It is the year 60/1 CE. The Governor of Roman Britain Gaius Suetonius Paulinus stands before his men, a force nearly 10,000 strong, staring down the Iceni Warrior Queen Boudicca and her army of 230,000 savage Celtic warriors.1 The absolute destruction wrought by the Britons would need to be ended here, as he had naught the food to continue evading battle.2 Paulinus could hear Queen Boudicca speaking to her army, decrying the Roman occupiers. He could hear her recounting the suffering experienced by her and her daughters at the hands of the Romans. She cried out that the gods themselves would give them justice over the cowardly Romans, who had avoided confronting them until now. They, in their numerical superiority, would certainly crush the Roman Legions where they stand, finishing with the ultimatum that “This is a woman’s resolve; as for men, they may live and be slaves.”3 Paulinus knew that Boudicca’s monologue was intended to demoralize his men just as much as it was intended to invigorate hers. He needed to address his men and rally them for the coming fight; thus he rode forth and prepared to speak.

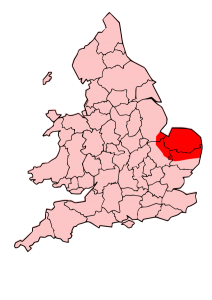

To understand how Paulinus found himself in such a desperate situation, we must look back to the year 47 CE. The Governor at the time, Ostorius Scapula, had instituted a handful of unpopular policies that heightened Briton resentment toward their Roman overlords, the first being the levying of huge taxes on the conquered and allied Briton tribes. Britain was proving to be an incredibly expensive endeavor for the Roman Empire, so to try and combat this, Scapula was pressured into pressing immense taxational burdens on the Britons.4 The second unpopular action, and one that directly leads to the support of the Iceni by the Trinovantes tribe, was the founding of a veteran colony at Camulodunum. To reward veterans of the Legion who had served during the conquests of Britain, Scapula gifted them the Trinovantes city of Camulodunum, which greatly angered the surrounding Celtic tribesmen.5 Another cause of the rebellion was the fact that the Iceni and other Britons had likely been preyed upon by money lenders. The most concrete example of this was the forcible lending of 40 million sesterces by Roman philosopher Seneca to the Iceni people under an exorbitant interest rate. The Iceni did not need the loan, as the Roman conquest of Britain had more or less reached its conclusion. So when the debt was called in all at once, the Iceni were unable to pay the loan back and found themselves subjected to harsh Roman measures to reclaim the loan.6 The final straw that pushed the Iceni and their supporters over the edge was the Roman reaction to the death of the Iceni King Prasutagus. Upon his death, King Prasutagus decreed that the Iceni territory would be co-ruled by his two daughters and the Roman Emperor Nero. He hoped that this would protect his family and ease the Iceni into Roman rule. The Roman Procurator of Britain, Catus Decianus, however, was insulted by the will and dispatched a slave force to plunder and loot the Iceni holdings.7 Iceni nobles were stripped of their ancestral titles, and their lands were divided up between the Romans. When King Prasutagus’s wife Queen Boudicca protested against the treatment of her people, she and her daughters were subjected to unspeakable atrocities by the pillaging Romans. After this event, Queen Boudicca rallied her soldiers and prepared to drive the Romans out of Britain.8 However, the Iceni would need to approach the idea of rebellion with caution. The Roman legions in the area were more than capable of routing them while they were in the process of preparing to revolt.9

This opportunity would arise when Paulinus set out campaigning on the Isle of Mona. Accompanying him was the 14th Legion and a detachment of the 20th Legion as well as an assortment of Roman auxilia. So when Boudicca and the Iceni rose in revolt and marched on Camulodunum, Paulinus was not present to take control of the situation and prepare a defense. Instead, Catus Decianus was the one who was turned to organize a defense of Camulodunum. Decianus decided to dispatch a meager force of 200 poorly equipped slaves to supplement the Legionary veterans that had taken up arms to defend their home. A separate detachment of Legionnaires from the 9th Legion led by commander Petilius Cerialis decided to march to the aid of Camilodunum; however, when they neared the Roman settlement, Boudicca and her forces ambushed them while they were marching and utterly destroyed them. Camilodunum was then subjected to absolute destruction, with the slaves and veterans only managing to defend the Temple of Claudius for a handful of days before the Iceni overwhelmed them and slaughtered every man, woman, and child within.10

By this point, Paulinus had received word of the revolt and the atrocities committed at Camilodunum. Luckily, the Isle of Mona had been brought into compliance at this point, so Paulinus was not forced to decide whether or not he needed to abandon his campaign. Instead, he organized the legionaries and auxilia to begin a march back to Londinium, while he prepared a contingent of cavalry to set out with him to reach the settlement first.11 There he hoped to decide whether or not the merchant settlement would make a suitable position from which to make war.10 By this point, unbeknownst to Paulinus, Queen Boudicca had managed to amass a force of around 230,000 warriors, and they were also marching upon Londinium.2 With great haste, Paulinus reached Londinium, where he was met with unfortunate news. Catus Decianus, the one who was in large part responsible for the revolt, and the one responsible for the failure of the defense of Camulodunum, had fled to Gaul when he had received word that Camulodunum had fallen and Boudicca was marching on Londinium with a force of several thousand furious Celtic warriors. Paulinus was now aware of exactly how difficult defeating the Iceni rebellion would be. His army numbered around 10,000 men, the bulk of which were still marching back to Londinium. He was also aware of the defeat of Petilius Cerialis and the 9th Legion due to their haste to meet the rebellious Queen and her army in the field of battle. Thus, he decided to abandon Londinium to its fate and regroup with the rest of his force until he could gather a larger number of troops and choose a suitable location to do battle.10

Consequently, Londinium easily fell into Boudicca’s clutches when she and her force arrived. They committed many of the same atrocities that they committed at Camuldunum. They burned much of the city to the ground and slaughtered whoever had not fled after Paulinus when he departed. Paulinus then began to march up modern-day Watling Street to meet up with the rest of his forces, passing through the settlement of Verulamium, where many more Roman citizens fled behind his wake. Once he reached the rest of his forces, he continued up Watling Street while trying to determine ways to amass a larger force. He knew he could not count on receiving any reinforcements from the routed 9th Legion. But he could implore the veteran 2nd Legion to come to his aid. They were an incredibly potent fighting force and were a mere two days march away. However, the Praetor of the legion, Poenius Postumus, refused to dispatch any of his forces to support Paulinus. By this point, Boudicca had reached Verulamium, and her troops had set about looting and pillaging the settlement and its surrounding area. However, they notably had ignored nearby castella, which, had they seized it, would have provided a large number of supplies to her ever-expanding army. The Britons were running high on victory after this success, as they had destroyed the 9th Legion, and Paulinus had yet to meet them in any kind of open conflict.15 These feelings of imminent victory caused many Celtic warriors to bring their wives and children along for the coming final fight. Both Boudicca and Paulinus knew that he and his forces were the only remaining threat to Iceni dominion over Britain. So, Paulinus continued to try to evade Boudicca for a while longer; however, supplies were growing short, and if he continued to delay, he could face mass desertions or even mutiny.2 Therefore, against his wishes, Paulinus was forced to find an optimal location for the battle. Somewhere his heavy legionaries could utilize all of their strengths and the numerical superiority of the Iceni could be minimized. Thankfully, the Iceni were distracted by potential plunder and had lessened their chase to give him time to decide where to confront them.17 As Paulinus advanced further up Watling Street, he happened upon an unknown location that he deemed suitable to face the coming Iceni horde. It is described as “a narrow defile, closed in at the rear by a forest, having first ascertained that there was not a soldier of the enemy except in his front, where an open plain extended without any danger from ambuscades.”18 This location, with its narrow front, would limit the number of Celts that could engage his forces at a time, allowing his superiorly trained and equipped troops to defeat them. The forest on his rear would also force his men into combat, preventing them from fleeing, forcing his men to either fight or die.3

With the location chosen and the maximum number of troops that he could muster prepared, Paulinus organized his troops for the coming battle. He arrayed them in a standard Roman battleline with the Veteran Legionnaires making up his center. Then he placed the auxilia and cavalry on his left and right flanks with him joining the cavalry force on the right flank. Boudicca and her troops soon approached. They arrayed themselves in a mass of unorganized infantry, armed with little more than a pair of loose woolen trousers and whatever weaponry they could find.3 Queen Boudicca and her daughters rode in front as part of a group of royal chariots. This was the first time Paulinus had actually seen his foe since the rebellion had begun, and Boudicca is described “as more intelligent than usual for women, tall, formidable of face and voice, with long red-blond hair, dressed in a gold torque, a multicolored tunic, and a cloak fastened with a brooch.”21 The Iceni arranged their extensive baggage train in a U-shape along the outer edges of the plain, creating a bowl shape of sorts. Their wives, children, and elders were all brought within wagons that were a part of the baggage train to watch the great warrior queen lead her forces to ultimate victory over the Roman invaders. This is when Boudicca rode up and down her line giving her speech to rally her troops. However, Paulinus had a speech of his own to give to his men:

“Up, fellow-soldiers! Up, Romans! Show these accursed wretches how far we surpass them even in the midst of evil fortune. It would be shameful, indeed, for you to lose ingloriously now what but a short time ago you won by your valour. Many a time, assuredly, have both we ourselves and our fathers, with far fewer numbers than we have at present, conquered far more numerous antagonists. Fear not, then, their numbers or their spirit of rebellion; for their boldness rests on nothing more than headlong rashness unaided by arms or training. Neither fear them because they have burned a couple of cities; for they did not capture them by force nor after a battle, but one was betrayed and the other abandoned to them. Exact from them now, therefore, the proper penalty for these deeds, and let them learn by actual experience the difference between us, whom they have wronged, and themselves.”22

After his speech reached its end, he gave the signal to commence the attack. The Celts approached jovially, singing, shouting, and jeering at the Romans, while the Romans marched silently and in perfect formation. The Iceni Chariots harassed the Legionaries as they approached, but their light armor allowed them to be driven off by Roman archers.23 Then, when the Celtic foot soldiers neared, the Romans drew their Pilum Javelins and hurdled them into the disorganized mass of Iceni. After their pilum were exhausted, they broke into a charge and rushed full speed into the approaching enemy soldiers. The battle quickly escalated into a senseless state of conflict, as the battle lines dissolved and it became a fight for survival, the Romans savagely fought their way forward. After fighting for most of the day, the Roman cavalry managed to pierce through the Celtic flanks, driving them into a full-scale retreat. However, when the Celts turned to flee, they quickly realized that the wagons that had been arrayed behind them had effectively trapped them in. The Roman forces continued to press their advantage, brutally slaughtering the retreating enemy combatants. Then they callously fell upon the women and children at the baggage train and massacred them too. The Legionaries were so consumed by bloodlust that they even slew the various pack animals that the Iceni had brought with them.24

The aftermath of Boudicca’s revolt is a rather timid affair. Boudicca managed to flee the slaughter of her people; however, there are various speculations as to the manner of her death. Cassius Dio believes that she fell ill and died.25 Tacitus believes that she poisoned herself. However, what is known is that any further attempts to resist the Roman occupation of Britain were met with fire and steel from a vengeful Paulinus. Supported by a reinvigorated Roman Legion, strengthened by the arrival of 2,000 Legionaries from Germania. The Praetor of the 2nd Legion Poenius Postumus, upon learning of Paulinus’s unlikely victory, fell upon his sword, knowing that he had denied his legion a piece of the glory and refused several direct orders from his commanding officer.24 Overall, around 70,000 Roman soldiers, merchants, and other civilians had been slain by Boudicca and her army.1 But it is reported that upwards of 80,000 Iceni and other Celts had been slain during the Battle of Watling Street.24 In order to prevent further rebellions, Paulinus enacted a series of harsh policies on the Britons; however, these tactics had little effect and often promoted further rebellion rather than stifling it. The rebelling Britons also suffered immense famine, as in their haste to catch the Romans unaware, they had neglected to plant any crops to harvest for the coming winter. So as the seasons changed, they quickly found themselves in quite a destitute position.29 The new procurator Julius Classicianu worked to undermine Paulinus’s success by advocating for a change in governor by reporting that Paulinus was severely mismanaging Britain. His efforts were likely motivated by his own self-interest, as he was part of the Celtic Nobility through marriage. Therefore, he worked to get Paulinus removed, and subsequently he increased his own power in Britain.30 Rome, after much deliberation, decided to recall Paulinnus and replace him with a man named Petronius Turpilian. Thus ended the British Disaster, an unlikely Roman victory, and a devastating blow to resistance against Roman occupation.31

- Gil Gambash, “To Rule a Ferocious Province: Roman Policy and the Aftermath of the Boudican Revolt,” Britannia 43 (2012): 2-3. ↵

- Dio Cassius and Herbert B. Foster, Dio Cassius: Roman History, Volume VIII, Books 61-70, trans. Earnest Cary (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1925), 97. ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 11. ↵

- L. A. du Toit, “TACITUS AND THE REBELLION OF BOUDICCA,” Acta Classica 20 (1977): 149. ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 10. ↵

- Dio Cassius and Herbert B. Foster, Dio Cassius: Roman History, Volume VIII, Books 61-70, trans. Earnest Cary (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1925), 83-87. ↵

- L. A. du Toit, “TACITUS AND THE REBELLION OF BOUDICCA,” Acta Classica 20 (1977): 149–158, 150-151. ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 10. ↵

- L. A. du Toit, “TACITUS AND THE REBELLION OF BOUDICCA,” Acta Classica 20 (1977): 149–158, 152-153. ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 10-11. ↵

- Dio Cassius and Herbert B. Foster, Dio Cassius: Roman History, Volume VIII, Books 61-70, trans. Earnest Cary (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1925), 95. ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 10-11. ↵

- Dio Cassius and Herbert B. Foster, Dio Cassius: Roman History, Volume VIII, Books 61-70, trans. Earnest Cary (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1925), 97. ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 10-11. ↵

- L. A. du Toit, “TACITUS AND THE REBELLION OF BOUDICCA,” Acta Classica 20 (1977): 149–158, 153-154. ↵

- Dio Cassius and Herbert B. Foster, Dio Cassius: Roman History, Volume VIII, Books 61-70, trans. Earnest Cary (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1925), 97. ↵

- L. A. du Toit, “TACITUS AND THE REBELLION OF BOUDICCA,” Acta Classica 20 (1977): 149–58. 153-154 ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 11. ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 11. ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 11. ↵

- Ann R. Raia, “Boudicca,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), 1. ↵

- Dio Cassius and Herbert B. Foster, Dio Cassius: Roman History, Volume VIII, Books 61-70, trans. Earnest Cary (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1925). 97-99 ↵

- Dio Cassius and Herbert B. Foster, Dio Cassius: Roman History, Volume VIII, Books 61-70, trans. Earnest Cary (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1925), 103. ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 11-12. ↵

- Dio Cassius and Herbert B. Foster, Dio Cassius: Roman History, Volume VIII, Books 61-70, trans. Earnest Cary (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1925), 105. ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 11-12. ↵

- Gil Gambash, “To Rule a Ferocious Province: Roman Policy and the Aftermath of the Boudican Revolt,” Britannia 43 (2012): 2-3. ↵

- Tacitus, Annals of Imperial Rome Book XIV, trans. Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodbribb (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 11-12. ↵

- L. A. du Toit, “TACITUS AND THE REBELLION OF BOUDICCA,” Acta Classica 20 (1977): 149–158, 153-154. ↵

- Gil Gambash, “To Rule a Ferocious Province: Roman Policy and the Aftermath of the Boudican Revolt,” Britannia 43 (2012): 5. ↵

- L. A. du Toit, “TACITUS AND THE REBELLION OF BOUDICCA,” Acta Classica 20 (1977): 149–158, 155-156. ↵

5 comments

Elliot Avigael

After reading this, it’s no wonder the Romans wrote terrifying accounts of the Picts, Britons, and other Celtic peoples–which explains why they refused to hold onto England closer to the fall. Celts and Romans were no friends of each other, and this article highlighted that perfectly.

Aztlan Alvarado

What a great article on a historical figure that doesn’t often get talked about enough. Everyone always hears about how powerful the Romans were but it’s interesting seeing how they begun to panic and were pressured and almost defeated by a band of different tribes all led by a powerful woman in Boudicca, which was seen as rare and not the norm in those times.

Elliot Avigael

I had briefly heard of the Celtic Queen Boudicca some time ago. When it comes to the Mount Rushmore of history’s strongest female military leaders, I think Boudicca deserves a place on it. I really was not well versed in the Roman conflicts with Celtic peoples outside of Julius Caesar and Gaul, so I really enjoyed hearing about an entirely separate battle. This article made me even love the Celts more than I already did; they were able to give the Romans a run for their money several times over, and that’s saying something considering Emperor Hadrian had to build a wall to keep them out.

Carlos Hinojosa

Great article and it did a great job explaining what happened and how it happened. It’s nice reading articles talking about certain events that usually get overshadowed by other events. I like roman history mostly because it involves a lot of fighting and it’s interesting to see powerful empires fall and learn how they fell. This article got straight to the point which I like but also kept me the reader interested the whole time.

Robert G. Salinas Retired History Teacher

Well written with excellent use of voice to engage the reader. The information provided that led up to the final battle and it’s out come was well documented. Great insight was given to this era of European history.