January 1776, in a city that was not sure about what was going to be its destiny. The streets were filled with rumors, fear, and people wondering what would happen next. Sophia Rosenfeld explains that the colonies were still not focused, or at least the conversation on breaking free was still not an option. People felt fear, but it was also combined with a sense of loyalty towards the mother country. But individuals like Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine had already started thinking about independence.1 We need to keep in mind that, at this time, Philadelphia was called the “mercantile center of the British Colonies,” was one of the biggest colonies in America, at the time it had one of the busiest port in the colonies, it had a large population of artisans and craftsmen, also by being one of the largest colonies at the time it also meant that there were a lot of laborers and poor people who didn’t really know how to read. This will eventually be an important piece in the political life of Paine and Philadelphia before the Independence.2

Paine had started working with Robert Aitken, who was working on the Pennsylvania Magazine. This Magazine would later become one of the major influences in revolutionary American politics. Edward Larkin says that “it is difficult to imagine Paine writing Common Sense without the experience of editing the Pennsylvania Magazine.”3 There was a magazine called the “Gentleman’s Magazine.” This magazine was created to cater to a new social class in Britain, which most of the time was the highly educated people. In this magazine, they used really sophisticated words or phrases. Paine, on the other hand, did the opposite; he focused more on the Almanac reader. These people focused more on pseudoscientific information, such as the position of the moon, the possible weather for the year, etc. The importance of this is that the Almanac was for lower and middling readers; therefore, they used short essays on a wide range of subjects, which would eventually become a way that Paine would write Common Sense. Paine would later aim at the artisan, craftsmen, and between these, we had the poor and laborers, who most of the time didn’t really have an extensive vocabulary, and that’s when Paine’s plain style of writing came in. Paine would start to introduce his political ideas, and eventually this would make him “an active participant in Philadelphia’s political life.”4

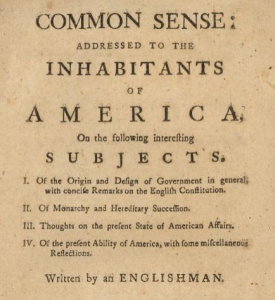

Now, Paine, knowing to whom he would be addressing his ideas and the way he would be addressing them, started drafting Common Sense. In this, he started to talk about the idea of being “self-governed,” and that America should be a republic instead of being ruled by a king or a nobility. Paine had claimed that his pamphlet had “the greatest sales performance ever seen since the use of letters.” In January 1776, Common Sense was an absolute “phenomenon.” It was said that the pamphlet sold around 100,000 copies in the first year. Independence had become the cry throughout the Colonies.5 Common Sense became “a publishing phenomenon even by the modern standards,” and it had “one of the greatest sales pitches of the late eighteenth century.”6

The pamphlet was an absolute success; it was able to reach the level of society that had never been listened to before. For example, it was read by artisans and farmers, as well as the highest level of society, ministers, and merchants. This pamphlet was considered to be the voice of the people who didn’t have a voice. This pamphlet didn’t simply argue for independence; it changed how Americans understood their own political identity, producing what Rosenfeld describes as “a change in governance and a change in their own national identities, contrary to what they thought they wanted.”7

As Paine worked during the winter, Paine wrote Common Sense, with an opening line that for many was very risky; it was a group of words that were directly confronting the need of government in these states, they were: “government even in its best state is but a necessary evil.”8 The next really famous sentence from Paine’s pamphlet is a sentence that was able to speak from the highest level of education all the way to just the ordinary people, and it was: “The cause of America is in a great measure that cause of all mankind.”8 These phrases and the pamphlet itself spread like a crazy wildfire. In the words of scholar Rosenfeld, “Soon after the appearance of Common Sense, national independence and republicanism came to seem not only viable, but also essential,” and was able to reach, “a public that ran the gamut from New England ministers to Philadelphia artisans and tradesmen.”10 This part of history is very important, people couldn’t stand the need for independence anymore, and as “their heart direction of struggle between Britain and its North American colonies.”7

The power of Common Sense came from Paine’s ability to turn outrage into clarity. He attacked monarchy and privilege in a voice that felt familiar, even though they felt intimidating. “Freedom hath been hunted round the globe,” he also wrote, “O! ye that love mankind! Ye that date oppose not only the tyranny but the tyrant, stand forth!12 He wrote this, urging readers to rise to the moment. In a matter of months, the pamphlet had done what no army could yet accomplish: it united the colonies in a common vision of independence. The man who had arrived in America weak and unknown had found his purpose in print, transforming his own ideas and morals that would eventually spark a revolutionary flame.

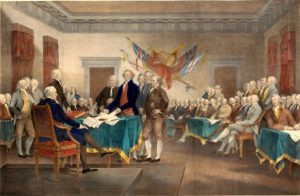

When the Continental Congress met again in June, the city was wondering what would happen. At this point, reconciliation was not an option anymore; the people were able to feel the revolution coming. Thomas Jefferson was already drafting the Declaration; his pen was drafting on Paine’s conviction and ideas. Rosenfeld explains that according to Jefferson himself, the Declaration was “the common sense of the subject,” reflecting the intellectual and moral framework that Paine’s pamphlet had helped establish.13 Even though Paine had not sat in Congress, his words were in the room. The historian Gordon S. Wood notes that both Thomas Jefferson and Paine, “believed in the right of man” and they both shared “a common outlook on the world and ideology,” making them the two most radical republicans of their age.14

Once the Declaration of Independence was signed in July, they were “free” from England; but the reality of war started to set in. From celebrating the independence to being in December, fighting for it. Washington and his army were in New Jersey fighting a really difficult battle, with heavy snow and hail. During these hard times, Paine would be using his weapon again, the pen. Paine started to compose essays, The American Crisis being one of them. This was designed to raise courage. Its first line absolutely struck the moral of all men: “These are the times that try men’s souls.”15

Paine’s sentences carried the same feeling, the same strong rhythm of words as Common Sense. He urged readers not to surrender in this difficult moment; he constantly reminded them that “the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph would be.”16 Paine’s words were again being said aloud in the campfires and in the taverns. They echoed in the streets again, just like Common Sense months before. Washington encouraged his soldiers to read Paine’s work out loud, to keep their morale up. Sophia Rosenfeld points out that Paine had some type of genius for his way of writing. She says that he spoke in “language that was by turns unadorned, satirical, prophetic, metaphoric, and violently indignant.”17 Paine’s “plain truth” became a language of empowerment that helped common people see themselves as participants; therefore, during this time of war, this was important, so people could have sympathy towards the soldiers, and this helped the soldiers keep their morale up.

Thomas Paine never led an army like Washington, and never held an office, yet his words carried the weight of both his courage and conviction. Through Common Sense and The American Crisis, he gave ordinary people the chance to feel included, to feel freedom, and to understand their natural rights. His simple, plain language was able to turn political arguments into a moral purpose. Maybe his later years brought him isolation, but his ideas are still part of U.S. history. Even now, people still look back at Paine as a hero, thanks to his words of courage, trying to demand equality and justice. Paine’s revolution didn’t end in 1776. It lives on wherever people who challenged oppression with truth and reason are. He believed that we have to fight for what is ours, in this case, democracy. Thomas Paine gave America more than independence. He gave it a voice.

- Sophia Rosenfeld, “Tom Paine’s Common Sense and Ours,” The William and Mary Quarterly 65, no. 4 (October 2008): 636. ↵

- Edward Larkin, “Inventing an American Public: Thomas Paine, the Pennsylvania Magazine, and American Revolutionary Discourse,” Early American Literature 33, no. 3 (1998): 259. ↵

- Edward Larkin, “Inventing an American Public: Thomas Paine, the Pennsylvania Magazine, and American Revolutionary Discourse,” Early American Literature 33, no. 3 (1998): 253. ↵

- Edward Larkin, “Inventing an American Public: Thomas Paine, the Pennsylvania Magazine, and American Revolutionary Discourse,” Early American Literature 33, no. 3 (1998): 258-259. ↵

- Sophia Rosenfeld, “Tom Paine’s Common Sense and Ours,” The William and Mary Quarterly 65, no. 4 (October 2008): 636-637. ↵

- Sophia Rosenfeld, “Tom Paine’s Common Sense and Ours,” The William and Mary Quarterly 65, no. 4 (October 2008): 637. ↵

- Sophia Rosenfeld, “Tom Paine’s Common Sense and Ours,” The William and Mary Quarterly 65, no. 4 (October 2008): 638. ↵

- Thomas Paine, Common Sense (Philadelphia: R. Bell, 1776): 1. ↵

- Thomas Paine, Common Sense (Philadelphia: R. Bell, 1776): 1. ↵

- Sophia Rosenfeld, “Tom Paine’s Common Sense and Ours,” The William and Mary Quarterly 65, no. 4 (October 2008): 637-638. ↵

- Sophia Rosenfeld, “Tom Paine’s Common Sense and Ours,” The William and Mary Quarterly 65, no. 4 (October 2008): 638. ↵

- Thomas Paine, Common Sense (Philadelphia: R. Bell, 1776): 17. ↵

- Sophia Rosenfeld, “Tom Paine’s Common Sense and Ours,” The William and Mary Quarterly 65, no. 4 (October 2008): 662. ↵

- Gordon S. Wood, “Introduction,” in Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions, ed. Simon P. Newman and Peter S. Onuf (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 14. ↵

- Thomas Paine, The American Crisis, #1, December 1776, 1. ↵

- Thomas Paine, The American Crisis, #1, December 1776, 1. ↵

- Sophia Rosenfeld, “Tom Paine’s Common Sense and Ours,” The William and Mary Quarterly 65, no. 4 (October 2008), 646. ↵