The Battle of Sekigahara took place in Japan near the end of the Sengoku Jidai or The Warring States Period (1467-1615). These nearly 150 years were the most violent times in Japanese history, where warlords battled each other for land and power. Since this period lasted for so long, the way battles were fought had changed. The first battle of the Sengoku Jidai that happened in 1467, called the Onin War, was fought with bows and swords, but by the end of the era, battles were influenced by the introduction of European cannons and guns. The Onin War, which started it all, had lasted for ten years and was instigated by the Hosokawa and Yamana clans. At that time, the capital of Japan was Kyoto, which housed the Ashikaga Shogunate, and it was the Ashikaga that held authority over the country. In the city, both clans owned mansions and their rivalry took a turn for the worse. The two clans fought in the city, and others who were caught in the crossfire had to choose to side with one or the other to protect themselves. Soon the situation spiraled out of control and the shogunate was not able to quell the fighting. The Onin War caused a domino effect that started with the Hosokawa and Yamana clans, and year by year the whole country was at war.1

During the Sengoku Jidai, there were three great unifiers, the first being Oda Nobunaga, who conquered central Japan. He started making waves in 1560, when a powerful warlord attempted to take over Nobunaga’s territory. Severely outnumbered by the invading Imagawa clan, Nobunaga managed to take Imagawa Yoshimoto by surprise under the cover of a thunderstorm and killed him. This victory marked the beginning of Nobunaga’s conquest of central Japan and was now aided by fair weather clans who had supported Imagawa. Eight years later, in 1568, with the help of his ally Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was watching his back, Nobunaga started his march towards Kyoto to remove the shogun and put himself in power. Needless to say, this aggressive move was not well received by the other warlords, who felt threatened by Nobunaga taking control of Kyoto. Doubly so by Ieyasu moving from his castle in Okazaki to another more advantageously positioned Hamamatsu castle in 1570. The location of Hamamatsu castle was at the mouth of the Tenryugawa river, which starts in the territory owned by Nobunaga’s rival Takeda Shingen. The Takeda clan was another prominent force that should not be taken lightly. Takeda Shingen marched in the snow towards Hamamatsu castle and had forced Ieyasu’s forces back behind the walls. After the defeat, Ieyasu’s general Torii Mototada had ordered the gates to be closed. Ieyasu knew that that was what Shingen wanted, so he told Mototada to leave them open and light fires to guide the retreating troops back. Surprised by this, Shingen thought that the gates being left open was a trap, so he decided not to storm the castle and had his troops camp out in the cold. Making use of the terrain, Ieyasu had sent out 16 riflemen and 100 other foot soldiers at night to attack their camp. The Takeda were known for their horsemen, but in this case it was their downfall when the Tokugawa troops led the horsemen down to a ravine. Under the cover of darkness coupled with the snow, many of the horsemen could not stop in time and fell in, while the Tokugawa soldiers finished them off.2

Since Nobunaga’s conquest of Kyoto, things had been going well and he had become the most powerful man in Japan. In the summer of 1582, Nobunaga’s general Toyotomi Hideyoshi fought against the Mori clan on the west side of the country, while Tokugawa Ieyasu was fighting on the east side. Hideyoshi’s battle at Mori’s Takamatsu castle stagnated, and he was unable to break through the Mori defenses. In order to win, he decided to request reinforcements from Nobunaga. What Hideyoshi didn’t know was that his request came with a major consequence. Nobunaga had sent out his troops in advance under the command of another general by the name of Akechi Mitsuhide and he would catch up to them at Takamatsu castle. This had left Nobunaga unguarded, and at night Mitsuhide turned the army around with the intention of betraying Nobunaga. During the attack, Nobunaga was staying at Honnoji temple in Kyoto when Mitsuhide’s troops arrived and set the temple ablaze, knowing that he could not escape, Nobunaga took his own life and died in the fire.3

After the event, Mitsuhide declared himself the Shogun, and after hearing the news, Hideyoshi surrendered his assault and took his troops back to Kyoto. Surprised that Hideyoshi returned so quickly, Mitsuhide was caught off guard and had his troops position themselves on a hill by the Yodo river; but it was for naught. Hideyoshi had routed the enemy who had dispersed in all directions, and Mitsuhide died at the hands of a peasant gang.4 But Hideyoshi’s work was far from over; he could not be the shogun because he was not from a notable family; so he became the civil prime minister. Hideyoshi picked up where Nobunaga left off and became the second great unifier. And by 1591, he had control of the entire country. Seven years later, in 1598, Hideyoshi became ill and his heir was only five years old. Before he died, Hideyoshi held a meeting with five of the strongest warlords and made them swear to rule together along with five commissioners until his son was of age to take his father’s spot. The five warlords were Tokugawa Ieyasu, Maeda Toshiie, Uesugi Kagekatsu, Mori Terumoto, and Ukita Hideie. Hideyoshi had made Toshiie the guardian of his son along with Tokugawa Ieyasu. Then on September 15, 1598, Hideyoshi had succumbed to his illness.5

This was where the scheming and working in the shadows took place, because everyone knew that the country was not going to remain peaceful, now that Hideyoshi was dead. The first to start the scheming was Ishida Mitsunari, who was trying to decrease Tokugawa Ieyasu’s influence. After Ieyasu moved into the late Hideyoshi’s castle, Mitsunari went to Toshiie, who was the guardian of Hideyoshi’s son, to try and turn him against Ieyasu. Luckily for Ieyasu, Hosokawa Tadaoki was there to counteract Mitsunari’s scheming and convinced Toshiie and his son that it would be in his best interest to not mess with Ieyasu. Having his plan backfire, Mitsunari then chose to stage an assassination of Ieyasu, but that too failed when Ieyasu’s generals found out about it. They had decided to kill Mitsunari, and in a surprising turn of events, Mitsunari fled for his life and sought protection from Ieyasu. No one knows why Ieyasu granted Mitsunari protection, but his choice made the future tougher for himself.6

So, who was this Tokugawa Ieyasu? He held territory in the “breadbasket” of Japan, which made him a very wealthy and powerful man. Power was determined by how much food-bearing land someone controlled, and Ieyasu’s territory in the Kanto region provided him with 2.5 million koku. One koku is 180 liters of rice, which is enough to feed a man for one year. Coupled with being rich, Ieyasu had chosen strong allies; he was on Nobunaga’s side, while other clans perished while trying to oppose him; and he was smart enough to back Hideyoshi’s rule. After Maeda Toshiie died, Ieyasu became the guardian of Hideyoshi’s son Hideyori, and he moved into the Osaka castle where Hideyoshi was staying. This angered the commissioners and warlords, including Mitsunari. But during that time Ieyasu also dealt with the troublesome Uesugi clan that was to the east of Japan. Mitsunari saw this opportunity, and himself and a group of others issued a complaint that Ieyasu believed was a declaration of war.7

Since the time of Hideyoshi’s death, everyone was forming alliances, and Ieyasu was no different. A rule that he broke being one of the rulers was that he could not marry off children for diplomatic reasons. But that was one of the ways he had formed alliances that allowed him to form the Eastern Army. The Eastern Army, led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, were the separatists who did not want to wait for Hideyori’s son to rule. When the Eastern Army formed, Mitsunari then formed the Western Army, who were the loyalists. The whole country was now divided by whom they supported. Ieyasu had started the campaign in the east and split his army; he sent his son to attack the Sanda clan, while he led 30,000 men towards the west where Mitsunari was. Getting closer, Ieyasu ordered his subordinates to take Gifu and Kiyosu castles, which were on two important roads, while Mitsunari was taking Fushimi castle, whose defenses were strong and held up his army. After taking Fushimi castle, he moved on to Ogaki castle, where he met with the Eastern Army and had a skirmish in Akasaka. Nothing came out of it, but at night a couple of Mitsunari’s generals had posed a night battle and believed they had the upper hand. Mitsunari’s strategist scoffed at the idea, calling it weak, and Mitsunari called for a retreat to a more strategic location at a village in a valley called Sekigahara.8

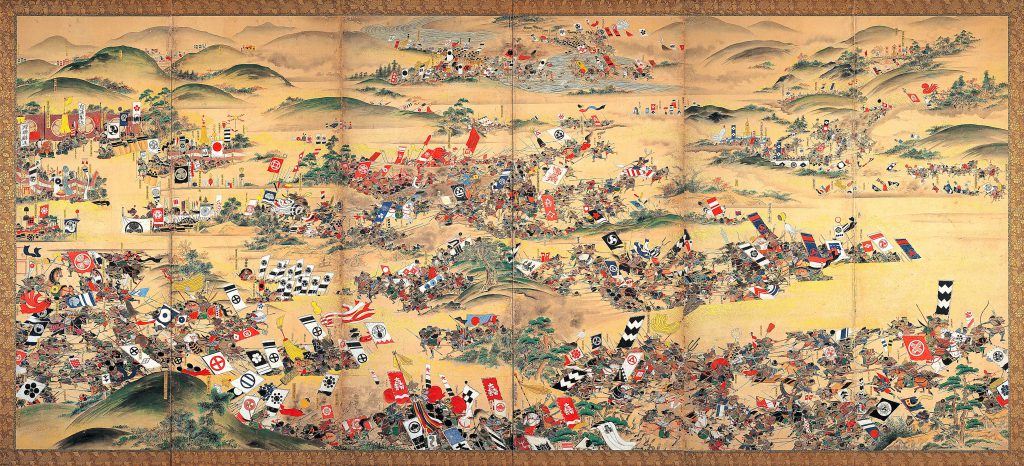

The year was 1600, and both armies had arrived at around 1:00 am, but a torrential rain was coming down and by the time both had set up their positions, it was 4:30 am. Mitsunari’s plan was to draw the Eastern forces into the valley and surround them; two sides of the valley were blocked my mountains, which made running away difficult. The rain had let up and had turned into a dense fog. By 8:00 am, the fog had lifted and both armies were surprised by how close they were to one another. Both armies had around 80,000 troops, and the Eastern Army kicked off the battle with mounted cavalry led by Ii Naomasa and Fukushima Masanori straight to Ukita Hideie’s positon. The push had shocked the Western Army, and 20,000 more Eastern forces charged towards Mitsunari’s encampment. Mitsunari then had cannons fire upon the west to be used as a fear tactic, which succeeded, and forced his enemies back. Two hours had passed and only 35,000 of Mitsunari’s alliance had joined the battle. The Shimazu clan, 3000 in total, had not moved from their position. Angered by this, Mitsunari personally went to their camp and asked them to join the battle. Shimazu did not respond positively, which may have been because his advice about the night attack prior to the battle had been scoffed at.9

Another hour passed and the battle went back and forth with no clear winning side. Mitsunari, looking from a vantage point at Mount Sasao, had called for all of his forces to make a final push. Mitsunari had an ace up his sleeve; 15,000 men led by Kobayakawa Hideaki had been waiting on Mount Matsuo for Mitsunari’s call to charge at the Eastern Army. But before the battle, Hideaki had sent a letter to Ieyasu that told him that he would switch sides to the east. When Mitsunari signaled for Hideaki, he did not respond. At the same time, four other divisions and Kikawa Hiorie were ordered to attack, but they too defied Mitsunari’s orders. Hideaki having been given a push by Ieyasu and charged towards Mitsunari’s forces, and the Shimazu clan then fled from the fight. Overwhelmed, the remaining Western Army had lost and Mitsunari was captured and executed in Kyoto.10 Tokugawa Ieyasu was now the third great unifier, which led the country to 200 years of peace. His descendants had feared that foreign influence would thrust the country back into another age of war, so they turned away all foreigners, with only a few exceptions for trade.11

- Stephen R. Turnbull, War in Japan 1467-1615, Essential Histories 46 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002), 8-14. ↵

- Stephen R. Turnbull, War in Japan 1467-1615 Essential Histories 46 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002), 42-49. ↵

- Stephen R. Turnbull, War in Japan 1467-1615 Essential Histories 46 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002), 52-53. ↵

- Stephen R. Turnbull, War in Japan 1467-1615 Essential Histories 46 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002), 54. ↵

- Anthony J. Bryant, Sekigahara 1600: The Final Struggle for Power, Osprey Military Campaign Series 40 (London: Osprey, 1995), 7-8. ↵

- Anthony J. Bryant, Sekigahara 1600: The Final Struggle for Power Osprey Military Campaign Series 40 (London: Osprey, 1995), 9, 10, 12. ↵

- Anthony J. Bryant, Sekigahara 1600: The Final Struggle for Power Osprey Military Campaign Series 40 (London: Osprey, 1995), 8,12,13,14. ↵

- Anthony J. Bryant, Sekigahara 1600: The Final Struggle for Power Osprey Military Campaign Series 40 (London: Osprey, 1995), 12,13,38,39,41,49. ↵

- Anthony J. Bryant, Sekigahara 1600: The Final Struggle for Power. Osprey Military Campaign Series 40 (London: Osprey, 1995), 25,51-65. ↵

- Anthony J. Bryant, Sekigahara 1600: The Final Struggle for Power Osprey Military Campaign Series 40 (London: Osprey, 1995), 47,66-80. ↵

- Stephen R. Turnbull, War in Japan 1467-1615 Essential Histories 46 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002.), 87. ↵

85 comments

Kristen Leary

This is certainly a time and place in history I do not know much about, but based on your article there appears to be a rich and interesting history to be learned. It is interesting to see how important family ties and alliances were especially in this society and other societies around that time as well. Good job on writing an article with the specificities of what happened historically, at what time, for what battle.

Donald Glasen

This article is a great read to learn more about Japan’s history. This time period is one of the more interesting ones to me I always enjoy learning more new parts of it. I believe that the images within the article like the map help build upon the story. The change within it is most interesting to me and I enjoyed the article overall.

Alejandro Fernandez

This particular article focuses on Japanese history by describing specific events that have contributed to the current state of the country. Through maps and illustrations, the author informs the reader of Tokugawa Ieyasu and how he aimed to unify Japan. Additionally, the reader learned certain Japanese concepts such as the measure of power through land and food, rather than typical physical strength. Through this, one can acknowledge the history of Japan and their continued effort in unification as they continue to thrive in today’s society.

Christopher Morales

This was an interesting article that you made very easy to read. I found that the history described expressed a lot of different ideas how Japan formed and became the way it is today. It showed the change and advancement of how war games changed. The use of images within the article also really intrigued me and brought my attention to how they correlated to the readings. I also found how interesting it was that at the end, foreigners were limited within the country which is something we saw for a long time with them. It was interesting how history is seen throughout the 1900’s.

Peter Alva

I personally knew nothing about Japanese history and still would say I don’t but this gave me great insight into how the politics where in this region. This story timeline of war within Japan Differently interests me to look more into this region being that I know of so many things that are influential from Japan.

Martina Flores Guillen

Reading the article as a whole, what drew my attention within the various eye-catching sections, was the use of images. Implementing a better structure idea of the way each tactic was utilized to seek overall power. One fact that was previously unknown from my perspective was the factors one had to fit under to be perceived as wealthy in Japan, one being “how much food-bearing land someone controlled.”

Sydney Nieto

This article was interesting. There aren’t many stories about wars in Asia, so I was excited to read about this. There was a lot of back and forth, but I found it interesting how Nobunaga became the most powerful after he conquest Kyoto. I also found it interesting how long this war was and how Mitsuhide got the title “shotgun”. Overall, great article.

Noelia Torres Guillen

This article was very informative in presenting history that is not talked about or thought yet is important. I was able to keep up with the characters and what they did who they were, etc. I could imagine the fire, the betrayal, even the 5 year old son. I always was curious about why Japan closed themselves off but now it makes sense. There was war and betrayal for way too long. The constant change in power and battles between clans made it difficult for there to be any sign of peace.

Barbara Ortiz

This was a great article to read after learning about the shogunates in Japan. It is definitely the area and time period of history that I feel I am weakest on knowing anything about. I especially liked the use of the maps and illustrations in your article as it enhanced the story about Tokugawa Ieyasu and how he become one of the great unifiers in Japan’s history.

Melyna Martinez

This article shows an interesting point of view of how power was measured in japan, as it was based on someone’s control of land and food a person had instead of someone’s physical strength. The explanations of the civil war I believe show how the change of power in Japan started, as I was not aware Tokyo was not always the capital. This article showed me that Japan has changed in power the different groups and its enormous effect on the country.