Two and a half months before her execution, at two in the morning, the Queen along with her daughter and sister-in-law were suddenly awakened and informed that the Queen was to be transported to the prison of Conciergerie. Without protest, Marie Antoinette got dressed and bid farewell to her family members. Then, without looking back, she left the temple. Fifteen minutes later, the Queen arrived in front of the grim towers of the Conciergerie, where she was registered under the name of “The Widow Capet” and became its 280th prisoner.5 She was led by the jailers to her new quarters. It was a dungeon of fifteen square meters with walls covered with an old cloth stained by humidity. It also had a narrow window at ground level that let in a pale light. Her only furniture consisted of a camp bed, two straw seat chairs, a convenience chair, and a bidet. Only a screen shielded her from the gaze of her guards and gave her no privacy at all. An assigned maid did everything she could to improve the Queen’s conditions during captivity.6

Alexander de Rougeville was loyal to the Republic at the beginning of the revolution; however, after he witnessed the Queen’s misfortune, he decided to help her to freedom. He had formerly been part of the Comte de Provence’s military establishment and was one of the officers who had protected her on June 20, 1792. That day, angry mobs broke into the Tuileries and forced the King to acknowledge the Republic. In addition, Marie Antoinette was insulted and called a traitor of France. In early September, he accompanied the royal family’s jail administrator Jean-Baptiste Michonis to the Conciergerie with two carnations pinned to his lapel. A plan called the Carnation Plot was attempted to aid the Queen to flee the country. Marie Antoinette picked up the flower and inside, the petal concealed a tiny note, which the Queen attempted to answer by pricking out a message with a pin. However, the gendarme on duty noticed her actions, took the incriminating evidence, and gave it to his immediate superiors. The name of the plot was taken from a flower that a certain Rougeville dropped at the Queen’s feet in her cell. The idea was for Marie Antoinette to escape to the château of Madame de Jarjayes. She was the Queen’s lady in waiting and her husband was General de Jarjayes, a loyal follower of the royal family. The Queen would then be transported to Germany, which was under the rule of Austria, Marie Antoinette’s homeland. The plot failed, but before the Republic could send the guards to capture him, Rougeville managed to escape.7

In the former Grand Hambre of the Palais de Justice, the Queen of France appeared before the Revolutionary Tribunal dressed in black and wore a widow’s bonnet in white lawn and trimmed with black mourning crepe. The Republic gave her lawyers less than a day to prepare a defense. One of the accusations against her was that she had been one of the instigators of the Champ-de-Mars massacre of July 1791, and that she had sent money out of the country to her brother, the Holy Roman Emperor. In addition, she was accused of scandalous conduct with her son, and that she had instigated most of the crimes that Louis XVI had committed. Marie Antoinette refused to respond to any charges. However, Marie Antoinette believed that she was innocent of these crimes and did everything within her power to save the monarchy as she conceived it. The entire trial started from October 15, 1793 at eight in the morning and ended on October 16 at four-thirty in the morning.8

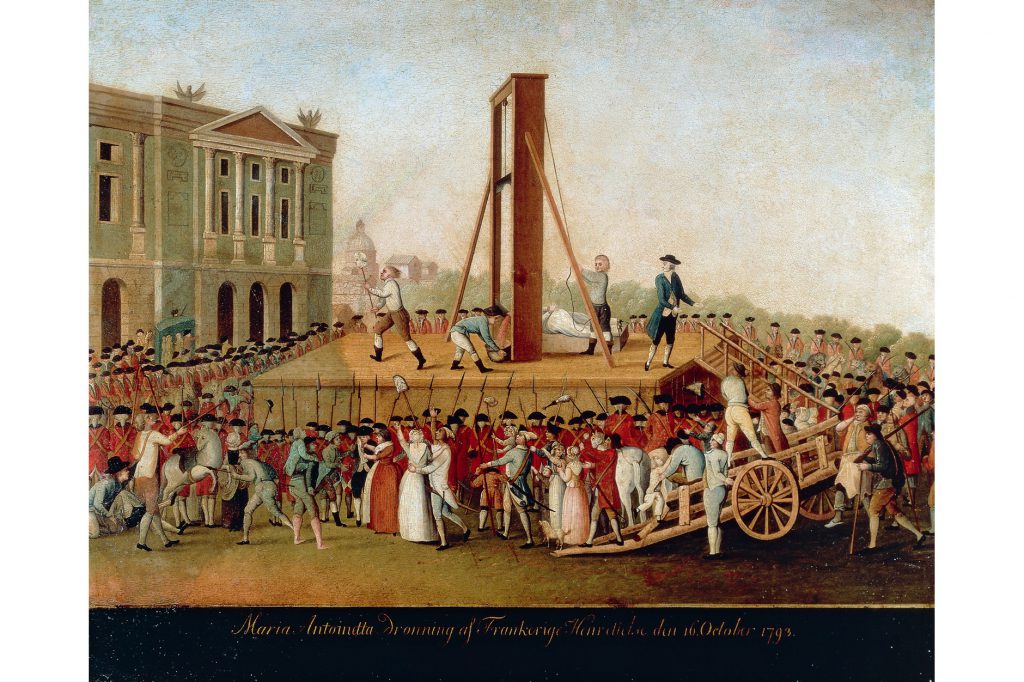

On October 16, 1793, at four-thirty in the morning, Marie Antoinette was declared guilty of the three main charges of having secret agreements with foreign powers, of shipping money aboard to Austria, and of conspiring with these powers against the security of French. After ten weeks in the Conciergerie, the Queen’s incarceration came to an end. She was sentenced to death by guillotine and yet she remained impassive and simply shook her head at the verdict. As stated by Chauveau-Lagarde, Marie Antoinette showed true courage and was void of any negative emotion.9 Once returned to her cell, the Queen wrote a farewell letter to Madame Elisabeth, her sister-in-law. During the preparation for her execution, Rosalie witnessed the planned humiliation carried out on Marie Antoinette. First, she was obliged to prepare herself under the gendarmes’ watchful eyes. When she attempted to undress in a little niche between the wall and the bed, she signed to Rosalie to shield her. However, one of the men came around and stared at her. The humiliation continued when Charles Henri Sanson came and hacked off her thin white hair with enormous scissors. Marie Antoinette was also told her hands must be bound, even though the late Louis XVI hadn’t had his hands bounded. The next humiliation occurred when she was overcome with weakness and asked to have her hands unbound and squatted in the corner. Having relieved herself, she meekly held out her hands to have them bound again.10

The day was fine and slightly misty, as huge crowds lined the route to the Place du Carrousel’s guillotine and listened to the cries of the escort: “Make way for the Austrian woman!” and “Long live the Republic!”11 Mainly the crowd heard these cries with satisfaction. By the time the cart reached the Place du Carrousel, she was sufficiently in command of herself to step down easily. Stepping lightly “with bravado,” she sprung up the scaffold steps despite her bound hands, and paused only to apologize to her executioner for stepping on his foot.12 So she went willingly, even eagerly, to her death. The head of Marie Antoinette, desired by the leaders of the French Revolution, was cut off cleanly at 12:15 on Wednesday, October 16, 1793, and was exhibited to a joyous public.

On the very day of the execution, the Queen’s mutilated body was taken to the small cemetery of the Madeleine, where the King’s body had been left nine months earlier. On November 1, a gravedigger buried the Queen’s remains and sent the following note to the multiple authorities. “The widow Capet. 6 livres for the coffin. 15 livres, 35 sols for the grave and the gravedigger.” These words described the funeral of the last Queen of France.13 With the restoration of the monarchy, on January 18, 1815, the remains of the royal bodies were exhumed with the help of Pierre Louis Desclozeaux, an old lawyer who lived at 48 rue d’Anjou. He remembered the two interments and had subsequently tended the sites. He created a garden out of the area and planted two weeping willows as a commemoration. The bodies were then briefly held at the house in the rue d’Anjou. Prayers were said before they were sealed in new coffins with appropriate inscriptions of the majesty and titles of the occupants. On January 21, 1815, a formal procession led the coffins to the Saint Denis cathedral.14 Commemorative statues of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were built in the cathedral and their remains were reburied in the Bourbon vault.15

No longer considered one of history’s greatest criminals, the last Queen of France today arouses interest and compassion. After her death on the scaffold, Marie Antoinette entered the world of legend and became a mythical figure.16 Being a scapegoat for the revolution, the Republic’s political decision for her execution united France. Despite being a sacrifice for the French, she never lost her composure and retained her image as a dignified Queen until the last moment of her life.17

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 304-305. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 213. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 250-259. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 287-290. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 291-292. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 292. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 293-294. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 299-304. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 435-438. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 438-440. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 439. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 440. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 305. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 447. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 457. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 308-309. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 453. ↵

80 comments

Carlos Serna

I always remember Marie Antoinette as the woman who wanted cake. I did not even know that she was the Queen of France and neither I thought that she was executed after the French Revolution. Thanks to this article, I could imagine all the pain she went through in her life, and it is difficult to think that she was executed for crimes that she did not even do. Now, I can think of Queen Marie Antoinette as a more historical figure and not just as woman that loved cake.

Keily Hart

This is such an interesting and well written article! I did not know much about Marie Antoinette, but to hear about how cruel the revolutionary’s were to her is awful. Her trial and execution were so rushed and cruel. While it makes sense that the people of France would be angry at the royal family, it’s hard to believe that people could do such cruel and evil things.

Sophia Rodriguez

It is crazy to hear this woman go through so much pain, loss, and humiliation just to be accused of things she never did. Marie Antoinette seemed so calm and she never wanted to fight back. She just let these things happen to her. The humiliation of what the guards did to her and how she put her hands together to be bound again proves how strong she was.

Abilene Solano

Honestly, I don’t know how Marie Antoinette was able to maintain dignified and never losing her composure when her impending doom was coming. Even when the French people were humiliating her and accusing her of things that weren’t completely true, she still remained impassive about everything that was going on. Another thing I noticed while reading this article is that I didn’t know that after her death, she was actually found innocent and was no longer “considered one of history’s greatest criminals,” since in most history lessons involving the French Revolution just briefly mentions her execution and continue with the lesson so I like that the author mentioned that part in her article. Overall, it was an interesting article to read and the author did a good job detailing the events that were occurring (including what happened after her death).

Alexandria Wicker

This was a very informative and interesting article. I have only every know Marie Antoinette as the “let them eat cake” woman and never knew anything about her past. I find it crazy that in the past, this is how they dealt with the lives of people. One thing that kept me extremely interested throughout the whole article is that she never lost her poise. Through everything she went through, she kept her cool and took everything that she was getting with a sense of grace and poise.

Jourdan Carrera

This article gives an excellent insight into what happened while the royal family was in prison. Something that is normally just brushed aside as a side note before their execution. It really goes to show just how impactful the entire revolution was on not only the French people but also on the subsequent history of France as a whole. After this time France would constantly flip from a monarchy to a republic and life for many of the people of France, especially the nobility, would never be the same again.

Reagan Clark

I love how this article goes into the background and history of Marie Antoinette. This shows a side of her that I have not heard much about when learning about the history of France. Every time Marie Antoinette comes up in a conversation, she is only remembered as the person who said, “let them eat cake.” I know remember studying that her husband was not a very good person or king. This makes e feel pity for her. This article shows the struggles she went through and the horrors she faced once she was imprisoned.

Ana Cravioto Herrero

This was a very informative article! I had always heard the name of Marie Antoinette but I never knew that she was executed. It seems like the events could have ended differently if they were dealt with in a different way and with a different perspective, but it is interesting to see how problems were handled in the past. In addition, I think that it was such a bold statement of how she decided to remain poise and keep her image during it all.

Andres Ruiz

The execution of Marie Antoinette was a strange case of bad situations snowballing on top of itself. On the one hand, the nobility of France continually dismissed the grievances of the poor, and on the other hand, the angry mobs of French commoners, as well as the Foreign pressure, made the French revolutionaries believe that execution of the nobility was the only possible way to solve their grievances. This conflict’s death toll created a true tragedy in the history of France, however, one that created the Marianist Order, and allowed Napoleon, who is often cited as the source of many liberal reforms throughout Europe, to come to power and change France. One wonders if all this was necessary, and if the tragedy was unavoidable. Such conjectures, sadly, only exist in the hypothetical, and we are left to wonder at the bloody possibilities.

Andres Ruiz

The execution of Marie Antoinette was a strange case of bad situations snowballing on top of itself. On the one hand, the nobility of France continually dismissed the grievances of the poor, and on the other hand, the angry mobs of French commoners, as well as the Foreign pressure, made the French revolutionaries believe that execution of the nobility was the only possible way to solve their grievances. On one hand, many people died in the Reign of Terror. On the other hand, this would greatly decrease the influence of Monarchy and represent a shift in the way government and the state was run.