Imagine going back in time to World War II. You’re somewhere in the battle zone staring up at a cloudy gray sky, hoping you would be going home soon. But you didn’t know what home meant as your hands kept squeezing the weapon that was made to save some lives by ending others. This was the world now, covered in darkness and remembered in death. It never felt like it would never end for you and for the millions of others participating in the war. But then you remembered a story your mother read to you when you were a child. You slowly would press your lips together and start to whistle. It was a familiar tune that a yellow bear would blow when he and a little boy walked through the woods together.

The tune you were whistling was made by a man unlike you or I; he was a creator of a story that would be known to children for decades to come. But the 1940s is too far in the future for the beginning of this story. We need to go back to the Great War, where a young hesitate solider named Alan Alexander Milne stood with his countrymen in the trenches along the Western Front. Young Alan Milne was a writer who had been forced into a role he truly never wished play. He hated the idea of war. But fate can be cruel, and from 1914 to 1918, his eyes were bombarded with only death, hopelessness, and darkness.1 War can change how a person sees the world, and that is what it did to Milne. The colors of black and red stained his eyes and would be burned into his mind when he eventually came home. Once Alan did returned to his civilian life, he suffered severely from what they called Shell Shock. Because of those experiences in the trenches, he slowly drifted away from his wife and son. Milne couldn’t get over what he saw and experienced in those trenches. But what was worse was that he didn’t understand how to cope.

So, Milne would sit at home and try to make some attempt at his new-found project, but he usually only came up with simple verses that he had some friends read to judge how they felt about them.6 But Milne wasn’t getting anywhere with only having more people suggest more topics to think about. What was he going to write about? A children’s book? Who and what? When and where, and why? Milne was starting to get stumped, but luckily he wasn’t alone anymore. On the floor above him, a child quietly played in the nursery with a toy bear only one year younger than he was.7

One day, as Milne was sitting at his desk, he brought his sharp eyes away from his work, noticing someone that he found himself distant from and who went by the name, Billy Moon. If you asked anyone close to the Milne’s family, they would say that their only son was named Billy Moon, but in fact, he wasn’t.8 His actual name was Christopher Robin Milne. And suddenly, in his father’s mind, an idea was forming. Alan slowly started to observe how Christopher played with his stuffed animals. But more importantly, he observed how the little boy gave them life. He would shout and dance with a smile on his face that would make anyone want to join in too. Christopher would grab his soft yellow teddy bear’s paw and race into the five-hundred-acre woods that surrounded their home. Alan Milne would see his son run with eyes full of belief, so that if you saw what he did, you could watch all the other toys run after him.

At night, Milne started to talk to Christopher about his toys, and how each response he made to his toys made him feel as though they were real, that all the laughs and complaints they made really did happen. One instant, the yellow bear got so angry Milne and Christopher that they found him face first on the floor pouting: “… Pooh was missing from the dinner-table which he always graced. She asked where he was. ‘Behind the ottoman,’ replied his owner coldly. ‘Face downwards. He said he didn’t like When We Were Very Young.’ Pooh’s jealousy was natural. He could never quite catch up with the verses.”9

Soon, father and son started spending a lot of time together. Milne would even join his son into the woods. He saw how Christopher jumped and yelled as if expecting something to yell back, and there were times when it felt like there was a soft gentle voice echoing towards the pair.10 The clock was still ticking for Alan Milne to produce something to publish, and he eventually got away from small verses to writing some short stories of Christopher Robin and his friends. Milne even started to read them to Christopher at the end of the day, jotting down whatever comment Billy or his teddy bear had to offer.11 Alan Milne was not only bonding with his son he barely knew, but he was also, maybe without even realizing, writing away some of the ghosts that followed him back from the war.

What is better for a child? A story that has an end, or a book filled with simple tales whose messages will change as you grow older? Before he could continue to write, there had to be a home for everyone, and why not where all the playing actually took place. Alan Milne based the foundation of Hundred Acre Woods on the forest 500 Acre Woods (Ashdown Forest), but that was not all he kept the same. For the characters he went with his son Christopher Robin (leaving out the last name) and the toys he played with, and eventually other children would as well: Piglet, Kanga, Roo, Tigger, Eeyore, then of course Winnie-The-Pooh. Still, Alan Milne was the creator of this world and he added some of his own characters known to us as Rabbit and Owl.12

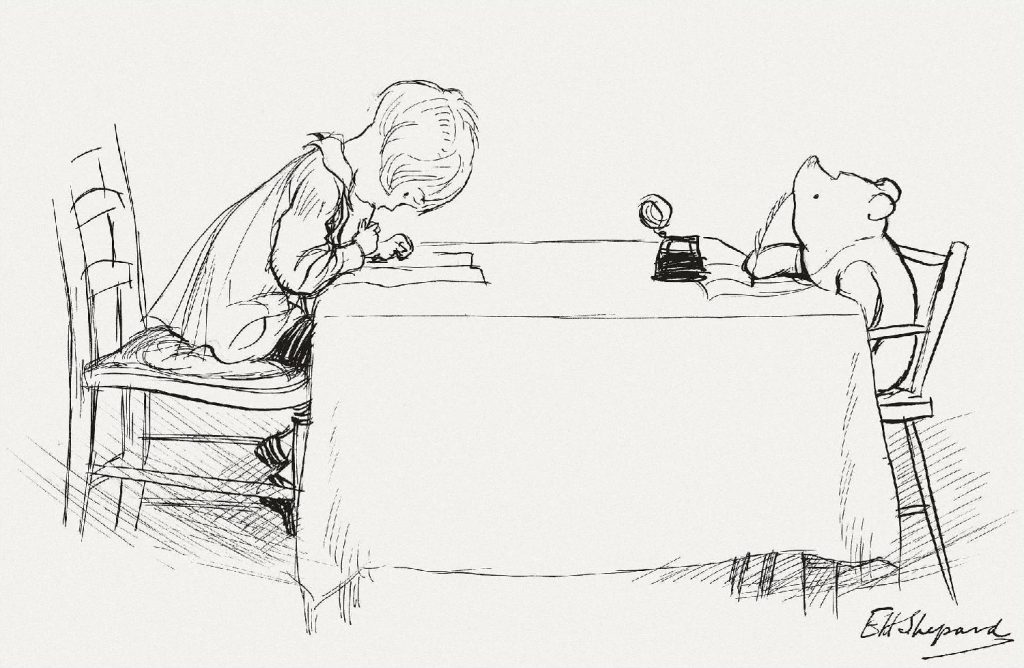

It still wasn’t over yet and Alan Milne had a lot of work to do. He continued writing short verses along with reading them to his son to make sure each chapter and each new adventure lived up to the “real” characters’ approval. And he didn’t stop there, Milne went on to have his perspectives in the writing shift from first person to third person, then lastly to second person.13 He wanted the reader truly to feel a part of their private world. After enough stories had been compiled together for a book, he put them in the order he thought best before meeting with Ernest H. Shepard, who would eventually come to illustrate all three books that Milne would publish based on his son. What made Shepard’s work so memorable is that even though he drew them as toys, he made them feel real as he kept the character Christopher Robin looking like Milne’s only son.14 Even when Disney bought Winnie-The-Pooh and created their own version of the characters, Shepard’s work is still symbolizing the realness of childhood.

The book was published on October 15, 1926, and it was called Winnie-The-Pooh after the name of the gentle teddy bear that changed so often before the young Christopher Robin Milne decided to settle on the title that would be written in history. England fell in love with the stories, and became obsessed with how there was truthfulness in each word and in every thought muttered on each page. This truthfulness would eventually lead to a variety of complications between Milne and his son, who would develop resentment towards his father for “stealing his childhood.”15 But both men were cast into the shadow of Winnie-The-Pooh because of how much the world needed him. The second decade of the twentieth century was a time of death, and a new war was not far off. Winnie-The-Pooh, Now We Are Six, and The House at Pooh Corner were all people had that reminded them that there used to be a better place, an enchanted place where you walked on the ground and as the leaves would snap under your feet, a little yellow bear would be eating some honey, and hearing the crackling of the leaves would decide to leave some honey for you too, if he didn’t eat all first.

- Alan Milne, Autobiography: A. A. Milne (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1939), 247-248. ↵

- Alan Milne, Autobiography: A. A. Milne (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1939), 247-245. ↵

- Alan Milne, Autobiography: A. A. Milne (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1939), 276. ↵

- Alan Milne, Autobiography: A. A. Milne (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1939), 280-281. ↵

- Christopher Milne, The Enchanted Places (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1974), 36. ↵

- Alan Milne, Autobiography: A. A. Milne (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1939), 278-281. ↵

- Christopher Milne, The Enchanted Places (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1974), 76. ↵

- Alan Milne, Autobiography: A. A. Milne (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1939), 278. ↵

- Christopher Milne, The Enchanted Places (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1974), 63. ↵

- Christopher Milne, The Enchanted Places (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1974), 63. ↵

- Alan Milne and Ernest H. Shepard, Winnie-The-Pooh (New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1926), 160-161. ↵

- Christopher Milne, The Enchanted Places (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1974), 76. ↵

- Alan Milne and Ernest H. Shepard, Winnie-The-Pooh (New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1926), 3-22. ↵

- Alan Milne and Ernest H. Shepard, The House At Pooh Corner (New Work: Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1928), 73-75. ↵

- Christopher Milne, The Enchanted Places (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1974), 166. ↵

41 comments

Robert Freise

I am sort of familiar with the cartoon Winnie the Pooh. I did not know that when he developed the cartoon, he was facing WW2. It must have been really hard to combat the stresses of the war and having to formulate an article at the same time. It really amazes me that he was able to do that. This article gave me a bigger picture on how Winnie the Pooh came to be and how the man who wrote it was in WW2.

Indhira Mata

Without finishing the first paragraph I knew the article was going to be about Winnie the Pooh. I did not know that the creator of him was forced to become a part of the war. He was scared and did not like the idea of him, so then his creative mind helped him come up with our yellow bear friend. That is why Pooh helps the boy out of the woods where the battles would take. Like always our childhood stories surprise us with their roots.

Alyssa Garza

Winnie the Pooh was my favorite show to watch early weekend morning but I never knew that the story was inspired during World War II. In a way it makes sense now because each character has a different personality, and, in a way, it makes me think about if each character is a sort of different stages of what the author went through during the war and after he came back to civilization.

Cooper Dubrule

I thought it was as brilliant to start this article with a scenario that helps the reader to better relate to Alan Milne. As a kid I watched Winnie the Pooh so it was interesting to get background information about what brought this idea together. Alan Milne’s work was impressive and now even more so that I know what he went through and the process of it all.

Daniela Cardona

I never really watched Winnie the Pooh when I was younger, but never the less I really liked this article. I had no idea that in a way in originates to World War 2. Something beautiful really came out of the dark. In that, it was made for families by families. I loved that it brought people together in the making as well as after production. This was a really sweet article.

Katherine Watson

To think that during an era where the world was feeling the effects of the depression and the world itself seemed to be gloom above everything else, and then there were people like Alan Milne who still found a reason to smile. As a major Disney fan and a cast member, I almost feel like a disgrace to the company to not have known that Christopher Robin and Winnie the Pooh are based on real people before this moment. I use to read the novels growing up, but it has much more meaning to me knowing that these books brought some sunshine during a time where people really needed it.

Antoinette Johnson

I loved Winnie the Pooh growing up. I always wondered where the idea came from. I think that children’s book like Winnie the Pooh help children have comfort in the world they are growing into. Winnie the Pooh helped Alan connect with his son through his toys. Child tales engage children and really let the imagination flow. Alan had a tough time after the war straying away from his wife and so, but he was able to come back through, his children’s story Winnie the Pooh.

Pamela Callahan

I think it’s interesting how Milne was able to take something that happens everyday all around the world and turn it into something that is now so popular. The imagination of little children is such a powerful thing and I think basing a children’s story off of something that he recognized in his own life was a brilliant idea. Winnie the Pooh is such a popular story today and it will most likely continue to be for years to come.

Nathalie Herrera

Winnie the Pooh was always one of my favorite books. It was interesting to read how these characters were derived from and the inspiration the followed Alan Milne to this. The beginning of this article had a powerful hook and was engaging throughout. Good use of descriptive details to understand the thought process and inspiration of Winnie the Pooh. Very well written!

Gabriela Ochoa

this was a really great article very descriptive and catching. Like most I have read the stories of Winne the Pooh and friends but never knew the origin was from a man that was in WWII. For him to be able to go from shell shocked to writing stories and poems is amazing. I’m glad that by writing the stories he was able to become closer to his son and regain that relationship.