What is In-Vitro Fertilization?

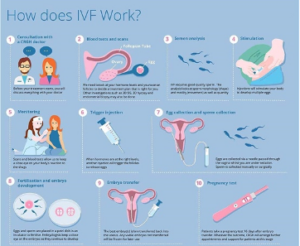

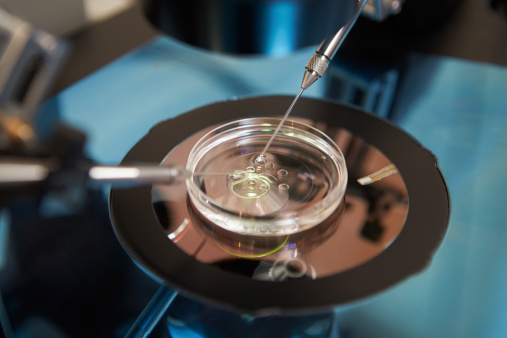

The process by which humans naturally reproduce results in a viable embryo to develop through a gestation period of about 38 – 40 weeks. In-vitro fertilization pertains to scientific reproduction which creates an embryo for couples wishing to conceive who may suffer from medical reproductive challenges for various reasonings including fertility issues and genetic abnormalities limiting natural reproduction. In-vitro fertilization is the process of uniting an egg and sperm outside of the human body in a cell culture. The eggs are removed via a needle to suction out the eggs one at a time under a general medication to ease pain. The sperm used is collected via a sperm sample of the participating party. The sperm is then high-speed washed and spin-cycled in a laboratory to find the healthiest sperm. The cell culture fertilization starts with intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) to create a viable embryo within a few hours. Once the embryo is viable in the culture, the embryo is artificially inseminated into the uterus via a catheter. Multiple embryos are placed into the uterus during one in-vitro insemination session in order to increase the probability of the implantation being successful.

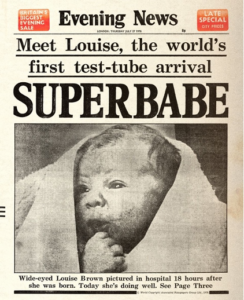

In 1887, researcher Samuel Leopold Schenk first attempted embryo transfer on rabbits and guinea pigs with no success.2 The ethics of sex selection and family balancing. The first successful report of a fertilized human ovum occurred by John Rock and Miriam Merkin, but in-vitro fertilization did not gain fame until July 25th, 1978 when Louise Brown was born via in-vitro fertilization.

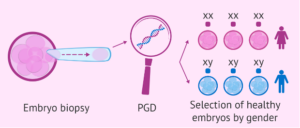

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) was first used in 1989 “to identify and deselect genetically abnormal embryos prior to implantation, thus providing parents who are at high risk of producing children with genetic abnormalities with another option besides the often troublesome experience of in-utero diagnosis and abortion or, alternatively, the birth of a genetically abnormal child.”3 This screening process allows for the success of implanted embryos to increase from 40-50% to 60-70%.4

Gender Selection in In-Vitro Fertilization

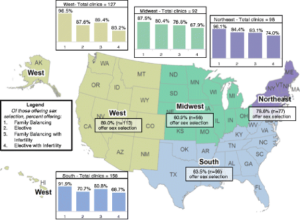

Gender selection during the in-vitro fertilization process occurs pre-implantation, after the embryos are properly assessed for viability in the laboratory. After the PGD is completed, the gender of the embryos is identified based on the embryo carrying two X chromosomes (female) or one X and one Y chromosome (male). There are different state regulations associated with gender selection during the in-vitro fertilization process, along with clinics offering the procedure.

The procedure of gender selection during the embryotic stage of in-vitro fertilization is controversial throughout the United States, along with around the world due to the serious ethical concerns associated with the procedure.

The ethical concerns of gender selection during the embryotic stage of in-vitro fertilization directly relates to morality and religious concerns, associated risks, societal impacts, and the future of embryos not selected during gender selection.

Morality and Religious Concerns Regarding Gender Selection

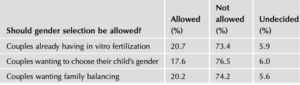

The disapproval rate of social gender selection by in-vitro fertilization is currently 68%, as seen in an American survey taken in 2002.7 The community survey by Morgan Gallup Polls conducted on the attitudes regarding the use of gender selection during in-vitro fertilization in Australia is seen below.7

In the Jewish religion, a man must have at least two children, one male and one female, in order to fulfill the religious requirements which may impact the view on gender selection within the culture. Islam supports the practice of in-vitro fertilization as determined by the International Islamic Center for Population Studies and Research at Al-Azhar University in Egypt in November 2000. This is due to the need for a male heir to preserve the financial and social security of the family. Different schisms of Christianity support infertility treatments but oppose gender selection.10

The Roman Catholic Church’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith issued a statement opposing all methods of artificial reproduction in 1987 due to the beliefs of conception via a conjugal act.7 Currently, the Catholic Church remains firm on their views regarding in-vitro fertilization and gender selection by supporting the following statement originally found in the Donum Vitae (Gift of Life) issued by the Congregation for Doctrine of the Faith during the Catechism of the Catholic Church on February 22, 1987, “The Gospel shows that physical sterility is not an absolute evil. Spouses who still suffer from infertility after exhausting legitimate medical procedures should unite themselves with the Lord’s Cross, the source of all spiritual fecundity. They can give expression to their generosity by adopting abandoned children or performing demanding services for others”.12

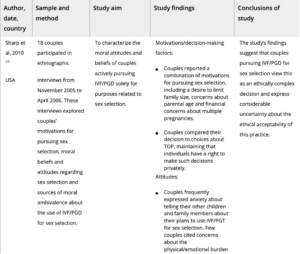

Religious affiliations generally do not support gender selection due to raising the question of the value of one life over the other and if “playing God” is morally just. The moral attitudes and beliefs of couples actively pursuing IVF/PGD solely for purposes related to sex selection is seen in the table below.13

Associated Risks Post-Gender Selection

Zaid Kilani’s “Pregnancy Outcome of Transferred Cycles” study conducted involved 468 cycles resulted in 141 embryo transferred cancellations with 63.1% (89) cancelling due to unwanted gender embryos.15 This study raises the question of the residual mental health impacts the mother endures post selection or cancellation of particular embryos. The process of in-vitro fertilization can result in induced stress and anxiety, especially in terms of gender selection. The mother going through the in-vitro fertilization process consumes multiple hormone medications to stimulate ovulation which leads to complications including mood swings, anxiety and possibly ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). The use of preimplantation genetic disorder (PGD) shows a positive correlation with preterm labor, C-section, and low birth weights of infants selected.16 The possible long-term ethical risks to the offspring of gender selection during in-vitro fertilization used for non-medical reasons have not yet been identified.

Societal Impacts

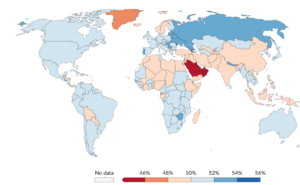

A popular argument suggests that “sex selection may be an expression of sexual prejudice, in particular against girls.”7 Gender selection during the embryotic stage of in-vitro fertilization may lead to a skew of sex ratios that reinforce societal oppression of females throughout different societies already predisposed to the bias. That brings into question the future population ratios and how it could impact the balance of societies, economies and family dynamics worldwide. The prevalence of an unwanted gender imbalance could possibly be amplified due to sex selection and gender preference, along with it being “considered a sexual discrimination and prejudice.”18

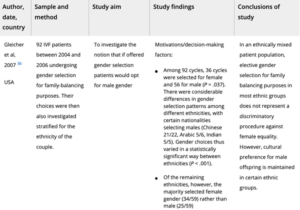

Gleicher’s study (2007) regarding the phycological aspects of gender selection listed in the above table shows how there is a considerable deficit when choosing one gender over the other during the selection period preimplantation.14 Depending on the religious affiliation, societal norms, cultures, and demographic of the population being studied, one may conclude that a specific gender may be selected over another. This has the possibility of shifting society as a whole. The same study also found that 94.1% of the 192 couples undergoing PGD between 2004 and 2008 in Lebanon selected a male embryo. The results of the small survey only show a fraction of the world’s population, leading to the ethical concern regarding other countries’ views on a preferred sex.21 If so, the social demographic regarding the balance of sexes could be severely impacted. This impact could have a ripple effect on the daily lives of individuals, societies, gender roles, occupations, marriage rates, and reproduction rates.

Future of Non-Selected Embryos During Gender Selection

The viable embryos that remain after the gender selection process pose ethical concerns in regards to when life begins, disposal/destruction of embryos, and use of embryos within the scientific community. Religious views differ from scientific views on when life begins. A study by Kato and Sleeboom-Faulkner (2011) conducted in 2009 reported that about 78% of participants saw embryos as life. Kato and Sleeboom-Faulkner (2011) report that in Japan stored embryos are referred to as “lost children” and decisions are made with reference to what participants believe would “satisfy” their embryos.23 This ideology may lead to postponing disposal decisions regarding surplus embryos. The surplus embryos are commonly disposed post-IVF journey, which in a pro-life viewpoint is abortion. The unselected embryos solely due to their gender are destroyed and never given a chance at true life. A smaller percentage of surplus embryos are donated to science to be experimented on in the pursuit of scientific advances. The ethical concern regarding the scientific experimentation on the surplus embryos is whether the viable embryo can feel pain and is considered to be alive. In another study by Kato and Sleeboom-Faulkner (2011) “participants regarded themselves as ‘mothers’ and embryos as their children who ‘had not yet taken on the shape of a human being’”.23 The table below shows a representative list response regarding surplus embryo disposal and the services involved.25

As seen by the data results in Table 4, one can conclude that the ethical concerns regarding the disposal of surplus embryos coincides with the ethical concerns of gender selection. From a total of 615 patients “50.6% chose to discard embryos, 45.4% donated to research, and 4.1% chose reproductive donation.”27 The possible future lives of the embryos not selected due to their gender could significantly contribute to the statistics involving the disposal of perfectly viable embryos.

Conclusion

The ethical concerns regarding the topic of gender selection during the embryotic stages of in-vitro fertilization are prevalent in today’s society when focusing on the advances of biomedical technology. The ethical concerns revolve around various aspects of life, such as religious beliefs and morals. The religious beliefs of an individual put forth ethical concerns regarding when life begins, along with following the particular religious traditions associated with reproduction and fertility. Associated risks of gender selection during in-vitro fertilization involve mental health risks for the mother and the offspring conceived via gender selection. Although there have been no conclusive studies showing the long term effects of gender selection during in-vitro fertilization, it is plausible that there could be negative implications associated with the selection. The ethical societal impacts greatly concern the functionality of societies as a whole due to the possibility of imbalanced ratios of males vs females within a society due to the use of gender selection. The future of embryos not selected during gender selection raises the final ethical concern due to the disposal of “life” in regards to certain religious affiliations and moral perspectives on the human rights of an embryo. The ethical concerns associated with gender selection during the embryotic stage of in-vitro fertilization pose imminent threats to societies, economies, cultures, population gender balance and religious affiliations.

- Whitener, Olivia. “The Ethics of Gender Selection.” SSRC The Immanent Frame. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://tif.ssrc.org/2020/07/31/the-ethics-of-gender-selection/. ↵

- Macklin R. In Seminars in reproductive medicine. New York, Beijing: © Thieme Medical Publishers; 2010. ↵

- Lin, Xinxin, Marta Barranquero Gómez, Julio Martín, Álvaro Martínez Moro, and Zaira Salvador. “Process of PGD for Gender Selection.” inviTRA, June 8, 2017. https://www.invitra.com/en/preimplantation-genetic-diagnosis-pgd/process-of-pgd-for-gender-selection/ ↵

- “Controversies in Gender Selection.” International Congress Series 1271 (September 1, 2004): 345–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ics.2004.05.126. ↵

- Lin, Xinxin, Marta Barranquero Gómez, Julio Martín, Álvaro Martínez Moro, and Zaira Salvador. “Process of PGD for Gender Selection.” inviTRA, June 8, 2017. https://www.invitra.com/en/preimplantation-genetic-diagnosis-pgd/process-of-pgd-for-gender-selection/ ↵

- Capelouto, S. M., Archer, S. R., Morris, J. R., Kawwass, J. F., & Hipp, H. S. (2018). Sex selection for non-medical indications: a survey of current pre-implantation genetic screening practices among U.S. ART clinics. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics, 35(3), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-017-1076-2 ↵

- “Elective Gender Selection of Human Embryos during IVF: Ethical and Public Policy Considerations.” In Human Embryos and Preimplantation Genetic Technologies, 29–34. Academic Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816468-6.00004-7. ↵

- “Elective Gender Selection of Human Embryos during IVF: Ethical and Public Policy Considerations.” In Human Embryos and Preimplantation Genetic Technologies, 29–34. Academic Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816468-6.00004-7. ↵

- Attitudes of respondents from 2002 survey of 650 Australians regarding gender selection ↵

- “Controversies in Gender Selection.” International Congress Series 1271 (September 1, 2004): 345–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ics.2004.05.126. ↵

- “Elective Gender Selection of Human Embryos during IVF: Ethical and Public Policy Considerations.” In Human Embryos and Preimplantation Genetic Technologies, 29–34. Academic Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816468-6.00004-7. ↵

- Ratzinger, Joseph, Alberto Bovone, Pope John Paul II, Pope John Paul VI, Pope Pius XII, and Pope John XXIII. “INSTRUCTION ON RESPECT FOR HUMAN LIFE IN ITS ORIGIN AND ON THE DIGNITY OF PROCREATION REPLIES TO CERTAIN QUESTIONS OF THE DAY.” The Holy See. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_19870222_respect-for-human-life_en.html. ↵

- Macklin R. In Seminars in reproductive medicine. New York, Beijing: © Thieme Medical Publishers; 2010. The ethics of sex selection and family balancing. ↵

- Macklin R. In Seminars in reproductive medicine. New York, Beijing: © Thieme Medical Publishers; 2010. The ethics of sex selection and family balancing. ↵

- “Controversies in Gender Selection.” International Congress Series 1271 (September 1, 2004): 345–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ics.2004.05.126. ↵

- Parents. “Gender Selection and IVF: What You Need to Know.” Accessed September 12, 2023. https://www.parents.com/getting-pregnant/gender/selection/ivf-and-gender-selection-what-you-need-to-know/. ↵

- “Elective Gender Selection of Human Embryos during IVF: Ethical and Public Policy Considerations.” In Human Embryos and Preimplantation Genetic Technologies, 29–34. Academic Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816468-6.00004-7. ↵

- Goedeke, S., Daniels, K., Thorpe, M., & du Preez, E. (2017). The Fate of Unused Embryos: Discourses, Action Possibilities, and Subject Positions. Qualitative health research, 27(10), 1529–1540. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316686759 ↵

- Macklin R. In Seminars in reproductive medicine. New York, Beijing: © Thieme Medical Publishers; 2010. The ethics of sex selection and family balancing. ↵

- Macklin R. In Seminars in reproductive medicine. New York, Beijing: © Thieme Medical Publishers; 2010. The ethics of sex selection and family balancing. ↵

- Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. “Gender Ratio.” Our World in Data, June 13, 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/gender-ratio. ↵

- Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. “Gender Ratio.” Our World in Data, June 13, 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/gender-ratio. ↵

- Goedeke, S., Daniels, K., Thorpe, M., & du Preez, E. (2017). The Fate of Unused Embryos: Discourses, Action Possibilities, and Subject Positions. Qualitative health research, 27(10), 1529–1540. ↵

- Goedeke, S., Daniels, K., Thorpe, M., & du Preez, E. (2017). The Fate of Unused Embryos: Discourses, Action Possibilities, and Subject Positions. Qualitative health research, 27(10), 1529–1540. ↵

- Simopoulou, M., K. Sfakianoudis, P. Giannelou, A. Rapani, E. Maziotis, P. Tsioulou, S. Grigoriadis, et al. “Discarding IVF Embryos: Reporting on Global Practices.” Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 36, no. 12 (December 2019): 2447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-019-01592-w. ↵

- Macklin R. In Seminars in reproductive medicine. New York, Beijing: © Thieme Medical Publishers; 2010. The ethics of sex selection and family balancing. ↵

- Alexander, Vinita M., Joan K. Riley, and Emily S. Jungheim. “Recent Trends in Embryo Disposition Choices Made by Patients Following in Vitro Fertilization.” Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 37, no. 11 (November 2020): 2797–2804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-020-01927-y. ↵

1 comment

Mariana Chamorro

Lia, your article is clear and informative. I like how you’ve explained each step of the process in easy-to-understand language. Your discussion of the ethical issues surrounding gender selection raises important questions about the impact of these practices on society. I enjoyed reading it!