Winner of the Spring 2017 StMU History Media Awards for

Best Article in the Category of “Gender History”

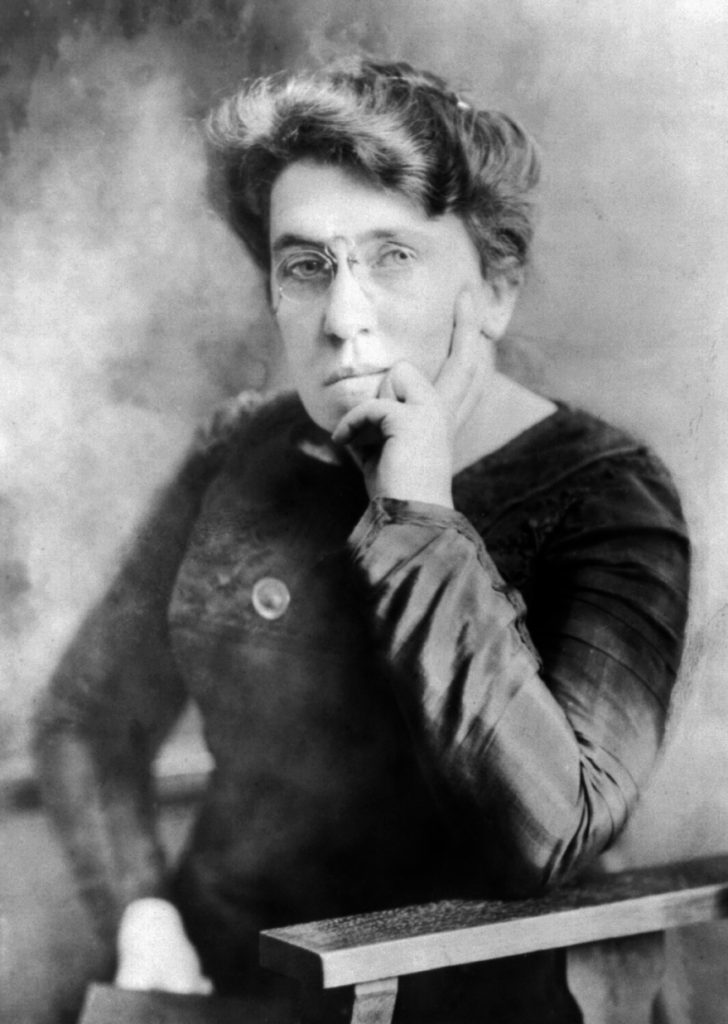

Emma Goldman, who would later in life be a known anarchist and women’s rights activist, had a very dismal beginning to life. Emma Goldman was born on June 27, 1869 in Kaunas, Lithuania, which was then known as Kovno, Lithuania. The dynamic of the family was unique as well, as Emma had two older sisters who were born from her mother, Taube Binowitz Zodikow, from her first marriage. Taube’s first husband and father to her two eldest daughters, Helena and Lena, passed away leaving Taube a widow. From this death, Taube entered into an arranged marriage with Abraham Goldman, resulting in the birth of Emma. During Emma’s childhood, she endured beatings from her father frequently, and her mother offered her no comfort. With this constant abuse and no support, Emma felt no sense of security in her household. This brought Emma into being raised with relatives in Königsberg, Germany. But in time Emma returned to the house of her parents Taube and Abraham, as being raised by the relatives in Germany was, if anything, worse by Emma’s standards, as she endured further neglect and abuse. But shortly after returning to her parents, they all moved to Königsberg, Germany, where Emma was luckily able to attend school. While she attended school in Germany, she became close friends with a teacher who gave her a first look into a new world she had never known of before. Music and literature came into Emma’s life and both proved to be lifelong loves of hers.1

Emma’s life took a drastic turn in 1881, when her family decided to move again, this time to St. Petersburg, Russia. In Russia, the Goldmans suffered financially and because of this drawback, Emma could no longer attend school. Money aside, her father did not support Emma’s schooling, as he believed there was no need for a woman to have any schooling. Emma’s love for learning and hope of becoming a doctor had been shattered right in front of her, yet she still remained on a path like no other. She became rebellious of her father’s ideals and his cultural traditions, including the Jewish faith. Emma Goldman had become introduced to the ideas of radicalism and she became further knowledgeable on a wider variety of subjects. A main source of inspiration for Emma was reading Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s novel What Is to Be Done? A character in the novel, Vera Pavlovna, gave inspiration and hope to Emma. Emma’s father had begun arranging for her to be married, but as Emma read of Vera’s idea that “rejected this practice as it is the auctioning of a sex object,” Emma, too, became a strong believer in rejecting arranged marriages.2

Emma was in despair at the life she had set out before her, so in 1885, she and her sister Helena moved to the United States. While Emma hoped for a new world to open up for her in Rochester, New York, her hopes were not met. Her parents had followed her and her sister to the United States, and more talk of an arranged marriage was still being discussed. Emma felt trapped. She was still subject to nearly the same low-paying factory work that she had wished to escape by coming to America.3

Then inspiration struck Emma Goldman once again. She had read about the four men who had been executed for the 1886 bombings that had killed several people in Haymarket Square in Chicago. Emma believed that these men had been executed because they were merely suspected of being anarchists, and that there was no proof that they had actually been the ones who had thrown the bombs. This enraged Emma, as she saw this as an injustice brought upon these men. Emma saw a clear parallel in the way the United States was behaving toward radicals and the way Russia also dealt with radicals. With this fuse lit, Emma became a companion to those who opposed capitalism and the state.4

Emma Goldman, now living in New York’s Lower East Side, became acquainted with two men: Johann Most, the editor of the anarchist newspaper Die Freiheit (Freedom), and Alexander Berkman, a known anarchist figure in the United States. Emma came to see the idea of Anarchism as a “promised society based on judgement and reason.”5

Emma Goldman opposed the idea that corporations and states should hold all of the power and control in society. Schooled on Johann Most’s teachings on anarchism, Emma took to public speaking. In 1890, Emma was elated to find how effective she was at inspiring others. Emma spoke in both Yiddish and German, and one of her driving purposes was to provoke change in workers’ working conditions. She spoke of how miserable life was for these workers, working for companies with managers that saw them as merely interchangeable parts in a big machine.6

In time Emma became a natural speaker, and she branched out into discussing even more topics. She began to speak out about women in a way that had rarely been vocalized in public. She became an advocate for sexual and reproductive freedom for women. By 1900, birth control was becoming more openly discussed in public, and this discussion of birth control drew criticism. Many viewed discussing birth control in public as being obscene and indecent, and some women were even punished for speaking about this “indecency.” Emma Goldman let her voice be heard in this area, and she began to address larger and larger crowds. The more concerns she brought to her listeners’ attention, the more ears she attracted. She was a woman, center stage, and this made her stand out even more, as men could not speak so personally and intimately on this issue as she could.7

One thing limiting Goldman’s audiences was her choice in addressing them in German and Yiddish. When she began addressing them in English, she attracted even more listeners, and from a wider variety of backgrounds as well. With this growth in popularity, her name also became known to the police. They attempted to silence Emma, and even sentenced her to a full year in prison in 1893 for doing nothing more than speaking at a rally for the unemployed. This arrest did not silence Goldman, as she exclaimed that these government authorities “can never stop a woman from talking.”8 This year of detainment put no damper on Goldman’s goals, as she swore her life to teaching the principles of anarchism, and foremost to encourage others to question authority. To make matters worse for Emma’s standing, the population at large believed that anarchists were simply provoking senseless violence, as seen in the assassination attempt on Henry Clay Frick in 1892 by Emma’s close friend, Alexander Berkman, and the actual assassination of President William McKinley in 1901, who was shot by anarchist Leon Czolgosz. Goldman did not want this image of anarchism to be the accepted image, and she continued to speak openly in defense of anarchism. To make matters even worse, Goldman, who had been acquainted with Czolgosz, was being held in police custody for her supposed involvement in the assassination of McKinley. She was detained for two weeks before her release, as no evidence was found linking her to the crime.9

She continued to lecture, but with each arrival she did not know whether an arrest was imminent, or if she would simply be locked out of the premises she was meant to speak in. As the United States entered World War I, Emma Goldman’s lectures were seen as a threat to national security. After spending eighteen months in prison, she faced immediate deportation to Russia. Back in Russia, Goldman found herself practically and completely miserable. Her anarchist ideas were not accepted in Leninist Russia, and she felt betrayed and rejected. And now Emma faced another hatred: antisemitism. Emma was now being viewed and looked at solely because of her Jewish background. With the rise of anti-semitism came another threat: totalitarianism. Goldman saw this threat and took action. She now began to lecture on totalitarianism, and how she identified it in the forms it had been taking in Italy and Germany.10

“The most violent element in society is ignorance.”

Emma Goldman could not escape the title people gave her as being just another “Jewish woman.” Criticism came to her because of this and she even stated, “life was linked with that of the race.”11 On the contrary, Emma Goldman kept her head up. Candace Falk says Emma envisioned herself as “a woman who could transcend the boundaries imposed by the stereotypical social constructions of religion.”12 Emma would express herself through written word as time progressed. Nearing the last few years of her life, in 1937, Emma showed her concern even more for the striking rise of Nazism. Emma took to writing about this now because of her shock in learning about Adolf Hitler and all that he proposed. She wanted to exclaim how she had fought so hard for the right of a good life for the Jewish community, and she wanted to emphasize how Jewish culture was not to be annihilated, but appreciated for its contributions. She dreaded the future that was to come, and she urged the need for countries to take in Jewish refugees. Only three years later, in 1940, Emma Goldman unfortunately died from a stroke in Toronto, Canada where she lived in hopes that she would be allowed to visit the United States.13

Emma Goldman stood up for many things throughout her life, and did not hide her voice from the crowd. She persevered, she never gave up on her ideas and beliefs. She stood up for those who needed to be heard and she did not apologize for it. She was feared, and she was adored. She, in herself, is a symbol of free expression and through this she wanted people to follow in her footsteps. She wished for a better world for those who were oppressed. She wanted a world where women were looked at as being more than their physical bodies. She fought for equality and she fought for fair treatment. Emma Goldman was a woman who was not afraid to speak when so many tried to silence her.

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2008, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Lloyd J. Graybar. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2008, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Lloyd J. Graybar. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2008, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Lloyd J. Graybar. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2008, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Lloyd J. Graybar. ↵

- Jewish Women’s Archive, March 2009, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Candace Falk. ↵

- Jewish Women’s Archive, March 2009, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Candace Falk. ↵

- Jewish Women’s Archive, March 2009, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Candace Falk. ↵

- Jewish Women’s Archive, March 2009, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Candace Falk. ↵

- Jewish Women’s Archive, March 2009, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Candace Falk. ↵

- Jewish Women’s Archive, March 2009, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Candace Falk. ↵

- Emma Goldman, Living My Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1931), 704. ↵

- Jewish Women’s Archive, March 2009, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Candace Falk. ↵

- Jewish Women’s Archive, March 2009, s.v. “Emma Goldman,” by Candace Falk. ↵

124 comments

Ana Cravioto Herrero

Great article! I am very surprised I had not heard of Emma Goldman until now, and I think we should be learning about woman like her in our history classes. She went through a lot of struggles, and despite it all, she never gave up. She is so admirable and it is woman like her that gave us woman our voices today.

Patricia Arechiga

I am pretty shocked that I have not heard of Emma Goldman before considering the fact that she was one of the most vocal individuals throughout her time period. She reminds me of MLK as both spoke out about social justice issues. I find it beyond motivational as to how Emma kept pushing towards change despite being arrested and voiced down by those who sustained authority. Despite her rough childhood, she used the injustices she went through as motivation for change.

Tala Owens

I’m glad to have heard about this woman after reading this article. She had a rough childhood that she did not deserve. I;m glad she knew that she didn’t deserve to be treated like she was less or like an object by her family and never gave up fighting for what she believed in, it’s very admirable, especially with the way women were treated in society at the time.

Fatima Navarro

I had never heard of her before. Sadly she was also Jews on top of being a woman, and that made it even harder for her. It is even sadder that she ended up dying of a stroke before returning to the United States while staying in Canada. I really enjoyed this article, it was also well-written. There is no surprise ti was given an award. I appreciate stories of woman who fought to be heard back in the days when, just as Emma’s dad implied, women studying was a waste of time.

Danielle Slaughter

This was a very well-written article on a controversial yet inspiring woman. While I do not agree with Ms. Goldman’s views on anarchism and capitalism, I am always in the corner of a woman who is not afraid to speak her mind whenever it is right to do so, or when she feels compelled to stand up for those who cannot stand themselves. All in all, a superb article definitely deserving of that award. Well done!

Victoria Rodriguez

I have never heard of Emma until now! Which is surprising seeing that she was so active with her voice and that she had quite a lot to say. I think that women like this are downplayed in history and that with this article her character and morals were honored. This was obviously a great article, but even more important it was a very meaningful one. Congratulations!

Luis Magana

When I read the title my first thought was of a dangerous women who committed some type of dangerous crime. Emma isn’t a criminal but a smart brave women who was beaten and put down. She did not let that stop her but kept fighting on and didn’t let anything put her down. Using words is an extremely powerful tool. Words hurt more than getting hit because words stay in your head a bruise can heal. I loved reading this article it was very interesting.

Engelbert Madrid

I like the fact that Emma Goldman didn’t give up, although majority of Americans did not want to hear her ideas and beliefs. She was definitely a strong, Jewish woman who used her voice for women and for workers that were not receiving enough financial and social support. Her quote that states, “The most violent element in society is ignorance,” is crucially significant in the times that she was living, because people just followed others and their ideologies without confronting them. Emma demonstrated that she could be a leader even if the majority rejected her ideas.

Raymond Munoz

It’s saddening to hear that in a country of freedom of speech Emma Goldman was kicked out of the country for speaking up. I have heard a defense that basically says, “Yes you have the right to speak your mind, but you also have to accept the consequences of speaking up whether it’s positive or negative.” I understand this defense and how in some cases people do get a little aggressive with their opinions and can’t be allowed to harm the community, but at the same time I don’t believe such strict measures of deporting someone is necessary. All in all, this was a very informative article with great sources.

Belene Cuellar

This is a truly inspiring article for everyone out there afraid to speak the truth and rise above those who are oppressing freedom. Back in the day it was improper for a woman to even speak out for herself and yet she still did it. She didn’t care about the consequences and so she spoke out for her beliefs and for everyone that felt discouraged.