It was 6:50 p.m. on Friday, August 14, 1970, and a warrant was issued by Marin County Superior Court Judge Peter Allen Smith for the arrest of Angela Yvonne Davis, an African-American Communist, scholar, and activist who advocated for prisoners’ rights. Angela Davis was charged with aggravated kidnapping and first degree murder of Superior Court Judge in Marin County, California, Harold Haley.1

There was an attack on the black prisoners at Soledad Prison in California by white prisoners, and shots were fired by Officer O.G. Miller, killing three black prisoners. And subsequently Officer Miller was exonerated. After news reached Soledad Prison that the grand jury ruled Miller’s case as a “justifiable homicide,” Officer John Y. Mills was found dying in “Y” wing of the prison, and three prisoners known as the Soledad Brothers (George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo, and John Clutchette) were indicted for the murder. On August 7, during the trial of James McClain (a prisoner at San Quentin State Prison accused of attempted assault of a guard), the younger brother of Soledad Brother George Jackson— Jonathan Jackson, armed McClain and two other San Quentin prisoners. They took Judge Haley, Deputy District Attorney Gary Thomas, and three jurors hostage, in a plan to escape. Jackson, McClain, Haley, and another prisoner were killed in the attempted escape, Haley being killed by a shotgun that was tied to his neck. The guns used in this attempted escape were purchased in the name of Angela Davis, and so she was charged as a principal in the crimes.2

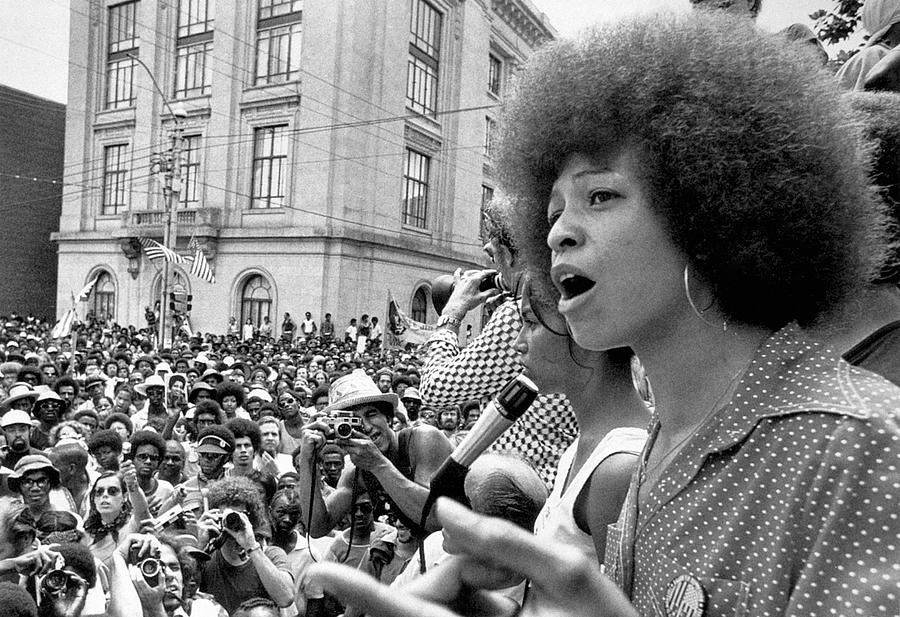

Angela Davis was a profound political activist and public figure, as she was affiliated with the Black Panther Party, a part of the Che-Lumumba Club (an all-black branch of the Communist party), and the co-chairperson of the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee in Southern California.3 The events that happened on August 7th were considered to be an alleged attempt to free the Soledad Brothers, and officials targeted Angela Davis in order to take down the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee, the Black Liberation of Movement, and the Communist Party.4

Angela Davis “WANTED” poster. | Courtesy of The Guardian

Angela Davis then went on the run. Searching and raiding the San Francisco headquarters of the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee and arresting and releasing Davis’ sister, authorities could not seem to locate Angela Davis. On August 15, a warrant for the arrest of Davis for interstate flight to avoid prosecution for murder and kidnapping was issued by the FBI, and on the 18th she was placed on the list of “Ten Most Wanted” criminals. The wanted poster for Angela Davis characterized her as “wanted and dangerous.” There were many rumors regarding the location of Davis, and many people throughout the black community were detained and questioned, especially young women with afros. On October 13, Angela Davis was found and arrested by FBI special agents in New York City, and President Richard Nixon immediately congratulated FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover for the capture of “dangerous terrorist” Angela Davis on national television.5

The United States has a history of portraying African Americans as dangerous criminals, and this tactic has been used by politicians and media ever since the Reconstruction era. Following the end of the Civil War and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, there arose a mythology of black criminality, especially as black men were being portrayed as “out of control,” and “threats to white women.” In 1915, with the release of D.W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation, there arose a nationwide fear of the black man. White men covered in blackface acted as black men and terrorized, raped, and acted as dangerous animalistic criminals in the film. The Birth of a Nation was praised and immensely popular throughout the United States, as it represented the narrative that many white people wanted to tell about the Civil War and its consequences. Not only did the film portray black men as out of control, but it portrayed the Ku Klux Klan as heroic and brave, which ultimately led to the regrowth of the white supremacist hate group. In the midst of the Jim Crow era, which kept African Americans in a second class status through de jure segregation laws, black people were criminalized for simply fighting for their rights. Many Civil Rights leaders, such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, were arrested for peaceful protests against oppression.6 This overrepresentation of black people as criminal and the over-presentation of black suspects that assumes their guilt has fed stereotypes and prejudice surrounding African Americans that has led to a nationwide subconscious perception of what a criminal looks like.7

On December 22, Davis was awakened from her sleep at the New York Women’s House of Detention and was told that her lawyers wanted to see her. Instead of meeting her lawyers, she was bombarded by four police officers, slammed to the ground, handcuffed, and thrown into a police car that took her to an Air Force base in New Jersey. She was flown to Marin County, and driven to Marin County Jail where she was booked for first degree murder, kidnapping, and conspiracy (a new count), with no bail.8

On January 5, 1971, Angela Davis appeared in Marin County Superior Court alongside her co-defendant Ruchell Magee (a political prisoner at San Quentin), and said,

“I [Angela Yvonne Davis] now declare publicly before the court, before the people of this country that I am innocent of all charges which have been leveled against me by the State of California. I am innocent and therefore maintain that my presence in this courtroom is unrelated to any criminal act.

I stand before this court as a target of political frame up which far from pointing to my culpability implicates the State of California as an agent of political repression.”9

After a long and hard fight for bail and a fair trial, Angela Davis was finally granted bail in the sum of $102,500 on February 23, 1972. Her team immediately got the money together, thanks to Rodger McAfee, and they had Davis out in a few hours, and at 7:14 p.m. she walked free, with her fist in the air, as a crowd of people cheered and roared.10 Thousands of people across the world had been backing Davis, knowing she was innocent. The movement to free Angela Davis began with Franklin Alexander of the Communist Party, as he established the National United Committee to Free Angela Davis.11 She had received so much support in her fight for bail, including legendary musicians, such as John Lennon, and the Rolling Stones, who wrote songs about her.

In the early 1970s, there was a shift in public opinion regarding the United States’ prison system. In 1971, a group known as the Attica Liberation Faction at Attica Correctional Facility, a State prison in Attica, New York, presented a list of demands to Russell Oswald, the state prison chief, regarding the inhumane conditions taking place in the prison. The prisoners at Attica were enduring terrible living conditions, overcrowding, poor medical treatment, brutality from guards, and forced labor. The inmates were at their breaking point. Many of them were black militants, being a part of the Black Panther Party or The Weather Underground Organization, and they came together, conducting political education classes on the yard to promote social change. On September 9, 1971, inmates found themselves trapped in a tunnel leading to the yard, and feeling that the trap was purposeful and that guards were about to attack them, they broke down the door and took over the prison. A revolution within the prison was happening, with a designated group holding employees hostage, organizing security forces, and establishing allies/witnesses on the outside. Initially, officials were open to negotiation, but Richard Nixon and the FBI pushed New York’s Governor to end the rebellion without negotiation. Four days later, troops raided the prison and killed 39 people. 43 people died. The riot at Attica received more media attention than any other event highlighting the struggles of prisoners, and sparked a nationwide conversation regarding the details of prison conditions.12 The riot at Attica is the root of the prison reform movement in the United States, as it exhibited the inhumane treatment of inmates within prisons, based on the demands and dialogue of the inmates.

It was time for Angela Davis to prepare for trial.

Following the trial of the Soledad Brothers (who were acquitted on all counts), Angela Davis made the opening statement for the defense in her trial.

“Members of the jury, we were correct in our understanding of the case of the Soledad Brothers. Monday morning as you sat there listening to the prosecution’s opening statement… the ultimate fruits of our labors were attained. The 12 men and women who for a period of many months had listened to all the evidence which the prosecution could muster against the Brothers, entered a courtroom in San Francisco and pronounced the Soledad Brothers NOT GUILTY. If George Jackson had not been struck down by San Quentin guards in August of last year he too would have been freed from that unjust prosecution…”13

The prosecution’s case against Davis was based on motive. Prosecutor Albert Harris had to build a case against her that showed that she had reason to participate in this alleged plot to free the Soledad Brothers. His initial plan was to use her political extremism and her relationship with George Jackson, both supplied with evidence, against her in a way that gave her motive to commit those crimes. However, with the shift in political viewpoints of citizens throughout the country regarding the awareness of the racism and cruelty within the prison system, Harris decided to focus his case against her on the relationship she had with George Jackson, in which he contained the letters she wrote to him, along with her diary, as evidence. Harris claimed that she was not a political prisoner, and that “her basic motive was not to free political prisoners, but to free the one prisoner she loved… [the motive] was not founded… for prison reform. It was founded simply on the passion that she felt for George Jackson…”14

All of the jurors at Angela Davis’ trial were white. The jury selection process had been lengthy, as Davis and her team came across many prospective jurors with different perspectives regarding Angela Davis, politics, and the prison system— some wanting no conflict, some having family ties to police and armed forces, some fearful of serving on this particular jury, some despising Communists, a few liking the ideals of Communism, some professing that they could not be fair at this trial, and many having had no contact with black people.15 On March 14th, the jury was finally accepted. Angela stood before the court and said,

“We have long contended Judge Arnason, that it would be virtually impossible for me to receive a fair trial in Santa Clara County. As you know, we have made a number of change of venue motions challenging the ruling that the case be tried in this county. As I look at the present jury I see that the women and men do reflect the composition of this county. There are no black people sitting on the jury. Although I cannot say that this is a jury of peers, I can say that, after much discussion, we have reached the conclusion that the women and men sitting on the jury will put forth their best efforts to give me a fair trial. I do not think that further delay in the jury selection process will affect in any way the composition of the jury, and because we have confidence in the women and men presently sitting in the jury box, I am happy to say that we accept this jury.”16

Albert Harris presented his case against Angela Davis in three different parts. The first was presenting his version of what happened on August 7. He called 39 witnesses to depict what happened that day. He needed to show that Davis was involved in a plan (conspiracy) to free the Soledad Brothers, that with this plan the three San Quentin prisoners kidnapped Judge Haley, assistant district attorney Gary Thomas, and the three jurors, and that Judge Haley was killed during this kidnapping. The most critical witnesses that Harris called were Maria Graham, a juror that was kidnapped and wounded on August 7, James Kean, a reporter and friend of Judge Haley, Captain Harvey Teague of Marin County’s Sherriff’s Department, and Gary Thomas. Each of them testified that they heard specific indications of a plan in place to free the Soledad Brothers. Gary Thomas testified that he saw Ruchell Magee shoot Haley in the face with the shotgun. Harris presented the guns, some books containing Angela Davis’ signature, clothes, photographs, and Jonathan Jackson’s wallet as evidence.17

The next part of Harris’ case focused on Angela Davis’ passion for George Jackson, giving her motivation to be involved. He sought to use Davis’ letters to Jackson, along with her diary, as evidence. Judge Arnason suppressed the use of the diary, which Harris claimed was the heart of his case. Harris read the letters, which expressed Davis’ love for Jackson.18

In the third part of his case, Harris called 43 witnesses to display Angela Davis’ alleged role in the conspiracy. His witnesses testified that Angela Davis had purchased firearms and ammunition and cashed multiple checks, alongside Jonathan Jackson, and that they had been seen at San Quentin prison together on August 5. The young woman alongside Jackson was in fact Diane Robinson, not Angela Davis. Alden Fleming, the Mobil Gas Station owner from which Jackson placed a phone call, testified that he remembered Jackson and that he was accompanied by a “colored girl” whom he identified as Angela Davis. Louis Y. White, a former San Quentin prisoner, testified that he saw Jackson and Angela Davis leaving the San Quentin parking lot in a yellow van. In actuality, Jackson was alone. He also testified that on August 5 he saw them in the van. The van hadn’t been rented until August 6. Based on a telephone number found in Jonathan Jackson’s wallet and a claim from Marcia Lynn Brewer (an airline ticket agent) that Angela Davis was at San Francisco International Airport around 2 p.m. on August 7, Harris had a theory that Angela Davis had been waiting at a phone booth by the airport for a call from Jackson.19

Albert Harris expressed to Judge Arnason that the diary was critical to his case. Two weeks later the judge presented a new version of the diary, which precluded any legally unacceptable material. Harris read the diary, which expressed Angela Davis’ love for George Jackson on a much deeper, vulnerable, and intimate level than the letters. Harris rested his case.20

The defense of Angela Davis understood that Harris’ case was extremely inferential. His case caused confusion in the courtroom; their credibility was negligible and did not prove that there was a plan in place to free the Soledad Brothers. Everything that Harris’ witnesses testified to regarding Davis’ whereabouts were unreliable, and the letters and diary contained nothing incriminating. The defense presented a “pin-point defense,” in which they would attack Harris’ strongest links.21

The defense called twelve witnesses, who were able to refute the testimonies of the witnesses that put Angela Davis and Jonathan Jackson together on August 4th, 5th, and 6th. They were also able to justify Davis’ ownership of the firearms, Jackson’s access to them, and her purchase of the shotgun.22 One of the witnesses called was Soledad Brother Fleeta Drumgo. He entered the courtroom from the basement holding cell, shackled and chained at the feet, waist, and left arm. Fleeta Drumgo said that he knew nothing of a plan to escape and free himself and his fellow Soledad Brothers.23

In the closing argument of the defense, Leo Branton Jr., Angela Davis’ defense attorney, depicted the black American experience to the jury, and made them understand the love that Angela Davis had for George Jackson with regard to her devotion to black people, all while exposing the prosecution’s racist slurs and sexual insinuations. Harris then made his rebuttal and the trial came to a close.24

On Sunday, June 4, the jury had a verdict.25

In the jury trial stage of a criminal case, the judge provides the jury with specific instructions, going over the rules that the jury has to implement in their deliberations. Once the jury is in the jury room, they elect a foreman, a head juror who facilitates the deliberation. Many times the foreman takes a quick poll in order to indicate how close the jury is to an agreement. This gives them an idea of what they need to discuss and consider. If the initial vote is unanimous or close to unanimous, deliberations can be extremely short. If the initial vote is not unanimous, jury deliberations can take days, or even weeks if the jury is evenly split, or if there happens to be one juror who will not agree with the other eleven. If the jury is unable to reach a unanimous decision, the foreman reports to the judge that the jury is deadlocked, also called a hung jury, resulting in a mistrial. If the jury reaches a unanimous decision, the foreman reports to the judge that they have a verdict.26

Judge Arnason: Ms. Timothy, has the jury reached a verdict?

Ms. Timothy: Yes, your honor. We have.

The clerk:

In the case of The People of the State of California vs. Angela Y. Davis, Case Number 52613… Kidnapping in the first degree… The jury finds the defendant Angela Y. Davis, Not Guilty.

…Murder in the first degree… The jury finds the defendant… Not Guilty.

In the case of the People…vs. Angela Y. Davis… Conspiracy. The jury finds the defendant…

Not Guilty.27

Angela Davis had been acquitted of all counts by an all-white jury. Cheers and roars filled the courtroom. Angela Davis was sobbing and embracing her loved ones. Angela said,

“This is the happiest day of my life… People all across the country and the world who worked for my freedoms see this as an example of things to come. From this day forward we must work to free every political prisoner and oppressed people everywhere.”28

A crowd at a nearby rally began to chant, “POWER OF THE PEOPLE SET ANGELA FREE!”29

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 21. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 5-6. ↵

- Jone Johnson Lewis, “Biography of Angela Davis, Political Activist and Academic,” Thought Co., May 24, 2019, https://www.thoughtco.com/angela-davis-biography-3528285. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis(Cornell University Press, 1997), 20. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 22-24. ↵

- Ava Duvernay, “13th,” 2016, Netflix. ↵

- Mary Beth Oliver, “African American Men as ‘Criminal and Dangerous’: Implications of Media Portrayals of Crime on the ‘Criminalization’ of African American Men,” Journal of African American Studies 7, no. 2 (2003): 3-18. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 25-26. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 6. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 145-153. ↵

- Sol Stern, “The Campaign to Free Angela Davis… and Mitchell Magee,” The New York Times, June 27, 1971, https://www.nytimes.com/1971/06/27/archives/the-campaign-to-free-angela-davis-and-ruchell-magee-the-campaign-to.html. ↵

- “The Story of the Attica Riot That Changed American Prison Conditions,” Medium, September 10, 2016, https://timeline.com/attica-riot-prison-conditions-fbfdf96620f9. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis(Cornell University Press, 1997), 164. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 165-166. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 168-180. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis(Cornell University Press, 1997), 181. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 185-200. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 200-216. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 216-233. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 233-240. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 240-244. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 244. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 265-257. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 244-266. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 271. ↵

- Charles Montado, “The Jury Trial Stage of a Criminal Case,” Thought Co., September 27, 2019, https://www.thoughtco.com/the-trial-stage-970834. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 273. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis(Cornell University Press, 1997), 274. ↵

- Bettina Aptheker, The Morning Breaks: The Trial of Angela Davis (Cornell University Press, 1997), 275. ↵

52 comments

Kathryn Martinez

Before reading this article I had never heard about Angela Davis. Based on this article I have learned that she was a remarkable woman who stood up for her people and her beliefs. Yet again this article reminds me that not long ago people of color would have to fight every day just to not be convicted for things they have done and that there are still people that are serving sentences for things they didn’t commit. I truly hope that one day people of color will not have to worry about these issues.

Wilzave Quiles Guzman

Congratulations! This article has very clear details and it is very organized. Honestly, I have always known and read about civil rights movements involving peaceful demonstrations. This was my first time reading about a no-peaceful demonstration related to the civil rights movement. It is interesting for me that almost every time in history in which a change is made is because of oppression and injustices that occurred. So when oppression arises, people, find a purpose to produce a revolution for the common good. In this case, the trial of “The people vs. Angela Davis” ignited the support of everyone in having better conditions in prisons and assuring the rights of people when being on trial.

Dr Celine

What an inspirational story and you did have me on the edge of my seat waiting for the verdict to come back. You have a real talent for building suspense and telling a truly compelling story by selecting important details. Quite a triumph to have been exonerated despite so many elements that seem to tip the scale in favor of the prosecution. Certainly jury selection and statement in acknowledging her life was in their hands. The images you used at the end of coming back to speak on the UCLA campus from where she had been sacked is empowering.

Amanda Quiroz

This time is so sad to me. I have never heard of Angela Davis but after reading this article, I admire her for standing strong and fighting for what she believed in. I personally never understood why people would label others based on the foundation of their skin. Great job of how explaining how people of color were portrayed during the time.

Kelsey Sanchez

I have never heard about the story behind Angela Davis. I really found this article interesting to read due to it showing how Angela managed to prove to the court that she was not guilty of all the things that had occurred. I really can’t believe why people of white always assume that people of color are criminals and make them be treated poorly. I was shocked by the way president Nixon had congratulated the FBI for the job they had done to search for her. However, I am glad Angela did not show any fear and she stood up for her innocence, which she was all along. She was an absolute role model for many women. Great article!

Raul Vallejo

Very inspiring to read about the way that Angela Davis was able to overcome adversity and manage to overcome all odds and still be proven innocent in a trial that had an all white jury. She was accused of everything that she did because of her race and managed to overcome many stereotypes. She is an icon.

Kasandra Ramirez Ferrer

I find ridiculous how white people discriminate and say that people of color are criminals and dangerous. I did not know who Angela David was but I am glad to be aware of all the things she did and recognize that Angela stood up for she believed in and not be afraid of the judgment of others. Angelas is one of the women who are responsible for the progress of women in society.

Thalia Romo

This article was well written, and I agree with your point where you say, “The United States has a history of portraying African Americans as dangerous criminals, and this tactic has been used by politicians and media ever since the Reconstruction era.” It’s scary with how aggressive police officers were with individuals of a different race. The tactics that the prosecution possessed were most likely praised by other individual’s, however they’re seen as dirty to me.

Addie Piatz

I did not know about Angela Davis until reading this but I am so glad that I do now. I love reading and learning about strong women who stand up for themselves and what they believe in. I hate that she was seen as dangerous simply because of the color of her skin. I think it is amazing that she was supported but many famous artists.

Victoria Davis

I have no previous knowledge about Angela Davis, but this was a well informative article. Angela never let the color of her skin affect what others had to say about her. She always seemed to push forward and fought for what she saw in her eyes to be right. The praise she got from famous people I felt gave great support and showed that anyone can raise about white supremacy.