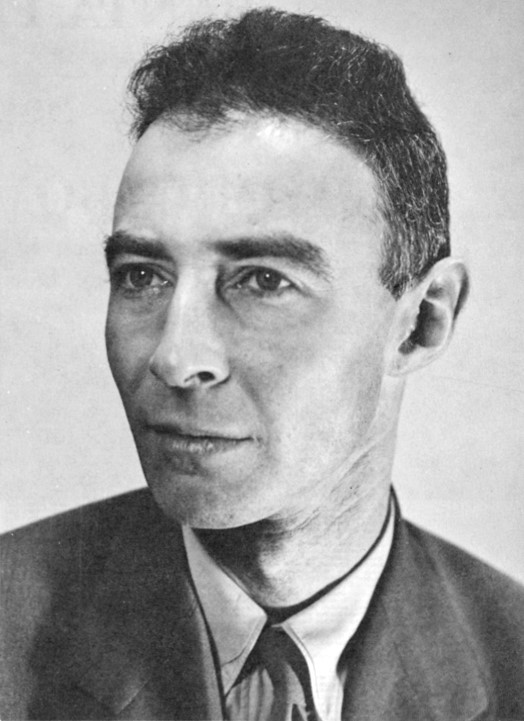

J. Robert Oppenheimer, often referred to as one of the “fathers of the atomic bomb,” was a world-renowned physicist whose discoveries and contributions made a great impact on modern physics and on history itself. However, Oppenheimer’s legacy is also clouded by the shadow of accusations of being affiliated with the communist party both during World War II and following the war during the period known as McCarthyism. But was Oppenheimer himself a communist? Few people were subject to so much surveillance in such a short period of time. Between 1942 and 1955, Oppenheimer was followed, had his phone tapped, had his mail opened, and had both his residences and offices bugged.1 Peter Goodchild wrote that some of Oppenheimer’s own statements portrayed him as being affiliated with the communist party.2 Alternatively, Ray Monk states that nothing that Oppenheimer did was subversive.3 While scholars disagree as to whether Oppenheimer was a communist or merely a sympathizer to some communist ideals who had associates that were members of the Communist Party, I argue that Oppenheimer himself was not a communist, but displayed certain sympathies to communist ideals that made him a target for accusations of being a communist.

Oppenheimer’s education in chemistry and theoretical physics started at Harvard, but he also studied at Christ’s College in Cambridge, England, and later at the University of Gottingen. Ray Monk, when writing about Oppenheimer’s time at Harvard states, “Oppenheimer’s time at Harvard was mostly spent in intense study.”4 At Cambridge, Oppenheimer made few new friends and did not make friends with any of his fellow physicists.5 Oppenheimer’s studies took him to many different countries and universities, where he associated with a diverse group of people. That diverse association certainly did not contributed to Oppenheimer associating with a particular way of thinking, and certainly not to communism in the 1920s.

Oppenheimer’s scientific work was very broad and included research into theoretical astronomy, nuclear physics, spectroscopy, and quantum field theory. He also focused on areas outside of science, including learning Sanskrit and learning about the Hindu religion. His focus on taking lessons in Sanskrit was specifically so he could read the Hindu texts in their original language.6 Oppenheimer’s interests both within science and outside of science were certainly varied but they were also not at that time political in nature.

In the 1920s, Oppenheimer did not focus on political or economic matters at all. It wasn’t until the mid-1930’s that Oppenheimer became aware of and concerned about politics. Oppenheimer’s political awakening in the 1930’s later subjected him to charges of being “un-American” and even of being a communist.7 But Oppenheimer was a sympathizer of issues, not a member of the communist party. Oppenheimer, like others, may have been viewed as aligning with the Communist Party after the Spanish Civil War began in 1936. In reality, he supported the Loyalist government that opposed the spread of fascism in Spain, ironically a role that had been left up to the Communists and to the Soviet Union, since western democratic countries were doing little to help the Loyalist cause.8 Oppenheimer was also arguably involved in a secret Communist unit, but that does not translate into Oppenheimer doing anything subversive or treasonable. As his biographer Ray Monk states, “not everything secret is subversive,” and that the group did not do anything that a group of liberals or Democrats could have done as well.9

Oppenheimer’s private and political life is an area where arguments can be made that Oppenheimer had ties to the communist party. For example, Oppenheimer supported liberal causes, like raising funds for anti-fascist activity in the Spanish Civil War, and he had relationships with people that were in the communist party, such as his own brother, Frank Oppenheimer, and with Jean Tatlock, a Berkeley graduate student with whom Oppenheimer had had a romantic relationship starting in 1936. While he did support social reforms that were in later years labeled communist ideas, he never joined the Communist Party. In fact, he financially supported German physicists fleeing Nazi Germany. Since Oppenheimer had studied in Germany in the 1920s, he was part of a group that was asked to set aside 2 to 4 percent of their income for two years to help scientists from Germany who had lost their posts. Oppenheimer wrote in March 1934, “I shall be glad to contribute to the fund and think I could promise three percent of my salary for the next two years.”10 In 1940, Oppenheimer married Katherine Harrison, who was a radical Berkeley student and former member of the Communist Party. The FBI opened a file on Oppenheimer in 1941, potentially because of his relationships with and discussions with those that were members of the Communist Party. Oppenheimer may have shared some of the same ideals as those in the Communist Party, but he was an independent thinker and focused on his work.

While Oppenheimer worked on top secret, groundbreaking work at Los Alamos, his influence hardly supports an argument that he was sharing secrets with the Soviets. Oppenheimer and General Groves understood the need for secrecy, and Oppenheimer advocated for the remote site in New Mexico for this work. “Groves and Oppenheimer, along with Kenneth Nichols and Colonel Marshall, in a conversation in a tiny compartment on a train, discussed the need for a single laboratory, preferably in a remote location away from prying eyes and ears, where the scientists working on the design and production of the atomic bomb could be gathered together.”11 Oppenheimer’s advocacy of this remote site for top secret work certainly would have made it more difficult for him to share secrets with communist spies, something that refutes arguments that Oppenheimer was trying to share secrets with the Soviet Union. There, at the place that would become Los Alamos, “the scientists could pursue their work under the watchful control and guidance of the military, sharing with each other but not with anyone else.”12

Oppenheimer’s post-war work at the Atomic Energy Commission, his controversial advocacy of international arms control, and his concerns about the hydrogen bomb may have been viewed by some as a threat to national security. On the contrary, Oppenheimer saw first-hand the risk of millions of civilian deaths through the development of a hydrogen bomb, and instead advocated for the development of fission weapons that could be targeted toward military targets. Oppenheimer advocated that a single international agency, the Atomic Development Authority, should be established. Oppenheimer’s proposal was that no nation should be allowed to build atomic bombs, and no nation would be able to build atomic bombs since his proposal would keep all the materials necessary to build a bomb in the hands of the Atomic Development Authority.13 Oppenheimer’s own views had been influenced by his own work. After witnessing the Trinity explosion, the world’s first test of an atomic explosion, Oppenheimer recalled a line from Hindu scripture that said, “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”14

Oppenheimer’s own testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee on June 7, 1949 that he had associations with those in the Communist Party during the 1930s did not help his case. When Oppenheimer was interviewed for his position at Los Alamos, and during interviews during his time at Los Alamos, Oppenheimer had stated that he knew people that were in the Communist Party. Oppenheimer himself made things worse when he did not recall making those statements.15 Many testified in support of Oppenheimer. John Lansdale, General Groves, Nobel Laureates, Enrico Fermi, Isador Rabi, and Hans Bethe, all senior figures in the United States scientific administration, all testified in support of Oppenheimer, a vote of confidence from those that had the interests of the United States first.16

In contrast to the accusations against him, Oppenheimer himself distrusted the Soviet Union. In fact, Hans Bethe, who was a scientist at Los Alamos, was surprised by Oppenheimer’s anti-Soviet views when he met with him in January of 1947. Bethe recalled conversations about the fate of the atomic energy control plan, and that Oppenheimer “had all but given up hope that the Russians would agree to a plan.”17 Bethe saw Oppenheimer as the uniting force of the scientists at Los Alamos, and that most of the scientists looked to Oppenheimer for help and guidance.18

In 1954 a security hearing was held by the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) that explored Oppenheimer’s background and his associations. It can be argued that there were those who had an agenda against Oppenheimer. Preceding his security hearing, the FBI furnished Oppenheimer’s political enemies with evidence of his Communist ties. From the beginning, motives against Oppenheimer were clear. It seemed that the prosecutor’s tactics were to say that they had evidence in the form of transcripts against Oppenheimer but were not willing to produce that evidence for Oppenheimer’s defense to see. The reason given for not sharing was that the information was classified, further casting a shadow that there may have been an agenda against Oppenheimer.19

Fears of the Soviets and the hysteria of McCarthyism further drove the accusations against Oppenheimer. Scientists, government and military figures that supported Oppenheimer at his security hearing, including Bethe, Vannevar Bush, James B. Conant, John J. McCloy, and Rabi, argued that Oppenheimer was being charged at the time of his security hearing with crimes that would not have been considered a crime at the time that Oppenheimer allegedly committed those crimes.20 It is also noteworthy to point out that trials against those suspected of spying for the Soviet Union were rarely effective, partly because espionage is extraordinarily difficult to find, but also because it is designed to leave no trace behind.21 If Oppenheimer was truly a spy for the Soviets, it seems unlikely that someone so brilliant would have openly talked about his associations with those in the Communist Party.

Finally, Oppenheimer’s view of pushing for smaller tactical nuclear weapons was at odds with those who wanted to pursue larger strategic weaponry. The FBI had no direct evidence that Oppenheimer was pro-Russian. But two of Oppenheimer’s positions were difficult to explain to some. The first was Oppenheimer’s position that the United States should give up its position as sole controlling nation of atomic weapons by creating the Atomic Development Authority. The second was Oppenheimer’s belief that no more atomic bombs should be built and that further development and tests should be stopped.22 Oppenheimer later lost this battle as the new United States Air Force won control of nuclear weapons. Oppenheimer’s security clearance was eventually stripped due to his past suspected Communist ties and suspected disloyalty to the United States.

Oppenheimer had a great impact on modern physics and on history itself through his world-renowned work in physics. And while Oppenheimer’s legacy is also clouded by the shadow of accusations of being affiliated with the communist party both during WWII and following the war during the period known as McCarthyism, Oppenheimer himself was not a communist. The Gray Board in charge of the Security hearing for Oppenheimer itself stated that Oppenheimer’s conduct was not motivated by disloyalty, making the evaluation that Oppenheimer was not a security risk.23 While J. Robert Oppenheimer was a sympathizer to some communist ideals with ties to those in the Communist Party, Oppenheimer himself was not a communist.- Peter Goodchild, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Shatterer of Worlds (Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 282. ↵

- Peter Goodchild, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Shatterer of Worlds (Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 238-241. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 248. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 83. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 95. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 205. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 238. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 239. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 248. ↵

- J. Robert Oppenheimer, Alice Kimball Smith, Charles Weiner, Robert Oppenheimer, Letters and Recollections (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1980), 25. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 337. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 337. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 499. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 430. ↵

- Peter Goodchild, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Shatterer of Worlds (Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 238-241. ↵

- Peter Goodchild, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Shatterer of Worlds (Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 246-247. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 517. ↵

- Peter Goodchild, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Shatterer of Worlds (Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 247. ↵

- Peter Goodchild, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Shatterer of Worlds (Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 244. ↵

- Peter Goodchild, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Shatterer of Worlds (Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 246-249. ↵

- John Earl Haynes, Early Cold War Spies: The Espionage Trials that Shaped American Politics (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 240. ↵

- Ray Monk, Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center (New York; Toronto: Doubleday, 2012), 506. ↵

- Peter Goodchild, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Shatterer of Worlds (Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981), 282. ↵

80 comments

Maggie Trujillo

This was an interesting article to read about Robert Oppenheimer. I don’t think I every knew that he was the father of the atomic bomb. I definitely knew about the atomic bomb and the destruction it caused, but not about Robert Oppenheimer. It is upsetting to read how bad communism was at that point in our history that they would have a security hearing on Oppenheimer just because his work was considered “classified.” After reading his article, it is very evident that his thinking and work was way ahead of his time.

Jacob Anthony Ayala

This was a very fun and interesting article to read Luis! I didn’t know much about Robert Oppenheimer before reading this article. I find it very interesting as I read more and more articles from this website that there is truly a story for every person in history. Being known as the father of the atomic bomb is truly one of the most interesting things about him. Truly one of the most brilliant minds of his time.

Veronica Lopez

Prior to this article, I haven’t heard of Robert Oppenheimer. He was an extremely interesting character. I found him to be smart because he studied in Harvard and he even got to meet Albert Einstein, one of the greatest theoretical physicist. I also loved the he was named one of the “fathers of the atomic bomb.” It shows how important his contributions were when the bomb was made till now.

Maria Jose Haile

This article was well-written with many interesting facts about Oppenheimer. To be honest, I barely had known who Robert Oppenheimer, I had the basic knowledge that he did a lot during the World War but I did not know as to what. It is interesting to realize that what I had known was false about him and he was seemingly an ordinary guy, wanting to do the right thing even though he helped begin the idea of what we know as the Atomic Bomb.

Alex Trevino

I cannot say Oppenheimer’s story is one that I was familiar with prior to reading this, however, it is very intriguing to hear about him. As his life coincides with the Cold War and the Second World War, it is very interesting that the theories surrounding his political standing were in question. The way I heard of things happening around that time, one would be taken away for conspiracy without question, so I find it remarkable that he wasn’t.

Gabriel Gonzalez

What I like most about the article is it gave us an insight to the two lives Oppenheimer lived. More specifically, private life and his political life. It also shows how high tension was in the cold war because the government suspected one America’s top scientist as being a spy. What this did is show the reality of the possession the U.S was in during the cold war which i feel is not exemplified enough.

Dominique Rodriguez

this article was very interesting to read because it gave us detail on how he created it and why he created it. the article was very informative to describing who robert was and what he did. he helped them basically win a war with a atomic bomb. i know we have atomic bombs but we havent used it becasue there hasnt been a war but its crazy to think that we have an atomic bomb that was created by robert. this article was very informative and gave so much detail i need to know about robert

Luis Molina Lucio

The creation of bombs that could destroy the whole world is hard to imagine and Oppenheimer knew that having this power specially in multiple places becomes very dangerous. Oppenheimer’s goal was to help the U.S yet he was still accused of being communist which in my eyes Oppenheimer was just being logical which the U.S because of patriotism at times throws common sense out the window. This article really informed me on who Oppenheimer was and how he helped the United States.

Carlos Hinojosa

I say the creation of the Atom bomb and all bombs that came after that was the single worst mistake in human history. Sure it brought a era of a pseudo peace but it was peace out of fear for each other’s lives, each other and what could happen to our world. Sure it was able to stop the Japanese early and prevent few more hundred thousand. But I would rather lose couple hundred thousand men more then risk the future of several billion. Some might disagree with me but that’s what I think.

Kayla Cooper

This article is very well written with so many interesting facts. Before reading this, I really did not know who Robert Oppenheimer was or what his great impact was but this article really helped me realize that he did a lot for the World War for the United States. This helps you see that communist supporter theories aren’t all that and Robert was not one.