It’s October 2019, and things have taken a turn for the worst. In the High Court of Justice in Northern Ireland, Justice O’Hara oversees the first trial related to paramilitary activities since the Diplock Trials were first introduced in 1973. According to tapes collected as part of an academic history project, then 35-year-old Ivor Bell confessed to the killing of Jean McConville in 1972. Bell, a known veteran of the IRA paramilitary group, had given his testimony in a collection of interviews known as The Belfast Project. In the tapes of these interviews, Bell claims that the killing of McConville was greenlit by the popular Irish politician Gerry Adams. The inclusion of Adams as a key figure had changed the weight of this case. Adams was the president of the Irish Republican party, and has been hailed as the peace-bringing hero who brought an end to thirty years of terror.1 However, Adams was not without his enemies. And a manufactured story about his involvement with a known terrorist organization was not outside the realm of possibilities. Bell, who had become an opponent of Adams’ peace tactics, was now 82 and suffering from dementia, but he also might have, at the time of the interview, lied to try to incriminate his rival.2 Justice O’Hara was caught between a rock and a hard place. At the moment, the issue at hand wasn’t whether Bell had committed the murder; he most certainly had. Rather, it was an issue of whether or not the interviews could be considered reliable testimony. It was no secret that Bell was no fan of Adams, and it wasn’t out of the question for a rival to lie about his adversary. But there were other stories that corroborated Bell’s allegations. If the story this Belfast Project told were true, then it could create outrage among different factions in Northern Ireland. The outrage most certainly could mean a return to the car bombings and kidnappings that took the life of Mrs. McConville’s and thousands of others fifty years ago—A return to The Troubles.3

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE TROUBLES

Over the course of the twentieth century, Northern Ireland was caught in a cycle of on-again off-again violence, as problems related to its cultural identity had given rise to political and social conflict. The conclusion of the Irish War of Independence in 1922 had resulted in the partition of Ireland into two governing areas: the twenty-six counties that make up the mainly Roman Catholic Republic of Ireland, and the six counties that make up the mostly Protestant Northern Ireland.4 While the Republic of Ireland became independent of the United Kingdom, the few counties that made up Northern Ireland chose to remain a subject of the British Monarchy. In the twenty years following World War II, Roman Catholics who lived in the mostly Protestant north faced open discrimination from the Protestant majority. Everything from workplace environments to the highest positions of government openly barred Catholics from achieving any notion of fair play. Even the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Lord Brookeborough, was notoriously bigoted, having gone on record that he would “not have a Catholic about the place.” He and many others in the Northern Irish government actively blocked Catholics from having a say in the government, and effectively turned the Catholic minority into second class citizens.5 In the 1960s, the international spread of civil rights movements had inspired the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland to peacefully protest the bigotry in their government, hoping for reform. The Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) formed to organize marches and forums to create equal opportunity in Northern Ireland. The marches were originally meant to be peaceful, and had the goal of creating reform through government channels. However, the peace marches and forums were often matched by counter protests by groups of Crown-loyal Protestants, and tensions between the two factions rose higher with each standoff. Adding gunpowder to the already large powder keg was the local government officials, who openly threw their support behind violent “counter protestor” groups. These groups were organized by Protestant Loyalist groups who wished to silence the whole situation before it grew out of hand. NICRA was undeterred however, and continued to plan marches despite the large opposition in both civilian and government groups. Each standoff was only one stone’s throw away from breaking out into a riot, and it was only a matter of time until the standoffs in fact did turn into riots. On October 5, 1968, the mostly loyalist Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) violently baton-charged a civil rights march on live television, causing widespread outrage. In response, a group believed to be the Irish Republican Army began a bombing campaign of target locations across Northern Ireland. As bombings and beatings broke out across the country, the Northern Irish government decided to call in the British Army to help them get a hold on the situation. On August 15, British soldiers arrived to cheers from Catholics, who believed that the army was called to act as a neutral mediating force. However, their jubilation turned to outrage when the British Army announced that they had only been deployed “in aid of the civil power.” In other words, the British army’s only goal was to suppress any dissident voices until the bigoted Loyalist regime regained control. The announcement had destroyed any belief that NICRA could achieve a peaceful resolution, and in 1970, many Catholics looked to more drastic measures.6

With the announcement of Britain’s support of the RUC and the Loyalist government, many young angry Catholics in Northern Ireland became disillusioned with any hope of reconciliation. Instead, they turned to the Irish Republican Army, a paramilitary group that sought reunification with the Republic of Ireland. Emboldened with new recruits, the IRA took a more violent approach to the fight against the Loyalist regime, and replaced the NICRA-sponsored marches and protests with bombing campaigns and “disappearances.” Each step the Northern Irish government took to suppress the bombings and riots actually bolstered IRA recruitment, creating a large and disorganized IRA that looked for blood over justice.7 Loyalist Paramilitary groups met the IRA in ferocity, looking to take revenge on massacres, killings, and bombings carried out by IRA groups. What once was a peaceful struggle for civil reform and equality had quickly devolved into an unceasing guerilla conflict. Over the next thirty years, the conflict’s daily killings and bombings made a large impression on the lives of all the Northern Irish people. Songs such as Zombie by the Cranberries characterized the exasperation many felt at the continued violence. The conflict saw the loss of over 3500 lives with over half of them being civilian.8 Peace negotiations were commonly dismissed by Republican groups to be fool’s errands due to the zero-tolerance policy Britain kept in regards to terrorists. Despite their public policy, Britain and multiple Republican groups attended under the table peace talks beginning around 1980. These peace talks caused division in the Irish Republican Army, as many felt that anything short of reunion with the rest of Ireland betrayed the very reason they were fighting. Despite many tense “deal-breaker” situations, and ceasefires so often giving way to gunfire, talks of peace eventually came to fruition after almost thirty years of conflict when, in 1998, the Good Friday Agreement was signed by almost all Northern Irish political parties. The agreement included provisions for Catholic representation and, should Northern Ireland pass a referendum for it, reunion with the Republic of Ireland.9 Despite the feelings of smaller splinter groups, most Irish Republicans felt happy with the agreement. However, seemingly absent from the document was any provision for amnesty for past crimes. As the new government of Northern Ireland formed, it became common knowledge that any who spoke out on actions during the Troubles was going to be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.

RECORDING HISTORY AND OTHER FOOLISH ENDEAVOURS

Recording all the chaos of the Troubles was an Irish journalist by the name of Ed Moloney. Over the thirty year span of the conflict, Moloney quickly became renowned for his documentation during Ireland’s struggle. After the conflict’s uneasy resolution in 1999, Moloney and other historians began visiting different universities, hoping to find a sponsor for his new project. This project aimed to record a series of interviews with members of both the RUC and the IRA, in the hopes of recording a complete history of both sides of the conflict. Despite the honest academic intentions of the project, “pent-up emotions,” and a “sense of personal loss lying barely below the surface” made a culture of tension in Northern Ireland that none dared disturb.10 Furthermore, legal prosecution could still follow any who admitted to being party to any paramilitary action during the Troubles. Because of the great risk, no university or historian wanted to touch it.

Moloney’s luck changed in 2001. Moloney had to fly all the way to the United States to speak with the head of the Burns Library at Boston College. There, he found an enthusiastic sponsor in Robert K. O’Neil, the head of Boston College Library.11 Due to the delicate nature of the subject, and a strict policy of silence implemented by Irish Republicans, Moloney successfully argued that there needed to be a point of trust for each side–a person for each side of the conflict that was known and trusted by each interviewee. To serve as a familiar and trusted face for the interviewees, former RUC member Wilson MacArthur and former IRA member Anthony McIntyre were recruited to conduct each interview for the project. Over the course of the next few years, the two veterans were busy gathering the stories from over 100 combatants in the Troubles. While the interviews contained important information to the people of Northern Ireland, the wounds were still too fresh to safely release the stories. Fearing the wrath of the notoriously secretive IRA, Moloney successfully argued that a set of rules had to be put in place to ensure the safety of all participants. First, each interviewee was referred to under a pseudonym, and only one person could have the entire key that detailed who was who. Secondly, the existence of the project was to be kept under lock and key. Those outside of the Boston College Library were not to be trusted or consulted with in regards to any knowledge of the project.12 This meant that everything, from the legal documents to the documentation and storage of the interviews, was kept secret from all Boston College experts, lawyers, and consultants. Finally, the stories were only to be released after the death of the teller, so as not to bring any prosecution down upon the interviewee. With the rules set in place, the project was kept safe in the Boston College archives until each interviewee had died. With the archives an ocean away in the United States and the conclusion of the last interview, the only thing left for the Belfast Project team to do was watch the obituaries.

A HOUSE OF CARDS

Problems with the Belfast Project did not show until the first interviews were released. In 2008, Brendan Hughes, a former IRA fighter, died. Following his death, recordings of his interview were quietly made available to the public. In 2010, Moloney released a book entitled Voices from the Grave, which told the stories of Hughes and others using a pseudonym. Thus, with a single book, Moloney singlehandedly started a chain of events that caused a worst-case scenario for the Belfast Project. In the following years, the existence of the Belfast Project was not only revealed, but political scandals and prosecutions haunted the project over the course of the next decade.

THE PROBLEM WITH SHOWING YOUR HAND

In the book, Moloney made several mistakes that caused the Belfast Project to lose credibility and caused the political state of Ireland to almost descend into chaos. The first mistake was with the release of the story. In the foreword of his book, Moloney not only made reference to the Belfast Project, but also thanked the personnel at Boston College for their help and included a foreword by O’Neill.13 Furthermore, while the tellers of the story had passed, those who were involved or were mentioned in the stories were still very much alive, leaving them vulnerable to exposure should someone connect the dots. Problems compounded as the details of Hughes’ testimony became more and more scrutinized. Hughes, and in telling his story, Moloney, made several references to a woman in 1972 whose disappearance was not only a heated subject in Northern Ireland, but was also still under investigation by the Police Service of Northern Ireland. This woman, Jean McConville, was a famous member of the “Disappeared,” a group of people who were presumably murdered by the IRA in the early ’70s.14 According to Hughes’ testimony, the kidnapping of McConville, a widow and mother of ten, was greenlit by a current politician named Gerry Adams. Shortly after, another interviewee, Dolours Price, was interviewed by Allison Morris of the Belfast-based Irish News, and revealed not only the existence of the Belfast Project to the general public, but also corroborated the story of Adams’ role in the disappearance of McConville. The interview all but confirmed the existence of the Belfast Project, and it became a priority to get the details of McConville’s murder. Before they could get justice for the McConville family, the Police Service of Northern Ireland first had to navigate the metaphorical maze that was the international courtroom.

THE LEGAL VIEWPOINT

Because the archives were in Boston, the Police Service of Northern Ireland technically did not have jurisdiction, and therefore could not gain access to the tape recordings. However, a treaty that was made between the United States and Great Britain in 1994 allowed the Police Service of Northern Ireland to send a request to the United States to subpoena the Belfast Project. According to the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT for short), each country retained the right to request information regarding case sensitive information.15 However, the MLAT also allowed provisions for denial of said request, provided the Requested Party finds the request to be “contrary to important public policy,” among other possible reasons. The first in a long series of legal problems lie in the aforementioned MLAT clause. In the United States, it had been believed since the nation’s founding that a journalist enjoys a right to confidentiality. Dubbed the journalists’ privilege, it was a commonly accepted idea that journalists could use this privilege to deny a federal request to expose secret informants.16 However, a Supreme Court decision in 1972, and a subsequent opinion piece by one of the presiding Justices, found that while reporter’s privilege was not federally protected under the Constitution, there was reason to believe that there were Constitutional provisions to protect the privilege.17 By 2010, some states had even passed laws that protected reporter’s privilege, but others offered no such legal protection. Because of the confusion over reporter’s privilege, and the added pressure of an international scandal, deliberations over whether or not the United States could even accept such a request weren’t answered until the next year.

PROJECT PRESSURE

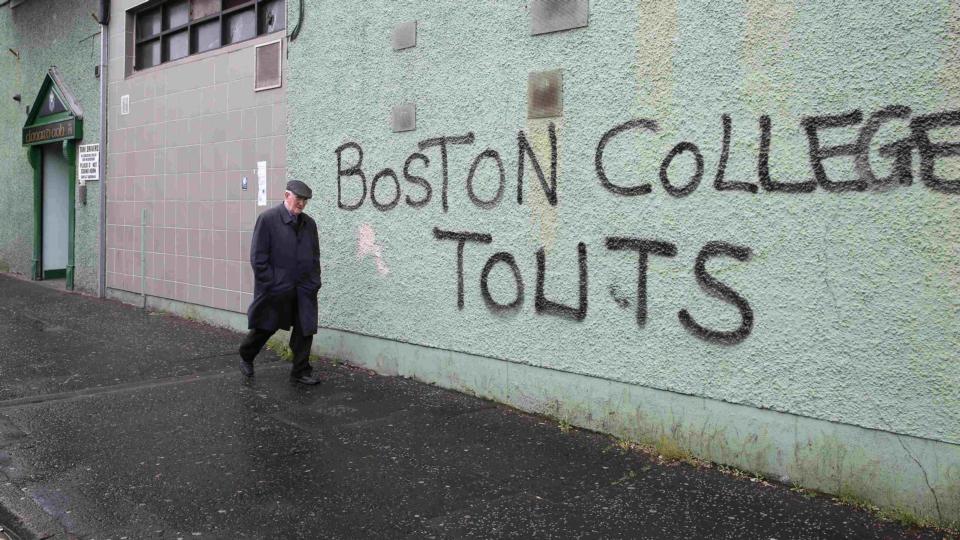

In 2011, conflict arose within the Belfast Project team when Boston College received a sealed subpoena for a “Belfast Project,” which was a project that, to the knowledge of most of the Boston College staff, did not exist.18 The Belfast Project at first tried to deny its existence, believing that it was “the better course to protect the interests of interviewees,” and just maintain ignorance. Despite the Belfast Project’s attempts to feign ignorance, the subpoena still stood strong, forcing McIntyre, Moloney, and Boston College to make separate efforts to stop the subpoenas. Initially, the subpoena had only asked for a limited number of testimonies: that of Hughes, and Dolours Price, who both admitted on record to having had a hand in the death of Ms. McConville. Since Hughes had already passed on, Boston College relinquished the tapes in accordance to their contract, much to the anger of Moloney and McIntyre. Over the course of the next few years, the legal battle for reporter’s privilege, the fiery passions of the Northern Irish people, and the precautions the Belfast Project had taken to maintain secrecy all crashed together, creating a giant wave of backlash and controversy that the Boston College staff was ill prepared for. Because of the alleged implication of Gerry Adams as a leader of the IRA, Moloney and McIntyre had been receiving death threats for their involvement with the project, and they were accused of being bad faith interviewers. Furthermore, in keeping the project secret, the two had unknowingly created a legal loophole that eventually destroyed any credibility that oral history projects like the Belfast Project had. Upon review of the legal contract that Mr. Moloney, Mr. McIntyre, and Mr. O’Neill drafted, it was found that the contract only protected secrecy to the extent of the American government.19 Boston College nonetheless resolved to file a motion to quash, despite the loophole, but to no avail. The subpoena would stand, and the files were to be transferred over to the Police Service of Northern Ireland. Because of these events, McIntyre and Moloney became highly critical of Boston College, believing that since the College had relinquished Hughes’ tapes, they might relinquish the rest of the records as well, and abandon the project.20 Trust between the team members continued to break down, to the point where Moloney suggested simply burning all records of the project. Eventually, after a long and tense legal battle, it was decided that an American judge would have to spend his or her holidays reviewing each and every interview contained in the Belfast Project archive to decide which was related to the murder of Jean McConville.21 Those that were deemed to be in relation to the McConville case were then sent to the Police Service of Northern Ireland to be prepped for prosecution, with the rest remaining in the Boston College archives. In the end, Judge Young only found that one of the tapes made direct reference to the McConville murder, but ten additional tapes made additional references to the crime. Furthermore, those eleven tapes were to be prepped for transcontinental transfer over to the Police Service of Northern Ireland. In 2014, the documents were out and the jury was in, as the eleven tapes were relinquished to the Northern Irish Police for court preparations.

WHAT WAS ON THOSE TAPES?

With the legal battle between Boston College and the U.S. Justice system finally concluded (more or less), the Police Service of Northern Ireland now had in its possession the eleven tapes that, hopefully, told the true story of Jean McConville. Back in Northern Ireland, the McConville murder had gained a massive audience, as it was found that the very popular politician Gerry Adams had been implicated in the controversial murder of McConville. Adams had recently been elected the president of the Republican political party Sinn Féin based on a reputation of making peace, and was commonly seen as the catalyst for the Good Friday Agreement. Contrary to his decades-long denial of any IRA connections, the tapes retrieved from the Belfast Project pointed to Adams as an early leader of the IRA in multiple interviews, including those of Hughes and Price. Specifically, they had said that Adams was the one who had greenlit McConville’s murder all those years ago.

The tapes also contained confessions of one of the killers of McConville, who was a Republican Army veteran by the name of Ivor Bell. In the recording, Mr. McIntyre and Mr. Bell discussed the killing of McConville, with both agreeing it was a war crime. Eventually, Bell explained that he was given the greenlight by Adams to kidnap and execute McConville. The tapes’ confession was enough to give the Northern Irish police reason to move on both Adams and Bell. In 2014, Bell and Adams were both arrested by the Police Service of Northern Ireland for questioning. Because the arrest was exactly one month before the election for Adams’ reelection, the act was vehemently condemned by Republican groups in Northern Ireland, believing the arrest to be a politically motivated attempt to discredit the Republican cause.22 Four days after his arrest, Adams was released from the PSNI without charge, much to the relief of Republican groups. Meanwhile, Bell soon learned in 2016 that he was going to stand trial for the aiding and abetting of murder.

THE TRIAL OF IVOR BELL — BELFAST PROJECT SENTENCED TO DEATH

The trial of Ivor Bell was the first paramilitary related jury trial since the introduction of the no jury Diplock trials of 1973. Because Ivor Bell was suffering from vascular dementia, the R v. Bell trial was delayed for over two years while lawyers argued whether or not he was able to stand trial.23 It wasn’t until October 2019 that Justice O’Hara called into session a trial of the facts due to Mr. Bell’s medical condition.24 Under the law of England and Wales, if a Court determines that a person is mentally or physically unfit to stand trial, then criminal proceedings cannot proceed. However, prosecutors do have the option of having the case heard as a “trial of the facts.” Much like a criminal trial, a trial of the facts sees the prosecution put forward evidence against the defendant before a judge and a jury, but unlike a criminal trial, the jury is not required to return a verdict of guilty or not guilty. Instead, the jury will decide on whether or not the accused actually committed the offense they are charged with. During the trial, signs of tension between the Northern Irish factions showed when an entire jury had to be dismissed due to reports of a juror being told that he or she should “reach the right verdict.”25 After dismissing the first jury, the Court returned to session with a new jury, and the prosecution made their opening statements.

The Prosecution argued that the tapes would prove that Ivor Bell had solicited, encouraged, or persuaded two other men to abduct, murder, and secretly bury Jean McConville. The defense took issue with the reliability of the interviews and whether or not the person alleged to be Ivor Bell, Interviewee Z, was in fact Bell. In regards to the first issue presented, it was revealed that the interviewer, Anthony McIntyre, and a good bunch of the interviewees had been part of a feud that arose when Adams entered peace talks with the British government.26 It was argued that, since Mr. McIntyre in particular had never been a fan of Adams’ proponents of peace, Mr. McIntyre purposely asked leading questions in an attempt to discredit Adams. Since Adams had been constantly mentioned, the Member of Parliament was called to the court to give his testimony. Rather expectedly, Adams maintained that at no point in time was he ever involved with the Irish Republican Army, explaining that the Belfast Project was “most suspect.” With a shadow of suspicion turned onto the entire Belfast Project, the court now turned to the Boston College librarian, professor Robert K. O’Neill. Prior to the trial, O’Neill had already made it clear that he strongly disapproved of the way McIntyre and Moloney handled the project.27 In his testimony, O’Neill went over the many failings of the project, going so far as to brand it as “deeply flawed because of the lack of proper consent of the interviewees.”28 O’Neill blamed the improper vetting of McIntyre and Moloney as the root cause of the projects problems. With all evidence presented, Justice O’Hara had finally come to a decision.

COURT CONCLUSION, AND NORTHERN IRELAND TODAY

Based on evidence presented in the case of R. v. Ivor Bell, it was found that the tapes were not admissible in court. The court found that McIntyre had purposefully selected members of the Irish Republican Army that had had a falling out with the Sinn Fein government party. McIntyre then asked leading questions in an attempt to sabotage and incriminate Member of Parliament Gerry Adams because of deep rooted grudges held against him.29 It was on this basis that the Court moved to exclude the Boston Tapes from evidence. This meant that no evidence remained tying Ivor Bell to the crime. With no evidence left for the prosecution to present, Justice O’Hara directed the jury to return “not guilty” verdicts. After a five year legal battle, the trial of Ivor Bell found the defendant not guilty, and tensions in Northern Ireland died down, at least for a little bit.

Even today, the damage caused by the era of the Troubles still lives in the sub-conscious of Northern Irish men and women. Every day, families who lost their mothers, fathers, brothers, or sisters shout for justice and closure, but are answered with silence. In the modern day, the division derived from the violent history of the Troubles has been agitated by the stresses of the Covid-19 pandemic and Britain’s exit from the European Union. This has caused the relative calm of post-Troubles Northern Ireland to abruptly end as young protestors in Belfast once again took to gasoline bombings and rioting.30 Meanwhile, the history of the Troubles fades with each passing day. Many of the old veterans of the Royal Ulster Constabulary and the Irish Republican Army are entering their seventies and eighties, and are now content with taking their stories to their graves. With each veteran’s passing, another aspect of their violent history becomes forever lost, preventing future generations from learning from their mistakes. To many of the paramilitary veterans, the Belfast Project served as another reminder to keep your mouth shut. The Belfast Project team’s failure to secure a trustworthy academic environment, and the bad publicity that came from McIntyre’s interviews serve as a long-term obstacle for future oral history projects in places plagued with division. The true tragedy of the Belfast Project lies in the material of the interviews. In the words of Judge Young, the American judge who reviewed all the interviews in 2014, the project has great historical merit, and is the result of years of hard-work and intensive labor. However, because of the controversies surrounding it, many simply dismiss the recordings as a biased and twisted view of history.

This article was definitely a long and difficult journey, and there was many a time that I didn’t think I would be able to finish a decent article from it. I want to thank my friend, Amanda Uribe, for her tremendous help and patience with my research article. Her continuous encouragement and hard-work kept me from losing my mind as I wrote and rewrote the article. Amanda was a light shining in the darkness, and I am forever grateful to her. Without her, I’m sure this article would never see the light of day. I also want to thank Dr. Whitener, who tolerated and supported my long winded rants about the Belfast Project after class, and was also a big help in putting this whole article together. His editing and his support helped me greatly. Overall, this article is the culmination of hours of research and I hope that you, the reader, enjoy the fruits of my labor.

- Laura Weinstein and Donald M. Beaudette, “Why a 1972 Northern Ireland Murder matters so much to historians,” Washington Post, November 6, 2019), https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/11/06/what-northern-ireland-legal-case-means-historians/. ↵

- R v. Ivor Bell – Application to Exclude The Boston Tapes Evidence (legal document, Belfast, 2019), https://www.judiciaryni.uk/sites/judiciary/files/decisions/R%20v%20Ivor%20Bell.pdf ↵

- Orla T. Muldoon, et al. “Religious and National Identity after the Belfast Good Friday Agreement“ in Political Psychology, Vol. 28, No. 1, (Feb. 2007), 99. ↵

- Christine Anne George, Whatever you say, you say nothing (Austin, Texas: University of Texas at Austin 2012), 12. ↵

- Brian Feeney, A Short History of the Troubles (Dublin, O’Brien Press, 2014), 1-9. ↵

- Brian Feeney, A Short History of the Troubles (Dublin, O’Brien Press, 2014), 9-16. ↵

- Brian Feeney, A Short History of the Troubles (Dublin, O’Brien Press 2014), 20. ↵

- Malcolm Sutton, “Sutton Index of Deaths,” CAIN (Ulster University, 2021), https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/sutton/tables/index.html . ↵

- The Northern Ireland Peace Agreement (legal document, Belfast, 1998, 11-15), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/136652/agreement.pdf . ↵

- Gerry Slater, “Confessions of an Archivist,” Journal of the Society of Archivists 29, no. 2 (2008): 141-142. ↵

- Ed Moloney, Voices from the Grave: Two Men’s War in Ireland (London: Faber and Faber, 2011), preface. ↵

- NPR Staff, “Who Killed Jean McConville? A Battle for IRA Secrets,” NPR (National Public Radio, July 15, 2012), https://www.npr.org/2012/07/15/156811081/who-killed-jean-mcconville-a-battle-for-ira-secrets. ↵

- Ed Moloney, Voices from the Grave: Two Men’s War in Ireland (London: Faber and Faber, 2011), preface. ↵

- Independent Commission for the Location of Victims’ Remains, “The Disappeared Home Page,” The Disappeared of Northern Ireland (Independent Commission for the Location of Victims’ Remains), accessed November 17, 2021, http://thedisappearedni.co.uk/. ↵

- “Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty,” opened for signature January 6, 1994. Treaty Series: TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL ACTS, 96-1202 (1994), https://irp.fas.org/world/uk/us-uk-mla.pdf ↵

- John O. Omachonu and Deborah Fisher, “First Amendment Encyclopedia,” in First Amendment Encyclopedia (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2009), https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1146/reporter-s-privilege. ↵

- Branzburg v. Hayes, 408 U.S. 665 (1972) ↵

- Christine Anne George, Whatever you say, you say nothing (University of Texas at Austin 2012), 32. ↵

- R v. Ivor Bell – Application to Exclude The Boston Tapes Evidence (legal document, Belfast, 2019), https://www.judiciaryni.uk/sites/judiciary/files/decisions/R%20v%20Ivor%20Bell.pdf ↵

- Christine Anne George, Whatever you say, you say nothing (University of Texas at Austin 2012), 45. ↵

- Democratic Progress Institute, The Belfast Project: An Overview (London: Democratic Progress Institute, 2014), 18, https://www.democraticprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Belfast_Project-ENG-version.pdf ↵

- Democratic Progress Institute, The Belfast Project: An Overview (London: Democratic Progress Institute, 2014), 19, https://www.democraticprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Belfast_Project-ENG-version.pdf ↵

- Michael McHugh, “McConville murder trial: Delay in Ivor Bell medical reports,” Belfast Telegraph, March 4 2017). ↵

- Vincent Kearney, “What Ivor Bell Said in the Boston Tapes,” RTE.ie (Raidió Teilifís Éireann,) October 17, 2019, https://www.rte.ie/news/2019/1017/1084044-ivor-bell-boston-tapes/. ↵

- Allison Morris, “Allegations of Jury Tampering in Ivor Bell Case,” The Irish News, October 18, 2019, https://www.irishnews.com/news/northernirelandnews/2019/10/18/news/allegations-of-jury-tampering-in-ivor-bell-case-1741993/. ↵

- Patrick Radden Keefe, “Where the Bodies Are Buried,” The New Yorker, March 9, 2015. ↵

- Richard Weir, “Boston College Knocks Own Project That Implicates Gerry Adams,” Boston Herald, November 18, 2018, https://www.bostonherald.com/2014/05/06/boston-college-knocks-own-project-that-implicates-gerry-adams/. ↵

- Ashleigh Mcdonald, “Ivor Bell Cleared of Involvement in Murder of Jean McConville,” BelfastLive, October 17, 2019), https://www.belfastlive.co.uk/news/belfast-news/ivor-bell-cleared-jean-mcconville-17099074. ↵

- Ashleigh Mcdonald, “Ivor Bell Cleared of Involvement in Murder of Jean McConville,” BelfastLive, October 17, 2019, https://www.belfastlive.co.uk/news/belfast-news/ivor-bell-cleared-jean-mcconville-17099074. ↵

- Rick Gladstone and Peter Robins, “The Ghosts of Northern Ireland’s Troubles Are Back. What’s Going on?,” The New York Times, April 12, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/12/world/europe/Northern-Ireland-Brexit-Covid-Troubles.html. ↵

6 comments

Elliot Avigael

This article was an amazing read. I always knew there was trouble in Northern Ireland but never really dove into the meat and potatoes of it. Truth be told, Northern Ireland has been difficult to tame since the days of Ulster and the Ui’ Niell, at a time when Ireland had not been united under one king. It’s surprising to think that this took place not too long ago and in many ways, still continuing.

Rigel

Amazing and interesting article! This is the first time I have heard of the Belfast Project, and I am glad I learned it from this article considering how well written it is. Your article is very informative, and I love the way it is formatted to make us readers understand the events of the Troubles. It is disappointing to know that the Belfast Project was a failure considering it had potential as oral history, makes one wonder if it could have ever been successful.

Seth Roen

It baffles me how many ripples the Ireland War of Independents caused in the year to come. Just as you pointed out with Northern Ireland, and the mismanagement the government did to cause needless bloodshed that lasted far too long. You also pointed out how dangerous a university is and why in some places are so heavily controlled because so often, reforms start in these places of higher learning.

Madison Goza

I loved how passionate you were about your subject, it definitely shone throughout your entire article! Visually and stylistically, I liked your use of subheadings; I think it broke up the narrative well into distinct parts. Opening your article right in the moment with a recent event to set the stage was a strong choice. You carefully explained a complex topic with special attention to the nuances of the legal battle, loopholes, and questions of journalistic integrity. Great article!

Carlos Hinojosa

This was actually very interesting because I don’t know much about Irish History and what it means to them. The only thing i know is that they don’t like England and that they had a rebellion. So, this was very informative for me due to my lack of knowledge, and I consider this very interesting. This article was very well made, and I hope to read more from you.

Andres Ruiz

This article was definitely a long and difficult journey, and there was many a time that I didn’t think I would be able to finish a decent article from it. I want to thank my friend, Amanda Uribe, for her tremendous help and patience with my research article. Her continuous encouragement and hard-work kept me from losing my mind as I wrote and rewrote the article. Amanda was a light shining in the darkness, and I am forever grateful to her. Without her, I’m this article would never see the light of day. I also want to thank Dr. Whitener, who tolerated and supported my long winded rants about the Belfast Project after class, and was also a big help in putting this whole article together. His editing and his support helped me greatly. Overall, this article is the culmination of hours of research and I hope that you, the reader, enjoy the fruits of my labor.