In the United States in the 1920s, life was drastically different. Socialism in the United States was growing in popularity, both for American voters and in the media. Eugene V. Debs, a pioneer who paved the way for the Socialist movement in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century faced a challenge that would change the course of America’s history forever, for the better or worse. Debs was on a mission to become the President of the United States, a quest that he had previously attempted four times before, in 1900, 1904, 1908, and 1912, and he also intended to run again in 1920. The pivotal moment in Deb’s career began in the summer of 1918, in the small town of Canton, Ohio, where Debs was speaking at an annual picnic for the American Socialist Party. Here, Debs gathered thousands of supporters and voters to portray his ideals and use his platform to educate others on socialist ideals, as well as speak on injustices that he found important.1

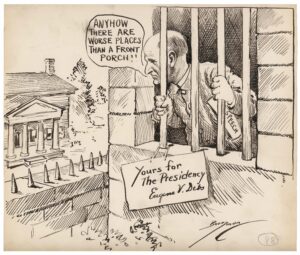

At the annual party picnic in Ohio, Debs felt it important to address his disdain for the war draft and the implications that it had for United States citizens, which was being used at the time to involuntarily enlist young men in the United States to serve in the armed forces during the First World War. He regularly expressed the importance of social reform, and he denounced the war, which included what was arguably his most controversial speech, being delivered in Canton, although this speech was much like many others he gave.2 Debs expressed that he felt there was hypocrisy in how it was “extremely dangerous to exercise the constitutional right of free speech in a country fighting to make democracy safe for the world.”3 He also was sure to mention his disapproval of the Wilson administration’s preparedness program, criticizing the president’s handling of the war.4 He strongly disapproved of the war, stating, “They have always taught and trained you to believe it to be your patriotic duty to go to war and to have yourselves slaughtered at their command. But in all the history of the world you, the people, have never had a voice in declaring war, and strange as it certainly appears, no war by any nation in any age has ever been declared by the people.” 5 This statement and more led to a pivotal halt in Deb’s career. A sedition charge would forever immortalize Debs as the first and only Presidential candidate to run for President from a federal penitentiary to date. Many news outlets portrayed him as a dictator or traitor, despite his many advocates who would regularly gather in the streets in support of him whenever he was close to supporters. The Washington Post was one of many outlets writing scandalous headlines, chronicling “DEBS INVITES ARREST.”6

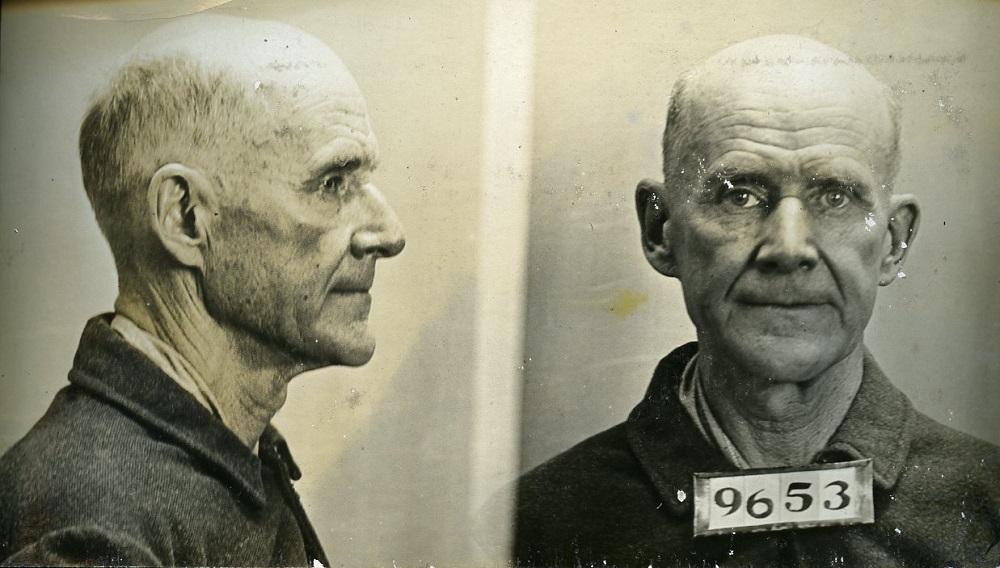

Deb’s trial was quite extensive. It began on September 10, 1918, in Cleveland, Ohio, a mere three months after the famous speech in Ohio. He was charged with sedition under the Espionage Act, which coincidentally was only enacted the previous year.7 Debs chose to go the route of admitting to the crime that he was accused of but argued that the Espionage Act was an attack on the First Amendment, and was therefore unconstitutional. Espionage Act cases were commonly lost at this time, and Debs’ case was no different. There were many accusations brought against him, one of the most serious being that there was reason to believe that draft-age men listened to Deb’s speech against the war draft, and as a consequence, may have shirked their duties to the United States government to serve. However, all men who were cross-examined had done their civic duty and registered, proving this claim to be a weak one, despite the thousands who either had failed to register or deserted in 1918. The trial concluded with one of Deb’s most famous speeches, in which he addressed the jurors to convey his lack of remorse for his act. Although uncommon, Debs insisted that he address the jury personally, saying, “Standing before you, charged as I am with crime, I can yet look the Court in the face…there is festering no accusation of guilt.”8 He also spoke to his claim on the infringement of his First Amendment right, claiming “I believe in free speech, in war as well as in peace.”9 The trial eventually concluded with his defeat and the judge sentencing Debs to three concurrent ten-year sentences in a federal penitentiary, a huge loss for both Debs individually and the American Socialist Party as a whole. He spoke with the fiery passion that he became famous for, claiming that “If the Espionage Law stands, then the Constitution of the United States is dead.”10

In an attempt to appeal his conviction, the Supreme Court ruled that the Espionage Act was to be upheld. In the case Debs v. United States, 249 U.S. 211 (1919), the court held that “his speech was intended to obstruct the war effort.”11 During the time surrounding the First World War, the Supreme Court ruled similarly on several cases regarding the limitation of speech.12 Although he did not believe in the possibility of a successful appeal, Debs was arrested in 1919 and sent to prison briefly in West Virginia before being permanently transferred to the federal institution in Atlanta, Georgia, from where he ran his final presidential campaign.13 Debs was expectedly outspoken about being imprisoned, writing a series of columns about his disdain for the prison system. In one excerpt of his writings from prison, he wrote, “I thank the capitalist masters for putting me here. They know where I belong under their criminal and corrupting system.”14

Debs’ campaign for the presidential race was quite blunt about Deb’s prison sentence and chose to embrace the unprecedented situation rather than shy away from it. Political buttons were regularly distributed, campaign buttons with his convict number on his uniform, capitalizing on his prisoner status and addressing the issue at hand. 15 He also began a campaign called from “Jail House to White House,” which shined his unfortunate situation in a positive light. 16 Although the party was becoming weaker around this time with membership declining, seeing Debs on the ballot despite the bumps in the road was empowering for America’s socialists. Two hundred socialists even traveled to Washington D.C. to pressure the Wilson administration to release Debs, among others. Although this was unsuccessful, there was no doubt that it garnered media coverage for Debs, who was well talked about by the American population at this time, whether he was loved or hated.17

By election night, Debs had amassed 913,664 votes, his second most successful turnout of the five. During and after the election, Debs had been in poor health, both mentally and physically. For starters, he had lost hope for the American population. After five unsuccessful attempts at becoming the first Socialist President of the United States, he lost his last race to a Republican administration that directly conflicted with Debs’ and the American Socialist Party’s views on how the United States should function. He suffered from a heart condition, which often gave him trouble when trying to sleep and go about his daily life while in prison, and was in mental anguish at witnessing and experiencing the atrocities that were committed at the penitentiary in Atlanta. These included seeing a fifth of the prison population perish from syphilis, a botched surgery, and the constant anguish of drug overdoses and fellow inmates in withdrawal. He also experienced multiple loved ones passing or becoming gravely ill while in prison, including his brother. Debs regarded that the conditions were so dangerous and isolating, that the inmates there were experiencing “abysmal depths of depravity that the lower animals do not know.”18

Although President Woodrow Wilson denied a proposition for a presidential pardon for Debs, on December 23, 1921, Debs received the news he had been waiting for. President Harding, who had come to office following Wilson, had decided to commutate his sentence, which the president was sure to differentiate from a pardon. While serving time, he attempted to petition for his release multiple times, getting denied at every turn. It was not until his presidential opponent and future 29th President of the United States, President Harding, commuted the four-time candidate and saw no imminent threat to his seditious acts. Harding was quoted about the situation saying, “There is no question of his guilt. . . . He is an old man, not strong physically. He is a man of much personal charm and impressive personality, which qualifications make him a dangerous man calculated to mislead the unthinking and affording excuse for those with criminal intent.”19 The process was quick and seemingly effortless because Harding released this statement on December 23, and declared that Debs was to be released on Christmas day, just two days following. On that Christmas morning in Atlanta, Georgia, thousands were lined up to celebrate his release from prison. Upon his release to a crowd of fifty thousand who were cheering his name, Debs was invited by President Harding to visit the White House to greet him personally. Harding jokingly told Debs, “Well, I’ve heard so damned much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am now glad to meet you personally.”20

- Melvin I. Urofsky, “Chapter 4: The Trial of Eugene V. Debs, 1918,” Justice and Legal Change on the Shores of Lake Erie : A History of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Paul Finkelman and Roberta Sue Alexander, eds., (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2012), 97-99. ↵

- J. Robert Constantine, “Eugene V. Debs: An American Paradox,” Monthly Labor Review 114, no. 8 (August 1, 1991): 33. ↵

- Eugene Debs’s Speech in Canton, Ohio June 16, 1918, Freedom of Speech : Documents Decoded, 2017. ↵

- J. Robert Constantine, “Eugene V. Debs: An American Paradox,” Monthly Labor Review 114, no. 8 (August 1, 1991): 33. ↵

- Eugene Debs’s Speech in Canton, Ohio June 16, 1918, Freedom of Speech : Documents Decoded, 2017. ↵

- Jill Lepore, “Eugene V. Debs and the Endurance of Socialism,” The New Yorker, accessed January 22, 2024, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/02/18/eugene-v-debs-and-the-endurance-of-socialism ↵

- “Eugene V. Debs,” Britannica, accessed January 22, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Eugene-V-Debs ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010),83-98. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010), 100. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, “Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent,” January 1, 2008, 100-107. ↵

- David Schultz and John R. Vile, The Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties in America (Armonk, N.Y.: Routledge, 2005), 258-260. ↵

- David Schultz and John R. Vile, The Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties in America (Armonk, N.Y.: Routledge, 2005), 258-260. ↵

- Melvin I. Urofsky, “Chapter 4: The Trial of Eugene V. Debs, 1918,” Justice and Legal Change on the Shores of Lake Erie : A History of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Paul Finkelman and Roberta Sue Alexander, eds., (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2012), 112-113. ↵

- “All about Eugene V. Debs, Who Once Fought US Presidential Election from Prison,” Hindustan Times (New Delhi, India), August 26, 2023. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010), 250. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010), 205. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010), 206-207. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010), 257-258. ↵

- Melvin I. Urofsky, “Chapter 4: The Trial of Eugene V. Debs, 1918,” Justice and Legal Change on the Shores of Lake Erie : A History of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Paul Finkelman and Roberta Sue Alexander, eds., (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2012), 115. ↵

- Melvin I. Urofsky, “Chapter 4: The Trial of Eugene V. Debs, 1918,” Justice and Legal Change on the Shores of Lake Erie : A History of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Paul Finkelman and Roberta Sue Alexander, eds., (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2012), 115. ↵

23 comments

Maria Fernanda Guerrero

Great article! I agree with Harding, Debs was indeed an impressive man. I briefly knew Eugene Debs so to know his full story was very interesting. What resonated with me mostly is that despite everyone trying to tire him down, he never stopped advocating and fighting for what he believed in, inspiring many. It’s saddening to hear that our own government punished a man who was only trying to get his voice heard. Thank you for writing this article and bringing awareness to Eugene Debs. Congrats on being nominated!

Madison Hinojosa

I was particularly captivated by this discovery, as it truly intrigued me to learn that individuals can still pursue the presidency regardless of their incarceration status. It was quite compelling to realize that being behind bars does not serve as a hindrance to one’s political aspirations, shedding light on an aspect of the democratic process that is both unconventional and thought-provoking. The fact that individuals in jail can run for the highest office in the country challenges conventional beliefs about eligibility and underscores the complexities of the legal and political systems.

Isaac Fellows

The best historical articles on here are always going to be those that explicitly or implicitly parallel the modern day; this one does that. While Debs never had a chance at winning, what difference would it have made if he had been, still jailed, a former president, and one of the most talked about individuals for the last nine years leading up to election day? I find it interesting how Debs’ imprisonment actually gave him a push, and propelled his campaign. Should we expect the same if Donald Trump were to be convicted before the election?

jhollowell

I personally enjoyed reading this article as I learned about a presidential candidate that I never heard much about. I liked the detailed description of Debs’ speech in Canton, Ohio, as it helped illustrate his eloquent way of speaking and how well he engaged with the audience. I would have liked to learn more about the impact his campaign had in politics in America even though he did not succeed in becoming president.

dandrews2

Hi Jacqueline,

I liked the way you delved into the topic of Eugene V. Debs’ presidential campaign from prison. You do a great job giving a detailed account of Debs campaign, focusing on his anti-war draft speech leading to his imprisonment. Going into his trial and homing in on the defense of free speech was important so it’s great you did that. The paper is well researched utilizing historical facts and quotes. The emphasis of Deb’s commitment to his principles is testament to his legacy and you did an amazing job showing that.

lvaldez12

Hello! I really enjoyed reading this and learning about how Deb’s and his idea as to why he wanted to run for presidency. I also liked how i got to learn that you can still run for presidency even if you are in jail and even though debs was slowly declining in both health and mentally he still kept beliefs.

Walter Goodwin

I’ve only heard of Eugene Debs in reference to his presidential run in 1912, so the chance to read more about him was a very compelling opportunity. The article is extraordinarily well written, I found myself almost cheering at Debs’ release from prison. In the context of so many unjust wars in the last century, his charge of sedition echoes in how many anti-war movements and protesters were met with so much opposition and scorn. However his release echoes how justified those types of movements were in retrospect, especially relating to wars like the Iraq War and Vietnam War. So overall this was an incredible article.

Esmeralda Gomez

I had just learned about this from a class with Dr. Vega! What an interesting coincidence to read and be able to learn more information about something that I was incredibly curious about. Debs seemed to be an inspiring yet legendary person to have been able to accomplish the feats he did. Great job on this article, I truly enjoyed reading it, and I wish you the best on your nomination!

Jonathan Flores

This is a truly interesting and well told story of a man I had never heard of before. I really enjoyed your writing style, and how you chose to structure your ideas chronologically throughout the piece. Overall, I think you did a great job at describing the life of Debs, while highlighting the characteristics of his thoughts that contribute to his unique life. Also, I must say that your title did a great job at hooking me from the choices of many different articles. Nice job.

qmero

You have published a very well-written article! I also appreciate the effort you have put into this article; I’m sure that a topic like yours took a greater amount of research than most others, and I respect your presentation of your hard work. Had it not been for your article, I may have never learned about this prominent figure in American political history. I never knew that America had been influenced by such a prominent socialist figure in the 1920’s.