Winner of the Fall 2018 StMU History Media Award for

Best Descriptive Article

The echo of her name still resonates in the hearts of Argentinians and others inspired by her. In life and in death, she was the vivid fire and image of revolution that was never extinguished. Born as Eva María Duarte, married to Juan Domingo Perón, she was the woman named by the people as Evita.

During the 1940s, Argentina experienced pivotal political changes that provoked a long battle of political struggles. Opposing ideologies—left and right—on the two forces of the political spectrum clashed. The left’s party gained momentum since they advocated equality, which appealed to most of the Argentinian population. Juan Domingo Perón was the man on the left who promised Argentina access to education, health care, and women’s rights, just to name a few.1 However, it was his wife, Eva Perón, who moved masses and won Argentina’s heart and trust. Through Peronism, the political movement that promoted social justice and equality, the thinking of many Argentinians started changing.

In 1946, Eva Perón became the First Lady of Argentina, and it was then that her popularity started growing. Not many knew much about the actress who married the future president of the nation, but soon enough, she would become one of the most notorious figures of Argentina. She revolutionized the role of a First Lady, by defying societal conventions. Unlike other women who had held her position, Evita played a humanitarian role. She tirelessly worked with the poor, the working class, and women. The Eva Perón foundation, administered by herself, provided financial assistance to hundreds of people every day. Her work consisted of the creation of schools, health care, and rights for the working class.2 Eva Perón was named Argentina’s spiritual leader. During Perón’s second term as president, the people demanded that Evita run for vice president. The opposing parties despised her for her great popularity and her humanitarian works.3

And so, Evita ran for vice president of Argentina. During her campaign, however, she was diagnosed with uterine cancer. However, she was not told the fatal diagnosis of her illness at the time. Today, scientists know that Evita developed uterine cancer because Juan Perón was a carrier of Human Papillomavirus (HPV). Everyone witnessed the slow deterioration of her body but never of her spirit. The predictions were that Evita and Perón were both going to win by a considerable margin. Unfortunately, she had to withdraw from the election because she was continually growing weaker. On her death bed, Evita voted for the first time, because this was the first election in which women were able to vote, and partly because of her influence in obtaining voting rights for women in Argentina.4 Nurses who looked after Eva described her to be in incredible pain during her last days. Sometimes she would spend a whole day sedated with morphine.

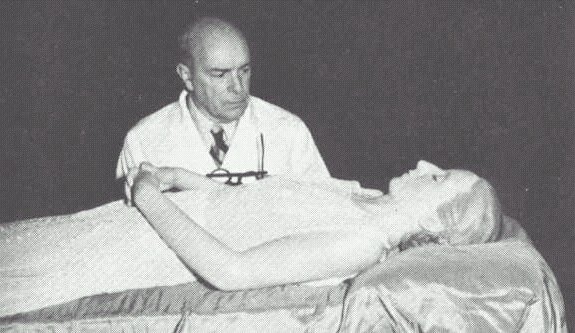

On the morning of July 26, 1952, it was announced to the Argentinian nation that the “abanderada de los humildes y enfermos” had passed away.5 It took twenty-five years and a long journey for her remains to be finally buried. Argentina started its eternal mourn. Before Eva’s passing, Perón hired Dr. Pedro Ara, the man who would immortalize her remains.6 He was a young doctor popular for his impeccable work at embalming. Perón demanded that he complete his work at the headquarters of the CGT (Confederación General del Trabajo de la República Argentina). Dr. Ara prepared Evita’s corpse for the long funeral that was to come. A lot of people were expected to attend; however, the number of people that came to mourn Evita was impressive. It is estimated that two million Argentinians came to see her. For sixteen days and nights, multitudes visited their first lady. The pope received 160,000 petitions to make her a saint.7 Argentina and Chile ran out of flowers because of how many offerings were brought to her. The funeral had to be suspended because Dr. Pedro Ara was afraid that if it took too long, he might not be able to finish the embalmment of her corpse.

Dr. Pedro Ara was very talented at his job. He had a “secret” formula to preserve bodies impeccably. For an entire year, he embalmed and preserved Evita’s corpse. She was his greatest masterpiece. The goal was not only to preserve, but to immortalize her remains as if she were living. Some described her looking like a doll or as herself but not dead, just in a profound sleep. Dr. Ara wrote El Caso Eva Perón, a book describing the meticulous work done to preserve her remains. He would inject into her system everyday his “secret” formula.

As Dr. Ara worked to preserve Evita, Perón’s popularity started to decline. The opposing parties took advantage of Evita’s absence. Many attempts were made that tried to remove Perón from power. Finally, in September of 1955, Juan Domingo Perón was removed from power by the Liberation Revolution, led by Pedro Eugenio Aramburu. With Aramburu’s regime, which lasted three years, everything that had to do with Juan Domingo Perón and Eva Perón was banned. Because of that, Perón was sent into exile.8

By then, Dr. Ara had already finished his work and had left Evita in perfect condition, as if she were still alive. However, her corpse was still at the CGT. This was a problem because the rivalry between Perónists and Anti-Perónists was turning more violent. Perónists were trying to steal Evita’s corpse, while the government threatened to throw the corpse into the sea.9 The ruling government was unsure where Evita’s body was. When they found the corpse at the CGT, they had to perform a series of tests to determine whether it really was her, not because of the normal decay a body undergoes, but because of the perfect state the corpse was in. A piece of her ear was removed along with a finger in order to determine if the doll-like corpse was indeed her. In the process, they discovered that Evita had undergone a lobotomy. There is no evidence that supports that Evita was aware of this, let alone that she had consented to the procedure. The government finally took possession of the CGT and Evita’s corpse. The whereabouts of her corpse remained extremely confidential. It was unknown to Argentinians if she was even still in the country. The government was concerned that the presence of her corpse might ignite a revolution.10

On November 22, 1955, Evita’s corpse was assigned a guardian, Colonel Carlos Eugenio de Moori Koenig. His duty was to protect the corpse and keep it hidden from revolutionaries. These, however, were not the instructions he decided to follow. It is argued that he stole the corpse from the CGT and took her to his private office. There, Moori kept Evita as a trophy. Often, he invited guests and showed them that she was in his possession. More disturbing than his garish display of Evita’s corpse were the sexual acts Moori Koenig engaged in with Eva Perón’s corpse. Rumors said that Moori Koenig was infatuated with Eva during her lifetime and that he had developed a sick obsession with her while having custody of her corpse. Fortunately, this information reached high ranking officers. When the government found out about his behavior, Moori Koenig was immediately discharged from his position and Evita was taken away from him. Everywhere Moori Koenig had secretly taken the corpse, roses and offerings were left for Evita. This made him believe that he was being followed.11

A new guardian was assigned to the remains of Eva Perón. Colonel Hector Cabanillas was the man who took the responsibility and mission of caring for Eva Perón’s corpse. This mission was of great importance because the slightest mention of her existence resulted in revolts and a threat to the political situation of Argentina. It was decided that it would be best if Evita was buried secretly. Colonel Cabanillas was the one who elaborated the logistics of this operation. At first, the plan was to bury her under a pseudonym in Argentina. Everything was going according to the plan. During the night a man, whose name is unknown, was supposed to bury her. However, he fell asleep while waiting for everyone at the cemetery to leave. While asleep, Evita’s corpse was mysteriously stolen. Even more strange, the body was shortly recovered but there is no evidence of how12.

In April of 1967, the plan at last had success. This operation was a lot more complex and took months of planning. Eva Perón’s corpse was taken to Milan, Italy. There, she was buried under the pseudonym of Maria Maggi de Magistris, an Italian widow. Even the people who despised her recognized her courage and strength as a woman. When buried in Milan, she was buried standing up. That was how Eva Perón lived her life, as a woman who would never bow down for anything she didn’t believe in, and as someone who would stand up for the weak and ill.13

Fourteen years of dictatorships and weak democracies had governed Argentina. The lack of political structure and stability made Evita even more popular. They wanted the “reina de los descamisados” to be back home. The place of her grave was a mystery to them. Many wondered whether she was ever buried at all. Eventually, the revolts became so acute that Aramburu was threatened. Although there is still speculation around the details surrounding his death, on June 1, 1970, Pedro Eugenio Aramburu was murdered. The main theory consists of him being kidnapped and murdered as part of a demand for the return Perón, and for Evita’s corpse. The pressure Perónists exerted produced fruit on September 1, 1971, when Evita was exhumed from her grave in Italy and transported to Madrid, were Juan Perón was living in exile. In the process of her exhumation, the workers involved were astonished to find a woman buried years ago in perfect condition. Dr. Pedro Ara was invited to inspect the corpse to determine if the corpse was indeed her. He confirmed that the woman buried as Maria Maggie de Magistris was Eva Maria Perón, and that she was in the exact perfect condition he had left her in 1953. Nonetheless, her family disagreed with this statement. They described how her feet, nose, ears, and fingers were damaged, most likely because of all the moving and corruption. Her feet were said to be damaged because of being buried on her feet.14

Perón was at last in custody of his beloved Evita. At this point, he already had another wife, Maria Martinez. She had admired Evita and the work she had done in her lifetime. For Maria, it was an honor to be in her presence. Every day, she would kindly brush through Evita’s blonde hair.15

Someone else in Perón’s house was infatuated by Evita: Jose Lopez Reja. He, like Moori Koenig, engaged in sexual acts with Evita’s remains. This time, Perón’s wife joined him. There is no evidence that indicates whether Perón was aware of this behavior or not.

With Aramburu dead and Evita’s whereabouts now known to Argentinians, Perón was able to return from exile. He came back to Argentina and started his third presidency in May of 1973. It came as a surprise to Argentinians that Perón didn’t bring Evita’s remains with him.16 Enraged, Montoneros, a group of radical Perónists, stole Aramburu’s remains from his grave. Their objective was to exchange Aramburu’s remains for Evita’s. When Perón died in 1974, his third wife, Maria Martinez, finally brought Evita’s remains back to Argentina. Once again, Evita was mourned for several days by Argentina, but this time she was beside her husband. Perón and Evita were united once again when buried at the presidential residence, Los Olivos. This was supposed to be temporary, because the Altar de la Patria was being constructed by Maria Martinez. However, she was removed from power in 1976 by Jorge Rafael Videla, resulting in the projected mausoleum never to be finished.17

In 1976, Evita and Perón were divided one more time. She was taken away and buried in the Duarte’s family mausoleum.18 This would be the last time Eva Perón’s remains would be moved. Since then, she has been safe two-hundred meters below the ground, with her family. Eva’s grave is a site for Argentina and tourists around the world to visit. Her life, her legacy, and certainly the story of her death was immortalized.

- Eva Peron, In My Own Words: Evita (Buenos Aires: New Press, 2005), 91. ↵

- Eva Peron, In My Own Words: Evita (Buenos Aires: New Press, 2005), 18. ↵

- Eva Peron, In My Own Words: Evita (Buenos Aires: New Press, 2005), 19. ↵

- Eva Peron, In My Own Words: Evita (Buenos Aires: New Press, 2005), 14. ↵

- Eva Peron, In My Own Words: Evita (Buenos Aires: New Press, 2005), 16. ↵

- John Barnes, Evita, First Lady: A Biography Of Eva Perón (Indiana: Grove Press,1996), 162. ↵

- John Barnes, Evita, First Lady: A Biography Of Eva Perón (Indiana: Grove Press,1996), 167. ↵

- Margaret Schwartz, Dead Matter: The Meaning of Iconic Corpses (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 41. ↵

- John Barnes, Evita, First Lady: A Biography Of Eva Perón (Indiana: Grove Press,1996), 90-122. ↵

- Margaret Schwartz, Dead Matter: The Meaning of Iconic Corpses (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 45. ↵

- Margaret Schwartz, Dead Matter: The Meaning of Iconic Corpses (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 47. ↵

- John Barnes, Evita, First Lady: A Biography Of Eva Perón (Indiana: Grove Press,1996), 175 ↵

- John Barnes, Evita, First Lady: A Biography Of Eva Perón (Indiana: Grove Press,1996), 177. ↵

- Margaret Schwartz, Dead Matter: The Meaning of Iconic Corpses (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 40. ↵

- Margaret Schwartz, Dead Matter: The Meaning of Iconic Corpses (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 43. ↵

- John Barnes, Evita, First Lady: A Biography Of Eva Perón (Indiana: Grove Press,1996), 179. ↵

- Margaret Schwartz, Dead Matter: The Meaning of Iconic Corpses (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 42. ↵

- John Barnes, Evita, First Lady: A Biography Of Eva Perón (Indiana: Grove Press,1996), 167. ↵

151 comments

Montserrat Moreno Ramirez

It was a good article, It was great to know how much the people really cared about a government public figure. In most latin american countries most people despises the government and are not used to making this gestures when they pass away. I think that having a female model that really cared for the working class is something to admire and to look up to. Amazing how the pope received so many prayers for her to become a saint.

Micaela Cruz

I had only heard of Eva Peron briefly in one of my spanish classes during high school. At first, I thought this article was going to be the general life story of Eva but the article went beyond that and exceeded my initial expectations. I greatly appreciate how the author went into a deeper history of the events that took place after her death, events that are not often spoken of. It was disturbing to hear about the sexual acts done to her corpse, it is truly sickening. Despite that, it was amazing to read about how admired Eva was by the Argentinian people. A great article!

Christopher Vasquez

This article was well-written. I had no idea how influential Eva María Duarte, Evita, was to the people of Argentina. She seemed like a true role model and a great inspiration to anyone from any nation. It’s unfortunate that she met an untimely end due to HPV; however, her legacy lives on: she helped her husband with his education and health care reforms, as well as played a major role in women being able to vote. Eva Peron was truly an amazing person.

Alexandra Rodriguez

I love reading about powerful and inspirational women throughout history around the globe. I truly shows the diversity of international gender beliefs. However it saddens me that the Peronists continuously attempted to steal and ultimately disrespect the corpse. The disrespect done to the corpse by those disturbed individuals for their own pleasure is horrifying. Her illness was what prevented her from her political goals and that is a shame, but her memory will definitely live on.

Adrian Cook

This was definitely an interesting article on Eva and what she did for the Argentinian communities. Personally, no matter how much I’m in influenced by a politician, I would never want to preserve their body. I would much rather visit a grave site rather than look at a dead body in doll looking form. What she did for Argentina and the citizens was amazing because she was such a great lady, it just sucks she had to pass so soon right before elections.

Engelbert Madrid

I never heard about Eva Peron and her passion to help the poor Argentinian communities. It is sad to know that her dream of becoming vice president was not going happen due to her illness. However, her political movement towards social justice and equality made her become an important leader for the Argentinian people. She was charismatic and supportive to anyone that was facing inequality at the time; therefore, it’s important to recognize her. I’m glad that the author of this article wrote this to inform readers about different leaders in other countries.

Daniela Duran

This was an impressive article! Congratulations Marina! I really enjoyed reading about Evita’s life, but it was specially shocking to find out how much difficulty her corpse went through. I cannot believe that so many people were interested in having her dead body, and it was simply terrifying to think that some of them even had sexual activity with her! Certainly, however, it is impressive how her body was preserved in such a good condition, but I wonder if it was because of this that so many people took advantage of her corpse? Perhaps if she had simply been buried, none of this would have happened. I really enjoyed reading the article! I loved the title, the structure and even the images were great!

Christopher Hohman

Nice article. Evita Peron sounds like she was an incredible woman. She did so much for the poor and the ill too. I do not know if there has ever been a first lady of the United States that has ever been so popular. What I find remarkable is that, after her death, she was preserved so well, that there was very little change in her appearance after all she went through. I am glad that she is now buried in peace with her family, she deserves to rest in peace

Enrique Segovia

Good article. I think the title fits the article perfectly, since indeed, Evita’s corpse kept on being moved around many places and dealt with by many. I particularly enjoyed that Evita, while on her death bed, was enabled to vote, as she was the one who promoted women’s rights (which included female suffrage); for this, it is satisfying that she was able to enjoy one of the rights that she fought for. Also, I was impressed that Evita’s body was moved around so much, and that even after her death, everyone knew she would cause great controversy. She was loved by the Argentinian people, and she deserves honor for all that she did.

Karina Cardona Ruiz

I had briefly heard about Eva Perón and how loved she was by the Argentinian people in one of my history classes. However, I did not know that she had been embalmed nor that her corpse had been desecrated and moved around so much. It’s sad to think that Eva was loved by so many for the way she treated others yet she was treated like an object and not as having been the person she was after her death. It was nice of the Argentinian people to attend Eva’s funeral and shower her in flowers but the Perónists just took it too far by trying to steal the corpse repeatedly. I can’t believe Moori Koenig abused his position of power by using Evita’s corpse for his own sick pleasure and entertainment. I also found the fact that once Eva’s corpse had been in Perón’s custody, his wife was brushing her hair everyday and that Jose Lopez Reja was engaging in sexual acts with the corpse alongside Perón’s wife incredibly disturbing. At least Evita was finally put to rest in 1976. Job well done on writing your article!