Two and a half months before her execution, at two in the morning, the Queen along with her daughter and sister-in-law were suddenly awakened and informed that the Queen was to be transported to the prison of Conciergerie. Without protest, Marie Antoinette got dressed and bid farewell to her family members. Then, without looking back, she left the temple. Fifteen minutes later, the Queen arrived in front of the grim towers of the Conciergerie, where she was registered under the name of “The Widow Capet” and became its 280th prisoner.5 She was led by the jailers to her new quarters. It was a dungeon of fifteen square meters with walls covered with an old cloth stained by humidity. It also had a narrow window at ground level that let in a pale light. Her only furniture consisted of a camp bed, two straw seat chairs, a convenience chair, and a bidet. Only a screen shielded her from the gaze of her guards and gave her no privacy at all. An assigned maid did everything she could to improve the Queen’s conditions during captivity.6

Alexander de Rougeville was loyal to the Republic at the beginning of the revolution; however, after he witnessed the Queen’s misfortune, he decided to help her to freedom. He had formerly been part of the Comte de Provence’s military establishment and was one of the officers who had protected her on June 20, 1792. That day, angry mobs broke into the Tuileries and forced the King to acknowledge the Republic. In addition, Marie Antoinette was insulted and called a traitor of France. In early September, he accompanied the royal family’s jail administrator Jean-Baptiste Michonis to the Conciergerie with two carnations pinned to his lapel. A plan called the Carnation Plot was attempted to aid the Queen to flee the country. Marie Antoinette picked up the flower and inside, the petal concealed a tiny note, which the Queen attempted to answer by pricking out a message with a pin. However, the gendarme on duty noticed her actions, took the incriminating evidence, and gave it to his immediate superiors. The name of the plot was taken from a flower that a certain Rougeville dropped at the Queen’s feet in her cell. The idea was for Marie Antoinette to escape to the château of Madame de Jarjayes. She was the Queen’s lady in waiting and her husband was General de Jarjayes, a loyal follower of the royal family. The Queen would then be transported to Germany, which was under the rule of Austria, Marie Antoinette’s homeland. The plot failed, but before the Republic could send the guards to capture him, Rougeville managed to escape.7

In the former Grand Hambre of the Palais de Justice, the Queen of France appeared before the Revolutionary Tribunal dressed in black and wore a widow’s bonnet in white lawn and trimmed with black mourning crepe. The Republic gave her lawyers less than a day to prepare a defense. One of the accusations against her was that she had been one of the instigators of the Champ-de-Mars massacre of July 1791, and that she had sent money out of the country to her brother, the Holy Roman Emperor. In addition, she was accused of scandalous conduct with her son, and that she had instigated most of the crimes that Louis XVI had committed. Marie Antoinette refused to respond to any charges. However, Marie Antoinette believed that she was innocent of these crimes and did everything within her power to save the monarchy as she conceived it. The entire trial started from October 15, 1793 at eight in the morning and ended on October 16 at four-thirty in the morning.8

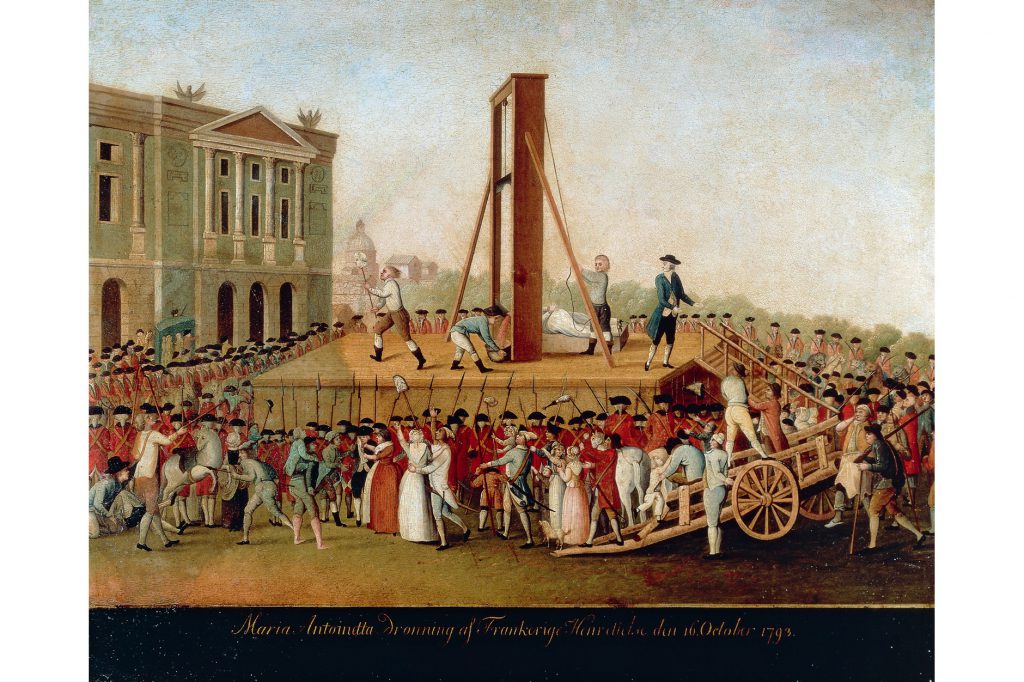

On October 16, 1793, at four-thirty in the morning, Marie Antoinette was declared guilty of the three main charges of having secret agreements with foreign powers, of shipping money aboard to Austria, and of conspiring with these powers against the security of French. After ten weeks in the Conciergerie, the Queen’s incarceration came to an end. She was sentenced to death by guillotine and yet she remained impassive and simply shook her head at the verdict. As stated by Chauveau-Lagarde, Marie Antoinette showed true courage and was void of any negative emotion.9 Once returned to her cell, the Queen wrote a farewell letter to Madame Elisabeth, her sister-in-law. During the preparation for her execution, Rosalie witnessed the planned humiliation carried out on Marie Antoinette. First, she was obliged to prepare herself under the gendarmes’ watchful eyes. When she attempted to undress in a little niche between the wall and the bed, she signed to Rosalie to shield her. However, one of the men came around and stared at her. The humiliation continued when Charles Henri Sanson came and hacked off her thin white hair with enormous scissors. Marie Antoinette was also told her hands must be bound, even though the late Louis XVI hadn’t had his hands bounded. The next humiliation occurred when she was overcome with weakness and asked to have her hands unbound and squatted in the corner. Having relieved herself, she meekly held out her hands to have them bound again.10

The day was fine and slightly misty, as huge crowds lined the route to the Place du Carrousel’s guillotine and listened to the cries of the escort: “Make way for the Austrian woman!” and “Long live the Republic!”11 Mainly the crowd heard these cries with satisfaction. By the time the cart reached the Place du Carrousel, she was sufficiently in command of herself to step down easily. Stepping lightly “with bravado,” she sprung up the scaffold steps despite her bound hands, and paused only to apologize to her executioner for stepping on his foot.12 So she went willingly, even eagerly, to her death. The head of Marie Antoinette, desired by the leaders of the French Revolution, was cut off cleanly at 12:15 on Wednesday, October 16, 1793, and was exhibited to a joyous public.

On the very day of the execution, the Queen’s mutilated body was taken to the small cemetery of the Madeleine, where the King’s body had been left nine months earlier. On November 1, a gravedigger buried the Queen’s remains and sent the following note to the multiple authorities. “The widow Capet. 6 livres for the coffin. 15 livres, 35 sols for the grave and the gravedigger.” These words described the funeral of the last Queen of France.13 With the restoration of the monarchy, on January 18, 1815, the remains of the royal bodies were exhumed with the help of Pierre Louis Desclozeaux, an old lawyer who lived at 48 rue d’Anjou. He remembered the two interments and had subsequently tended the sites. He created a garden out of the area and planted two weeping willows as a commemoration. The bodies were then briefly held at the house in the rue d’Anjou. Prayers were said before they were sealed in new coffins with appropriate inscriptions of the majesty and titles of the occupants. On January 21, 1815, a formal procession led the coffins to the Saint Denis cathedral.14 Commemorative statues of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were built in the cathedral and their remains were reburied in the Bourbon vault.15

No longer considered one of history’s greatest criminals, the last Queen of France today arouses interest and compassion. After her death on the scaffold, Marie Antoinette entered the world of legend and became a mythical figure.16 Being a scapegoat for the revolution, the Republic’s political decision for her execution united France. Despite being a sacrifice for the French, she never lost her composure and retained her image as a dignified Queen until the last moment of her life.17

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 304-305. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 213. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 250-259. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 287-290. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 291-292. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 292. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 293-294. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 299-304. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 435-438. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 438-440. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 439. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 440. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 305. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 447. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 457. ↵

- Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 308-309. ↵

- Antonia Frazer, Marie Antoinette: The Journey (NY: Doubleday, 2001), 453. ↵

80 comments

Antonio Holverstott

The punishment and execution of Marie Antoinette were flawed for a numerous amount of reasons. One reason was the application of ex post facto laws for things not inherently wrong under natural law done under the guise of another jurisdiction. She was accused of sending money to people in other countries, an action that was not illegal under the laws of imperial France since she was sending money to aid enemies to overthrow the country. In fact, her marriage with Louis was orchestrated as an act of diplomacy between Austria and France when she was a teenager. Another reason was wrongfully accusing her of committing a human rights violation by initiating a massacre in 1791. Marie Antoinette held no political power under the laws of France and was accused of not even focusing on the politics of nation because of her selfish focus on pleasure. In addition, the process of justice was based not on fact-finding but on personal revenge.

Hali Garcia

This is a very informative article. I learned about Marie Antoinette when I was in junior high and I learned a lot more after reading this article. What struck me was how she remained so strong and composed when she was sentenced. I feel sorry for her when she was humiliated because it was so completely different from what her husband faced. I would have thought that he would have been humiliated since he was the king, but I guess not.

Samuel Vega

This article gives us insight to Marie Antoinette or the Widow Capet. The Queen and her husband, King Louis XVI, were causalities of the French Revolution. They were blamed for the scarcity of food and the increased taxation that the French people revolted against. The King and Queen were captured during the revolt and sent to prison. It is interesting that Marie Antoinette kept her regal appearance as she was led to her execution. Once a queen, always a queen – even in death.

Sara Guerrero

The three charges put on Marie Antoinette and the verdict of the jury was extreme back in the day and it shows that someone could get executed for common crimes. I guess that I see it more as the people waiting to get rid of their reign, and maybe payback for their crimes. I felt bad for her when she was given no privacy at all in prison and the image of the guards watching her, like no woman should have to feel humiliated like that. She did stay strong and it’s like she knew what was going to happen to her in the end, but she never lost her composure.

Francisco Cruzado

The history of late-XVIII and early-XIX century France, is, for me, a tale of fighting against inequality. For example, for 1780, the 0.1% of the richest noble families in France had around 50% of the total “successions”; all for dropping to a 30% three decades later (1810), and then just growing again with Napoleon’s arrival. Additionally, the richest top-1% of France held 50% of all private property by 1780, while the lowest 50% did not even held a 5%. I personally found exciting reading this article, because it shows the humanity of an almost mythical figure as Marie Antoinette, and it certainly describes a French populace at the brink of madness (which may have been true, but not in its entireness, I think). I liked the details told in here: they engaged immensely the reader. I just wanted to point at data which is important to remember: despite the Queen being another human being, she was also for years, a monarch at the top of a society in which rural people were despised and mistreated.

Addie Piatz

I really did not know much about the French Revolution before reading this but it was really interesting to read about it from someone who was living in this time period’s perspective. My friend has tired to tell me about Marie Antoinette but it was much more intriguing reading it from their point of view. Great article, I really enjoyed it.

Malleigh Ebel

I did not realize that there were months between the king and queen’s executions. I thought they were executed together, and found it unfair how much more humiliating Marie Antoinette’s incarceration and execution was compared to her husbands. I never thought about Marie Antoinette’s side of the story when thinking of the French Revolution.This article was very eye-opening and showed even though she was faced with awful circumstances, she kept her composer.

Sydney Hardeman

This was a very well written article and it was very interesting to read. I did not know about the story of Queen Marie Antoinette, but her story shows that even royalty is not above the law, most of the time. It is interesting how her execution united France in a way in which she was a scapegoat for the French Revolution to take place.

Sebastian Azcui

The French Revolution was very harsh and many things happened. Many deaths, many wars, and lot of events that will stay forever in history. Marie Antoinette was a queen and she was charged for crime. She was found guilty of her crimes so she went to the famous French guillotine. She died being a queen, and thought that for being a queen she would be treated well in prison, and maybe she will not be charged of these crimes. But, she received the same treatment as everyone and ended dead.

Samantha Bonillas

I remember learning about the French Revolution in my history class and about Marie Antoinette. Reading this article in the point of view of someone who was alive during the revolution gave me insight and a whole new perspective. How Antoinette was viewed during the revolution gave her a bad reputation; however, reading about her now in this article, she was a different person than what she was given credit for. Great read.