Ever since it was discovered in 1492, America was surrounded by myths of riches never heard or seen by any man before. It became the source of fantasies for thousands of Europeans who hoped to find in those unexplored lands the new Eden, heaven on earth. Meanwhile, on the continent, the Spaniards, led by their Catholic monarchs, held their fight against the Moro or the Infiel to fulfill their political project of a united peninsula, which also strengthened the Spanish people’s patriotism and faith.1

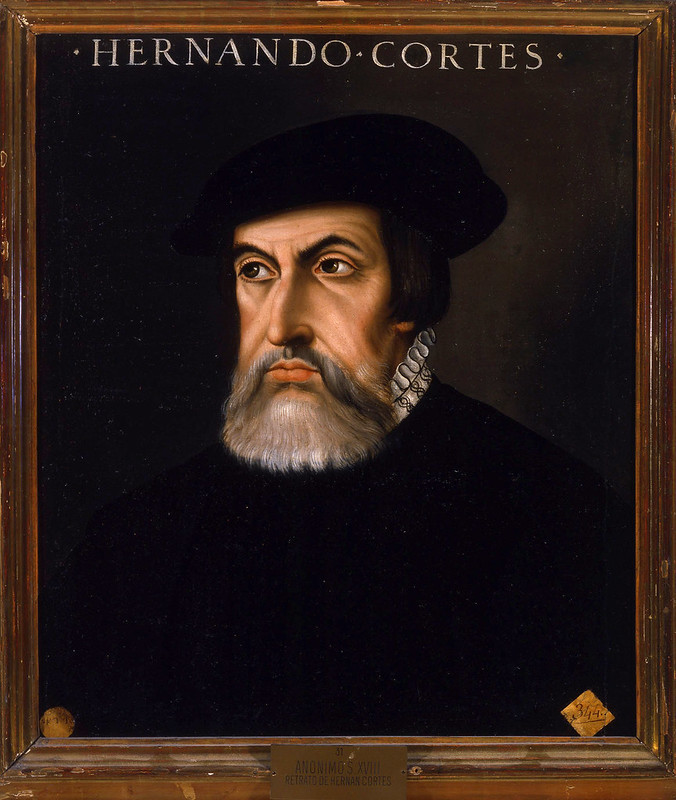

These circumstances, together with the desire to expand Christendom, turned the discovery and conquest of the New World into a new crusade, becoming the perfect cause for a man of that time since serving the crown through participation in this enterprise promised fame, honor, gold, and a place in Heaven, all for those who would dare to uncover its mysteries. Hernan Cortes (1485- 1547) shared these aspirations and was counted among the first conquerors.

Today he is considered a controversial figure. He is famously known for his conquest of Mexico, taking over one of the biggest civilizations in the Americas with less than a thousand soldiers, proving his incredible political and military genius. Even so, all of his accomplishments could have never occurred if in 1518, as he prepared to sail towards the recently discovered lands of Mexico, his dispute with Diego Velazquez, the Governor of Cuba, succeeded in stopping his departure. It was a conflict that risked the very beginning of his whole venture. It contested his loyalty to the Spanish monarchy, and it forever questioned the rightfulness of his authority.

In 1518, General Juan Grijalva returned to Cuba, bringing the riches he traded with the natives on the coasts of Mexico, after a small delay that was enough to fill Governor Velazquez with worries. The governor had already sent a caravel commanded by Cristobal de Olid to find out about their whereabouts, and seeing he also failed to return, he began to prepare a new one, this time to be commanded by Hernan Cortes.2 Yet, Grijalva’s fleet returned to Cuba soon after, in an excellent state, and the impatient Governor was finally relieved. The expedition returned with several pieces of gold, fabrics, and other adornments that quickly attracted the curiosity of their compatriots and increased Diego Velazquez’s desire to rule over those lands, reaffirming his decision to send another expedition.3

Although the initial intention of Cortes’ fleet was to find the location of Grijalva and Olid, and rescue them if necessary, once Grijalva was back without having Cortes sail in his search, he still departed as captain-general and had Grijalva’s ships join his flotilla. His appointment to that position, however, is far from being the product of luck or sympathy. Cortes had managed to gain the support of two important figures who weighed in on the Governor’s final decision: Andres de Duero, who was another one of Velazquez’s secretaries, and Amador de Lares, a royal accountant, who plead in his favor.4 It was, therefore, more likely, a product of his diplomatic maneuvers, especially considering the marked opposition of Velazquez’s household and kinsmen who also wanted the charge and Cortes’ own lack of direct military experience.5

Hernan Cortes’ career so far had relied on his abilities as a man of letters. Thus, aside from the small Indian revolts that happened near his town, he had not participated in any of the expeditions taking place at the time. Regardless of the adventurous desires that made him abandon his law studies at the University of Salamanca and sail towards the new world, once he arrived at Hispaniola in 1504 at nineteen years old, he accepted a piece of land and a position as a public notary in the small town of Azua, where he received an encomiendas of Indians, and settled as a farmer. Cortes had, as his biographer says, “a pleasant life as an amorous gentleman-lawyer-farmer” until 1511, when Diego Velazquez asked him to join his expedition to Cuba, and even then he did so as the King’s treasurer, which meant he would have a civilian charge.6

Nevertheless, picturing Hernan Cortes as a man without ambition or leadership would be far from reality. He quickly became the alcalde of the recently founded town of Baracoa, later named Santiago. In the words of Velazquez himself when he chose Cortez as captain-general, he “knew him to be competent and sagacious and full of courage.”7

All the same, Cortes prepared the expedition enthusiastically and did not hesitate to provide all the necessary funds to finance his fleet, so much so that in the end, he covered most of its expenditure. Nonetheless, his arrangements were not limited to his ships; understanding the effect that appearances had on most people, Cortes made another diplomatic move and took care of, both, the form and the action.8 He made sure to: dress the part, and changed his clothing to a velvet coat covered with gold knots and a plumed hat accompanied by a gold medal, giving “the impression of great wealth and dignity”; to give his expedition a banner to rise under, and for this purpose, he commissioned two standards that displayed the royal arms and a cross accompanied by the following inscription: “Brothers and companions, let us follow the sign of the cross with true faith, and in it, we shall conquer”; and to advertise the rewards of the expedition: gold, silver, and Indians for anyone who would enroll to conquer and settle.9

He now had the appearance of a captain and had presented his expedition as a service to the church and as a campaign to conquer and settle. Cortes and Velazquez both knew that only settling would catch people’s interest, but none of them had the authority to promise such a thing. In doing so though, Cortes compromised the Governor’s word and got from him implicit permission to do so.10

His efforts soon bore fruit, and more than 300 men were soon ready to depart.11 But the numerous recruits were not the only product of Cortes’ actions. Diego Velazquez, who up until then had maintained a friendly relationship with his Captain, saw his worries over a possible betrayal increase day by day, fed by the gossip of his own relatives and his own consciousness. Cortes’ energetic advertisement of the expedition made him start to question the loyalty of his subordinate. The Governor’s distrust, however, was not a sudden product of anxiety, but two factors combined as the reasons for his fears. First, Velazquez had previously found himself involved in an incident with Cortes that nearly cost Cortes his head. In 1509, a group of sisters by the name of Suarez arrived on the island of Cuba, becoming part of the scarce Spanish female residents, and hence, they became very popular. The younger sister, Catalina, caught the attention of Hernan Cortes, who began courting her, apparently, with more success than he had anticipated, as once he grew tired of her graces, he showed no intention to comply with the marriage assurances he had made. It happened that Velasquez’s interest was set on the older sister, María, and so she asked him to intervene in favor of her younger sister’s misfortune. So, he pressured Cortes to fulfill his promise, without much success.12

Moved, perhaps, more by his chief’s attitude over his love affairs than a sense of justice, Cortes decided to meet with a group of conspirators at his house, sometime after. They decided to write down all of their complaints and send Cortes to deliver them to the judges of appeal. He was promptly arrested, and death by the gallows was to be his punishment. Yet, Cortes ran away before Velazquez had decided on his fate, and, after taking refuge inside a church, he went to meet with Catalina, but he was, once again, captured. Even so, he managed to escape his fate one more time, and once he freed himself, he went to Catalina’s house once again and discussed their marriage with her brother. Then he turned up at the Governor’s house and after explaining himself, both slept together in peace. Cortes married Catalina soon afterward.13

The second reason has to do with Velazquez’s intentions with exploring Mexico in the first place, since, in a way, Velazquez was doing exactly what he feared Cortes would attempt to do. He had been sent to the Island of Cuba from Hispaniola by Diego Colon, son of Cristobal Colon and 2nd Admiral of the Indies, 2nd Viceroy of the Indies, and 4th Governor of the Indies. He had the mission of conquering the territory in the admiral’s name; however, Velazquez, wanting to disassociate himself from Diego Colon’s authority, went over his head and sent a chaplain with letters to nobles and priests that could intercede for him in front of the Spanish King Carlos. He asked to get the adelantado of the title of governor of the unexplored lands of Mexico, which meant that he planned to obtain those titles in advance to avoid some other noble taking them from him. But by the time of Cortes’ departure, he had not yet secured the appointment.14

His intentions were reflected in the instructions he gave to Cortes. The document presented clearly that the purposes of the fleet were: to find Grijalva and Olid, as well as another six Spanish captives, to explore the country and collect information about its inhabitants, and to search for gold and silver. 15 However, it remained imprecise about settling, not allowing or prohibiting it. It was a deliberate choice, as it intended to use its vagueness to encourage soldiers to join the expedition without compromising Velázquez. He had not yet received royal authorization to govern those lands, so he could not promise anything about it, still, he was well aware that nothing but settling would catch anybody’s attention. Sadly, for him, the room it left for interpretation, also gave Cortes space to play within, and he, taking the instructions as permission to do what he saw more fit, began promoting his campaign as one to conquer and settle.

Corte’s precautions to use that ambiguity in his favor must also have been due to the way that Velazquez treaded Grijalva. He was sent under similar conditions, and following the governor’s lead, he had only trade, a decision that the governor himself later reproached him for. His obedience did not favor him then nor through history, where he is only to be remembered as the man that, despite having every sign in his favor, failed to see the potential of his advantageous position, and decided to return without even attempting to begin the conquest, a task for which Cortes would later prove to be far more capable.16

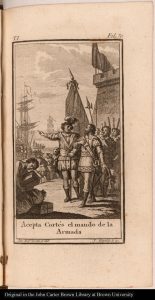

With all of this in mind, Cortes also realized the growing distrust of the Governor, and fearing that Velazquez would retract his appointment as captain, he realized that he might lose his opportunity to lead the expedition. So he tried to stay by the Governor’s side all the time. Yet, Andres de Duero warned him that Velazquez was ready to withdraw his powers. So he sailed prematurely so that the governor would not have time to revoke his authority. Hence he parted towards the port of Trinidad at dawn on November 18, 1518, where he was to finish replenishing his provisions. But this was was the straw that broke the camel’s back, and the Governor decided that it was time to stop Cortes. He sent letters to his brother-in-law, Francisco Verdugo, who was the magistrate of Trinidad, saying that Cortes was no longer to command the fleet and that he should be stopped. But seeing the number of men that Cortes carried with him and their utmost eagerness and loyalty to Cortes, Verdugo did not dare to do so. Velazquez was outraged, but he wouldn’t give up so easily, so he sent his servant, Gaspar de Garnica, to Cortes’ next stop, la Habana, with orders to contain the armada and arrest Cortes. Yet, once more, nobody attempted to follow the Governor’s orders, and so Cortes sent a reply telling Velazquez that he was about to sail and that he promised to serve his majesty the King.17

Those were the conditions in which Cortes embarked unknowingly toward one of the greatest episodes of the Conquest of the New World. He knew the possible consequence that his actions could carry was death, for him and his soldiers, but they knew the risks well, and none of them tried to back out.

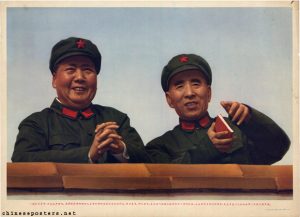

- Featured image is an Oil portrait of Hernan Cortes by an Unknown painter, XVII century | Courtesy of Museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. Madrid. ↵

- John F. Schwaller, and Helen Nader, The First Letter From New Spain : The Lost Petition of Cortés and His Company, June 20, 1519 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014), 11-12. ↵

- Lopez de Gomara, Francisco, La Conquista de Mexico / Francisco Lopez de Gomara (Editorial Linkgua, 2011), 25-29. ↵

- Bernal Diaz del Castillo, Historia Verdadera de La Conquista de La Nueva España / Bernal Diaz Del Castillo; Introducción y Notas Por Joaquín Ramírez Cabañas (Espasa-Calpe Mexicana, 1950), 104. ↵

- Francis L Hawks, (Francis Lister), The Adventures of Hernan Cortes … By the Author of ‘Uncle Philip’s Conversations.’ Making of America (MOA), n.d, 23-25. ↵

- Salvador de Madariaga, Hernan Cortes, Conqueror of Mexico (Florida: University of Miami Press, 1967), 55-59. ↵

- Henry Morton Robinson, Stout Cortez: A Biography of the Spanish Conquest (The Century Co., 1931), 28-29. ↵

- Salvador de Madariaga, Hernan Cortes, Conqueror of Mexico (Florida: University of Miami Press, 1967), 96-97. ↵

- Bernal Diaz del Castillo, Historia Verdadera de La Conquista de La Nueva España / Bernal Diaz Del Castillo; Introducción y Notas Por Joaquín Ramírez Cabañas (Espasa-Calpe Mexicana, 1950), 106-107. ↵

- Salvador de Madariaga, Hernan Cortes, Conqueror of Mexico (Florida: University of Miami Press, 1967), 96-97. ↵

- Henry Morton Robinson, Stout Cortez: A Biography of the Spanish Conquest (The Century Co., 1931), 32-33. ↵

- Francisco Lopez de Gomara, La Conquista de Mexico / Francisco Lopez de Gomara (Editorial Linkgua, 2011), 19-20. ↵

- Salvador de Madariaga, Hernan Cortes, Conqueror of Mexico (Florida: University of Miami Press, 1967), 62-67. ↵

- Salvador de Madariaga, Hernan Cortes, Conqueror of Mexico (Florida: University of Miami Press, 1967), 68-69, 88-89. ↵

- José Luis Martínez, Documentos cortesianos I: 1518-1528. Secciones I a III. México (D.F.: FCE – Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2016), 46-49. ↵

- Henry Morton Robinson, Stout Cortez: A Biography of the Spanish Conquest (The Century Co., 1931), 25-27. ↵

- Bernal Diaz del Castillo, Historia Verdadera de La Conquista de La Nueva España / Bernal Diaz Del Castillo; Introducción y Notas Por Joaquín Ramírez Cabañas (Espasa-Calpe Mexicana, 1950), 111-120. ↵

11 comments

Michaell Alonzo

Hey Kelly, congrats on being nominated for an article award. This post was so beautifully written and fascinating to read. This page has an astonishing quantity of specific information. I believe that understanding people’s levels of authority is crucial. This essay truly caught my attention because it explores Cortes’ life narrative and the struggles he faces. I really adored the pictures you chose, which perfectly complemented the narrative you were presenting. I really appreciated how well-organized you were; it made the reading interesting for me.

Adriana Chontal

Estimada Kelly;

Su artículo sinduda logro captar mi atención, me permitió conocer sobre este personaje puntos que no había analizado antes. Es gratificante ver trabajos que permitan al lector desarrollar el interés. FELICITACIONES

Jose Luis Gamez, III

Great article and images Kelly. I enjoyed your detailed research on Cortes. I took another angle regarding Cortes’ leadership during the Conquest in the New World. The conflict emerges when the Governor tried to overrule Cortes’ authority as civilization and government was further established in the New World. Cortes was loyal to the King.

Kayla Braxton-Young

I haven’t really learned about this topic, but reading the article was very interesting and I learned a lot, just by reading this article. I feel like it is extremely important to learn about the authority that people have. This article focuses on Cortes and his journey. I really found this article interesting because it unpacks the story of Cortes and what he goes through in life.

Evelyn

Kelly, me encantó leer tu artículo.

Joshua Marroquin

I would first like to congratulate the author for a well written article that got published and nominated.Despite being initially praised by the Spanish Crown, Cortés soon found himself outnumbered by a new generation of colonial administrators and engaged in ongoing legal disputes where he was accused of abusing his power, taking more loot than was due, and committing atrocities against indigenous peoples.

Francisco Caballero

Great article, I find it interesting to read about the beginning of his journey, it’s pretty crazy that all of his crew knew about the risks yet none of them backed out. This was an impactful part of history and its interesting to read about how it played out.

Ana Barrientos

I enjoyed reading your article, it is very detailed, and I liked how the story flowed. I also liked your images, but what I found interesting was that Cortes escaped twice from his fate. Cortes seemed to like being in control and going on expeditions, another thing I found interesting was that the governor kept sending orders to stop Cortes, but nobody did them. Overall, great job!

Robert Miller

Excellently written article Kelly! I never thought about the exploration of the New World being considered as a kind of “crusade”, but it makes sense. Cortes was actually a good leader and his people stuck with him. Great read!

David

Great topic, Kelly.

Although they didn’t realize it, they were at the beginning of a new era.

If the Hollywood producers would know these stories, I’m sure they’d make amazing films inspired in these actual events.