Before 1972, female athletes were not permitted to run in any marathons beyond 1,500 meters. That changed in 1972 when women could officially run the Boston Marathon. This was no easy achievement. The person who began the movement to change the rules set by the Amateur Athletic Union, a governing sports body, was Katherine Switzer, who was a 20-year-old Syracuse University student. With the help of her coach Arnie Briggs, Katherine ran the Boston Marathon on April 19, 1967, becoming the first woman to officially run the Boston Marathon and proving to the world women could participate in endurance sports.

From her teen years, Katherine Switzer was always a determined teen, which came with the territory of being the daughter of a U.S. Army major. Schweitzer was born in Amberg, Germany on January 5, 1947. She later moved in 1949 to Fairfax County, Virginia with her family. This is where she discovered sports of all kinds, including field hockey and basketball. Her main passion was her ability to run, and she would run a mile a day. This fitness that she trained her body to endure followed when she took up track at Lynchburg College, where she participated in short-distance track events, which women were allowed to participate in at the time.1

This was not enough for Switzer. So, in 1966, she transferred to Syracuse University and began training unofficially with the men’s cross-country team. This is where she first met Arnie Briggs, the coach that would help her reach her goal of running in the Boston Marathon. Arnie Briggs had been coaching the Syracuse University cross-country team for years before Switzer arrived. He had previously been the university mailman and had a total of fifteen Boston Marathons under his belt. Instead of rejecting or isolating Switzer, she was taken under Arnie’s wing, and she trained closely with him. He was excited to see a woman in endurance sports. What lead Switzer to phantom the idea of running the Boston Marathon was the never-ending tale she heard from Arnie. When Arnie would train her during evening sessions, he would recount the famous Bostons. Switzer loved to listen to the stories, but one evening she finally hit her limit and yelled “Oh, let’s quit talking about the Boston Marathon and run the damn thing!” He countered with “No woman can run the Boston Marathon.” What made Switzer angry was hearing about a woman named Roberta Gibb who had previously completed the Boston Marathon the year before. Hearing this, he said, “If any woman could do it, you could, but you would have to prove it to me. If you ran the distance in practice, I’d be the first to take you to Boston.2

Hearing this, she was determined to prove that she could make it to the Boston Marathon and complete it. So she began her intense training to prove to Arnie that she could do it. Three weeks before the marathon, Switzer was running 26-mile trial runs with Arnie. Over the years, she had built up stamina, due to the constant running every single day from her teen years to the present in 1967. She was sure that she could run the marathon and felt that she could excel at it. With this in mind, she asked Arnie if they could increase the training by five miles, just to reassure herself that she could complete the Boston Marathon as planned. This meant that the trial run for the sessions would be a 31-mile run. The first time that she and Arnie completed the run, Arnie passed out cold after the run. She had proven that she could hold her ground and complete a 31-mile run. Arnie gave permission the next day for her to compete in the Boston Marathon, but only if she was able to compete legally.[3. Kathrine Switzer, “The Real Story – Kathrine Switzer – Marathon Woman,” Kathrine Switzer, January 15, 2013, https://kathrineswitzer.com/1967-boston-marathon-the-real-story/.]

With the go-ahead, preparations were made to try and find a way to compete without breaking any rules; otherwise, she would find herself in trouble with the Amateur Athletic Union. To find a loophole for her to compete, they analyzed the rule book and entry form to see if they could use it against that AAU. They did in fact find a loophole. Even though female athletes were dismissed on entering, no one from the AAU had put it in writing. The way she was going to get in was to show that there was no mention of gender restrictions within the AAU rule book or on the entry form. Using the loophole, she was able to pay the $2 cash entry fee and sign up under the name “K.V.Switzer.” The next step was to get a fitness certification from her university. And with that, she was all set for Boston.3

One week before the race, Switzer’s boyfriend, Tom Miller, aka “Big Tom Miller,” a former All-American football player and nationally rated hammer thrower, declared that he would also be running in the Boston Marathon. He announced that he was not going to train because, if a girl could run it, then he shouldn’t have any trouble. What an egotistical and arrogant male phrase to use! That cascaded a ripple effect that caused John Leonard, another cross-country teammate, to join the journey to Boston.4

The main purpose of her goal to reach Boston and compete in the Boston Marathon was not to make history; it was simply to run her first marathon. When Arnie, Tom, John, and Switzer arrived in Boston, Arnie, in his excitement, decided to drive the course of the marathon to show them all the monuments and buildings they would pass while running the Marathon. In his excitement, he did not realize that this did more good than bad, because this increased the anxiety of the race for Switzer. In her panic, she called her parents, and her father reassured her with “Aw hell, kid, you can do it. You’re tough, you’ve trained, you’ll do great!”5

The support from her father helped her through half of her anxieties and worries, but the other half consisted of concerns about unpredictable possibilities, like what could happen to her body during the marathon, uncontrollable bladder or bowel movements, or accidents with persons in the race, or with spectators. But a major concern she had was that she was a female athlete competing in a presumed male-only event.6

There was freezing rain, wind, and sleet on the morning of the race, but she paid no mind to it, due to her training in the same kind of weather. Switzer made her way to Hopkinton High School, where they received the two number bibs each, having been pre-registered as a team. When her bibs were pulled out, her body was taken over by goosebumps. She could not believe that it said her name “K. Switzer” in print beside her number “261.” In total, there were 741 people participating in the race. It was a huge race. She pinned her bibs to her sweatshirt and began to warm up.7

During the warmup, everyone was focused on the run, but some did notice that she was a woman and most of those runners said encouraging and welcoming things to her on the way to the starting line, like “Gosh, it’s great to see a girl here!” “Can you give me some tips to get my wife to run? She’d love it if I can just get her started.” These helped her focus and feel welcomed among the rest of the runners. Even though Tom made some not-nice remarks about her lipstick, she battled because she always wore lipstick and kept her lipstick on even though he believed she should take it off.8

They reached the gate area, where running officials were checking off bibs. No one paid any mind and she was checked off and sent to the back of the field to prepare for the start of the race. Once again, male runners were ecstatic to see that they had a woman in their presence. They said more words of encouragement and even asked to take pictures with her. Running officials were making announcements. The crowd of runners huddled together for the start of the race. The gun went off, and they were off at last: 26.2 miles to go.9

The race was going fairly well overall until Switzer passed the two-mile point. That was when the chaos unfolded. The Boston Marathon typically brings in all kinds of runners, so naturally, there would be press, and with the press came press trucks. The press trucks passed by the trio, but did a double take when they realized that “261” was a woman. They began filming Switzer and shouting questions at her: What are you doing in the race? What are you trying to prove? The chaos of the press truck alerted running officials, which caused a busload of officials to show up right next to the press trucks.10

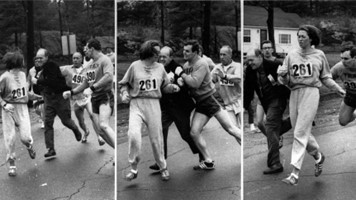

Jock Semple was born in Scotland, immigrated to the U.S., and was a man of reputation. He had run the Boston Marathon on multiple occasions himself, and he later became a volunteer director of the marathon. He carried the marathon from the 1950s to the 1980s. Without his passion for the marathon, it likely would have not survived the years after World War II. But Semple is more remembered today as the madman that ran off the runner’s official truck and tried to pull Switzer out of the race.11 . The reason for his outburst towards Switzer was that he was being teased by the press crew. They said that there was a “girl” in his race, and he just snapped and attacked her.

“He ran up behind me, and I heard his leather shoes at the last minute—you can hear the difference—and when I turned, this fierce face was right in my face and he screamed at me and said: ‘Get the hell out of my race and give me those numbers!’ And he’s ripping at my numbers and trying to pull them off.”12

Semple continued to chase her and take her bibs, and Arnie attempted to intervene and was assaulted by Semple as well. He continued to grab at Switzer, and Tom Miller pushed him away from her so that she could continue to run. That sequence of moments was captured by the press, and that footage helped change women’s running forever. The men that had supported and encouraged her at the very beginning of the race created a protective barrier around her. Tom Miller had realized what he had done, and that he would get kicked out of the AAU. He blamed Switzer for ruining any chance he had for the Olympics and left her during the race. Even though the entire encounter with Semple was a horrifying experience for Switzer, she continued on because she knew that if she quit, she would not only quit on herself but on all female athletes; so she ran. Nearing the end, she threw everything from the anger she had for Semple and the fear that she had done something wrong, to the nervousness of the 35km left in the marathon. The only thing she focused on was her determination to finish the race no matter what. She, Arnie, and John finally crossed the finish line at 4 hours and 20 minutes. She became the first woman to run the Boston Marathon as a registered woman, thereby becoming the official face of women’s running.13

When they finished the race no one cheered for them. Of course, with such a national viewing of what Switzer did, there would be a backlash for such an event. The backlash affected all women athletes when the Amateur Athletic Union banned women from running in the marathon. This made Switzer strive with determination to change the rules that the AAU had placed. Kathrine and other women campaigned vocally for women’s rights to run in marathons. This battle ended five years later, in 1972, when women were officially allowed to run the Boston Marathon. That year, Switzer went back to race in that marathon, where she met Jock Semple once again. He apologized to her, and took a picture with her, kissing her cheek. This was of importance due to the fact that the picture had the headline ‘The end of an era’ meaning that if a director of the Boston Marthan excepted women into his race, then everyone should follow, and they did. Women were accepted into endurance sports after that.14

After her accomplishment of running the Boston Marathon in 1967, she began to increase her endurance by running 110 miles a week in 13 weekly training sessions. She began to be invited to run in many different races, often as the first and only woman. Kathrine has a total of 41 marathons under her belt, including the 1974 New York City Marathon, which she won. In 1975, she ran the Boston Marathon in two hours, and 51 minutes, placing third among American women and sixth overall.15

She continues to compete in marathons today, just not as competitively as she use to. She changed her focus to a career in sports marketing, broadcasting, and influencing people in both fitness and business after a successful athletic career and in line with her commitment to improving conditions for women athletes. Switzer made the decision in 2004 to devote most of her substantial energies to writing, speaking, and, to a lesser extent, television broadcasting, all of which she had been doing on a part-time basis for the previous 25 years.16 In 2015, Kathrine, with the help of Edith Zuschmann, created a global network that helps women to find their own 261 Fearless Moments.17 To continue to help women running initiatives, she published three books: her first book, Running and Walking for Women Over 40, was first published in 1997. In 2005, 26.2 Marathon Stories, co-authored with her husband Roger Robinson, was published, followed in 2007 by her memoir Marathon Woman published in 2009.

- “Kathrine Switzer A Pioneer In Women’s Sports,” New York Road Runners, https://www.nyrr.org/about/hall-of-fame/kathrine-switzer. ↵

- Kathrine Switzer, “The Real Story – Kathrine Switzer – Marathon Woman,” Kathrine Switzer, January 15, 2013, https://kathrineswitzer.com/1967-boston-marathon-the-real-story/. ↵

- Eliza Buzacott-Speer, “50 Years Ago Women Weren’t Allowed to Run Marathons,” ABC News, March 24, 2017, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-25/kathrine-switzer-50-years-ago-women-not-allowed-to-run-marathon/8287576. ↵

- Kathrine Switzer, “The Real Story – Kathrine Switzer – Marathon Woman,” Kathrine Switzer, January 15, 2013, https://kathrineswitzer.com/1967-boston-marathon-the-real-story/. ↵

- Kathrine Switzer, “The Real Story – Kathrine Switzer – Marathon Woman,” Kathrine Switzer, January 15, 2013, https://kathrineswitzer.com/1967-boston-marathon-the-real-story/. ↵

- Kathrine Switzer, “The Real Story – Kathrine Switzer – Marathon Woman,” Kathrine Switzer, January 15, 2013, https://kathrineswitzer.com/1967-boston-marathon-the-real-story/. ↵

- Kathrine Switzer, “The Real Story – Kathrine Switzer – Marathon Woman,” Kathrine Switzer, January 15, 2013, https://kathrineswitzer.com/1967-boston-marathon-the-real-story/. ↵

- “Kathrine Switzer A Pioneer In Women’s Sports,” New York Road Runners, https://www.nyrr.org/about/hall-of-fame/kathrine-switzer. ↵

- “Kathrine Switzer A Pioneer In Women’s Sports,” New York Road Runners, https://www.nyrr.org/about/hall-of-fame/kathrine-switzer. ↵

- Tejas Kotecha, “Kathrine Switzer: First Woman to Officially Run Boston Marathon on the Iconic Moment She Was Attacked by the Race Organiser,” Sky Sports, https://www.skysports.com/more-sports/athletics/news/29175/12475824/kathrine-switzer-first-woman-to-officially-run-boston-marathon-on-the-iconic-moment-she-was-attacked-by-the-race-organiser. ↵

- Amby Burfoot, “Who Was That Guy Who Attacked Kathrine Switzer 50 Years Ago?,” Runner’s World, April 10, 2017, https://www.runnersworld.com/news/a20852681/who-was-that-guy-who-attacked-kathrine-switzer-50-years-ago/. ↵

- Tejas Kotecha, “Kathrine Switzer: First Woman to Officially Run Boston Marathon on the Iconic Moment She Was Attacked by the Race Organiser,” Sky Sports, https://www.skysports.com/more-sports/athletics/news/29175/12475824/kathrine-switzer-first-woman-to-officially-run-boston-marathon-on-the-iconic-moment-she-was-attacked-by-the-race-organiser. ↵

- Eliza Buzacott-Speer, “50 Years Ago Women Weren’t Allowed to Run Marathons,” ABC News, March 24, 2017, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-25/kathrine-switzer-50-years-ago-women-not-allowed-to-runmarathon/8287576. ↵

- Tejas Kotecha, “Kathrine Switzer: First Woman to Officially Run Boston Marathon on the Iconic Moment She Was Attacked by the Race Organiser,” Sky Sports, https://www.skysports.com/more-sports/athletics/news/29175/12475824/kathrine-switzer-first-woman-to-officially-run-boston-marathon-on-the-iconic-moment-she-was-attacked-by-the-race-organiser. ↵

- Kathrine Switzer, “Accomplishments – Kathrine Switzer – Marathon Woman,” Kathrine Switzer, December 22, 2012, https://kathrineswitzer.com/accomplishments/. ↵

- Kathrine Switzer, “Accomplishments – Kathrine Switzer – Marathon Woman,” Kathrine Switzer, December 22, 2012, https://kathrineswitzer.com/accomplishments/. ↵

- “All about 261 Fearless the Global Running Network: 261 Fearless,” 261 Fearless, accessed May 9, 2023, https://www.261fearless.org/about-261/. ↵

4 comments

Andrew Ponce

Congrats on getting this article published. Article such as this touch the hearts of many people within the passion of equity. It is interesting to hear the story of how a woman had to truly fight for a place in athletics. This article does more than teach the history of women’s sports. It teaches the history of determination and drive. This article showcases these attributes in a way that connects to the reader. Very interesting to learn about this event and who the face of Women’s Athletics is. Amazing job, Iris!

Andrew Ponce

Hello Iris! This article touches the hearts of many people within the passion of equity. It is interesting to hear the story of how a woman had to truly fight for a place in athletics. This article does more than teach the history of women’s sports. It teaches the history of determination and drive. This article showcases these attributes in a way that connects to the reader. Very interesting to learn about this event and who the face of Women’s Athletics is. Great work.

Gaitan Martinez

It still intrigues me that by 1920 both men of color and women had the right to vote, but still weren’t treated equally. They heavily suffered up until the Equal Rights Amendment was in the 70’s. Although it did improve equality, improvements were still needed. Hearing all the achievements that Katherine Switzer was able to achieve is very heartwarming because its crazy how women weren’t able to run a marathon. It’s a marathon! It’s just running.

Ray Jimenez

Great article!