian history.7

The perpetrators of such a fiendish massacre were not immediately identified; four years of collecting information and investigating had to pass, but even with all this information, the Dirección Nacional Contra el Terrismo (National Direction Against Terrorism) couldn’t capture them. Finally, on June 28, 1996, Juanito Orozco was captured and offered really valuable information regarding the attack. Based on that information, more clues turned up and the murderers were finally captured.8

The international media and support for the victims was quick to arrive. But the main repercussion happened inside the country, especially in some specific socioeconomic sectors of Lima. This was because, before this attack, most of Shining Path’s targets were poor villages from the Andes and from the Peruvian Amazon, but never on an upper-class zone like Tarata Street. This brought about a more severe defense strategy to put a stop to further Shining Path attacks. Even Shining Path itself went into a process of self-examination, because of how big of a mistake for themselves this event was.9

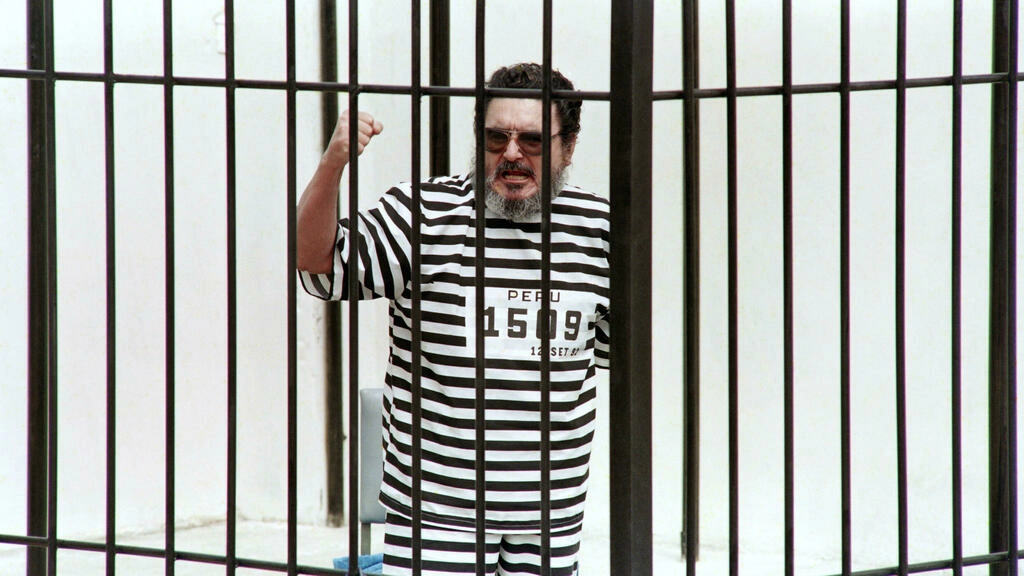

Two days after the attack, the Grupo Colina death squad, composed of members of the Army Intelligence Service and the Army Directorate of Intelligence, broke into the Enrique Guzman y Valle National University, the institution that was famous already for its intense indoctrination and for attracting students into Shining Path. Being inside, the death squad made all the students go outside of their rooms and lie on the floor. Nine of the students were believed to have participated on the Tarata bombing, and they were taken away with the professor Hugo Muñoz Sanchez, who was taken at his house. Nothing was known about them after that day. Three months after the attack, the leader of Shining Path Abimael Guzman was arrested in September 1992, and was sentenced to life imprisonment.10

- Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “La década del noventa y los dos gobiernos de Alberto Fujimori,” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume III, chapter 2.3, (Lima, Peru 2003), 60; Castro, María Fernanda. “¿Qué Sucedió El 5 De Abril De 1992 En El Perú?” El Comercio Perú. Grupo El Comercio, April 6, 2021. https://elcomercio.pe/respuestas/que-sucedio-el-5-de-abril-de-1992-en-el-peru-autogolpe-alberto-fujimori-constitucion-de-1993-revtli-noticia/. ↵

- Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “El Partido Comunista del Perú Sendero Luminoso,” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume II, chapter 1.1: (Lima, Peru 2003), 14, 15, 17; Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “Historias representativas de la violencia,” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume V, chapter 2.1: (Lima, Peru 2003), 45. ↵

- Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “Las organizaciones sociales,” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume III, chapter 3.6, (Lima, Peru 2003), 610. ↵

- Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “La década del noventa y los dos gobiernos de Alberto Fujimori,” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume III, chapter 2.3, (Lima, Peru 2003), 96. ↵

- Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “Los asesinatos y lesiones graves producidos en el atentado de Tarata (1992),” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume III, chapter 2.60, (Lima, Peru 2003), 661. ↵

- Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “Los asesinatos y lesiones graves producidos en el atentado de Tarata (1992),” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume III, chapter 2.60, (Lima, Peru 2003), 661, 662. ↵

- Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “Los asesinatos y lesiones graves producidos en el atentado de Tarata (1992),” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume III, chapter 2.60 (Lima, Peru 2003), 662, 663, 664. ↵

- Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “Los asesinatos y lesiones graves producidos en el atentado de Tarata (1992),” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume III, chapter 2.60, (Lima, Peru 2003), 664. ↵

- Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “Los asesinatos y lesiones graves producidos en el atentado de Tarata (1992),” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume III, chapter 2.60, (Lima, Peru 2003), 667. ↵

- Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “Historias representativas de la violencia,” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume V, chapter 2.19, (Lima, Peru 2003), 627, 628; .Salomón Lerner Febres et al., “El Partido Comunista del Peru Sendero Luminoso,” Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación: Informe de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación Volume II, chapter 1.1, (Lima, Peru 2003), 105. ↵

3 comments

Courtney Mcclellan

Its really sad that the people had no faith in their congress to protect them because of their corruption. Its hard to think that people joined in on this terroristic thinking because they felt left out or unnoticed. Your writing is very well done and your images are very impactful especially the one at the end of the leader in prison.

Javier Oblitas

I personally have a father who had lived in Peru during this time period. Hearing these events regarding the terrorist group in which I had heard so little about from my father have really painted a picture in the scary situation in which he grew up in. I hadn’t known the exact details nor how the terrorist group had formed. This article was very informative and very well written, thank you.

Jerry Rebaza

Te felicito, excelente relato que hace memoria y a la vez homenaje a las víctimas, no solo de Tarata sino también de todo un periodo de horror y que el mundo debe reconocer que ese nunca fue un camino correcto.