“In the never-ending project of women’s self-transformation, tattoos are both an end and a beginning, a problem and a solution.”1 From the first tattoo, they have been a way express oneself, whether culturally or religiously or just personally, and they prove that no matter what, you are your own person. In 2012, 23 percent of women in the United States had tattoos, while only 19 percent of men had, which was the first time in known history that more women than men had tattoos.2 Today, we see women everywhere with tattoos and it’s considered a norm, but it hasn’t always been that way. Many women did not start getting tattoos until the 1970’s, at a time when more female artists started to appear along with the rise of feminism. Women started to take control of their own bodies and make their own decisions.

Previous to the 1970s, the majority of women who had tattoos worked in the circus scene. In 1911, the first known female tattoo artist appeared. Maud Wagner was a contortionist in the circus and that was where she met her husband Gus Wagner, known as the “Tattooed Globetrotter.” She demanded that he teach her the art of tattooing, specifically the stick and poke method, and from there she began to tattoo herself and have her husband tattoo her. She became one of the first women to be in the circus with tattoos done by herself. Some sixty years later, women started to enter the field of tattooing.3

One of the first women to start tattooing of her own accord was Vyvyn Lazonga. Vyvyn Lazonga had been an artist since childhood, and in the early 1970s saw a magazine article about a tattooist named Cliff Raven. Raven was currently working in Los Angeles and doing tattoo work with Japanese styles and imagery, one of the first to truly try. Raven’s work inspired Lazonga to try tattooing herself, and in 1972 she moved to Seattle, where the tattoo scene was big.4

In 1972, Vyvyn Lazonga started her first apprenticeship under Danny Danzl, a retired merchant seaman. Lazonga didn’t consider herself a feminist until her apprenticeship with Danzl, due to the clear favoritism of the male artists over her. On most days, Lazonga had to deal with broken tools that she was not allowed to get fixed. She had to fight with Danzl to get him to fix her tools or allow her to fix her own tools. She often dealt with being paid less than her male co-workers. Lazonga had to watch men be promoted, men who had less skill and worked less time than she did. She frequently experienced crude language when dealing with male customers, even though some men were there to be specifically tattooed by a female artist, because they saw it as exciting or exotic. In Margot Mifflin’s Bodies of Subversion, Lazonga describes a specific time when a male customer came in with a group of friends and one friend commented on her sleeves by asking “how would you like to [have sex with] someone like that.”5 Lazonga often dealt with male customers making crude and snide comments about her tattoos.

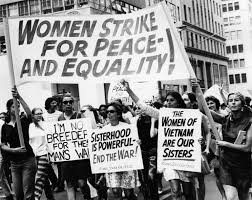

In the 1970’s, women were fighting for their equality in the workplace. In 1963, the Equal Pay Act was passed, which forced employers to no longer be able to discriminate with pay based on ones gender. However, the act did not cover domestics, agricultural workers, executives, administrators, or professionals, which are the fields of employment held by women until an amendment was passed in 1972.6 Now women were able to get jobs with less worry about being rejected because of their gender. Women also started working in the workforce more, because they started putting off making a family, and with Roe v. Wade in 1973, women were able to terminate pregnancies if they weren’t ready for children or were in school or working. Title VII, which made it illegal to discriminate based on sex, was passed in 1964, and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 made it illegal to discriminate on women who were pregnant, which made it just a little easier for women to enter the work place and keep jobs.7

However, women still faced problems. Despite the Equal Pay Act, women still faced a large pay gap. Measured by hourly earnings of year-round workers, the wage gap was in the 35-37 percent range by early 1970s, and then narrowed to 33 percent by 1982.8 Men were being paid for the same jobs but with much higher salaries.

Sexual harassment that women faced in the work place was starting to become a large topic in the feminist community. Two main activist groups were formed: Working Women United in Ithaca, New York, and the Alliance Against Sexual Coercion in Cambridge, Massachusetts, both to fight against sexual harassment in the workplace.9 With groundbreaking court cases like Williams v. Saxbe, which ruled in favor of Ms. Williams who accused her boss of sexually harassing her and then firing her when she denied him, sexual harassment was starting to be addressed in more than just conventions and rallies. The courts recognized the “quid pro quo sexual harassment as a form of sex or gender based discrimination. Quid Pro Quo harassment occurs when an employer requires an employee to submit to unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, or other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature as a condition of employment, either implicitly or explicitly.”10 Courts were starting to recognize the seriousness of the problem being presented.

Mary Jane Haake, who was one of the most influential tattoo artists of the time, was working as a legal secretary when she wandered into Bert Grimm’s shop during her lunch one day, and met Grimm and his wife in 1977. Bert Grimm mentored under tattoo legend Sailor George, and he bragged to have tattooed Pretty Boy Floyd and the US Marshall that captured him, as well as Bonnie and Clyde, and he tried to convince her to come back after work to get her first tattoo.11 Haake, impressed with everything Grimm had said, and having had a previous interest in art, did, and got a poesy.12

Haake then commenced a four-year apprenticeship under Grimm. During her apprenticeship, Grimm taught her how to camouflage scars and recreate hair with fine lines daily. Grimm had learned these techniques from tattooing World War II veterans who were injured in the war, and Haake became interested in the covering of scars. Haake took those lesson and started applying them to redrawing lips lost to cancer, recoloring skin grafts to match the surrounding areas, and disguising surgery scars, specifically after mastectomies.

She soon started receiving referrals from physicians and beauticians, and found herself holding seminars for plastic surgeons and dermatologists.13 In 1981, she opened her own shop where she still currently works, called Dermigraphics. Haake’s skill she learned from Grimm, and her own special touches introduced her to the medical world of cosmetic tattooing, where she primarily focuses today.

Unlike Vyvyn Lazonga, Mary Jane Haake received a college education. During her apprenticeship, she entered Pacific Northwest College of Art and majored in painting and sculpture. Haake did her thesis on tattoos and the human body. In 1982, she got her degree from the Portland Art Museum School and was one of the first people, men or women, to get an official degree in tattooing at any university.14

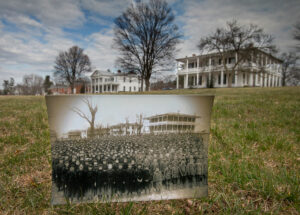

The 1970’s was an explosive period for women to get an education. In 1972, Title IX of the Education Amendments was passed. Title IX prohibited discrimination based on gender in any federally-funded program or activity. With the creation of Title IX, women were able to enter universities without the worry of being denied based on their gender.15 In the 1970s, the Senate passed the Equal Rights Amendment, which proposed banning discrimination based on sex, but it fell short by three votes.16

It was not just in college that women were gaining educational momentum. In 1976, 119 women joined the Corps of Cadets, 62 of those women graduated in 1980. This was the first class of women at the United States Military Academy at West Point. The women still faced setbacks, such as disrespect and embarrassment. Multiple press conferences were held over the course of the women’s enrollment with the purpose of reversing the military’s decision to allow women into the Academy.17 But these opinions only pushed the women to do their best and prove that they should be there.

The 1970’s was a time of change. From the hippie movement to equal rights, people’s views of the world were changing. There were women who took up the fight to fight for equal rights with rallies and protests, then there were women like Lazonga and Haake who just simply did what they wanted, even though it was “forbidden.”

- Margot Mifflin, Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo (Powerhouse Books, 2013), 147. ↵

- Samantha Braverman, “One in Five US Adults Now has a Tattoo,” Harris Interactive, February 23, 2012. ↵

- Karen L. Hudson, Chick Ink: 40 Stories of Tattoos—And the Women Who Wear Them (Polka Dot Press, 2007), 19. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Body Adornment, 2007, s.v. “Encyclopedia of Body Adornment,” by Margo DeMello. ↵

- Margot Mifflin, Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo (Powerhouse Books, 2013), 54-60. ↵

- Christopher B. Snow and Jane K. Snow, “The Equal Pay Act of 1963,” Utah Bar Journal, no. 26, 6 (December 2016): 14-16. ↵

- Samuel Issacharoff and Elyse Rosenblum, “Women and the Workplace: Accommodating the Demands of Pregnancy,” Colombia Law Review 2154, 2221 (1994): 2156-2158. ↵

- Solomon W. Polachek and John Robst, “Trends in the Male-Female Wage Gap: The 1980’s Compared with the 1970’s,” Southern Economic Journal (2001): 869-888. ↵

- Carrie Baker, “The Emergence of Organized Feminist Resistance to Sexual Harassment in the United States in the 1970’s,” Journal of Women’s History 19 No. 3 (2007), 161-184. ↵

- Derek T. Smith, “Landmark Sexual Harassment Cases: Williams v. Saxbe,” Derek Smith Law Group, Attorneys at Law, June 15, 2017. ↵

- C.W. Eldridge, Harriet Cohen, and Eric McKay, “Pretty Boy Floyd,” Tattoo Archive. ↵

- Peter Korn, “Q and A with Mary Jane Haake,” Portland Tribune- News, August 16, 2007. ↵

- Melissa Navas, “Race for the Cure: Routes to reconstruction weave a maze for women,” The Oregonian, September 14, 2010. ↵

- Sophia June, “Portland Is One of the Only Places Where Breast Cancer Patients Can Get Nipple Tattooing, Covered By Insurance,” Willamette Week, July 14, 2017. ↵

- Suzanne Bianchi and Daphne Spain, “Women, work, and family in America,” Population Reference Bureau, no 51, 3 (December 1996). ↵

- Roberta Francis, “History,” ERA: History. Accessed November 28, 2017. ↵

- Kelly Schloesser, “The first women of West Point,” www.army.mil, Oct. 27 2010. ↵

78 comments

Andrew Dominguez

Before this article i never knew there was such a history in tattoos, or girls would have a hard time being an artist.The part i like in this article is the covering of scars with tattoos which especially great sine it helps veterans. What i don’t understand is how she couldn’t get her equipment fixed. Why should they care if she was a girl, they should just worry about getting money.

Alexandra Lopez

Seeing women pass along me in shopping centers covered with tattoos never really made me think twice about it. I know how common tattoos are amongst men and women, but I did not know of the hardships tattoos came with. Reading about what an impact tattoos had on women is astonishing. It’s bizarre how I know women who’s whole body is covered in ink yet I had no idea about this movement. Watching tv shows where the main tattoo artist is a female makes me realize what a long way women have came to amount to within all of the pressure and discrimination. Amazing article.

Miranda Alamilla

It’s so interesting to read about the hardships that females have faced in the past. Being a female working in the 21st century, I know not of all the discriminatory acts against a female in the workplace. I really liked this article because I love tattoos. I feel like they are a form of expression and that males should not be the only ones eligible for tattoos. tattoos will not alter a woman’s ability to work, just like it does not alter a man’s ability to work. I didn’t know that tattoos were only seen in circus’s in earlier times, but I’m very glad that they’re seen now more as artwork because they are. Tattoos are art.

Hanadi Sonouper

The common misconception among tattooed stereotypes are considerably almost always liked to criminals, gangs, or people with bad decisions. However, that is false, tattoos are a statement that we as human beings want to showcase or highlight as something much deeper than ink on our skin. Woman have truly played a great role in this movement, because just as men are able to be dominant roll among every role in life, females have just as much as a say as to what they can do. They have a voice, and I am glad to hear that they joined together for an artistic movement that means so much to them.

Iris Henderson

I loved this article about women and tattoos. When I read about the equal pay act being passed in 1963, which I am already familiar with, it really reminds you how short a time ago that was and how far we still need to go. I think the author had excellent detail on this topic and picked great examples of women in the industry to share. I especially liked the coverage on Mary Jane Haake.

Matthew Wyatt

This article is a compelling reminder that gender discrimination was, and continues to be, pervasive throughout American culture, even in fields that are typically considered more progressive and deviant from the norm. I had never heard of the amazing contributions of these women, and am glad to have learned more about them. I would recommend a quick edit looking at some of the more wordy sentences, but ultimately this is a well written article on an intriguing topic.

Bryan Martin Patino

Growing up a common stereotype for anybody with tattoos was that they where most likely criminals or delinquents. I had once said that i would like a tattoo and my parents freaked out thinking i would grow up to go to jail. this article not only disproves that tattoos automatically make you a criminal it show that its a way for women to them selves as strong independent women. its so amazing seeing that something so simple could lead to two different view to somebody, im glad that there is a positive out come to something that used to be a huge taboo.

Maria Mancha

I consider myself feminist and this story just spoke to me. I don’t have any tattoos but I always wanted one. And this article is convincing me even more especially because I didn’t even know the impact tattoos had on women. Tattoos became its own movement in a sense that being a women doesn’t stop you from doing what you want. You can be anything even a tattoo artist. I enjoyed mostly how she discussed Maud Wagner, Vyvyn Lazonga, and Mary Jane Haake and went deeper into the history about them. Therefore it was a really great article with great information, it was truly inspiring.

Destiny Renteria

I really find this article because I have tattoos myself. It is nice to know where it comes from and how the first women even started tattooing. Just like other articles I have read, very well written, but a little bit too much information, which is what makes it long. Lazonga learned the stick and poke method which is actually known to be harder and I am glad a woman took on that challenge. It is sad to know that many women faced sexual harassment, but this always pushed them to do better and never stopped them from achieving their goals.

Cheyanne Redman

I find this article very interesting, and empowering. You rarely see woman in the spotlight, and seeing these women becoming so successful based off a “mans” work is always something nice to see. I have seen Maud Wagner as an inspirational figure because she set a foot in the door for women in a a very challenging field, this article pinpoints her whole entire story, and where she came from. She is an inspirational figure for all women.