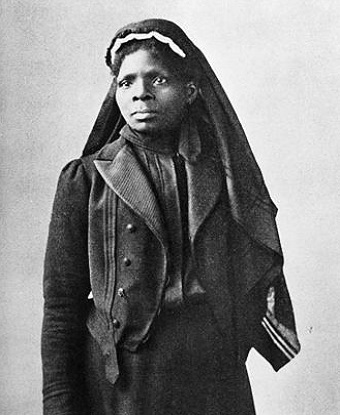

The air along the Georgia coast in 1863 was filled with heat, salt, and the smell of wounded soldiers. Canvas tents were placed close together in muddy rows full of wounded men from the Civil War. Inside one of these tents stood a young woman, Susie Baker King Taylor. She moved from bed to bed, busy trying to wash bloody bandages and comfort frightened soldiers.

Baker had been born into slavery in Savannah, Georgia, in 1848. As a little girl, she was secretly taught how to read and write, which was against the law for enslaved people.1 She learned in secret, but this secret was the one that later on helped her to change and save lives.

When the Union Army captured parts of the coast, Baker took the opportunity and escaped to freedom. There she joined the first South Carolina volunteers, who were the first regiment of Black soldiers from the South to fight for the Union.2 Baker worked as a nurse and teacher, which were roles that very few women, especially black women, were allowed to have at that time.

Even during her service of being a nurse and a teacher, racism followed. White officers doubted her and her capabilities to do her duties. One muttered that she was too delicate to handle blood. Others looked at her with doubt and disbelief, wondering why she would risk her life for soldiers who didn’t believe in equality.3

Even though she faced all these challenges, Baker didn’t let their judgment stop her. She focused on her work, which consisted of endless cleaning and healing of wounds, and comforting those who had given their all for freedom. She knew that her contributions were a way to show that black people were just as capable and worthy as anyone else.

On a stormy night, the war came closer. Word went around the camp that there had been a fierce fight. Gunfire echoed in the distance, and soon after, rowboats filled with wounded men arrived at the camp. Some were bleeding uncontrollably, others were shaking due to their high fevers, and all were filled with fear. Inside their tents, there was a whole lot of chaos. Supplies ran low, there were no clean bandages, and not enough medicine. The doctors and nurses, including Baker, worked quickly, but it was still not fast enough. Many doctors prioritized white soldiers first, leaving black soldiers to wait. Baker noticed everything that went on inside those tents; she was filled with anger and disappointment.4

“They’re brave enough,” one officer said, watching wounded black men being brought in. “But they’ll never be equal.” Baker didn’t respond to his statement, but his words altered something in her. Instead of arguing, she got back to work, faster and harder. She boiled water, tore clean strips from the sheets, and used herbs the way she had learned from her grandmother. She pressed cloths to contain the bleeding from the wounds and comforted the soldiers, whispering to them that everything would be all right.5

Her nursing knowledge came from the teaching her grandma had taught her as a young girl, as well as her front-line experience during the Civil War. She never had formal training. She learned to make do with what she had and her grandmother’s teachings.

Later, she wrote, “It is sad to think that after all the service rendered by the colored soldiers, prejudice should still linger. But I have learned that goodness and knowledge are the true weapons of equality.6 That night, Baker became more than just a nurse; she was the light of strength for those around her. 7

Just before dawn, another group of wounded soldiers from the battlefield came in. Most of them arrived in very critical conditions. Most doctors would have nothing left to do, but Baker refused to give up on the wounded men. She grabbed clean rags, boiled water over the fire, and cleaned some of the worst wounds herself. She would whisper prayers as she worked. Her hands stayed steady even as her tiredness tried to get the best of her. A doctor stopped and looked over at Baker. He then silently joined her in her efforts. She worked all night long, when dawn came, several men who had no hope of surviving were still breathing. Her persistence and efforts made the difference.8

When the sun rose, the camp sat in silence. There was no rain, and the smell of gunpowder still remained in the air. Baker stepped outside, and from behind her, one of the wounded men thanked her quietly. Others did as well with nods. They called her “Miss Susie” instead of “girl” or “colored woman,” which for her carried more weight than any reward ever would. In that moment, Baker felt seen for who she truly was, a nurse and teacher who did her duties with pride.9

Later on that day, Baker sat near a campfire with her journal in her lap. She wrote about her experience serving to help wounded soldiers during the Civil War and her endless work. She wrote in order for others to maybe someday understand what black soldiers and nurses had to go through. “I gave my service willingly,” she recalled later on, “for I felt it was my duty to help those who offered their lives for liberty.”10

The war continued, and so did Baker. She kept doing her duty as a nurse and teacher, and helped as a South Carolina Volunteer until the group scattered. Her courage and commitment were the living proof that black women were not just witnesses of history, but they were also capable of making history.11

Susie Baker King Taylor’s story is one of the silent bravery that people of color had to endure. She didn’t fight with guns, but she fought against racism and fear. As one of the first black nurses in the Union army during the Civil War, she showed the world how strength and compassion can stand side by side.

Years later, she published her experience in Reminiscence of My Life in Camp. In it, she described the horrors of the war and also the challenges she faced for being a black woman among white officers. “We were loyal,” she wrote, “and tried to do our duty faithfully, for we were anxious for the success of the Union.”12

Her writing showed the courage it took to survive on the battlefield and weather the prejudice that surrounded her. Her story is a clear reminder that heroism isn’t always loud; it can be quiet and steady. The Georgia Historical Society now honors her as a nurse, teacher, and pioneer who opened the doors for generations to come. 13

- Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, with Internet Archive (1968), http://archive.org/details/reminiscencesofm0000susi. ↵

- Anders Bradley, “The First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment (1862-1866),” BlackPast.Org, September 9, 2018, https://blackpast.org/african-american-history/first-south-carolina-volunteer-infantry-regiment-1862-1866/. ↵

- Cassidy McNeeley and Reporter Correspondent, “FORGOTTEN NO MORE: Uncovering the Remarkable Story of Civil War Veteran Susie King Taylor | Dorchester Reporter,” accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.dotnews.com/2024/forgotten-no-more-uncovering-remarkable-story-civil-war-veteran-susie. ↵

- Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, with Internet Archive (1968), http://archive.org/details/reminiscencesofm0000susi. ↵

- Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, with Internet Archive (1968), http://archive.org/details/reminiscencesofm0000susi. ↵

- Cassidy McNeeley and Reporter Correspondent, “FORGOTTEN NO MORE: Uncovering the Remarkable Story of Civil War Veteran Susie King Taylor , 42| Dorchester Reporter,” accessed October 27, 2025, https://www.dotnews.com/2024/forgotten-no-more-uncovering-remarkable-story-civil-war-veteran-susie. ↵

- “Susie King Taylor (1848-1912) – Georgia Historical Society,” https://Www.Georgiahistory.Com/, n.d., accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.georgiahistory.com/ghmi_marker_updated/susie-king-taylor-1848-1912/. ↵

- Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, 48-49, with Internet Archive (1968), http://archive.org/details/reminiscencesofm0000susi. ↵

- Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, 50-51, with Internet Archive (1968), http://archive.org/details/reminiscencesofm0000susi. ↵

- Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, 53, with Internet Archive (1968), http://archive.org/details/reminiscencesofm0000susi. ↵

- “Susie King Taylor Assists the First South Carolina Volunteers, 1862-1864,” accessed October 20, 2025, https://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6599/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. ↵

- Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, 72, with Internet Archive (1968), http://archive.org/details/reminiscencesofm0000susi. ↵

- “Susie King Taylor (1848-1912) – Georgia Historical Society,” https://Www.Georgiahistory.Com/, n.d., accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.georgiahistory.com/ghmi_marker_updated/susie-king-taylor-1848-1912/. ↵