Winner of the Fall 2018 StMU History Media Award for

Best Article in the Category of “United States History”

What, exactly, makes the United States of America so unique? Is it our food, our inventions, our skyscrapers, or our fancy cars? Could the answer to this fundamental question lie within our superb economic system, abundant natural resources, or other environmental factors? No, not a single one of these things make the United States particularly unique. Instead, the key to our uniqueness lies within the name of our nation itself. We are, after all, called the United States of America for an important reason. It was our states alone that birthed, continued, and brought to conclusion exactly what Alexis de Tocqueville once famously called the “Great Experiment.”1

The “Great Experiment” was not created in a day, nor was it created by accident. Rather, it was the natural result of the accumulation of different ideals and values held dear by the occupants of the British colonies. Even as early as 1643, there existed between Connecticut, Plymouth, New Haven, and Massachusetts a “perpetual confederation,” titled the “United Colonies of New England.”2 This particular union was crafted by the four colonies with great care, and guaranteed that the general government of the confederacy would never inter-meddle “with the government of any of the jurisdictions.”3 A shining example of both American spirit and American ideals, the Confederacy would last well over forty years. Even later, Benjamin Franklin would draft the “Albany Plan” in 1754, a plan of union that, although it still described a confederacy, was ultimately considered too centralized for the free American colonies.4

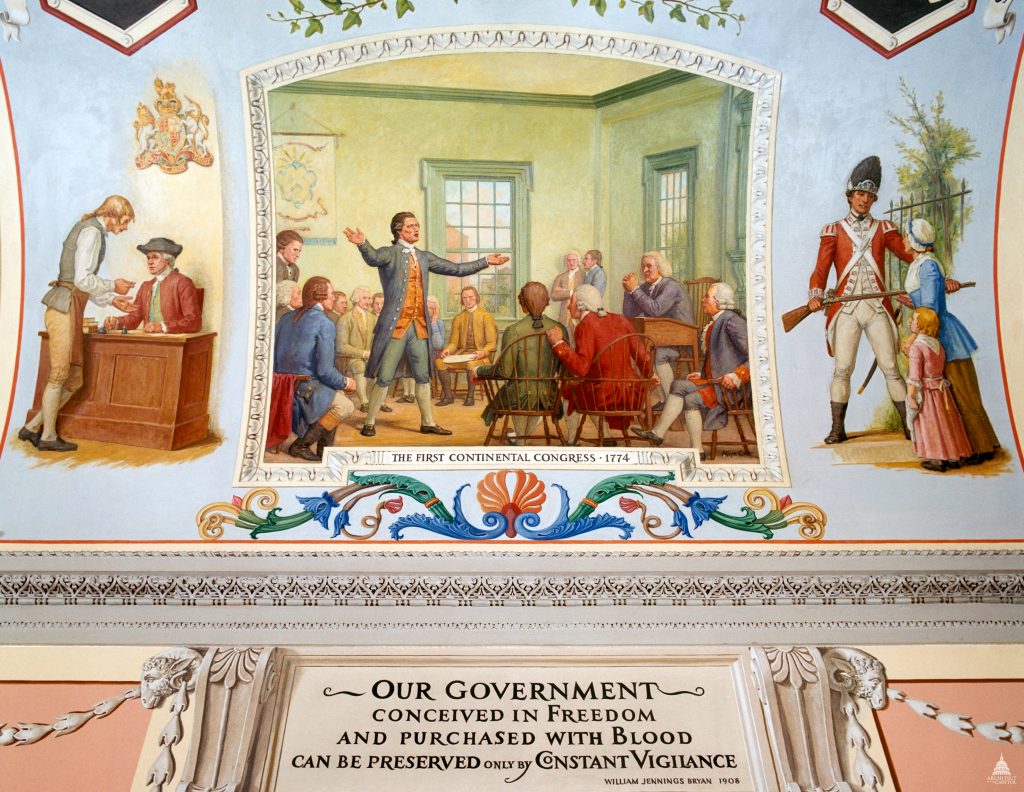

When one truly considers the extensive cultural and societal history of the thirteen colonies, it seems only natural that they would enter into a confederation rather than consent to a consolidated government. They had, after all, already grown accustomed to governing themselves under British rule well before the signing of the Declaration of Independence.5 Indeed, almost all of the colonies had created unique systems of governance within their respective territories long before coming together to ignite the American Revolution in 1775. Two years into the war, the states (as they were then called) realized that they could not continue battling the British as private, competing body politics. Accordingly, their representatives convened in the Second Continental Congress, and, after much debate, drafted and sent out the “Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union” for review by the legislatures of the thirteen independent states. The states were slow to adopt the document, and, as a result of the values entrenched within them, were very hesitant to give up their hard-fought rights to another Federal body. However, by the year 1781, the Articles of Confederation was finally ratified by every single state government. All of the states officially entered into a perpetual union with one another.6

The Articles of Confederation, when closely examined, ultimately reveals the very nature and spirit of the famed American Revolution. A direct product of the Revolution itself, the document was an ode to the “self-government” mentality that the colonists had slowly come to adopt after serving the British Empire for so long. Nowhere is this better examined than in Article II of the document, which reads:

Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every Power, Jurisdiction and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.7

Mirroring the ideas advanced within the old “United Colonies of New England,” this Article provides great insight into the mind of the early American revolutionary. Note, also, the use of the term “expressly delegated” within the piece above—the term was paramount, due in part to the particular construction of the Articles of Confederation. The idea of “expressly delegated” powers is the backbone of any true federalist system, and this fact rang especially true regarding the government created under the Articles of Confederation. Every single statement within the instrument was painstakingly crafted by the Second Continental Congress to leave absolutely nothing open to Federal interpretation.8 By creating a document that was thoroughly rooted in the ideals of “expressly delegated” powers and federalist ideal, the members of the Second Continental Congress were ultimately able to provide the states with a constitution that gave a detailed explanation of the rights they were ceding to the general government by entering into the Confederation. Hence, the document not only effectively prevented the slow, gradual erosion of states rights, but it also rightly defended the states against Federal encroachment into their affairs. Due to its potentially damaging nature, the idea of “expressly delegated” powers is one of the most important and immutable differences observed between the Articles of Confederation and its successor, the American Constitution.

The Articles of Confederation was certainly not without its flaws—it was drafted in the fires of war, and was not nearly as generous to the Federal government as it safely could have been.9 Indeed, the product of the Second Continental Congress could accurately be described as a physical manifestation of the reluctance that the colonies-turned-states held regarding perpetual union. Their fear was certainly understandable, however, as they had each just broken away from Great Britain, and were only beginning to enjoy their hard-earned independence. In their newfound freedom, the states were especially wary about ceding their self-governance to a foreign head by creating a miniature “Great Britain” within some federal entity identical to their previous masters in everything but location. In remedying this great fear, they went to great lengths to remove the Federal government of even the most fundamental powers needed for its existence. The flaws that had been sowed throughout the Articles of Confederation were never to be remedied, however, and despite receiving a great amount of local and international praise, the Articles would not stand the test of time.10

Abandoning the Articles of Confederation was in no way an easy or quick process. In fact, the states had never originally intended to replace the Articles in the first place. Instead, they had originally called for a convention to “devise such further provisions as shall appear to them [members of the convention] necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.”11 That is, the Confederacy had ordered the creation of a convention that would specifically draft amendments to the Articles, which were to be later examined by the general Congress for subsequent approval or rejection. The government did not, in any way, consent to or endorse the creation of a new form of government altogether. Little did the Confederacy know, however, that the convention would nevertheless betray the Union and do exactly that.

Upon arriving in Philadelphia, the various delegates would quickly enter into secrecy. No longer officially representing their states, the men in the convention were acting illegally, attempting to undermine the very product and cause of revolution. The room in which they illegally drafted their new constitution was to be boarded up, and discussion about the new document kept to an absolute minimum.12 Luckily for the delegates, attendance of the convention was remarkably small. Of the seventy-four men assigned to the convention, nineteen would never even attend a single session. Of the fifty-five that did, only thirty would actually stay for the entirety of the convention. As if that fact alone wasn’t bad enough, only six of the fifty-six men who signed the Declaration of Independence were present at the convention.13 Thus, we observe a very strange phenomenon: 30 to 39 individuals, many of whom were avid defenders of centralized government, acting alone, drafting a document in complete secrecy, almost without any political resistance whatsoever. The convention was filled to the brim with Federalists of all kinds, almost completely free from any true defenders of the Articles of Confederation or the ideas that spawned it. For the Federalists, there could not have been a better time to draft a new constitution, as Thomas Jefferson was serving as an ambassador in France at the time, and Patrick Henry had “smelled a rat in Philadelphia,” and subsequently refused to participate in the destruction of the Confederacy.14 Despite the lack of any real resistance, the Convention would still find itself divided over the issue of state representation within the new government. Some members argued for a return to the representation that the Articles of Confederation had provided, while others argued for representation based on population alone. The members were eventually able to come together in agreement on the issue, creating the famed “Great Compromise.” Even this “Great Compromise,” however, would ultimately fail to balance the proposed government, changing nothing but the physical structure of Congress while avoiding altogether the express powers of government around it.

After five grueling months, on September 17, 1787, the convention finally put the finishing touches upon their magnum opus—the American Constitution. Our founding fathers had spent a significant amount of time preparing the document for public approval, in order to give the document the appearance that it desperately needed to gain public support.15 Elbridge Gerry, a significant delegate in the convention, did not even turn heads when he stated that “the people should appoint one branch of the government in order to inspire them with the necessary confidence…”16 Immediately following the appearance of the Constitution, many were skeptical of its true intentions, going so far as to propose that the members of the convention had carefully drafted the contract as to give it only the appearance of a document that respected the ideals of self-governance, while hiding altogether its real purpose. The belief that the 30-39 authors of the Constitution actually held opposing interests to those of the states is mirrored in many papers published shortly after its release. A popular article at the time remarked:

Their aim, I perceive, is now to destroy that liberty which you set up as a reward for the blood and treasure you expended in the pursuit of and establishment of it. They well know that open force will not succeed at this time, and have chosen a safer method, by offering you a plan of a new Federal Government, contrived with great art, and shared with obscurity, and recommended to you to adopt; which if you do, their scheme is completed, the yoke is fixed on your necks, and you will be undone, perhaps for ever, and your boast liberty is but a sound, Farewell!17

Regardless of origin, the Constitution had finally become available to the general public. Much to our founding fathers’ dismay, however, the unveiling of the document was met with immediate and almost unshakable controversy. Indeed, it took only eight days after the boarded windows were removed from the convention for the first published Anti-Federalist paper to appear.18 The paper, titled “A Dangerous Plan Of Benefit Only to The Aristocratick Combination,” immediately sparked a debate that would later lead to the creation of both the Bill of Rights and our modern political parties.19

The Federalists were not content with staying silent, and their published response to the first Anti-Federalist paper marked the beginning of a ravenous three-year-long debate that would constantly pit intellectual titans against each other in the public forum. If you lived in New York during the ratification process of the Constitution, it would not be uncommon for you to pick up a newspaper and find Alexander Hamilton and James Madison going against Patrick Henry and George Clinton on the front page. Every paper was published anonymously, which allowed almost anyone with an opinion and a knack for writing to join in on the grandiose debate. Not everyone, however, would be responded to. One of the most popular Anti-Federalists, a writer known only by his pen-name “Brutus,” for instance, published over six groundbreaking essays that never once received a proper Federalist response.20

In the beginning, the two political “parties” were fairly evenly matched. As the public debate dragged on, however, the Anti-Federalist party began to crack.21 The unrest within the Anti-Federalist faction arose when a collection of amendments was first proposed by the Federalists as a sign of compromise. This idea of compromise would ironically grow to be the very thing that tore the entire Anti-Federalist faction apart. Half were content with the adoption and application of certain amendments to the Constitution, and the other half kept true with the original intent of the party: the rejection of the proposed Constitution altogether.22 The Federalists were quick to jump on the opportunity to divide their opponents, and promised to adopt certain (edited) Anti-Federalist amendments if the various states were to accept the proposed Constitution. In this way, the state governments became distracted, and the divide between the Anti-Federalists became even greater. Even more, the proponents of the old Articles of Confederation began to focus upon creating amendments rather than resisting the adoption of the document altogether. With their opposition all but shattered, the Federalists were eventually able to get the Constitution ratified by a majority of the states by June 21, 1788.23 The Articles of Confederation, and all of the ideas behind it, had almost officially been dissolved. The original ideals of the American colonists, of “expressly delegated” powers and state sovereignty, it seemed, were destined to be diluted and lost within a new government that would grow to eventually control and oversee (either directly or indirectly) every minute action taken by the states.

Although the Constitution had been generally adopted by the respective states, there still existed a great number of independent state legislatures that were not eager to invest their hard-earned freedom and self-governance into a government that could so easily turn against them.24 A majority of the states, while certainly eager to adopt a new constitution to remedy the downtrodden state of the Union, refused to part with a specific number of liberties that they had enjoyed under the Articles of Confederation. Thus, the creation of an official movement calling for a Bill of Rights was born. Of the amendments proposed to be added to the Bill of Rights, one stood out among the others. This particular amendment sought to prevent the expansion of Federal power by reviving the Second Article within the Articles of Confederation and applying it to the Constitution. If adopted, this amendment would effectively nullify the idea of “implied powers” within the Constitution, and render anything not “expressly delegated” to the Federal government once again open to the states—it would safely ensure the continuance of “expressed powers,” and preserve federalism indefinitely within the union. The amendment was the tenth item added into the proposed Bill of Rights, and many Anti-Federalists believed that it had the potential to remedy every problem that they observed within the proposed government.

Due to its overwhelming popularity, James Madison feared that the Constitution would fail to be successfully adopted if the tenth amendment were not added, and quickly promised to adapt it for use in the Constitution.25 Madison, however, feared that reviving the core of the Articles of Confederation and applying it to the new government would prove too great a check on centralized power, and secretly had no intention of letting such an amendment defeat what he saw as a necessary purpose of the Federal government.26 Instead, he elected to trick the state legislatures into adopting the Constitution without actually changing the nature of the government by editing the tenth amendment as to effectively render it useless. To Madison, this was the only alternative to simply dropping the amendment altogether, an act that he had grown fairly accustomed to. After all, the “Father of the Constitution” had, up to this point, already culled over 200 proposed amendments that, in his eyes, went to “endanger the beauty of the Government.”27 To find out just how James Madison effectively hollowed out the tenth amendment, it first becomes necessary to carefully observe the construction of the amendment itself. Madison edited the amendment to read, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”28 Upon first glance, this looks strikingly similar to Article II of the Articles of Confederation. However, the facade falls away when the reader considers just what “not delegated… by the Constitution” actually entails. In short, the fundamental flaw in the amendment is brought about as a result of the particularly vague language in which the Constitution was written.29 Between the “necessary and proper” clause buried within the contract and the all-encompassing concept of Judicial Review, there is nothing “not delegated… by the Constitution,” because the referred document provides the Federal government with the means to define and expand its own role in the Union. Proud Federalist Alexander Hamilton even went so far as to boast that this construction was an improvement over the Articles of Confederation, admitting:

The authority of the proposed Supreme Court of the United States, which is to be a separate and independent body, will be superior to that of the legislature. The power of construing the laws according to the SPIRIT of the Constitution, will enable that court to mould them into whatever shape it may think proper.30

Pushed on one side by constant fears of societal unrest and on the other by a strong Federalist movement, the state legislatures would eventually accept Madison’s edited version of the tenth amendment. The subsequent final adoption and utilization of this new and edited American Constitution would, unbeknownst to the states, eventually allow Federal power to extend to all matters save those expressly prohibited by the instrument, effectively bringing an end to the once famed “Great Experiment.”

Over time, as the Anti-Federalist argument faded into obscurity, the newly-adopted Federal government began removing any restriction that was placed upon it by the states. This gradual process began with a famous Supreme Court case: Marbury V. Madison. The intricate details of the case itself are wholly insignificant when compared to the Court’s decision, as it was the decision of the Court that spawned the potentially dangerous idea of what is now commonly referred to as “Judicial Review.” From that day forward, the Supreme Court wielded a power over the states that was not expressly delegated in the Constitution.31 By adopting the doctrine of “Judicial Review,” the Supreme Court jump-started the process of growing out of its original constitutional boundaries by becoming a creator of policy, rather than a mere reviewer of it.32 The Federal government’s utilization of the subjective “spirit” of the Constitution and the seemingly endless variety of vague terms planted within it as tools against the various interests of the states has permitted the institution to reach a level of autonomy that the original colonists could have only dreamed of. This statement is little more than fact: there is not today a single decision made by the state courts, nor is there a single piece of legislature, that can exist without the Supreme Court’s direct or indirect consent.33

The conflict between the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution is fundamental.34 At their core, the many differences between both documents originate within the way each empowered confederal or federal head interacts with the states. Under the Articles of Confederation, the confederal government existed to serve the body politics that created it. Each and every member of the Confederacy received an equal vote, reserved the right to resume all delegated powers, and was protected from the overreaching, negative power of consolidated government via a collection of Articles that respected the meaning of “expressly delegated” powers. Under the Constitution, however, the states exist to serve the federal government. Today, each and every “member” of our modern Union is denied a gross majority of the rights that they once enjoyed so briefly under the Articles of Confederation. One of the many examples of this regretful reality is the fact that our states no longer possess the fundamental ability to directly elect representatives that should serve their interests within the Federal government.35 Indeed, the states cannot even exist without the direct monetary assistance and political support of an overreaching and bloated federal government far bigger than anything conceivable by the original colonists.36 This is the tragic and necessary result of adopting a constitution that not only fails to fully respect the significance of “expressly delegated” or “implied” powers, but one that also provides a branch of the federal government with the sovereign ability to change the “spirit of the constitution” and define its own limits on a whim.37

The Constitution, far from embodying the original ideals of the American Revolution, tragically disregards the principles that created the Declaration of Independence. For better or worse, the contract led to a contradiction of the ideals behind the original “Great Experiment,” and a bloody civil war within 100 years of its adoption. If the American patriots of old where to catch a glimpse of the existing condition of the United States of America, they would certainly find it almost unrecognizable. Perhaps, in reviewing modern-day American politics, they would find themselves in the middle of a nation perfectly described by George Bryan or John Smilie on October 27, 1787:

It is beyond a doubt that the new federal constitution, if adopted, will in a great measure destroy, if it does not totally annihilate, the separate governments of the several states. We shall, in effect, become one great republic. Every measure of any importance will be continental.38

The American Constitution has, regardless of the original intent of any of its various creators, ultimately brought about the creation of a single consolidated Republic consisting of fifty administrative zones, i.e. states. The members of Congress today have little obligation to serve anything but a vague notion of “the people,” an obligation that they can exploit to no foreseeable end.39 Tragically, the once proud and powerful states, the very backbone of the American Revolution, have today been transformed into weakened shadows of their former image, required to carry out endless mandates forced upon them by an ever-expanding Federal government. The previously stark line separating the states and the government that they serve has been so blurred as to render the two almost completely inseparable.40 It may be little exaggeration to claim that the states are today under the same amount of restriction that they had once endured under Great Britain. For one, the states can no longer directly elect members to serve as their representatives in Congress. For another, they are constantly forced to pay taxes to a Federal body that, again, does not necessarily represent their individual interest. They are, in almost every sense of the term, often forced to participate in “taxation without representation,” one of the main issues that once stirred the original American colonies to revolution.41 In the end, the American Constitution not only subverted the ends of the “Great Experiment,” but it also indirectly contributed to the tragic undoing of the very ideas that ignited the American Revolution itself.

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (London: Saunders and Otley, 1835), 15. ↵

- Douglas G. Smith, “An Analysis of Two Federal Structures: The Articles of Confederation and the Constitution,” San Diego Law Review 34, no. 1 (1997): 259. ↵

- John F. Manley and Kenneth M. Dolbeare, The Case Against The Constitution: From the Anti-Federalists to the Present (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1987), 8. ↵

- John F. Manley and Kenneth M. Dolbeare, The Case Against The Constitution: From the Anti-Federalists to the Present (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1987), 8. ↵

- Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (MA: Courier Corporation, 2010), 74. ↵

- Merrill Jensen, The Articles of Confederation: An Interpretation of the Social-constitutional History of the American Revolution, 1774-1781 (WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1940), 120. ↵

- Second Continental Congress, Articles of Confederation (1777) University Study Edition (San Bernardino: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013), 8. ↵

- Andrew C. McLaughlin, The Foundations of American Constitutionalism (New York: The New York University Press, 1932), 147-148. ↵

- Andrew C. McLaughlin, The Confederation and the Constitution, 1783-1789 (New York: Collier, Later Printing edition, 1967), 49. ↵

- George William Van Cleve, We Have Not a Government: The Articles of Confederation and the Road to the Constitution (IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 1-3. ↵

- Second Continental Congress, Documents Illustrative of the Formation of the Union of the American States: Proceedings of commissioners to remedy defects of the Federal Government, September 11th, 1786 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1927), 1. ↵

- John F. Manley and Kenneth M. Dolbeare, The Case Against The Constitution: From the Anti-Federalists to the Present (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1987), 12. ↵

- John Joseph Lalor, Cyclopaedia of Political Science, Political Economy, and of the Political History of the United States by the best American and European Authors (New York: Maynard, Merrill, & Co., 1899), 231. ↵

- Joseph L. Daly, “Interpreting the Constitution: Stability v. Needs,” Capital University Law Review 16, no. 2 (1986): 214. ↵

- John F. Manley and Kenneth M. Dolbeare, The Case Against The Constitution: From the Anti-Federalists to the Present (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1987), 14. ↵

- Jonathan Elliot, The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution as Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia, in 1787, Vol V. (Berkeley: University of California, 1888), 160. ↵

- John Jay, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Patrick Henry, Brutus, The Complete Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers (San Bernardino: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018), 595-596. ↵

- John Jay, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Patrick Henry, Brutus, The Complete Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers (San Bernardino: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018), 459. ↵

- John H. Aldrich, Why Parties?: The Origin and Transformation of Political Parties in America (IL: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 84. ↵

- John Jay, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Patrick Henry, Brutus, The Complete Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers (San Bernardino: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018), 568. ↵

- David J. Siemers, Ratifying the Republic: Antifederalists and Federalists in Constitutional Time (CA: Stanford University Press, 2004), 1-2. ↵

- David J. Siemers, Ratifying the Republic: Antifederalists and Federalists in Constitutional Time (CA: Stanford University Press, 2004), 208-211. ↵

- Bernard Grofman, Donald A. Wittman, The Federalist Papers and the Institutionalism (NY: Algora Publishing, 1989), 222. ↵

- David J. Siemers, Ratifying the Republic: Antifederalists and Federalists in Constitutional Time (CA: Stanford University Press, 2004), 25. ↵

- David J. Siemers, Ratifying the Republic: Antifederalists and Federalists in Constitutional Time (CA: Stanford University Press, 2004), 209. ↵

- U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Amendments to the Constitution, Annals 1:761, 767–68 (IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2000). ↵

- James Madison, Speech Proposing the Bill of Rights (D.C.: Cong. Register I, 1789), 437. ↵

- Terry Jordan, The U.S. Constitution and Fascinating Facts About it (IL: Oak Hill Publishing Company, 2017), 47. ↵

- Saikrishna B. Prakash and John C. Yoo, “The Origins of Judicial Review,” The University of Chicago Law Review 70, no. 3 (2003): 887-888. ↵

- John Jay, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Patrick Henry, Brutus, The Complete Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers (San Bernardino: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018), 419. ↵

- David J. Siemers, Ratifying the Republic: Antifederalists and Federalists in Constitutional Time (CA: Stanford University Press, 2004), 209-210. ↵

- Gordon S. Wood, “The Origins of Judicial Review Revisited, or How the Marshall Court Made More out of Less,” Washington and Lee Law Review 56, no. 3 (1999): 787-789. ↵

- Gordon S. Wood, “The Origins of Judicial Review Revisited, or How the Marshall Court Made More out of Less,” Washington and Lee Law Review 56, no. 3 (1999): 787. ↵

- Andrew C. McLaughlin, The Foundations of American Constitutionalism (New York: The New York University Press, 1932), 146-148. ↵

- G. Haynes, The Senate of the United States (NY: Henry Holk, 1938), 79-117. ↵

- John Jay, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Patrick Henry, Brutus, The Complete Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers (San Bernardino: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018), 517. ↵

- John Jay, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Patrick Henry, Brutus, The Complete Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers (San Bernardino: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018), 419. ↵

- John Jay, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Patrick Henry, Brutus, The Complete Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers (San Bernardino: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018), 517. ↵

- G. Haynes, The Senate of the United States (NY: Henry Holk, 1938), 79-81. ↵

- John F. Manley and Kenneth M. Dolbeare, The Case Against The Constitution: From the Anti-Federalists to the Present (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1987), 26-27. ↵

- Peter Force, Volume 5 of American Archives: Consisting of a Collection of Authentick Records, State Papers, Debates, and Letters and Other Notices of Publick Affairs, the Whole Forming a Documentary History of the Origin and Progress of the North American Colonies; of the Causes and Accomplishment of the American Revolution; and of the Constitution of Government for the United States, to the Final Ratification Thereof (NH: National Library of the Netherlands, 1837), 700. ↵

102 comments

Kelly Guadalupe Arevalo

Congratulations on your award! It was an amazing article. I believe that the whole idea of no taxation without representation works in its whole only theoretically; at least if we stick with that idea as written. By following that statement, theoretically, a person could “decide” they do not share the interests of their community and declare themselves (and/or the land they live in) a sovereign nation, and therefore are not obliged to pay taxes or accept the laws that may be imposed on their neighbors. But that is an absurd extreme. So, I liked how you presented this idea in the context of the time and explain clearly how it contradicts the original ideals of the states. Good job!

Vianey Centeno

This article had a lot of curiosity. I discovered a lot of new information that I was unaware of before and am happy to have it. I am aware that a lot of work went into creating the constitution, but reading this has helped me appreciate all of it even more. It’s highly intriguing to consider the other viewpoint as frequently as possible.

Daniel Gimena

Interesting article, with a very different point of view of the American Constitution.

The author gives arguments to support his opinion that the American Constitution does not support the very nature and spirit of the American Revolution. The north-American colonies started the Revolution against the British crown because they wanted their own sovereignty, setting their own rules for the self-government of their State. The author’s point is that the final Constitution does not reflect those initial rights that the Revolution had fought for, stating a more Federalist government, which reminded more to the British system that the Americans had fought against, and wanted to avoid at all cost.

It is always interesting to read different points of view and opinions, and the manner in which the author develops his is very professional and based on deep research which, at least, makes the reader doubt and rethink what his or her initial thoughts.

Travis Green

What an interesting and thought provoking point about how the principles upon which the constitution was built on has been essentially betrayed more and more over the years. I had no idea that making the constitution was as difficult as it seems to have been. This was a very well researched and well written article that made me think because I never would have looked at the constitution this way if it weren’t for this article. You really get a sense of the turmoil of that time from this article.

Daniela Iniguez-Jaco

First off congratulations on receiving an award, and second off this was an amazing article! I found it interesting how the nation was divided between the Articles of Confederation and The constitution based on the political parties. I remember reading about the Great Compromise in our textbook, and reading this article has cleared things up for me as well.

Seth Roen

I thought this was a great article about the United States’ early years, well, the Article of Confederation. And I thought it was it was a nice tough that you mentioned that the great debate of the country’s destiny continues even to this day. It does make you wonder what would have happened if the American Confederation succeeded, or if states had a greater allowance of autonomy.

Amelie Rivas-Berlanga

Congratulations on getting the best “United States” article award! This article is super descriptive. It goes into every corner of the details and explains everything so well. It is interesting to read that the Constitution did not have the people’s support. It is understandable because they did not want to be ruled like in Britain. Having both sides perspective on things makes things so much clearer.

Matthew Gallardo

This article was, to say the least, one very impressive read. the Article was easy to follow and read, with a good timeline from the ideal that the articles were the idea for the average revolutionary’s mind, to the convention, to the 3 year debate between federalist and nonfederalist papers, to the conclusion which states that the states and their people are under the same abuse it once was with great Britain. with the ending comment, I couldnt agree more that the people are no longer represented. instead, it is a handful elites in the media, congress, and executive branch as well as the judicial who use the 2 party lock to gain power for themselves

Elliot Avigael

It’s amazing that the debate over the federal government’s role in every day political decisions is still being debated to this day. I really don’t think either alternative was right or wrong, whether it was the Articles or the Constitution. As a newly birthed country, it was indicated that we would need to experiment with certain systems of power to figure out which one is right for us.

You do pose an interesting and complicated question, and I will admit that it’s quite strange that such a convention would be held in great secrecy, and limited to only a select few. I’m a big believer that the Constitution is only a positive if its tenets are followed to the letter. If its standards are abused and ignored, it is irrelevant.

The Great Experiment didn’t fail, America IS the Great Experiment. In every generation we are constantly reforming and trying to figure out how to better our country.

Trenton Boudreaux

I had never thought to look at the constitution in this way before. I suppose it is true that the constitution effectively betrayed the ideals of the revolution to a certain extent, as the states are no longer independent countries, but provinces. A very well researched and well written article highlighting the troublesome first years of the existence of the United States of America.