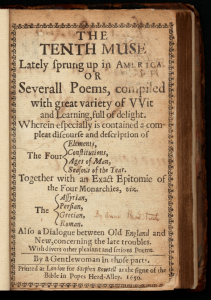

The Bradstreet family lived in several locations after arriving in America, first in Newtowne, which is now Cambridge, Massachusetts, then in Ipswich, before finally settling in what is now North Andover. Life was difficult for the family, and they faced many hardships, but it was Anne’s strong faith that helped her endure, even though she often struggled with some of the tougher aspects of Puritan beliefs, such as concepts of salvation and redemption. From a young age, Anne’s health was fragile. Once the family was settled in Massachusetts, she eagerly awaited the arrival of children. Between the years 1633 and 1652, she gave birth to eight children, which made her domestic life incredibly demanding. Despite these responsibilities, she continued to write poetry, showing a deep commitment to the craft of writing. Her work not only reflects her dedication to writing, but also the religious and emotional conflicts she faced as both a woman and a Puritan. In 1650, less than fifteen years after arriving in America, Anne Bradstreet made history by becoming the first colonial settler and the first woman to ever publish a book of poetry in England. Her book, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America, displayed an intellectual equal to that of other notable thinkers like Anne Hutchinson, covering complex subjects that were often thought too difficult for women to grasp. Bradstreet wrote extensively on the topics of history, science, anatomy, physiology, Greek philosophy, theology, and family life. While her poems were often lengthy, instructional, and at times awkward, they challenged the prevailing seventeenth-century views on women. Through her work, she confronted the expectations of her time, and The Tenth Muse became widely popular, gaining recognition on both sides of the Atlantic. As biographer Charlotte Gordon notes, Bradstreet’s words “would catch fire,” making her the voice of an era and an aspiration for a new century.1

Anne Bradstreet was one of the few women in the seventeenth century who was a privileged English woman who was transplanted in her late teens to Massachusetts and spent the rest of her life outside England and to have been fortunate enough to receive a good education. The parents of these few women were deeply supportive of their daughters’ education and poetic ambitions. They provided access to libraries and funded tutors, ensuring their daughters had the resources needed to develop their intellectual abilities.2 While it was uncommon for women to attend formal school during this time, they still received educations that were suited to their social standing. For women of Anne Bradstreet’s generation and social class, this education was meaningful and substantial.3 Bradstreet’s father, Thomas Dudley, was educated at Cambridge and worked as a steward for the English aristocracy, managing estates of Theophilus Fiennes-Clinton, and the fourth Earl of Lincoln. As for her mother, Dorothy Dudley was actively involved in her family’s life and served as a strong example for Anne on how to balance being a wife, mother, Christian, teacher, and writer.4 Bradstreet was raised in a household where learning was highly valued, and her family encouraged her to read and broaden her understanding of literature after emigrating to the American colonies in 1630. Anne Bradstreet spent most of her early years, from age eleven until her marriage at sixteen, at the Earl of Lincoln’s Sempringham estate. While living there, she had access to the earl’s large library, her father’s knowledgeable guidance, and the education provided by tutors for the earl’s sibling.5 In other words, Anne Bradstreet belonged to the service class of the elite, yet she lived among the upper class, both in England and in Massachusetts Bay.6 Therefore, Anne began to absorb her parents’ lessons and applied her family’s values and beliefs into her own understanding of life, developing a passion for writing.

Anne Bradstreet’s life reflects a common pattern among young women in Puritan households, where serious study was given to subjects like history, literature, and language, alongside scripture and religion. These young women not only focused on religious education, but also engaged deeply with intellectual pursuits, producing literary work in these areas. In this way, she followed a tradition of Puritan women who balanced their religious duties with a strong commitment to learning and literary creation, contributing to both spiritual and intellectual life.7 Some young women, like Joceline and Lucky Hutchinson, openly rejected their earlier “secular” interests, choosing instead to focus on more traditional roles. Others may have had to give up these interests because of the demands of raising children and managing a household. This was not unique to women, as many men also set aside their artistic pursuits to take on adult responsibilities. What makes Anne Bradstreet stand out is that she had her poems published at a time when most writers, both male and female, did not have that opportunity. In fact, much of what these women wrote has been lost to history – not because they were discouraged from writing or seen as unimportant as writers, but because of the social and cultural circumstances surrounding literary production in the seventeenth century.8 In a time when women were subordinated to men, and men were subordinated to God, women who stepped outside their traditional domestic roles through literature – whether by reading or writing – were often seen as a threat to both themselves and society. The Puritans, in particular, showed strong disapproval toward women who wrote or published their work. For Anne Bradstreet, one of the biggest challenges in writing her quaternions was advocating for values that were considered feminine in a society that rejected female independence. To assert herself as both a woman and a writer, she had to experience a kind of inner conflict, since her culture strongly discouraged women from affirming their own identities. In Puritan belief, the ideal was a person to focus less on themselves, and the best path was to avoid self-reflection altogether, to essentially disappear. Bradstreet navigates this tension between self-assertion and the cultural prohibition against it through the techniques she uses in her quaternions. By creating this kind of staged conflict, she formed a literary expression of integration – a way to assert her identity and her place in the world, especially as a Puritan woman daring to write, despite the cultural forces that sought to deny her the right to do so.9 Therefore, at the time, there were fewer chances for women to publish their work, and the records of their literary efforts were often overlooked and erased.

The extent to which individual Puritans placed their hopes on being counted among the elect cannot be overstated.10 For Puritans, the quest for salvation was both a personal and shared journey that affected every aspect of their lives. They engaged in a continual and exacting process of self-examination, interpreting every personal experience and national event as either a sign of divine favor or a warning of their spiritual standing. The Puritans believed that grace had to be actively pursued and earned, so they looked at even the smallest events in their lives through a religious perspective. For instance, Anne Bradstreet, at the age of fourteen, developed strong feelings for her father’s assistant, Simon Bradstreet.11 Simon Bradstreet was a Cambridge-educated man who, like her father, worked as a steward for the English aristocracy before moving to Massachusetts Bay.12 These feelings troubled her deeply, as Puritan teachings considered them sinful unless they were expressed within the confines of marriage. Anne thought that her feelings were sinful, so she prayed hard seeking deliverance from what she viewed as carnal lust. Her emotional struggle was not only a personal crisis but also a spiritual one, as she feared that these temptations might threaten her chances of being counted among the elect. In 1626, Anne fell ill with smallpox, a highly feared and often deadly disease. She saw her illness as divine punishment for her perceived sin, viewing it as a punishment for her impure thoughts and feelings. This view of illness as a sign of God’s disapproval was common among Puritans, who believed that both physical and spiritual suffering were signs of God’s will. In Anne Bradstreet’s short poem ‘To My Dear and Loving Husband,’ Bradstreet confidently asserts that if the fundamental human paradox is true – that love can truly unite two distinct individuals – then she and her husband have achieved a perfectly balanced union. Her husband, Simon Bradstreet, seemed to fully support her literary ambitions, and she also expressed deep affection for him in this short poem.13 The poem begins with the lines: “If ever two were one, then surely we. If ever man were lov’d by wife, then thee; If ever wife was happy in a man, Compare me with ye women if you can,” where Anne wrote that she loves her husband as deeply as he loves her, with their affection for each other in perfect balance, forming a bond of mutual devotion and equality.14

Anne Bradstreet’s brother-in-law, John Woodbridge, was responsible for publishing the first edition of The Tenth Muse.15 At the time of his departure from Massachusetts, he decided to bring the manuscript along, and it was through his efforts that Anne Bradstreet’s work was eventually published. It is unclear whether The Tenth Muse preserves the original order of the poems in the papers that Woodbridge took with him. We do not know if the poems were in Anne Bradstreet’s own handwriting or if they were transcribed by someone else. It remains uncertain whether Bradstreet had a single, organized manuscript or a disordered collection of papers, which makes it difficult to fully understand the original work that Woodbridge brought back with him.16 We do know that Anne Bradstreet did not choose the title The Tenth Muse. Many critics have discussed how calling her “The Tenth Muse” both limits and simplifies her, placing her in a traditional, feminine role. However, as Wright points out, the title page also highlights Bradstreet’s knowledge, as seen in the political themes present in many of her poems in the collection.17 In 1648, when Bradstreet’s manuscript of “publick” poems was circulating among family members, certain people had come across bits and pieces of the manuscript. Some of these individuals seemed eager to publish them, even though Bradstreet had never intended for them to be released. Concerned that these “broken pieces” might be published and harm Bradstreet’s reputation, Woodbridge decided to take matters into his own hands. He gathered the scattered poems together and had them published without Bradstreet’s involvement or consent. In the preface of The Tenth Muse, Woodbridge included a defense of the work, anticipating the skepticism he believed readers would have towards poems written by a woman. He feared that the publication of such poems would provoke doubt about their authenticity, and that readers might question whether a woman could produce such writing.18 To address this, he added eleven verse tributes, all written by male figures, to validate the poems’ legitimacy and reassure readers. These tributes were meant to challenge the belief that a woman’s work could not be taken seriously. Additionally, the volume was prefaced with praise for Bradstreet from figures like Nathaniel Ward, author of The Simple Cobler of Aggawam (1647), and Reverend Benjamin Woodbridge, John Woodbridge’s brother.19 These praises were included to protect Bradstreet from potential criticism, both at home and abroad, that might arise from the belief that it was improper for a woman to be an author. They emphasized her virtue and moral character, seeking to assure readers that she was a respectable woman worthy of recognition.20

To understand Anne Bradstreet as a poet, we must set aside our modern obsession with print publication. Much of this emphasis comes from a post-Romantic belief that anyone who writes poetry views themselves as a “poet,” that print publication confirms their identity, and that success is measured by public recognition and widespread fame. However, in the early modern period, being a “professional” artist meant having to sell one’s art to make a living. Publishing a collection of poems was typically a way to gain sponsorship or secure employment, not an effort to achieve fame or recognition. Anne Bradstreet, however, was not seeking work as her motivations were different from those of the professional writers of her time.21 We can no longer describe Anne Bradstreet as “a woman in the male-dominated field of professional writing,” nor can we suggest that she ever wanted to be a “professional” poet, seeking commercial recognition for her work. There is no evidence to support the idea that Bradstreet consciously chose to enter the world of print or that she was pleased after the fact to have her poems published. There is no indication that once her work was in print, she simply accepted it or planned for a new edition of her work. In fact, all the evidence suggests the opposite, that her involvement in print publication was not something she had actively chosen or embraced.22 While the publication of these personal poems may have “publicized the supposedly private experiences of a woman,” it is important to note that it was the editors who made the decision to publish them, not Bradstreet herself. Therefore, we should not suggest that Bradstreet intended that these personal poems would be made public. In “The Author to Her Book,” it clearly shows that Bradstreet was distressed to see her first published poem The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America in print. It is misguided for us to assume that the social anxieties and anger she expressed in the poem come from being known as a writer. The poem reflects her discomfort with having her private thoughts exposed to the public, rather than frustration with being recognized as an author.23 If we examine Bradstreet’s short poem “The Author to Her Book” further, we begin to understand the difficulties women faced in claiming their own authority and voices in a Puritan society dominated by men. Whether criticized or appropriated, women had to fight for legitimacy with the only tools available to them: the written and spoken word.24 Recent biographers of Bradstreet, Elizabeth Wade White and Ann Stanford, have pointed out that she often struggled with the conflicting demands of piety and poetry. She was determined to be bold as possible in expressing herself, but she had to do so within the boundaries of a society that valued respectability and had exiled Anne Hutchinson for challenging its norms. Bradstreet’s poetry reflects the tension of a woman who wanted to assert her individuality in a culture that was resistant to personal freedom and expression. In this society, poetry was only valued if it praised God, so Bradstreet had to navigate these restrictions, striving to make her voice heard while adhering to the expectations of her time.25

Anne’s background, coming from a wealthy family and receiving a solid, though informal education, gave her significant advantages in a time when many colonial women were not even taught how to read, much less write.26 In an era where women’s educational opportunities were limited, especially in the colonies, Anne’s access to learning set her apart. Her family’s wealth allowed her the resources to pursue education, even if it wasn’t formal or structured like that of many men. This privilege helped her shape her intellectual abilities and provided her with the tools to write, allowing her to engage with literature in a way that most women of her time could not. Despite facing a great deal of criticism and the many challenges that came with being a woman writer in her time, Anne Bradstreet produced an impressive and extensive body of poetry. Throughout her work, she boldly rejected the widespread belief that women were inferior to men.27 Anne Bradstreet effectively resisted the societal limitations placed on women’s voices, which were clearly illustrated by the banishment of Anne Hutchinson, by expressing her views on Puritan theology in the form of a poetic love letter to her husband. This allowed her to engage with complex theological topics while still adhering to the expectations of her role as a Puritan woman. Through this approach, she was able to assert her intellectual and spiritual beliefs without stepping outside the boundaries imposed on women’s speech.28 Anne Bradstreet’s poetry has earned widespread admiration and recognition for more than three centuries. Through her remarkable talent and unique voice, she has firmly established herself as one of the most important and influential female poets in American literature.29

- The Poetry Foundation, “Anne Bradstreet: ‘To My Dear and Loving Husband.’” Poetry Foundation (website), 13 Apr. 2017, www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69434/anne-bradstreet-to-my-dear-and-loving-husband. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 390-391. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 390-391. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 393. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 393. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 390. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 390-391. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 394. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Carrie Galloway Blackstock, “Anne Bradstreet and Performativity,” Early American Literature, vol. 32, no. 3, (1997): 223. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet: ‘To My Dear and Loving Husband,’” The Poetry Foundation, April 13, 2017. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69434/anne-bradstreet-to-my-dear-and-loving-husband. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/anne-bradstreet. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 390. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet: Colonial American Poet,” Literary Ladies Guide, https://www.literaryladiesguide.com/author-biography/anne-bradstreet-colonial-american-poet/. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet: ‘To My Dear and Loving Husband,’” The Poetry Foundation, April 13, 2017. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69434/anne-bradstreet-to-my-dear-and-loving-husband. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/anne-bradstreet. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 406. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 408. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Bethany Reid, “‘Unfit for Light’: Anne Bradstreet’s Monstrous Birth.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 71, no. 4 (1998): 523. https://doi.org/10.2307/366601. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/anne-bradstreet. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/anne-bradstreet. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 394-395. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 394. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Margaret Olofson Thickstun, “Contextualizing Anne Bradstreet’s Literary Remains: Why We Need a New Edition of the Poems,” Early American Literature 52, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 411. https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.2017.0030. ↵

- Bethany Reid, “‘Unfit for Light’: Anne Bradstreet’s Monstrous Birth,” The New England Quarterly, vol. 71, no. 4, (1998): 541-542. https://doi.org/10.2307/366601. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/anne-bradstreet. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet: Colonial American Poet,” Literary Ladies Guide, https://www.literaryladiesguide.com/author-biography/anne-bradstreet-colonial-american-poet/. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet: Colonial American Poet,” Literary Ladies Guide, https://www.literaryladiesguide.com/author-biography/anne-bradstreet-colonial-american-poet/. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet: ‘To My Dear and Loving Husband,’” Poetry Foundation, April 13, 2017. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69434/anne-bradstreet-to-my-dear-and-loving-husband. ↵

- “Anne Bradstreet,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/anne-bradstreet. Accessed 5 Dec. 2024. ↵