On the day of March 5, 1770, roughly around 9:00 p.m. in Boston, Massachusetts, the tension between the Boston colonists and the British soldiers had reached its breaking point. Soldiers at this time were stationed in the colonies to protect and support the colony’s officials implementing the unpopular taxes on the colonists. Eight soldiers and one officer of the Twenty-ninth Regiment had been guarding the Custom-House on King Street when a mob of angry colonists, who were upset about the unfair taxes imposed on them by King George III, began to rally around them. The altercation had begun with the colonists verbally threatening the soldiers, but little by little things became worse. The colonist began to throw rocks and snowballs, and were even taking swings at the soldiers with clubs. Without being given the order to fire upon the colonists, the soldiers began to fire their muskets into the crowd of colonists, instantly killing three people in the mob and wounding eight others, two of whom were later pronounced dead. The five “victims transformed into the first martyrs of American independence,” wrote Hiller B. Zobel. The shooting became known as the Boston Massacre to all people in the colonies and as The Incident on King Street to the people of Great Britain.1

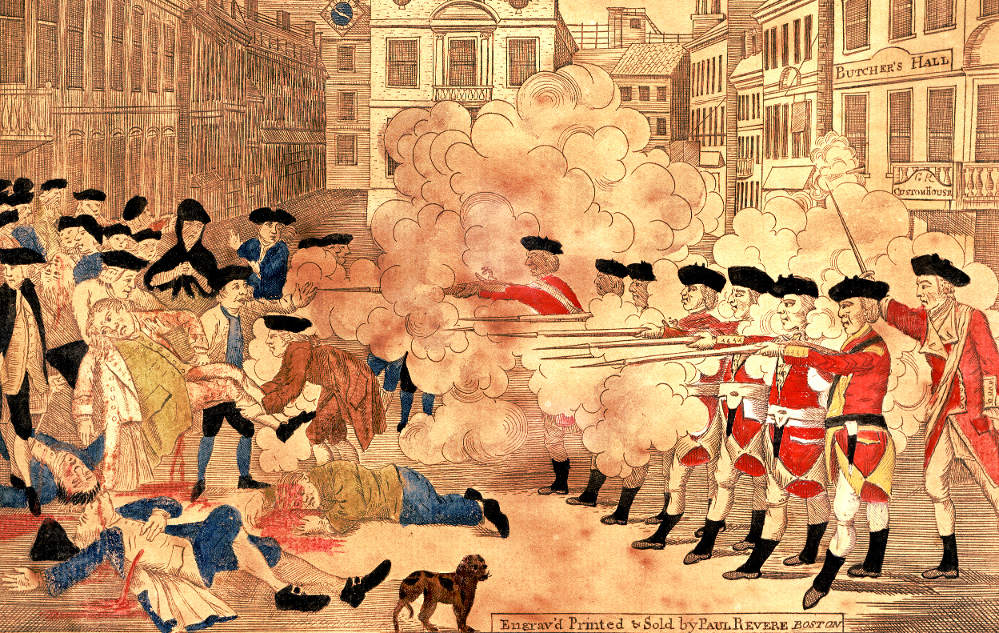

Patriots in Boston, such as Samuel Adams and Paul Revere (who painted the famous depiction of the soldiers firing on the crowd), were quick to have their local papers write about the shooting, labeling it a senseless act of violence on innocent by-standers. They believed this would help them get other Bostonians to hate the British soldiers occupying Boston. Shortly after the incident, by-standers were questioned on what had happened just moments ago, some of whom said they not only saw the soldiers on the streets firing on the people, but that they also saw fire coming from the second story of the Custom-House. The rumor was tested by a ballistics expert named Benjamin Andrews. He was able to track a bullet hole on a window from a business right across the street from the Custom-House, and he determined that the bullet came from “just under the stool of the westernmost lower chamber window of the Custom-House.”2 Local government noticed how much this incident riled up the people of Boston, and were committed to giving the soldiers and instigators a fair trial in court in order to prevent the British government as well as the Patriots from retaliating.

The soldiers had a hard time finding a lawyer to argue their case in court. Officer Preston, however, called for the future president and leading patriot John Adams to defend them. It was said that John Adams agreed to defend Officer Preston and the rest of the soldiers involved in the shooting in order to guarantee a fair trial for them. The town of Boston hired prosecutors Samuel Quincy and Robert Treat Paine to handle the cases of Officer Preston and the soldiers who were involved in the incident. Officer Preston and his soldiers were tried in separate trials.3

Seven months later, in October 1770, Officer Preston’s trial was held. After a lengthy trial, the jury in the case agreed that Officer Preston had not ordered his soldiers to open fire on the angry mob, and ultimately decided that he was not guilty of manslaughter, and he was acquitted from the crime. In the trial held for the soldiers, six of the eight were also found innocent and were acquitted; the two remaining soldiers were not so lucky. The last two soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter and were branded on the thumb as punishment, and then set free. Some people felt that the punishment did not fit the crime, but aside from the branding of the two soldiers, all soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre were withdrawn from the town and were “removed to the castle in the harbor” and were no longer there to enforce the unfair taxes on the people of Boston.4

- Hiller B. Zobel, “The Boston Massacre,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 4, (1970): 675. ↵

- O. M. Dickerson, “The Commissioners of Customs and the ‘Boston Massacre,'” The New England Quarterly Vol. 27, No. 3, (1945): 317. ↵

- Louise Phelps Kellogg, “The Paul Revere Print of the Boston Massacre, “The Wisconsin Historical Magazine of History, Vol. 1, No. 4, (1918): 377-387. ↵

- Louise Phelps Kellogg, “The Paul Revere Print of the Boston Massacre, “The Wisconsin Historical Magazine of History, Vol. 1, No. 4, (1918): 378. ↵

39 comments

Jourdan Carrera

This article examines the Boston massacre from an interesting angle. First it starts right where most Americans know the story, the British soldiers were guarding and then angry and upset colonists began to fight with them. The story we all know and love, however I very much enjoyed the background and after part of the topic, where the author examines the aftermath. Not the flashy aftermath that we all know as Americans, but the legal process and what actually happened to the individuals involved in the shooting. Both the commanding English officer and that British regulars who shot the musket balls which ignited a revolution.

Belene Cuellar

It’s interesting to see the many perspectives of this event and how it all played out in the end. I understand why the officers felt the need to protect themselves from the violent protest. Yes, I know it was wrong of them to kill those people, but they couldn’t just stand there and get beaten up by the protesters.

William Ward

It would seems in every textbook that the British soldiers massacred the citizens of Boston without reason, other than stopping a protest. Therefore, it is interesting to read about the different perspective especially that the Americans were apparently not protesting in a peaceful manner. Not pertaining to this article per say, but it is funny how the ability to distinguish the difference between good and bad people is blurred in history

Esperanza Rojas

It was surprising to read that Caesar was assassinated for not wanting to follow this “unwritten” constitution. I believed that Caesar was very unjust and unkind but it seems that he was the most fair ruler and the politicians didn’t like it, and it kind of seemed like the system used to be corrupt were the politicians were on top but with Caesar, the public came first.

Luke Lopez

This was a very informative article on the Boston Massacre. It is interesting that there are two conflicting stances on what actually happened during this incident. The soldiers claimed that the colonists threw rocks at them, and also hit them with clubs, which resulted in the soldiers firing on the colonists.The colonists claimed that the soldiers fired on them unwarrantedly.

Christopher Hohman

I liked this article. I like how you stated the two different names that are given to the event on either side of the Atlantic. It really shows that there are two sides to every story. Americans called it the Boston Massacre because they wanted to use it as propaganda, while the British referred to it as the incident on king street because they mostly saw it as a small incident, that would not effect the world the way it did. I am glad that most of the men were acquitted too. I do not think it was pre meditated, but rather that they got nervous and fired on the crowd because they were scared of being hurt.

Michael Thomas

I found this article interesting because of how it details the Boston Massacre. The colonists were beginning their revolt against the British. The British responded with violence, even though the protesters were unarmed. The British response to the protest led to more conflict with the colonist until the start of the Revolutionary War. Overall, the article was good and well written.

Samuel Stallcup

I remember learning about this in middle school, and being terrified about it. Mass killing in a public square? It’s terrifying to think about because of the tensions during this time period. Britain and the colonies were angry and upset with each other, and this massacre probably did not help anyone. I liked this article because it gave great details and allowed me to picture the horror.

Erik Shannon

This is a very interesting article. I did not have any previous knowledge on this topic before reading this article. I did not know a change in taxes can corrupt a civilization this easily. The British soldiers became hated by the colonists. The colonists threw what ever they had at the soldiers to show disgust and hatred. This was a very well written article.

Willyloman

Marissa Gonzales, the Tax issue was actually “No Taxation without Representation” (Meaning a King 3000 miles away cannot impose his will on the people without actual representation) and the Boston Massacre was supposed to happen. Those killed became Martyr’s of the revolution. The colonists needed a rallying point or flash point to start the revolution. This massacre was just one incident of many that took place in and around Boston Towne (Old English sp) that led up to Revolution. “No army shall Quarter themselves”, Printing Presses were destroyed by the British if the printers were printing articles that went against the King, or his army. High Taxes on exports/imports imposed by the King, Martial Law imposed on British Colonist’s..add all of this to High tensions and you have a Flash Point. I’m surprised that the writer of this article did not mention any of the surrounding agitations that led up to this Massacre.