Many important lasting security struggles around the world, and especially on the African continent, are repeatedly overshadowed by other singular or flaring crises or by extraordinary natural disasters. In the case of the indigenous peoples of the Western Sahara, the Sahrawis, their struggle to regain their territory lost during colonial times is an ongoing conflict hardly ever mentioned in International News. Ever since Spain withdrew from the region in 1976 with no clear plan for the transition of power, Western Sahara, located in the North-West region of the African continent, has been contested by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) led by the Polisario Front, a national liberation movement fighting for independence of Western Sahara, against Morocco for over 45 years.1 Morocco claims ownership over Western Sahara from before Spain colonized it in 1884, and the Polisario Front advocates for territorial sovereignty belonging to the region’s indigenous population, the Sahrawis.2 & 3 The ceasefire established in 1991 led to a stalemate between Morocco and the Polisario Front; however, after almost twenty years, the Polisario Front broke the ceasefire, calling for a complete withdrawal of Moroccan troops from the Western Sahara.4 The conflict over the Western Sahara territory “had disastrous human, economic, and political consequences across Northern Africa,” even before the most recent violations of the ceasefire.5 Thousands of Sahrawis are displaced from their homes, and the estimates reach upwards of 170,000 people who had to flee the violence.6

Displaced Sahrawis are living in refugee camps within the Tindouf Province of Algeria, and are facing harsh conditions of exile, isolation, and poverty.7 Under international law, the Sahrawis living under the control of the Polisario Front bear the burden and implications of statelessness, with thousands killed because of the lack of protection.8 & 9

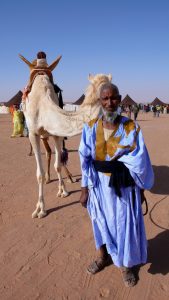

The Sahrawis have a rich and profound cultural and religious history, including a mix of various cultures and ethnicities. The Sahrawis are traditionally nomadic Berbers, yet distinct from Berber Tuareg nomads in the east, Arab, and black African descent.10 The period of Spanish colonization brought many Spanish traditions to the Sahrawis, even having Sahrawi youths above the age of 13 live and study with Spanish host families.11 Sahrawis, like Moroccans, practice Sunni Islam, practiced by 99.9% of the population. However, although most of the population of Western Sahara practices Sunni Islam, there are small minority Christian groups, such as Moroccan Christians and foreign Roman Catholics, as well as non-Muslim foreigners who work in the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara.12 The Polisario Front also claims to uphold a secular governance approach; however, “more recently there had been “rapprochement of some elements of the Polisario with Islamist terrorism.”13

The Green March was a mass mobilization into the Western Sahara of 350,000 Moroccans that lasted four days, including over 300,000 Moroccan citizens, over 40,000 government officials, and King Hassan II claimed everyone who participated volunteered.23 King Hassan II also deployed troops “along the northwest region of Western Sahara… to fend off any external interference from other African countries.”24 With the complete removal of Spain from the Western Sahara, Morocco and Mauritania joined forces against the Polisario Front, who were supported by Libya and Algeria, and the Western Sahara War commenced.25 The Western Sahara War carried on from 1975 to 1991, and in 1979, Mauritania withdrew from the conflict, signed a peace treaty with the Polisario Front, and recognized the SADR.26 Although Morocco and the Polisario Front established a ceasefire in 1991, and France recognized Morocco’s claim of sovereignty over Western Sahara in July 2024, tensions between Morocco, the Polisario Front, and the Sahrawis were still brewing, which led to the end of the ceasefire in 2020.27

Security challenges have persisted since the conflict over Western Sahara began. The presence of natural resources in the Western Sahara stood at the heart of the fierce altercations and motivated the Spanish colonization. The Western Sahara holds a considerable amount of phosphorus, so much so that in 2018 alone, Morocco shipped over 1.9 million tonnes of phosphate out of Western Sahara, estimated at over $160 million.28 Under Morocco’s state-owned company “OCP SA,” Morocco has held steady control over the Bou Craa mine, which holds most of Western Sahara’s phosphorus deposits.29 Morocco has controlled the Bou Craa mine for almost 50 years since Spain withdrew from the region in 1976.30 The Sahrawis have “consistently protested the trade, ” claiming the territory rightfully belongs to them.31

With the breakdown of the 1991 ceasefire agreement by the Polisario Front and the return of active violence, more security issues continue to arise. Although the Polisario Front has returned to its armed campaign, the Sahrawis have been broadly supporting the offensive measures because of the ineffective peace process led by the United Nations, and even pressuring the Polisario Front to use force to alter the status quo.32 With over 170,000 Sahrawis living in the refugee camps of Tindouf, Algeria, they are eager to see the Polisario Front resist against not only Morocco, but even “international calls to de-escalate the conflict and return to negotiations.”33 Furthermore, the Polisario Front’s leaders are now facing a generational transition, with many of the leaders well into their 60s and 70s, causing further challenges for the resistance group.34

The Sahrawis anchor their culture in traditions passed from generation to generation through oral storytelling. Yet, technology has inserted a new dimension into the conflict over the past decade in the area of cyber warfare. Today’s conflicts require not only a boots-on-the-ground approach, but also prioritizing one’s defenses for the digital space, a key target for many nations and most vulnerable to incursion by hacktivist groups. In terms of the Western Saharan conflict, pro-Algerian hacktivist groups took on the digital playing field and launched cyber attacks at Morocco.40 The cyber attacks include “(Distributed Denial of Service) (DDoS) attacks, data theft and leaks, and website defacement.”41 There have also been cyber attacks that have specifically targeted Moroccan and Western Saharan activists.42 A new mobile malware known as “Starry Addax,” which “pretends to be a variant of the Sahara Press Service app, run by a media agency associated with SADR,” has been uncovered by researchers of the “Cisco Talos and the Yahoo Advanced Cyber Threats Team.”43 & 44 The malware spreads through phishing attacks, steals sensitive information from victims’ devices, and tricks victims into downloading more malware, including ‘FlexStarling,’ “a versatile Android Trojan that… allows the attacker to control infected devices.”45 & 46 Drone strikes have also emerged due to the escalation of this digital fight.

The conflict has already taken lives on both sides. A Sahrawi military leader was killed in a drone strike in April 2021, several Sahrawi fighters and a Polisario Front commander were killed in October 2023, and the Polisario Front fired rockets into the Al-Mahbes, a UN-monitored buffer zone in Western Sahara, in October 2024.47 & 48 In the neighboring Sahel region, levels of terrorist attacks, recruitment of youth, and support for military coups have infected all bordering countries to the east and south. The Sahel region spans from North-East Africa, Eritrea, to North-West Africa, Senegal, and partially into Mauritania, which both border Western Sahara.49 The growing level of terrorism in this part of Africa, more particularly, the adjacent Western region, poses significant security challenges for Western Sahara and its regional instability. With Western Sahara currently amidst a major conflict between the Polisario Front and Morocco, and the region not recognized as an independent state, but instead “a Non-Self-Governing Territory lacking any administrative power,” it creates a security vacuum that terrorist groups within the Sahel region might want to exploit.50 & 51 Terrorist groups such as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and the Islamic State in the West African Province (ISWAP) could capitalize on the security vacuum in Western Sahara and form shifting alliances to gain control of it.52 This national and human security risk only exacerbates the safety and predicaments the Sahrawis currently face.

- Chograni, H. (2021, June 22). The Polisario Front, Morocco, and the Western Sahara Conflict. Arab Center Washington DC. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-polisario-front-morocco-and-the-western-sahara-conflict/. ↵

- BBC. (2018, May 14). Western Sahara profile. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-14115273. ↵

- Chograni, H. (2021, June 22). The Polisario Front, Morocco, and the Western Sahara Conflict. Arab Center Washington DC. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-polisario-front-morocco-and-the-western-sahara-conflict/. ↵

- Chograni, H. (2021, June 22). The Polisario Front, Morocco, and the Western Sahara Conflict. Arab Center Washington DC, retrieved 3/30/2025, https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-polisario-front- morocco-and-the-western-sahara-conflict/. ↵

- Boukhars, A. (2024). Western Sahara: Beyond Complacency. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2013/10/western-sahara-beyond-complacency?lang=en. ↵

- The end of the ceasefire in Western Sahara. (2021). IISS. https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/2021/the-end-of-the-ceasefire-in-western-sahara/. ↵

- Western Sahara: The Cost of the Conflict. (2007, June 11). Crisis Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/western-sahara/western-sahara-cost-conflict. ↵

- Marilyn, A. (2024). The right to nationality of the Saharawis and their legal identity documents. Citizenship Studies, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2024.2321722. ↵

- 36. Morocco/Western Sahara (1976-present). (n.d.). Uca.edu. https://uca.edu/politicalscience/home/research-projects/dadm-project/middle-eastnorth-africapersian-gulf-region/moroccopolisario-front-1976-present/. ↵

- Saharawis in Morocco. (n.d.). Minority Rights Group. https://minorityrights.org/communities/saharawis/. ↵

- Reis, R. (2024, November 18). Western Sahara’s Sahrawi Refugees Face an Uncertain Future after 50 Years of Exile. Migrationpolicy.org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/western-sahara-sahrawi-refugees. ↵

- Davis, B. (2020, January 27). Educator of the Faithful: The Power of Moroccan Islam | Hudson. Www.hudson.org. https://www.hudson.org/national-security-defense/educator-of-the-faithful-the-power-of-moroccan-islam. ↵

- Pham, J. P. (2010). Not Another Failed State: Toward a Realistic Solution in the Western Sahara. The Journal of the Middle East and Africa, 1(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520841003741463. ↵

- Morocco – Countries – Office of the Historian. (2020). State.gov. https://history.state.gov/countries/morocco. ↵

- Britannica. (2019). Western Sahara | Facts, History, & Map | Britannica. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Western-Sahara. ↵

- Britannica. (2019). Western Sahara | Facts, History, & Map | Britannica. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Western-Sahara. ↵

- Britannica. (2019). Western Sahara | Facts, History, & Map | Britannica. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Western-Sahara. ↵

- Giniger, H. (1975, November 15). Morocco and Mauritania In the Sahara Pact With Spain. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1975/11/15/archives/morocco-and-mauritania-in-sahara-pact-with-spain-madrid-agrees-to.html. ↵

- Parrilli, F. (2021). Sahrawi: An Endless Struggle for Independence and Freedom. Themigrationnews.com. https://www.themigrationnews.com/news/sahrawi-an-endless-struggle-for-independence-and-freedom/. ↵

- Parrilli, F. (2021). Sahrawi: An Endless Struggle for Independence and Freedom. Themigrationnews.com. https://www.themigrationnews.com/news/sahrawi-an-endless-struggle-for-independence-and-freedom/. ↵

- Corby, E. (2011, April 17). Moroccans march into Western Sahara in the Green March, 1975 | Global Nonviolent Action Database. Nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/moroccans-march-western-sahara-green-march-1975. ↵

- Corby, E. (2011, April 17). Moroccans march into Western Sahara in the Green March, 1975 | Global Nonviolent Action Database. Nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/moroccans-march-western-sahara-green-march-1975. ↵

- Corby, E. (2011, April 17). Moroccans march into Western Sahara in the Green March, 1975 | Global Nonviolent Action Database. Nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/moroccans-march-western-sahara-green-march-1975. ↵

- Corby, E. (2011, April 17). Moroccans march into Western Sahara in the Green March, 1975 | Global Nonviolent Action Database. Nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/moroccans-march-western-sahara-green-march-1975. ↵

- Zunes, S., & Mundy, J. (2010). Western Sahara: War, Nationalism, and Conflict Irresolution (p. 9). Syracuse University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1j2n9vz. ↵

- Chograni, H. (2021, June 22). The Polisario Front, Morocco, and the Western Sahara Conflict. Arab Center Washington DC. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-polisario-front-morocco-and-the-western-sahara-conflict/. ↵

- Chograni, H. (2021, June 22). The Polisario Front, Morocco, and the Western Sahara Conflict. Arab Center Washington DC. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-polisario-front-morocco-and-the-western-sahara-conflict/. ↵

- Western Sahara Resource Watch | New report on Western Sahara phosphate industry out now. (2019). Wsrw.org. https://wsrw.org/en/archive/4497. ↵

- Western Sahara Resource Watch | The conflict phosphates – four decades of plunder. (2023). Wsrw.org. https://wsrw.org/en/news/the-phosphate-exports. ↵

- Spain, Morocco, & Mauritania. Madrid Accords. (1975). ↵

- Western Sahara Resource Watch | The conflict phosphates – four decades of plunder. (2023). Wsrw.org. https://wsrw.org/en/news/the-phosphate-exports. ↵

- The end of the ceasefire in Western Sahara. (2021). IISS. https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/2021/the-end-of-the-ceasefire-in-western-sahara/. ↵

- The end of the ceasefire in Western Sahara. (2021). IISS. https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/2021/the-end-of-the-ceasefire-in-western-sahara/. ↵

- The end of the ceasefire in Western Sahara. (2021). IISS. https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/2021/the-end-of-the-ceasefire-in-western-sahara/. ↵

- Kushner, J., & Cheng, K.-C. (2024). Morocco’s War Against the Sahrawi. Pulitzer Center. https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/moroccos-war-against-sahrawi. ↵

- Kushner, J., & Cheng, K.-C. (2024). Morocco’s War Against the Sahrawi. Pulitzer Center. https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/moroccos-war-against-sahrawi. ↵

- Kushner, J., & Cheng, K.-C. (2024). Morocco’s War Against the Sahrawi. Pulitzer Center. https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/moroccos-war-against-sahrawi. ↵

- Fabiani, R. (2023, July 20). Paving the Way to Talks on Western Sahara. Www.crisisgroup.org. https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/western-sahara/paving-way-talks-western-sahara. ↵

- Reuters Staff. (2024, September 26). Algeria reimposes visa requirements on Moroccan nationals. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/algeria-reimposes-visa-requirements-moroccan-nationals-2024-09-26/. ↵

- Decoding Cyberattacks on Morocco – CYFIRMA. (2024). CYFIRMA. https://www.cyfirma.com/research/decoding-cyberattacks-on-morocco/. ↵

- Decoding Cyberattacks on Morocco – CYFIRMA. (2024). CYFIRMA. https://www.cyfirma.com/research/decoding-cyberattacks-on-morocco/. ↵

- Martin, A. (2020). Human rights activists in Western Sahara are being targeted by mobile malware. Therecord.media. https://therecord.media/android-mobile-spyware-western-sahara. ↵

- Martin, A. (2020). Human rights activists in Western Sahara are being targeted by mobile malware. Therecord.media. https://therecord.media/android-mobile-spyware-western-sahara. ↵

- Martin, A. (2020). Human rights activists in Western Sahara are being targeted by mobile malware. Therecord.media. https://therecord.media/android-mobile-spyware-western-sahara. ↵

- Decoding Cyberattacks on Morocco – CYFIRMA. (2024). CYFIRMA. https://www.cyfirma.com/research/decoding-cyberattacks-on-morocco/. ↵

- Decoding Cyberattacks on Morocco – CYFIRMA. (2024). CYFIRMA. https://www.cyfirma.com/research/decoding-cyberattacks-on-morocco/. ↵

- Presse, F. (2023, September). Polisario Commander, Western Sahara Fighters Killed By Drone. Barrons; Barrons. https://www.barrons.com/news/polisario-commander-western-sahara-fighters-killed-by-drone-c9d967fa. ↵

- Yabiladi.com. (2024, November 10). Polisario attacks civilians with projectiles in Al Mahbes. Yabiladi.com. https://en.yabiladi.com/articles/details/156093/polisario-attacks-civilians-with-projectiles.html. ↵

- Center for Preventive Action. (2024, October 23). Violent Extremism in the Sahel. Global Conflict Tracker. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violent-extremism-sahel. ↵

- Kushner, J., & Cheng, K.-C. (2024). Morocco’s War Against the Sahrawi. Pulitzer Center. https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/moroccos-war-against-sahrawi. ↵

- Center for Preventive Action. (2024, October 23). Violent Extremism in the Sahel. Global Conflict Tracker. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violent-extremism-sahel. ↵

- Center for Preventive Action. (2024, October 23). Violent Extremism in the Sahel. Global Conflict Tracker. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violent-extremism-sahel. ↵

- MINURSO. (2025). United Nations Peacekeeping. http://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/minurso. ↵

53 comments

Cris Saldana

Its kind of crazy to me that here, history repeats itself with a former colony having a colony. Just like Namibia & South Africa, Morocco & the Western Sahara (SADR) are still at it. Not only that, but the fact Morocco still refuses to recognize the Western Sahara as and independent nation, even fighting a whole war over its claim which is honestly not talked a lot about by most historians. So its nice that you’d shine a light more on this forgotten conflict. But that being said, is it possible that the Western Sahara can or will get its independence down the road?

America Rosales

What surprised me most was how deeply the Western Sahara conflict is rooted in colonial legacy and how little international attention it receives despite its severe humanitarian and geopolitical implications. I was unaware of the extent of displacement and suffering endured by the Sahrawi people, especially the fact that over 170,000 live in refugee camps under extremely harsh conditions. The aspect that resonated most with me was the resilience of the Sahrawi people and their cultural identity, maintained despite statelessness, exile, and ongoing conflict. Their oral storytelling tradition, along with their ability to adapt to new challenges like cyber warfare, demonstrates a powerful form of cultural endurance. A question on my mind is how can international media and governments be effectively pressured to prioritize and publicize the Western Sahara conflict with the same urgency as other global crises?

Carlos Flores

This article does an incredible job highlighting the deep, complex layers of the Western Sahara conflict. It ties together history, human rights, geopolitics, and even cyber warfare in a way that’s both eye-opening and urgent. The Sahrawis’ struggle deserves far more global attention, and your call for meaningful, on-the-ground engagement is both timely and absolutely necessary.

Erica Juarez

Hello Daniel,

The post effectively draws attention to the Western Sahara conflict’s long-standing neglect, highlighting the violations of human rights and the Sahrawi people’s ongoing fight for independence. The vast Moroccan-built sand wall, the second-longest in the world, shocked me by highlighting the scope of the fighting and the militarization of the area. Could you provide more details about the involvement of the international community in sustaining or ending this war, particularly with regard to support for a referendum and the implementation of UN resolutions?

Michael Ortiz

Hello Daniel,

I was surprised by how critical the phosphate resources are in Western Sahara and how central they are to the ongoing conflict. I didn’t realize how much economic interest fuels the political struggle, alongside the human rights issues facing the Sahrawi people.

The part that resonated with me most was the emphasis on how technology and cyber warfare have become new battlefields in this conflict. It really highlighted how modern security threats can intensify long-standing territorial disputes in ways that are harder to see but just as damaging.

How much influence do you think regional terrorist groups like ISGS or ISWAP could have if the conflict in Western Sahara continues unresolved?

Bella Gutierrez

Hi Daniel,

I was surprised to learn how much the Western Sahara conflict has evolved beyond traditional fighting into cyber warfare and digital threats. I hadn’t realized how much modern technology now plays a role in such a long-standing territorial dispute. What resonated most with me was the description of the Sahrawis’ statelessness and generational resilience; it showed how security is not just about borders but about basic human dignity. Do you think there’s still a realistic chance for the international community to successfully mediate this conflict after so many years of failed efforts? Great article!

Elena Petrova

Hi Daniel, I enjoyed reading your article. It is very thoroughly researched work that highlights the often-overlooked Western Sahara conflict. The discussion of the integration of cyber warfare, natural resources, and the issues of regional instability helped gain a broader understanding of the subject. Without a doubt, the region is very strategic, and many conflicting interests are involved. How might the international community build trust with local Sahrawi leaders on the ground?

Caio Ravagnani

Hello Daniel,

Great job, as always. The issue you mentioned is probably one of the most complex on the African continent, and I was intrigued to learn the root causes of it. I believe you provided a detailed overview of Western Sahara’s history and conflict with Morocco, as both claim ownership over the same region. You mentioned that Morocco has violated the human rights of Sahrawis multiple times. How can the UN and other international organizations hold the country accountable for its actions, as it seems to be tolerated?

Kimberly C Paredes

Hello Daniel,

what popped out to me was how cyberwarfare has become apart of the Western Sahara conflict. The part that resonated with me was the resilience of the Sahrawi people. Their commitment to preserve their culture and by storytelling was fascinating to me. This persistence throughout the adversity demonstrate great courage. What were the biggest challenges you faced in gathering accurate information about the Sahrawi people and their current conditions, given the media silence and political complexities surrounding Western Sahara?

Lachlan Bofinger

Dan, your article gives a compelling and well-researched historical background to the Western Sahara conflict, combining colonial histories, border conflicts, and modern security problems. The integration of cultural, historical, and geographical components gives a better insight to the reader concerning the Sahrawi people’s struggle. The incorporation of accurate data, graphs, and modern issues—i.e., cyberwar and natural resource extraction—makes this a relevant and demanding contribution to international security analysis.