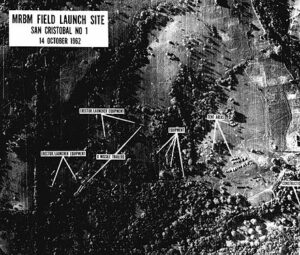

On October 14, 1962, Major Richard Heyser was on a flight path selected by CIA analysts over western Cuba flying a U-2 spy plane. However, Heyser discovered something quite shocking. Heyser took 928 pictures on the path that captured a nuclear missile construction site at San Cristobal, Pinar del Rio Province.1

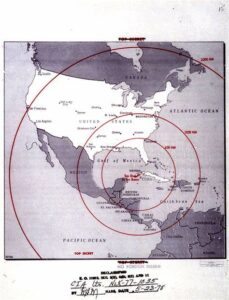

Two days later, on October 16, President Kennedy was busy reading the morning newspaper when his National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy revealed to Kennedy photographic evidence of surface-to-surface medium-range ballistic missiles, or MRBMs, in Cuba that were being installed by the Soviet Union. A shocked Kennedy responded to the news by saying, “He can’t do that to me!”2 Kennedy immediately called together the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, who then discussed the details of the missiles and how to approach the crisis. Art Lundahl, director of the National Photographic Interpretation Center, briefed the council that these were the same missiles as the ones seen in the recent Mayday parade on Moscow’s Red Square, which allowed them to confirm that these were nuclear missiles.3 The missile system was the SS-4 sandal, which had a range of 1300 nautical miles, meaning that the southern states and Washington DC were at risk. The missiles were capable of explosions from 200 to 700 kilotons, making them thirty-five times more powerful than the nuke dropped on Hiroshima.

With the stakes this high, the committee agreed that they needed a response that would avoid nuclear war. The Committee had a split decision on two options: they could launch an airstrike on the missile sites, followed by an invasion without them seeing it coming, or they could create a naval blockade. Both decisions had flaws, with an airstrike and invasion creating the risk of the Soviets launching any missiles the US might miss; and a naval blockade would degrade any future surprise attacks and could still create the risk of the Soviets launching missiles.4 The majority of the committee sided with the decision to launch an airstrike and follow-up invasion, including General Maxwell Taylor, Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Dean Rusk, Secretary of State. One of the big reasons many supported the airstrike and invasion was that they were focused on making up for their failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion. Dean Rusk also included that the Soviet Union had a desire to grow in power and wouldn’t take the naval blockade well, for a naval blockade was considered an act of war. Much stress was on Kennedy’s mind as he was the one making the decision. The committee agreed to move forward with mobilizing military airstrikes, setting the US military readiness to DEFCON 3 so as to be ready when a decision was made.5

The US had not always been enemies with the Soviet Union. In fact, the US and Soviet Union had been allies during WWII, but their relationship changed after the US bombed Hiroshima as a way of demonstrating the power the US had developed. This resulted in the Cold War occurring where the US and Soviet Union competed over power. On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched the first satellite creating the space race. The US also believed that Russia had nuclear technology. As a result, the US sent ICBM nuclear missiles to NATO allies where they were deployed in England, Italy, and Turkey.6

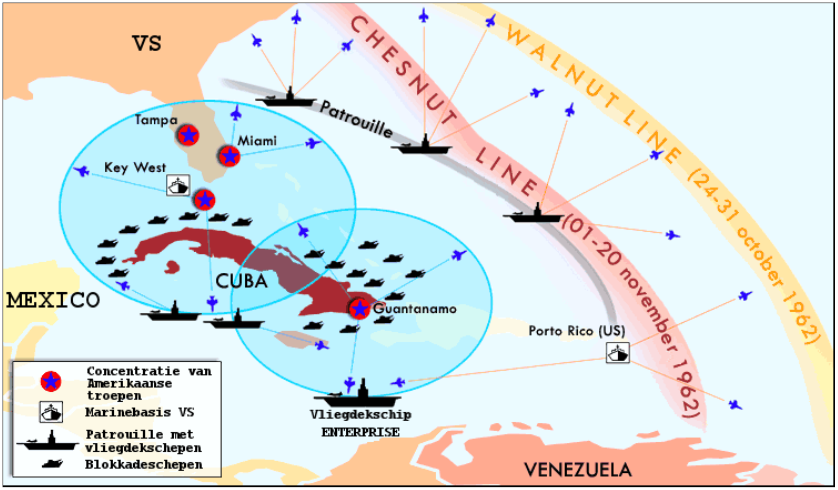

On October 18, the US counted forty missiles being installed in Cuba, and these missiles could hit every place in the country except Seattle. The Executive national security believed that if the US military launched a missile strike, the Soviet Union would continue to deliver missiles to Cuba. Professor Menkel Meadows stated, “It is always easier to escalate than it is to deescalate a situation.”7 JFK had to prevent hostile interaction, meaning he needed to give the Soviets a chance to back down before taking action. Executive Committee of the National Security Council decided to create a naval blockade on Soviet ships and call the action a quarantine, because a naval blockade was considered an act of war. Executive Committee of the National Security Council also sent nonencrypted communications to military bases to have the US be prepared for retaliation from the Soviets. With this strategy of creating a blockade, the US became more flexible with its next choices of action: an airstrike or an invasion.7

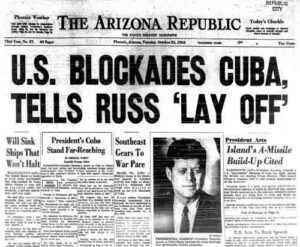

The New York Times learned about the news and planned to report on the story on October 19. This forced Kennedy to request that the New York Times hold off on releasing the story. Instead, Kennedy insisted he would inform the country himself for the safety of the country. On that Monday evening, October 22, Kennedy addressed the American people about the crisis. He stated that the US had obtained evidence of Soviet missiles being placed in Cuba. These nuclear missiles gave the Soviet Union nuclear strike capabilities on the Western Hemisphere, meaning that the missiles were capable of reaching most cities in the US, Mexico, and South America. Kennedy stated that the US response to the crisis was to create a naval quarantine that would begin on Wednesday, October 24, which would prevent any Soviet ships with military equipment from reaching Cuba. Finally, Kennedy stated that “We will not prematurely or unnecessarily risk the costs of worldwide nuclear war in which even the fruits of victory would be ashes in our mouth.”9

Under the authority given by the Constitution and endorsed by Congress, President Kennedy took six initial steps toward this crisis. The first step was a quarantine on all ships heading to Cuba, effective on October 24, no matter what nation these ships might come from. If any military equipment were to be found on these ships, they would be forced to turn back; however, it was to be made clear that the United States was not denying any necessities of life to Cuba, as the Soviets had done with the Berlin blockade of 1948. Step two was to keep the US military prepared and keep Cuba under surveillance watching for any military buildup; and if a build-up got to a level too severe, retaliation would become justified. Step three was to proclaim that any nation in the Western hemisphere that was attacked by the Soviet Union would be considered an attack on the United States. In step four, Kennedy stated that the US military base at Guantanamo, located at the Southeastern tip of Cuba, would be reinforced and put on standby. In step five, Kennedy called for a meeting of the Organization of American States (OAS) to consider this crisis a threat to hemispheric security. Step six called for a confrontation with the Soviet Union in the Security Council of the United Nations to demand that the Soviets dismantle and withdraw all military weapons in Cuba before the quarantine could be lifted. In the final step, Kennedy called upon Khrushchev to withdraw from this attempt at world domination, which was a threat to world peace, for the US had no wish for war with the Soviet Union.10

Khrushchev became outraged with Kennedy, knowing that the US would not allow nuclear weapons to be set up in Cuba. Khrushchev wrote a letter in response to Kennedy on October 23, following Kennedy’s letter and speech. The letter stated that the US actions were a threat to peace and a violation of the United Nations charter. The US actions in international waters were considered an act of aggression leading the world to nuclear war. Khrushchev believed that Kennedy had to learn to deal with the missiles in Cuba, just as the Soviet Union dealt with the missiles in Turkey and Italy. With this reasoning, the Soviet Union concluded that the missiles were only for defense.11

Khrushchev vowed that Soviet ships would continue on track to Cuba, and if stopped by the US Navy, they would be forced to retaliate. The US tracked ships heading towards Cuba and the closest ships would arrive at the quarantine line by October 24, the day the quarantine was to go into effect. This brought much stress upon not just the US but to the world itself, as confrontation became inevitable and the US could only hope that the Soviet Union would honor the quarantine. October 24 was the scariest day of the crisis, where the world stood still.12

On that morning on October 24, nineteen Soviet ships were identified heading towards Cuba. Three of the vessels, however, were close to the quarantine line. It was reported that one of the three ships was a submarine that had positioned itself between the other two Soviet ships. After hearing about the submarine, Kennedy authorized the USS Essex aircraft carrier to respond with retaliatory force if needed. However, before striking, they noticed that the ships slowed down, allowing Kennedy to pull back on the strike. The ships turned around and nuclear warfare was avoided that day. However, the crisis wasn’t over, and America now went to Def Con 2 for the first time in history, one level away from nuclear warfare.13

The events that led to this faceoff on October 24 all started with the Cuban Revolution that occurred when Cuba was ruled by a corrupt dictator, General Batista, who was overthrown in 1959 by Fidel Castro and his forces. Castro sought to end political corruption and take control of many Cuban industries, among them several American-owned businesses, meaning the nationalization of foreign-owned properties. Castro blamed the United States for Cuba’s economic misery. Castro came out as a communist eight months after the revolution, and then began to build closer ties with the Soviet regime in order to seek protection from the US. This resulted in the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1962.14 The Bay of Pigs invasion was an unsuccessful attack launched by the CIA where Cuban exiles trained and funded by the US government were sent to Cuba to overthrow the government. It is believed that the biggest contributions to the failure of the attack were poor planning, failure to provide air support for the rebels, and Cuba hearing about Cuban exile training camps that had allowed them to prepare for the invasion, and the arrest of many of the opponents in Cuba wanting to join the attack allowing Castro’s forces to outnumber the exiles.15

On the morning of October 26, Kennedy came to the conclusion that the only way to solve the issue of the crisis was to proceed with an invasion of Cuba. They prepared for this by setting up military invasion plans and devise plans for setting up a new government in Cuba, replacing Castro. At this point, America’s only hope was that the invasion wouldn’t end in failure like the Bay of Pigs invasion. However, at six that evening, they received a letter from Khrushchev proposing that the missiles in Cuba would be dismantled if the US did not invade Cuba. Furthermore, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy held a private meeting with Dobrynin, the Soviet Ambassador, and discussed the option of removing the missiles in Turkey, and in return, the Soviet Union would remove the missiles in Cuba. The next morning, on October 27, Khrushchev sent another letter where he took back the pledge of a noninvasion, and instead required the removal of missiles in Turkey. The US finally had a lead that could end this crisis; however, they were certain that their allies in Turkey would not be happy with the removal of US missiles. The Kennedy Administration still had much to decide.16

The situation became more severe when later that day, on October 27, a spy plane piloted by Major Roudolph Anderson was shot down by a Soviet missile in Cuba. Kennedy decided not to retaliate. On the same day, a nuclear-armed Soviet submarine was hit by a small depth charge from a US Navy vessel, signaling it to come up. Two of the commanders on the submarine ordered the launch of a torpedo. One of the commanders, however, rejected this order resulting in the world being saved. The stakes were becoming too high and Kennedy needed to make a decision fast. President Kennedy finally came to a proposal. Robert F. Kennedy would be sent to discuss the proposal with Soviet Dobrynin. After negotiation, they came to the conclusion that the US would remove its missiles in Turkey, and in return, the Soviet Union would remove its missiles in Cuba. On October 28, Khrushchev stated that all missiles in Cuba would be dismantled and removed. The US did the same in removing the missiles in Turkey. The crisis was averted and the world would see another day.17

- Jonathan Colman, The Cuban Missile Crisis : Origins, Course and Aftermath (Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 69. ↵

- Alice George, The Cuban Missile Crisis: The Threshold of Nuclear War (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Taylor & Francis Group, 2013), 46. ↵

- Sheldon M. Stern, The Week the World Stood Still : Inside the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis, Stanford Nuclear Age Series (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2005), 39. ↵

- Alice George, The Cuban Missile Crisis: The Threshold of Nuclear War (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Taylor & Francis Group, 2013), 49. ↵

- Sheldon M. Stern, The Week the World Stood Still : Inside the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis, Stanford Nuclear Age Series (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2005), 40-45. ↵

- Sheldon M. Stern, The Week the World Stood Still : Inside the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis, Stanford Nuclear Age Series (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2005), 12-14. ↵

- Edward A. Danielyan, “Cuban Missile Crisis: How Thirteen Days Changed the World Note,” UC Irvine Law Review 9, no. 4 (2019 2018): 994. ↵

- Edward A. Danielyan, “Cuban Missile Crisis: How Thirteen Days Changed the World Note,” UC Irvine Law Review 9, no. 4 (2019 2018): 994. ↵

- Richard C. Hanes, Sharon M. Hanes, and Lawrence W. Baker, eds., “Kennedy, John F,” in Cold War Reference Library, vol. 5, Primary Sources (Detroit, MI: UXL, 2004), 244–247. ↵

- Richard C. Hanes, Sharon M. Hanes, and Lawrence W. Baker, eds., “Kennedy, John F,” in Cold War Reference Library, vol. 5, Primary Sources (Detroit, MI: UXL, 2004), 247-248. ↵

- James G. Blight and Janet M. Lang, The Armageddon Letters : Kennedy, Khrushchev, Castro in the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012), 73-75. ↵

- Richard C. Hanes, Sharon M. Hanes, and Lawrence W. Baker, eds., “Kennedy, John F,” in Cold War Reference Library, vol. 5, Primary Sources (Detroit, MI: UXL, 2004), 249-250. ↵

- William A. Darity Jr., ed., “Cuban Missile Crisis,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2008), 2. ↵

- Michael Powelson, “The Cuban Revolution: An Overview,” in The Cuban Revolution, ed. Myra Immell (Detroit, MI: Greenhaven Press, 2013), 13–22. ↵

- Flannery Burke and Tad Szulc, “Bay of Pigs Invasion,” in Dictionary of American History, ed. Stanley I. Kutler, 3rd ed., vol. 1 (New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2003), 430-431. ↵

- William A. Darity Jr., ed., “Cuban Missile Crisis,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2008), 184. ↵

- William A. Darity Jr., ed., “Cuban Missile Crisis,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2008), 184-185. ↵

12 comments

Maria Fernanda Guerrero

Great article! You were able to deliver a detailed account of the Cuban Missile Crisis so vividly capturing the tense moments and high stakes involved during the Cold War. The leadership and diplomacy displayed by President Kennedy and his administration showcased the importance of rational decision-making in times of international tension. Your articles also provide valuable insight into the complexities of global politics and balance of power during that chaotic period. Great work in highlighting this pivotal moment in history!

Carina Martinez

This is such an interesting read and a very well-written article! You did a great job on showing the importance of the Cold War. It was interesting to see how the Soviet Union and the US were at first allies to competitors. So great to know, good job!

Vianna Villarreal

Great article! it demonstrates a great way in emphasizing the historical importance of the Cold War. How is it that the US and the Soviet Union have become in a way enemies when they were allies in critical moments? It’s very interesting to see how politics works across countries and the importance of development in crucial moments. Such as when it comes to nuclear weapons and the possibilities of nuclear war. Very interesting article I enjoyed the topic and it was a great way to captivate the reader. The introduction is a great way to capture the reader through suspense.

Martin Martinez

It’s a bit unsettling that we were so close to war but avoided it ever so slimly. Those that are not keenly aware of Soviet-U.S. relations, like myself, don’t really think about these sorts of things, but now most of us can consider ourselves lucky. It’s also baffling to consider in retrospect that, beyond proxy wars, this was probably the closest we ever got to fighting the USSR directly.

A'marie Pollard

The events that occurred on 1962, notably Major Richard Heyser’s aerial reconnaissance and President Kennedy’s response exemplify the critical role of international law and treaties the importance in averting chaos and conflict. Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis showed the necessity of upholding agreements like the United Nations Charter to preserve global peace and security. Thanks for making this informative article !

Fernando Milian

The topic of the missile crisis is a well-studied topic in International Relations classes, not only because it demonstrates the fragility of peace during the Cold War and how diplomacy and negotiation can avoid nuclear conflicts but also because of how it highlights the importance of communication and perception in international politics. I found it fascinating the idea that “it is always easier to escalate than it is to deescalate a situation,” reflecting the inherent challenges in reversing a course of action once tensions have escalated. It is fascinating to see the careful way in which President Kennedy managed the situation to prevent escalation and promote the resolution of the conflict. This is a well-written article that reflects the tensions of those days. However, for those who want to revisit this story in a different format, I recommend the movie Thirteen Days (2000), which goes about how President Kennedy struggled to contain the crisis.

Lauren Sahadi

This article showcased the tension and decision making process during the Cuban Missile Crisis. It really painted a picture of how complex the situation was and the negotiations that led to a resolution. The author did a really great job using his words to portray a very interesting story that readers are drawn into while also giving important information about an event. Great job on this article.

Nicole Estrada

The article skillfully presents the Cuban Missile Crisis as a watershed point in Cold War history, emphasizing its high stakes and the reduction in tensions between Russia and America. Visuals complement the narrative, notably the startling image of Soviet ships approaching Cuba, emphasizing the country’s closeness to the United States. It’s an engaging topic that keeps readers interested with fascinating facts and enticing pictures. Overall, the article offers a thorough and informative examination of this significant historical event. Personally, I can appreciate an article discussing this topic I knew a little about but not much. Great Work!

Esmeralda Gomez

This article highlights the importance and the factors during an incredibly stressful time in American history. We still see the aftereffects of the Cold War now, which just goes to show the significance of this event in places such as Latin America. I really enjoy this topic and its connection to one of the classes I’m currently taking this semester. Amazing!

Jonathan Flores

I really like this article for a couple reason. First, my bias towards important historical events will always be a catalyst to enjoy these such articles. With the Cuban Missile Crisis, I think you expertly developed the idea of the impending doom of the situation that makes this event so substantial in history. With the idea of Mutually Assured Destruction in mind, I think your article does a great job at encapsulating the tone of the event. Second, I appreciated how deeply analytical this article is and how it does not have extreme bias or sentiment that abandons the theme of the message. Great job.