Picture yourself in the eighteenth century. You are in the year 1765, and your business is going downhill due to the current recession in the British empire. Well, that was the reality facing Paul Revere and many other Boston business owners at the time. This recession was a consequence of the Seven Years’ War that the British fought on the European and North American fronts. The situation continued to worsen when the British Parliament, seeking to finance the empire in order to pay for the troops that were in the colonies after the Seven Years’ War, approved on March 22 of that year the Stamp Act. This act ruled that the colonists were going to pay a new tax, for no apparent reason, on various types of documents, papers, and cards, in the form of stamps attached to those documents. The precarious situation outlined above forced Revere to work as a dentist to earn a living. While this situation sounds like an unfortunate event for Revere, it would ultimately end up becoming a key moment for him, since one of his clients was Joseph Warren, a member of the “Sons of Liberty.” Paul would become close friends with Warren due to their similar political beliefs, and Warren would get Revere involved in the revolutionary movement.1

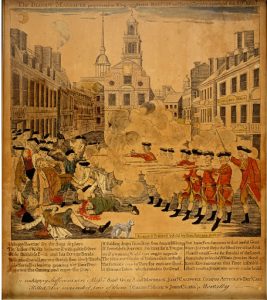

After the unpopular acts that the British Parliament passed in order to raise revenue through duties on lead, glass, paper, paint, and tea, tensions began to grow. The unrest of the colonists escalated until, on March 5, 1770, something happened: the Boston Massacre. What happened, basically, was that a crowd of colonists decided that facing off with eight armed British soldiers was a good idea. The Bostonians began to insult and threaten the soldiers, until the soldiers lost their patience and fired their muskets, killing five civilians. Following this tragic incident, the soldiers were brought to court. But to the chagrin of the Bostonians, none of the soldiers received a prison sentence. This case was highly publicized throughout the colonies, and the colonists felt nothing but anger and indignation over the verdicts, which contributed to increasing the unpopularity of the British regime among the inhabitants of the colonies. It was at this moment that Paul Revere began to earn a place in the history of the United States. Author Sean Lawler describes Revere’s moment this way:

“On March 5, 1771, only one year after the massacre, Paul Revere staged an elaborate public demonstration from his home in the North End. From the windows of his home, he displayed various scenes of the Boston Massacre. In one of his windows, he displayed the ghost of young Christopher Sneider along with the names of the five men that fell on King Street. A second window depicted the soldiers of the 29th regiment firing into the crowd, and the third window displayed lady liberty with one foot on the head of a British Grenadier, and her finger pointing toward the window displaying the massacre.”2

Revere’s window displays were very effective pieces of propaganda, since “The Bloody Massacre in King-Street” was a memorable image for many colonists. In a way, it helped unite them to see their cause as one for freedom and liberty. It is important to clarify that, maybe not very surprisingly, this performance was not an accurate depiction of the actual event. As with most pieces of propaganda, Revere used minor false elements and details in order to shape public opinion. First, Revere showed the soldiers lined up and an officer is giving the order to open fire. Second, the colonists are depicted as if they were reacting to an attack from the British soldiers, when in fact, the colonists were the agitators in this scenario. Finally, Revere completely erased an African American who was killed during the massacre.3

It is safe to say that Revere’s propaganda contributed to increasing the hostility of the colonists towards the British empire. In part, that hostility led to one of the biggest acts of protest and vandalism performed by the colonies against the British: the Boston Tea Party. The Boston Tea Party was led by two of the Sons of Liberty, Paul Revere and Joseph Warren. On November 28 of 1773, the merchant ship Dartmouth arrived in Boston Harbor carrying the first shipment of tea to be sold under the new terms of the Tea Act. Of course, the Patriots were not going to sit idly by; after a town meeting, they decided that the tea could not be disembarked; on the contrary, they wanted to return the cargo and refused to pay any type of tax on it.4 To make sure that the tea stayed aboard, they decided to have the North End caucus establish a rotating guard of over a dozen men, one of whom included Paul Revere. This guard was in charge of preventing the tea from being unloaded. The shipowner refused to depart until the colonies paid the duties on the cargo as established by law, so he decided to wait with his cargo of tea for the twenty days required of him to collect those taxes. This meant that he would remain in Boston Harbor with the tea until December 16. The Dartmouth had been joined by the Eleanor and the Beaver, and they remained in Boston Harbor. The day arrived, and the tea was never discharged due to the guards of the colonists. Earlier during this day, a plan was developed. Hundreds of men, disguised as Indians, boarded the ships. Led by Paul Revere and Joseph Warren, they then dumped into the Boston Harbor over £90,000 of tea. Something curious about this event is that they did all of this without destroying the property, and they repaired anything that they damaged. As Joe Miller writes, “No doubt this owed to the careful orchestration and oversight of men like Adams and Warren, and the execution of a handful of lieutenants like Revere.”5

After the Tea Party, Boston created a network of committees and a congress. Here again, Paul Revere played a prominent role. On December 17, 1773, he made his first of many revolutionary rides. Boston’s town meeting issued a justification for the Tea Party. They decided to create a committee of citizen leaders in order to spread the message throughout New England and certainly Paul Revere was in it. Revere’s job was to carry that message to the New York and Philadelphia Whigs. However, this would not be his only ride to these cities, as Revere would make at least five more trips to these two cities between 1773 and 1775. Each ride was a journey, taking into account the state of the roads in the eighteenth century. On most occasions, Revere rode his gray horse; however, sometimes he opted to use a small carriage as a means of transportation.6

Unsurprisingly, the British Parliament was quick to respond to these acts of vandalism perpetrated by the colonists, so they immediately closed Boston Harbor, repealed the Massachusetts charter, cut off most of the town council meetings, created a new court in the colony, and authorized imperial officials to send Americans to Britain for trials.7 These acts were perceived as “intolerable” by the American colonists. Clearly, they were not going to let this happen, so Paul Revere made a ride to New York and Philadelphia to help encourage resistance. During the summer, representatives from Suffolk County reunited and agreed that this was unconstitutional, and they recommended sanctions against Britain. This was called the Suffolk Resolves and it was drafted by Warren. After the meeting was concluded, Paul Revere saddled his horse in order to take the Suffolk Resolves to Philadelphia. David Fischer describes what happened this way: “Revere left Boston on September 11, 1774, and reached Philadelphia on September 16, nearly 350 miles on rough and winding 18th-century roads in the unprecedented time of five days. The next day congress agreed to a ringing endorsement of the Suffolk resolves—a decisive step on the road to revolution.”8 After this ride, he went back to Boston with news that encouraged resistance in New England. After spending a couple of days with his new bride, he took off again on September 29. This time, he was sent to visit leaders from New York and Philadelphia. On this occasion, he traveled in a sulky, or a two wheeled vehicle pulled by a horse. There were other short trips that Revere conducted during 1774 and early 1775. For over two years, Paul Revere was a key player in the American revolutionary movement. He was often called a messenger or an express rider, which perfectly described his role. Actually, his role was greater than that of a messenger, due to his leadership and dedication to the cause.

On April 7 of 1775, the British army instigated a troop movement, so Warren did not hesitate to send Revere to Massachusetts to give them a warning. He successfully delivered the message, and the war supplies of the minutemen were held safely in Concord. This would turn out be an important move, since one week later, on April 14, General Gage of the British army was given the following instructions by the secretary of state William Legge: “March with utmost expedition and secrecy to Concord, where you will seize and destroy all the artillery, ammunition, provisions, tents, small arms, and all military stores whatever.”9 Knowing that the “regulars” (British troops) were approaching, Revere gave instructions to Robert Newman, the sexton of the North Church, to send a signal by lantern to alert the colonists in Charlestown about the movements of the troops when the information became known. This is a well-known event today, made famous by the poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow:

He [Paul Revere] said to his friend, “If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry-arch

Of the North-Church-tower, as a signal-light,—

One if by land, and two if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country-folk to be up and to arm”.10

The British would ultimately take the water route, and therefore two lanterns were placed in the steeple.

The equestrian statue of Paul Revere in North End, Boston Cyrus Dallin was unveiled on September 22, 1940.

On April 18, Joseph Warren became informed that the troops were about to embark on boats from Boston to get to Lexington. Even though the colonists were one step ahead of the British, and the supplies in Concord were well guarded, they still had a problem. The regulars would probably try to go to Lexington and capture the revolutionary leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who were completely unaware of the danger. With this in mind, Warren immediately decided to send Paul Revere and William Dawes to warn them and to alert all of the colonial militias in the nearby towns. Revere rode through what we call now Somerville, Medford, and Arlington. During the ride, he warned every patriot that he could find, which had an exponential effect. By the end of the night, it is said that there were over forty riders carrying the news regarding the movements of the British Army. It is important to mention that Revere never said “the British are coming,” as this famous line is frequently attributed to him. In fact, not a single of the riders referred to them as “British.” As Fischer evidenced in his book, many New England express riders that night, including Revere, would speak of “regulars, redcoats, the King’s men, and even the ministerial troops…but no messenger is known to have cried-the British are coming.”11

Clearly, Revere’s plan required prudence, and, even though this might sound strange to our ears today, most of the Boston colonists at the time still considered themselves British. After delivering the news to all he encountered on his ride, he finally made it to Lexington. He met with Adams and Hancock, who were spending the night at the Clarke House. Hancock let him in, and Revere delivered the news to the two men. Revere asked if Dawes, the other express rider, had arrived already, but they told him that he had not. Fortunately, he arrived just thirty minutes after him, and they proceeded to have a drink with Revere at the tavern of the house. The four men discussed the mission of the British troops and, after a while, they came to the realization that Warren was wrong. The main objective of the mission was not the capture of Adams and Hancock. In reality, the mission of the regulars was to seize and destroy all war munitions from the colonies and deposit them in Concord.12 So clearly, delivering this new message was another task well suited for Revere and Dawes to complete. They saddled their horses again and, saying farewell to Adams and Hancock, departed westward on the road to Concord. On their way, they saw Samuel Prescot, a doctor, and he joined Dawes on the ride.

Everything was going according to the plan for Revere, until he, Dawes, and Prescott were detained by a British army patrol in Lincoln on their way to Concord. From the three riders, Revere was the one with the worst luck. Dawes and Prescott were able to escape, and Prescott was the only one who was able to make it all the way to Concord and deliver the message. Revere, on the other hand, was detained and questioned at gunpoint. Far from being afraid or intimidated, Revere spoke with calm humor. This triggered one of the officials who threatened Revere with a gun pointed to his head, that if he did not tell the truth, he was going to blow out his brains. Revere told him, “I call myself a man of truth, and you have stopped me on the highway, and made me a prisoner I knew not by what right. I will tell the truth, for I am not afraid.”13 After this, Revere proceeded to take control of the interrogation and spoke with a calm demeanor. His sole purpose was to move those men away from Lexington, since he was worried that they could capture the Whig leaders Adams and Hancock. Revere told the British that if their plan was to keep approaching Lexington, then they would be in extreme danger, since there were hundreds of armed men waiting for them. The officers listened closely, and after discussing among themselves in an altered mood, they decided to ignore Revere’s warnings, take him as a prisoner, and continue their way to Lexington. “We are now going toward your friends and if you attempt to run or we are insulted, we will blow your brains out,” said an officer to Revere, who replied, “You may do as you please.”14 They were going toward Lexington until they heard a gunshot; the officer demanded an explanation and Revere told him that it was a signal to alarm the country. Nevertheless, they decided to ignore Revere’s warning again, and they continued on their way to Lexington. As they got even closer, they heard Lexington’s town bell clanging rapidly. After this, one of the prisoners decided to heed Revere’s warnings and he told the officers, “The bell’s a’ringing! The town is alarmed, and you’re dead men!”15 After this, the British officers gathered together and decided to abort their mission. Now they were no longer interested in going to Lexington. Instead, they decided to free the prisoners, confiscate Revere’s horse, Brown Beauty, and run in the opposite direction to alert the approaching army.

It was the morning of April 19th when the battle of Lexington began. This was the first battle of the American Revolution. This would lead the colonists to write their Declaration of Independence in July of 1776. It is reasonable to say that Revere, even playing a supporting role, was key to the colonists. From his first ride until his famous midnight ride, Revere always got the job done with excellence. On the other hand, the romantic idea that Revere was a lonely rider who, by himself, warned the whole country is false, since dozens of other riders spread Revere’s message. But, as Fischer mentioned, “their participation did not in any way diminish his role, but actually enlarged it. The more we learn about these messengers, the more interesting Paul Revere’s part becomes-not merely as a solitary courier, but as an organizer and promoter of a common effort in the cause of freedom.”16

- Joel Miller, The Revolutionary Paul Revere (Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson, 2010), 102-104. ↵

- Sean Lawler, “Paul Revere,” Boston Tea Party, ships & museum, November 9, 2021, https://www.bostonteapartyship.com/paul-revere. ↵

- David Fisher, Paul Revere’s Ride (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1995), 21-22. ↵

- Joel Miller, The Revolutionary Paul Revere (Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson, 2010), 167. ↵

- Joel Miller, The Revolutionary Paul Revere (Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson, 2010), 163. ↵

- David Fisher, Paul Revere’s Ride (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1995), 26. ↵

- David Fisher, Paul Revere’s Ride (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1995), 26. ↵

- David Fisher, Paul Revere’s Ride (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1995), 27. ↵

- David Fisher, Paul Revere’s Ride (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1995), 85. ↵

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “Paul Revere’s ride,” Poets.org (website), 2021, https://poets.org/poem/paul-reveres-ride. Accessed 9 November 2021. ↵

- David Fisher, Paul Revere’s Ride (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1995), 110. ↵

- David Fisher, Paul Revere’s Ride (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1995), 111. ↵

- David Fisher, Paul Revere’s Ride (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1995), 134. ↵

- David Fisher, Paul Revere’s Ride (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1995), 135. ↵

- David Fisher, Paul Revere’s Ride (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1995), 136. ↵

- David Fisher, Paul Revere’s Ride (Norwalk, CT: Easton Press, 1995), 138. ↵

6 comments

Maria Jose Haile

I loved reading this article about Paul Revere- The first I learned about Paul Revere was way back in Elementary school when we had to do the infamous poem recitation about him which was as mention the one by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. I definitely could see that you did your research on this important topic. You made it very easy to read and understand, which I loved since I do love this topic.

Carlos Hinojosa

The first time I’ve ever heard of Paul Revere was all the way back in Middle School and he was just classified as the guy that said the British are coming. This article however showed me more of his past and why he was so important to the revolutionary cause. I’ve never heard of most of these stories, so this was a really good read and I hope to read more from you and the future. I could tell you researched very well.

Estefania Cala

I think it’s a very interesting article, very enjoyable and easy to read. It talks about a topic I didn’t knew about and would love to know more!

Hannah Young

I loved reading this article! It brought me back to my high school days when I actually knew this information but have now been refreshed with all this wonderful information over Paul Revere. I was shocked to find out some of the more personal details for his story but glad to know it was all backed up with tons of sites. Your amount of details in this small sized article is truly amazing!

Christian Hansen

Very well put together. Made the info very digestible and enjoyable to read.

Aidan Fitzgerald

Hi Santiago! I really enjoyed your article and story you presented us. I’ve always been fascinated in Paul Revere and his midnight ride but you certainly expanded my knowledge on the subject significantly. I thought you kept me interested throughout the entire article and used some intriguing language which told the story well. I think you picked a great topic, certainly an interesting one and gave the reader a much deeper insight than the general knowledge we learn in school.