Lyceums combined education and oratory, two passions of the mid-nineteenth century, in the 1830’s to create a movement that was both popular and educational. The name lyceum comes from the ancient building in Greece where Aristotle taught. However, in the United States, lyceum did not describe a building, but a revolutionary phenomenon. Josiah Holbrook, the father of the lyceum movement, created this ideology to bring knowledge to adults.1

Holbrook himself gave a series of lectures to an audience of farmers and mechanics in Millbury, Massachusetts, in 1826. He taught instructions in science, politics, art, and literature. From this small project, the lyceum movement quickly spread throughout Massachusetts, New England, and other parts of America.2

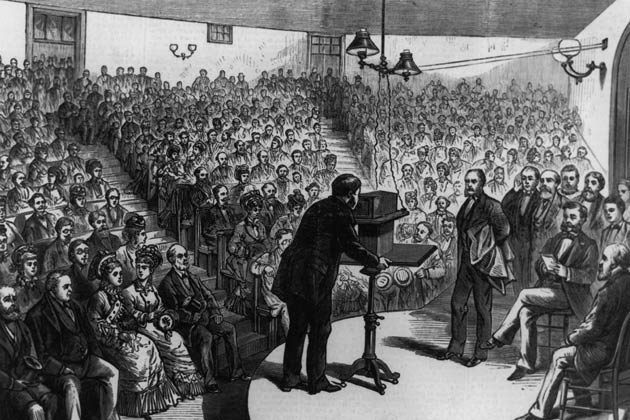

Lyceum organizers used public libraries, vacant schools, and other such spaces for classroom locations. They recruited leading scholars, politicians, and orators of their time to provide entertainment and instructions to adult audiences. Topics such as politics, science, art, literature, history, and philosophy were immensely popular.3

The lyceum in Massachusetts sponsored diverse lectures in 1838 that included “Causes of the American Revolution,” “The Sun,” “The Legal Rights of Women,” and “The Satanic School of Literature and Reform.” The lyceum offered hundred of speeches and featured interesting lecturers such as geologist Benjamin Silliman from Lowell Institute in Boston, naturalist Louis Agassiz, Russian traveler Geroger Kennan, and writer-physician Oliver Wendell Holmes. In 1837 and 1838, approximately thirteen-thousand people attended the Lowell Lectures in Massachusetts.4

The lyceums opened their lectures to everyone. There were only two rules set in place for attending the lectures; first, attire was to be appropriate, and second, no one was allowed to leave the hall during a lecture. While lyceums served as entertainment for adult audiences, their main purpose was to educate.

As the United States became increasingly preoccupied with diverse ideas and battles over slavery, the lyceums served as forums for discussion of public controversies. For instance, in Springfield, Illinois, in 1838, Abraham Lincoln gave a series of speeches to denounce the lynching of slaves in Mississippi and an attack on a free black man in St. Louis. He lectured in lyceums on how the reverence for the laws should be the political religion of the nation.5

In the years following, prominent abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Philips, Frederick Douglass and others became the most popular orators at lyceums. Douglass traveled widely to speak at lyceums. He was featured in lyceums in Central Ohio, the Islands of Nantucket, Massachusetts, and in England. Douglass became one of the most widely admired public figures of his time through his mesmerizing speeches at the lyceums.6

Lyceums were places for men and women to educate and improve themselves by listening to knowledgeable speakers who covered topics in their field. The lectures both reflected and helped strengthen the growing interest in education in the 1800s in America. Lyceums definitely helped the expansion and improvement of the public school system in America. Moreover, they marked the beginning of many decades of efforts to extend the benefits of education to adults. They formed the lecture system of education, which is the staple of university education even today. At the heart, lyceums helped to spread explosive ideas about slavery, freedom, and union.7

- Vyacheslav Khrapak, Reflections on the American Lyceum: The Legacy of Josiah Holbrook and the Transcendental Sessions (Universiy of Oklahoma, 2014), 48. ↵

- Alan Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past Volume 2, 15 edition (New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2014), 138. ↵

- Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past, 138. ↵

- Khrapak, Reflections on the American Lyceum: The Legacy of Josiah Holbrook and the Transcendental Sessions, 52. ↵

- Angela Ray, “Learning leadership: Lincoln at the lyceum,” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 13, (2002): 365. ↵

- Angela Ray, “Frederick Douglass on the Lyceum Circuit: Social Assimilation,” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 5.4 (2002): 625. ↵

- Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past, 138. ↵

31 comments

Luke Lopez

This was a very interesting article on Lyceums. I did not know much about Lyceums before reading this article, but I now know that they were avenues of education. It is also interesting to note that the Lyceums were responsible for the creation of the lecture system in education. Overall, this was a great article that described Lyceums and their impact on the education systems of today.

Honoka Sasahara

Lyceums must have played so important role in the society at that time. I feel that oral messages have bigger power to tell people something than written things have, so it should have a good education for them. Even though there are great schools in this era, it is the wonderful way to go and listen to someone’s lecture for getting knowledge.

Jabnel Ibarra

Lyceum. Something every college student has at one point been a part of but probably never knew it. Reading about what we now know as modern day lecture halls was really interesting as it shows how higher education evolved over the years. I found it entertaining reading about the practices of Lyceums, especially how no one was allowed to leave Lyceum halls mid-lecture and a dress code was strictly enforced, extremely reminiscent of a high school classroom.

Nathan Hartley

I had never heard of a lyceum hall before, but I think they seem very interesting. I think that something like this would be very cool to have in modern times, however I don’t believe that it could be run the same way. I believe that the transferring of ideas is important, however I am surprised that when attending, no one was allowed to leave.

Anna Guaderrama

This is so cool! I love how you chose to write about this because I had no prior knowledge about American Lyceums so to read this article was interesting because I learned something new. I definitely feel like this movement really shows Americans’ thirst for knowledge and that makes me happy because without education we’re doomed to following idiots and repeating history, in general knowledge is important and I feel like you could take something from everything you learn.

Kimberly Simmons

I never knew what lyceums were until reading this article – it’s cool that this was an early version of what we consider to be school today. It’s clear that they held a lot of value, especially considering people went on their own free-will. Aside from that, lyceums had politics, art, literature, and much more included in them that educated adults in the best way possible during this time. Great article!

Maria Callejas

Great article pick, I had no prior knowledge about American Lyceums so this was a complete learning session for me. The Lyceum movement definitely shows the 19th-century Americans’ thirst for knowledge and wisdom.You provide great evidence that highlight the significance of this movement, particularly when you describe how Frederick Douglass was one of the renowned orators.Also, great way to conclude the piece, stating how such events served as inspiration for the college systems today. Good job!

Joshua Breard

I have never heard of Lyceums ever until this article but I found this to be a very interesting article. It was great reading his story about he could make such an impact through his teachings through subjects such as sincere, politics, art, and literature and how it was known across the world. One man can really change the world and it is a goal of mine to be able to be as impactful as this man. Great article!

Teresa Valdez

It is a little strange that people used to attend lectures for fun in their free time. However, I can understand how learning would appeal to Americans during this time, especially as the question of slavery rose as a hot topic. This article does an excellent job at covering different aspects of the lyceums. Not knowing much about the topic, I really like that the article covers information from the origin of lyceums to what they were like at the height of their popularity.

Mario Sosa

This is a nicely well made article! There is always something fascinating to read in these articles. It’s fitting to have lyceums named after the building Aristotle taught in. The lyceums must have been extraordinarily important if it had Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln lecture in them. It is quite intriguing how these lyceums were their own educational organization and not simply a part of a university. Overall, great job.